I rapporti tra Anselmo di Canterbury e la contessa

advertisement

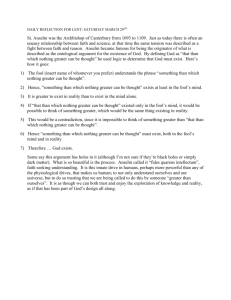

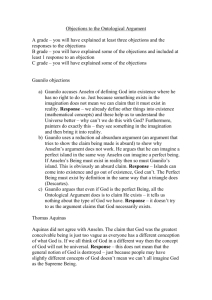

1 Paolo Golinelli “Non semel tantum sed pluribus vicibus”. The Relations between Anselm of Canterbury and Mathilda of Tuscany The relations between Anselm of Canterbury and Countess Mathilda of Tuscany/Canossa have generally been neglected in historiography. Anselm’s biographers, relying on Eadmer, have confined themselves to the recollection of the support granted by the Countess to Anselm during his voyage from Rome to Lyon at the end of the year 1103; 1 scholars of Mathilda have often quoted (and reported) the letter in which Anselm expresses his gratitude to Mathilda, especially to underline the advice that the prelate gave to the Countess to wear a nun’s habit when she’d take to her deathbed. 2 Actually, these are the sources, besides a letter by Mathilda to Pope Paschal II, dated between the end of 1104 and the beginning of 1105, in which she invites him to intervene in favour of the Cantabrigian holy man, correctly edited in the Urkunden und Briefe of the Countess by Elke and Werner Goez,3 and, more interesting, the gift of the book of the Orationes seu meditations, according to a particular version defined as “Second” or “Mathildan”. This work has been handed down to us in a number of different illuminated manuscripts; of which the most important is certainly the splendid codex 289 of the Stiftsbibliothek of Admont, derived from an archetype from which two other two manuscripts have been copied during the XIIth century in England: the ms. * Paper read at the International Congress on “Saint Anselm and His Legacy”, organized by the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies (Durham University) in Canterbury, April 22- 25, 2009. 1 R. W. SOUTHERN, St. Anselm: a Portrait in a Landscape, Cambridge 1990 (Italian.translation: Anselmo d’Aosta. Ritratto su sfondo, ed. by I. BIFFI e C. MARABELLI, Milano 1998, p. 171); SALLY D. VAUGHN, St Anselm and the Handmeindens of God: a Study of Anselm’s Correspondance with Women, Turnhout 2002; I. BIFFI, Anselmo d’Aosta e dintorni, Milano 2007, p. 199. 2 A. MERCATI, Frammenti matildici, II. Matilde e S. Anselmo di Canterbury, in ID., Saggi di storia e di letteratura, Roma 1951, pp. 19-22; P. A. MACCARINI, Diplomazia autonoma di Matilde di Canossa, in In memoria di Leone Tondelli, ed. by N. Artioli, Reggio E. 1980, pp. 251-266; A. PETRUCCI – E. BAMBINO, Anselmo d'Aosta e Matilde di Canossa, in «Reggio Storia», 21 (July-Sept., 1983), pp. 18-22; PIER ANDREA MACCARINI, Anselme de Canterbury et Mathilda de Canossa dans le cadre de l’influence bénédictine au tournant des XIe et XIIe siècles, in Les mutations socio-culturelles au tournant des XIe et XIIe siècles : Etudes anselmiennes, sous la dir. de R. FOREVILLE, Paris 1984, pp. 331-40 (Spicilegium Beccense, 2); P. GOLINELLI, Matilde e i Canossa, Milano 2004. 3 E. GOEZ and W. GOEZ, Die Urkunden und Briefe der Maekgräfin Mathilde von Tuszien, in M.G.H., Laienfürsten-und Dynastenurkunden der Kaiserzeit, II, Hannover 1998, n. 84, pp. 241-242. 2 Auct. D.2.6 of the Bodleian Library, belonging to the nearby nunnery of Littlemore, and the cod. 70 of the Bibliothèque Municipale of Verdun, belonging to St. Albans4. Relevant research by di D. M. Shepard5 has led to the identification of the abbess Diemud who appears in the miniature of f. 44v with the ruler of the monastery of Nonnberg in Salzburg between 1117 and 1139. This allows us to anticipate the date of the manuscript, that Pächt had established around 11606, to a time much nearer to the composition of the original text destined for the Countess Mathilda. As for its material realization, Giusi Zanichelli7, following other scholars8, assumes that it was the work of an Italian scriptorium, where at least the first miniatures had been completed. In Mathilda’s portrait, in fact, she identifies relevant similarities with other miniatures that represent the Countess, such as ms. O.II.11 of the Biblioteca Capitolare of Modena. In her article she also states that it would have been hardly possible for the exiled Anselm to avail himself of such a sophisticated laboratory capable to produce such a refined manuscript. Chiara Frugoni has seen in Mathilda’s gesture not the act of someone receiving the gift of a book, but the act of