Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

advertisement

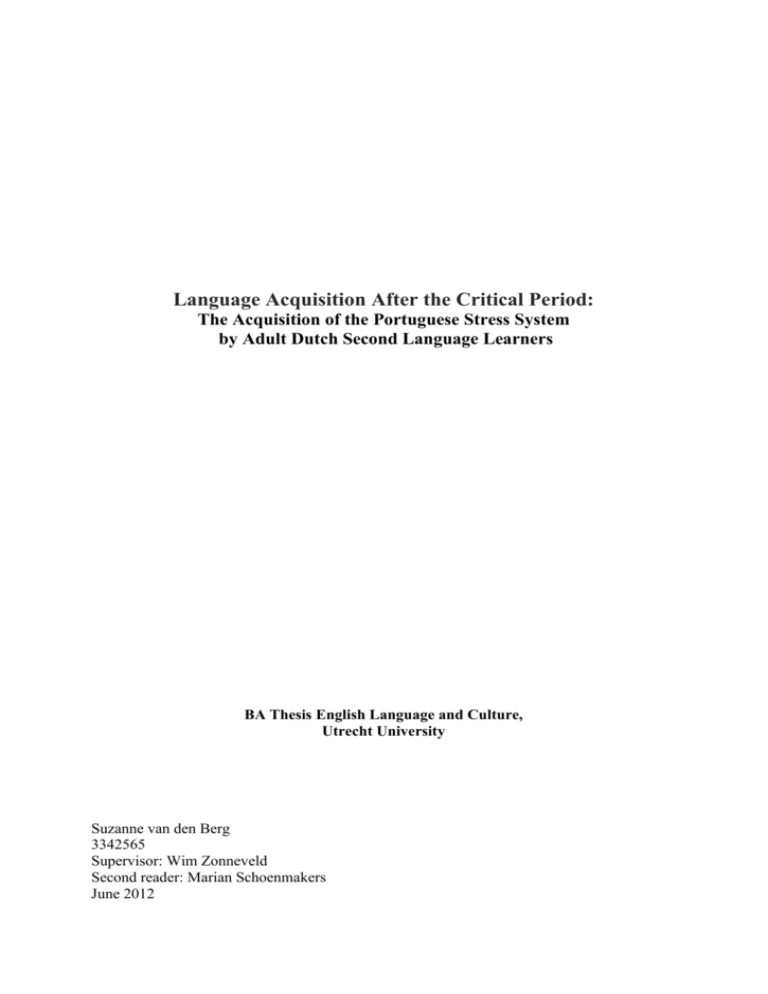

Language Acquisition After the Critical Period: The Acquisition of the Portuguese Stress System by Adult Dutch Second Language Learners BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University Suzanne van den Berg 3342565 Supervisor: Wim Zonneveld Second reader: Marian Schoenmakers June 2012 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………......3 2. Theoretical Framework…………………………………………………………...6 2.1 Universal Grammar and the Critical Period……………………………….........6 2.2 Stress Systems………………………………………………………………….11 2.2.1 The Dutch Stress System……………………………………………….12 2.2.2 The Portuguese Stress System………………………………………….14 3. Methodology…………………………………………………………………….....16 4. Statistics……………………………………………………………………………20 5. Discussion………………………………………………………………………….24 5.1 Correct Items……………………………………………………………………24 5.2 Incorrect Items…………………………………………………………….........26 5.2.1 Incorrect Existing Items……………………………………………. ….26 5.2.2 Incorrect Nonsense Items……………………………………………….29 6. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………36 7. Works Cited……………………………………………………………………….38 8. Works Consulted……………………………………………………….…………39 9. Appendix…………………………………………………………………………..40 3 1. Introduction Two hypotheses of modern linguistics can be seen as the context of this thesis: Universal Grammar and the Critical Period. Since all children all over the world go through the same stages of language acquisition and are capable of acquiring any language, in sometimes less than perfect circumstances, it is believed that there is something like a Universal Grammar that functions as a blueprint for all languages. The knowledge of language that is thought to be represented by this Universal Grammar helps children during the acquisition stages of language. The relative ease with which children acquire their mother tongue and the perfect competence that is usually reached in the first language acquisition process, contrasts with the difficulties many second language learners experience when trying to acquiring a foreign language. This observation leads linguists to believe that the process of second language acquisition is subject to a critical period. Generally, the critical period is believed to end with the beginning puberty. First languages acquisition takes place before this point, which explains its success, second language acquisition often after it, which explains the difficulties. If and to what extent Universal Grammar is still available after the critical period is a question that has kept linguists occupied for years. Some linguists believe that Universal Grammar is completely unavailable after the critical period, which would explain why second language acquisition is such a difficult process. Although it is true that second language acquisition is not always fully successful, some second language learners attain success in certain areas and sometimes to a high degree. This seems to imply that somehow Universal Grammar may be available, although perhaps not to the same extent as during first language acquisition. Here, second language acquisition researchers make a distinction between two components of Universal Grammar: principles and parameters. Principles are thought to be properties all languages have in common. Parameters are universally specified binary options which children need to discover and ‘set’ for their specific language. This distinction may be 4 relevant for second language acquisition research. The principles are the same for every language, and second language acquisition still seems to be governed by them: mistakes do not violate the principles, so they might still be available after the critical period. Thinking in terms of second language acquisition as acquiring a new set of parameter settings, namely those for the second language, it can be questioned whether parameter re-setting is possible. Impossibility of parameter resetting may underlie the difficulties second language learners encounter. This thesis aspires to contribute to this area of research within the framework of principle and parameter theory. Linguistics is a very broad field of research and within this broad field this thesis will concern itself with phonology. It does so by investigating adult second language learners of Portuguese. Concretely, this thesis aims to answer the question whether Dutch beginner to intermediate adult second language learners of Portuguese have developed intuitions, correct or otherwise, regarding the Portuguese stress system. To answer this question, this thesis takes an experimental approach. Dutch university students’ competence in the area indicated