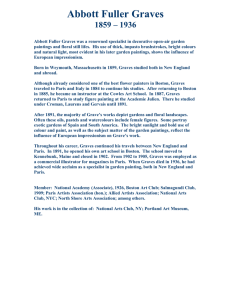

Robert Graves

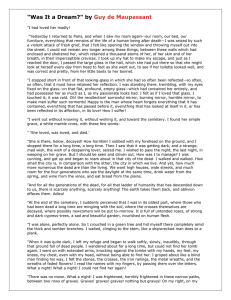

advertisement

Link 31 In his memoir Good-Bye To All That, Robert Graves wrote of his injuries in World War 1, among them what was then called shell-shock or war neurosis. Although he indicates the cause as his being wounded at the Battle of the Somme, his description of his battlefield experiences indicates the beginning of his debility almost as soon as he entered battle. Under his first bombardment, the concussion of the shelling knocked him to his knees; he was unable to stand, and his head and body were tingling. Obviously, he was subject to a great many such bombardments. One can only guess at the effects of the days of twenty-four hour bombardments on the German lines on those soldiers. I discuss the lifelong effect of Graves’s post traumatic stress disorder in my book The Early Poetry of Robert Graves. Before the war, Graves was quite representative of the educated and privileged class. During the war, he lost confidence in a reality that was reasonable and predictable, lost belief in his ability to direct his own existence. Instead of these becoming debilitating, they became essential to his understanding of himself as poet, a being subject to the desires and will of a muse who was herself an emissary of a divinity he called the White Goddess. He found delight in his role, and the rest is literary history. Of the lingering difficulties of his injury, two stand out for me. He had been shocked by a trench telephone. When I was in Deya de Mallorca in 1969 to visit with him, I asked his son William if I should telephone the house before visiting. William told me just to go there because Robert wouldn’t have a telephone in the house. The other lingering effect was train travel. After being wounded at the Somme, he had been left for dead (actually reported to his parents as dead). When he was found to be alive, his wounds were dressed and he put on a stretcher and taken by train to a hospital. He was on that stretcher for five days. He simply described the experience, especially the train trip, as nightmarish. Some of us may have such nightmarish experiences. And even those of who haven’t , have lesser experiences that allow a sympathetic understanding. I remember the after effect of having my vehicle hit broadside by a speeding car. For many months after, I had to control my urge to steer abruptly to the left when a vehicle pulled close to me on the right. Sadly, our military in Iraq and Afganistan are as subject to post traumatic stress disorder as any in the history of warfare, and our daily news recounts their travail. As a veteran of the war in Viet Nam told me, these wars are different from his in Viet Nam. There bullets went in and came out. He only once had to collect the body parts of a comrade. Such deaths are commonplace in the contemporary wars because roadside bombs, IEDs, which figure so prominently in the wars.