someone donating a book to an enthroned character, which reminds her of a famous image of the Abbot Desiderius of Montecassino caught in the act of donating a book to St. Benedict, where the position of the hands seems to be the same9. From this reasoning it follows that Mathilda, after receiving a copy of the text, had it reproduced in one of the scriptoria of her monasteries – perhaps in Tuscany, or maybe in San Benedetto Polirone, near Mantua –, and decorated with miniatures as well as a magnificent cover embedded with precious stones, before returning it to its author. O. PÄCHT, The Illustrations of St. Anselm’s Prayers and Meditations, in «Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes», 19 (1956), pp. 68-83. 5 D. M. SHEPARD, Conventual Use of the St. Anselm’s Prayers and Meditations, in «Rutgers Art Review», IX (1988), pp. 1-16. 6 PÄCHT, The Illustrations of St. Anselm’s Prayers and Meditations, cit., p. 71. 7 G. ZANICHELLI, n. 18 , in L’abbazia di Matilde. Arte e storia in un grande monastero dell’Europa benedettina [San Benedetto Po 1007-2007], ed. by P. GOLINELLI, Bologna 2008, pp. 112-113. 8 In particular A. WILMART, Le recueil de prières aderessé par saint Anselme à la comtesse Mathilde, in «Revue Bénédictine», XLI (1929), pp. 35-45, pp. 38-40 (re-printed in ID., Auteurs spirituels et textes dévots du Moyen Age latin. Études d’Histoire Littéraire, Paris 1932; Réimpression, Paris 1971, pp. 162-172, to pp. 165-167). 9 C. FRUGONI, Per la gloria di Matilde: il contributo delle immagini. Le miniature medievali, in I mille volti di Matilde. Immagini di un mito nei secoli, ed. by P. GOLINELLI, Milano 2003, pp. 53-54. 4 3 If it is true – as Donizo states10 – that Mathilda loved books and that within her cenobii there were a few, important, active scriptoria, then, it seems to me that there’s no need to reach the conclusion of a reversal of roles, transforming the person who gives into the one who receives. First of all, normally, it is the author who donates the book he has written (consider the original manuscript by Donizo with its initial miniature); secondly, the posture of the figures in the miniature does not represent the action, but the social position of the characters portrayed; thirdly it was not at all impossibile for Anselm to have a precious copy made at Lyon, where he went immediately after leaving the territories of Mathilda, or at Cluny, or at Canterbury, if the work belongs to the time of his return to England, as Southern has convincingly argued 11. To all these reasons we can also add the prominence granted to Mathilda in the Admont manuscript, which is supposed to be the best copy of the original which was donated. Her standing figure towers above the archbishop seated in his cathedra, at the beginning of the manuscript, and she is represented parallel to the one of Anselm in Mandorla, depicted at the end of the dedication letter on the verso of f. 212; and these same images are reproduced in the manuscript of Littlemore. “For Mathilda to take up a book like Admont MS 289 was the action of a powerful and wealthy lord”, Rachel Fulton states13. The gift is documented in the letter Anselm sent to Mathilda. The holy man, who had learnt from one of his closest collaborators, the monk from Christ Church (Oxford), Alexander14, that Mathilda did not own the Book of Prayers and Meditations, promised to send her a copy, as a token of his gratitude for what she had done to free him “non semel tantum, sed pluribus vicibus”, from the hands of those enemies who wanted to ensnare him, as well as for the goodness and motherly affection she had shown him15. This corresponds perfectly with the opening letter of the Manuscript “Copia librorum non defuit huicve bonorum / Libros ex cunctis habet artibus atque figuris”: Vita Mathildis, II, vv. 1370-71, in DONIZONE, Vita di Matilde di Canossa, ed. by di P. GOLINELLI, Milano 2008, p. 226. 11 SOUTHERN, St. Anselm: a Portrait in a Landscape – Italian translation: Anselmo d’Aosta. Ritratto su sfondo, Milano 1998, p. 117. 12 PÄCHT, The Illustrations of St. Anselm’s Prayers and Meditations, cit., p. 73. 13 R. FULTON, Praying with Anselm at Admont: A Meditation on Practice, in «Speculum», LXXXI (2006), pp. 700-733, a p. 722. 14 SOUTHERN, Anselmo, cit., pp. 257-258. 15 ANSELMI, Epistolae, n. 325 (IV, 37), ed. F. S. SCHMITT, S. Anselmi Cantauriensis Archiepiscopi Opera Omnia, V, Edimburgi 1961, pp. 256-257. 10 4 of Admont which reads: “Anselmus indignus Cantauriesis ecclesiae episcopus reverendae comitissae Mathildae salutem. Placuit celsitudini vestrae ut Orationes quas diversis fratribus secundum singulorum peticionem mitterem edidi” 16. In the Admont ms. mitterem ends the recto of f. 2 and edidi begins the verso of the same sheet, as if the amanuensis had let his pen guide him, anticipating the action of sending the prayers even before composing them. Therefore, there is a specular congruity between the miniature of the gift of the book by the enthroned archbishop with the dedication letter, that adapts for the occasion a previous version of the dedication, in which Mathilda did not appear. From the dedication it seems as if the manuscript were a collage of prayers and meditations composed on purpose for the Countess; however, the inclusion of texts that have little bearing with her world, and the lack of even one single, specific, prayer for Mathilda17, leads us to conjecture that the collection had been previously compiled for a different destination18. Then it was used with a new objective in mind by adding two sheets (binio), at the beginning of the lost archetype, with the miniatures and the letter of dedication. This is the reason why Anselm formulates a sort of apology regarding the unsuitable content of some of the meditations when he addresses the Countess – “quamvis quaedam sint quae ad vestram personam non pertinent” –, in which Marabelli has recognized the reference to the Deploratio virginitatis amissae19. This reference would strike a false note to the ear of Mathilda of Canossa, forced, as she was by fate, to marry twice, to undergo the “mala gaudia carnis”, as the bishop of Lucca Rangerio reported20, and to give birth to a little girl who died prematurely21, when her only and most intimate desire was to dedicate herself to the monastic life. Mathilda spoke about such events to Anselm many times, ANSELMO D’AOSTA, Orazioni e meditazioni, ed. by I. BIFFI e C. MARABELLI, Milano 1997, pp. 120-121. J.-F. COTTIER, Anima mea: prières privées et textes de dévotion du Moyen Âge latin, Turnhout 2001, p. lxxi, n. 169; FULTON, Praying with Anselm at Admont, cit., p. 712. 18 Cottier argued that it was the personal copy of Anselm: COTTIER, Anima mea, cit., p. LXXXIX. 19 ANSELMO D’AOSTA, Orazioni e meditazioni, cit., p. 120, note 2. 20 RANGERIO, Vita Metrica S. Anselmi Lucensis episcopi, ed. E. SACKUR - G. SCHWARTZ - B. SCHMEIDLER, in M.G.H., Scriptores, XXX, 2, vv. 3572-3577, p. 1232. 21 Mathilda had a daughter called Beatrice from her first husband Geoffrey the Hunchback, who died while still an infant on January 29 1071: P. GOLINELLI, Modena 1106: istantanee dal Medioevo, in Romanica. Arte e liturgia nelle terre di San Geminiano e Matilde di Canossa, Modena 2006, pp. 14-15. 16 17 5 because he probably stayed in her company much longer than the sources state, at least from what we gather from the letter that Anselm wrote to the Countess: “Sancti desiderii vestri in corde meo semper servo memoriam, quo ad contemptum mundi cor vestrum anhelat, sed illud sancta et necessaria, quam erga matrem Ecclesiam habetis, pie dilectio retractat” and he reccommends that she’d vow herself to God when death approached her and that she’d keep, always and secretly with her, a veil that she was to wear on her deathbed. Gregory VII’s reaction was completely different in the year 1074 when he had denied Mathilda even the possibility of dedicating herself to a religious life, because he needed her help22. But Anselm who, not without difficulty, had left the monastic life in favour of the bishophood 23 , was the one who could better understand the aspirations of the Countess. The relationship between Anselm and Mathilda is defined on two levels: spiritual because as a counsellor, he brought comfort to the Countess in the last period of her life when her religious vocation became more urgent, and political because he received great support from Mathilda at the time of his trouble with the English monarch. From this derives the precious gift and the letter of gratitude, because “non semel tantum, sed pluribus vicibus me Deus per vos liberavit de potestate inimicorum meorum expectantium ut in manus eorum caderem”, and, in exchange, also her kind behaviour and hospitality: “quam benigno, quam pio, quam materno affectu”. The expression “non semel” (not only once) leads us to believe that Mathilda offered her protection to Anselm during his voyage to Rome in 1103, which is documented by Eadmer, but also during the previous period of exile which began in October 1097. From what the sources narrate Anselm seems to be constantly on the move, first in France, at St. Omer, Cluny, Lyon, then, during the Easter of 1098 (March 28), at San Michele della Chiusa, then in Rome and, afterwards, in Southern Italy, and, in October, in Bari, for the Council. At Christmas time he’s in Rome, where he stays for the Council from April 25 to May 1. He then leaves for Lyon, taking the via Francigena and passing 22 GREGORIO VII, Registrum, ed. E. CASPAR, in M.G.H., Epistolae Selectae, Berlin 1920, I, 47, p. 71; for which see P. A. MACCARINI, Aspetti della religiosità di Matilde di Canossa, in Reggiolo Medievale, Reggio E. 1979, pp. 53-66, in particular, pp. 57-58. 23 S. N. VAUGHN, Anselm: Saint and Statesman, in «Albion», 20, 2 (Summer, 1988), pp. 205-220, especially, p. 207. 6 through Piacenza24. For most of his itinerary, from Latium, to Tuscany, to the Parma Appennines and also to part of the Po Valley, the road ran through the territories of Countess Mathilda. Therefore it was impossible to go from France to Rome without being escorted by her troops or by the protection of her vassals. Although in that particular moment of the investiture struggle, with the anti-Pope Clement III, the presence of the troops of Henry IV and the betrayal of the towns as well as of some of Mathilda’s castles, the journey could be particularly dangerous for anyone who sided with Urban II who had supported the reform of the Church, established by Gregory VII. Anselm, although rather late – since he had accepted the investiture as archbishop of Canterbury from the King of England, William II Rufus, -- perhaps more as an acknowledged tradition, than for having been informed about the new papal dispositions, (as Biffi suggests) — had sided with the Reform, “exporting” the issue on the other side of the Channel, and claiming the right to libertas for his church in Canterbury. These developments in his personal maturity were favoured by his relationship with the archbishop of Lyon, Hugo from Die25, one of the leaders of the most inflexible party of the Gregorian reform. At the time of his death (1085), Gregory VII, had included him among his three possible successors, along with Oddo from Ostia (then Urban II) and Anselm from Lucca, but he was unable to reach Rome in time for the conclave (and Hugo complained for this in two letters sent to Mathilda). At the end, after a year of interregnum, the winner was the Abbot of Montecassino, Desiderius (Victor III), who was followed by Urban II, both in favour of an agreement without struggle with the Emperor and the various European rulers26. Urban II distinguished himself for a tendency to compromise even with the English King, raising some misgivings also in Anselm of Canterbury. What takes place then is the formation of another inflexible course of action against political interferences in episcopal elections, composed by Hugo 24 EADMER, The Life of St. Anselm Archbishop of Canterbury, ed. R. W. SOUTHERN, Oxford 1972, p. 87, n. 2. F. S. SCHMITT, Anselmo d’Aosta, santo, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 3, Roma 1961, pp. 387-399, underlines the existing bonds between Anselm and Hugo from Die. 26 P. GOLINELLI, Sulla successione a Gregorio VII: Matilde di Canossa e la sconfitta del riformismo intransigente, in A Ovidio Capitani. Scritti degli allievi bolognesi, ed. by M. C. DE MATTEIS, Bologna 1990, pp. 67-86. 25 7 of Lyon, the Countess Mathilda of Canossa and Anselm of Canterbury who went in substitution of the bishop from Lucca by the same name who had died27. Mathilda was at the centre of the struggle and supplied it with economic and military support and shelter for those prelates who had become its victims. Elke Goez in a short paper on the “guests” of Mathilda28 lists a few names, starting with Anselm of Canterbury. Personally, I think that many were really refugees who received protection from the Countess: Anselm of Lucca was certainly one of these, thrown out of his see by the canons to whom he wished to impose canonical life; another was the Abbot of San Benedetto Polirone, when Henry IV conquered Mantua; another was Conrad, archbishop of Salzburg, forced to flee from his see because openly in contrast with the Emperor Henry V in 1111; also Gebehard bishop of Constance, whose see was returned to him by Mathilda of Canossa29; and, for some time, also Anselm of Canterbury. His most documented stay with Mathilda is, of course, the one at the end of 1103, together with Eadmer. Anselm’s biographer narrates – not in the Vita Anselmi Cantauriensis but in the Historia Novorum in Anglia30 – how she accompanied him from Rome across the Appennines “per Alpes” up to Piacenza. Leaving on November 16, Anselm stayed a night in Florence31, then with Mathilda’s guards he continued his trip along the via Francigena; he stopped in Piacenza, finding shelter, perhaps, by the nuns of San Sisto, and then he continued slowly until he arrived at Lyon in January. There was ample time, over a month, to intensify relations with Mathilda of Canossa, to learn about her strategic ability, the travails of her unfortunate soul, forced, because of the choices 27 H. E. J. COWDREY, The Gregorian Riform in the Anglo-Norman Lands and in Scandinavia, in Studi Gregoriani, XIII (Roma 1989), pp. 321-352, at p. 349: “as archbishop of Canterbury Anselm insisted more stringently than Lanfranc upon contact with Rome and obedience to its decrees”. 28 E. GOEZ, Matilde di Canossa e i suoi ospiti, in I poteri dei Canossa. Da Reggio Emilia all'Europa. Atti del convegno internazionale di studi (Reggio E. - Carpineti, October 29-31, 1992), ed. by P. GOLINELLI, Bologna 1994, pp. 325-333. 29 COSMA DI PRAGA, Chronicon Boemorum, II, 32, ed. R. KOEPKE, in M.G.H., Scriptores, IX, Hannoverae 1851, p. 88; cf. D. J. HAY, The Military Leadership of Matilda of Canossa (1046-1115), Manchester 2008, p. 169. 30 EADMERI, Historia Novorum in Anglia, ed. M. RULE, in Rerum Britannicarum Scriptores, 81, London 1884 (reprinted 1965), p. 155; the Historia Novorum is considered the “official” life of St. Anselm, while the Vita sancti Anselmi is a pivate version, from which John of Salisbury derived the Life that bishop Thomas à Becket presented to pope Alexander III to obtain Anselm’s canonization: I. BIFFI, Sant’Anselmo nell’interpretazione di Giovanni di Salisbury, in GIOVANNI DI SALISBURY, Vita di Anselmo d’Aosta, a cura di I. BIFFI, Milano 1989, pp. 7-20. 31 EADMER, The Life of St. Anselm Archbishop of Canterbury, ed. cit., pp. 128-129. 8 she had made, to continue the struggle for reform, which was now aimed at defending the primate of England, while she had to give up her greatest desire of leading a life within the peace of the cloister. All this took place when the investiture issue still had not been resolved, and papal diplomacy wavered between official pronouncements of condemnation of episcopal ordinations by laymen, and the need to agree to a final compromise. Both Anselm and Mathilda were victims of this situation, even though the Countess was about to regain an active role in the support of the papacy of Paschal II: she intervened in Parma to replace Bernardo degli Uberti on his rightful see, and she wrote to Paschal II in favour of Anselm who was exiled. Mathilda’s letter was written between the end of 1104 and the beginning of 1105. “It’s indecent [Indecens] – she writes – that such an illustrious member of the Holy Church of Rome, should endure such a long exile … and cannot freely exercise the office which has been granted to him”, and she begs the Pope to intervene32. Mathilda’s plea did not go unheeded and two letters followed: one from Paschal II to Anselm, in which he informed the prelate of the actions he had taken in his favour, and one from Anselm to the King, Henry I, inviting him to change his mind. A compromise was reached just the following year, and, finally, Anselm could return to his see. It was then that, having heard from the monk Alexander, that Mathilda had not received a copy of the text, he wrote her the letter which has reached us, had the manuscript of prayers composed and sent it to Mathilda as a token of his gratitude for the help she had granted “non semel tantum, sed pluribus vicibus”, and as spiritual support for what earthly life was left to the Countess. N. DUFF, Matilda of Tuscany, la gran donna d'Italia, London 1909, p. 293; E. GOEZ – W. GOEZ, Die Urkunden und Briefe, cit., pp. 241-242. 32