will be investigated by means of an oral test. The purpose of this test is to see which intuitions, if any, the second language learners have acquired considering the Portuguese stress system for underived nouns. In this test the subjects were asked to read a number of Portuguese sentences out loud. Half of the sentences will contain existing words to see if the second language learners know the Portuguese system. The other half of the sentences will focus on nonsense words to see whether the second language learners developed intuitions or simply remembered stress patterns of individual words. Stress patterns of nonsense words, never encountered before, cannot be remembered, therefore using them in a test may reveal the extent to which the subjects have correct intuitions. There will also be a group of Dutch/Portuguese bilingual speakers and a control group of native speakers. 5 The Dutch and Portuguese stress system are similar in many aspects, i.e. they have many of the same parameter settings. Since the systems are similar, difficulties in the areas where they are the same are not expected for the second language learners; these parameters do not have to be reset. Where the systems differ, however, difficulties for the second language learners are expected; they need to reset these parameters. This leads to the hypothesis that where the stress systems are the same the second language learners will show full competence but they will have difficulties where parameters need to be reset. Full competence overall, i.e. the same results as the native speakers, is not expected (yet) since these are beginner to intermediate learners. Furthermore, more correct stress placement on the existing words than on the nonsense words is expected. This is especially so since Portuguese places spelled accents on words with an unexpected stress pattern, so it is expected that these will be produced correctly by the second language learners. The native speakers are expected to arrive at full mutual agreement considering the position of main stress. The nonsense words are the only items where full native speaker agreement might not occur. . The structure of this thesis will be as follows. In chapter 2 a theoretical framework for this research will be constructed. This framework will explain the background of the theory of Universal Grammar, the principle and parameter theory, the critical period and discuss the Dutch and Portuguese stress system in detail. Subsequently, the exact methodology of the research will be described in chapter 3, with a depiction of the design of the test, the conduction of the test and a description of the test subjects. Afterwards, the results of the test will be presented in chapter 4, these results will be further examined in the discussion in chapter 5. Finally, in the conclusion in chapter 6, a summary of this thesis will be presented, the limitations of this research will be discussed and some recommendations for further research will be made. 6 2. Theoretical Background In this chapter modern views on the process of language acquisition are discussed. First theories about first language acquisition will be dealt with and then theories about second language acquisition. Finally, a description of the Dutch and Portuguese word stress system will be given within the framework of these theories. 2.1 Universal Grammar and the Critical Period There are many theories about how children acquire language. First let us take a look at the way children do not learn languages. Generally, people tend to think that children learn merely through imitation. Investigators dealing with language acquisition quickly find out that this is unlikely. First of all this view does not explain the type of mistakes that are found in child speech. In Victoria Fromkin’s an Introduction to Language she explains that “Children do not hear words like holded or tooths or sentences such as Cat stand up table or…other utterances they produce”(Fromkin, 315). Second, when children are corrected they are often not capable of repeating the correct sentence. They can in fact literally not imitate. “[T]hey are unable to produce sentences that they would not spontaneously produce”(315). Lastly, there is the issue with the so-called poverty of the stimulus i.e. “we end up knowing a lot more about language than is exemplified in the language we hear around us”(319). Not only will children not hear every possible sentence in their language, the language they do hear is not always correct. In Universal Grammar and Second Language Acquisition Lydia White explains that “[a]dults make mistakes, hesitate, change their minds about what they are going to say, etc”(White, 12). Thus, the input to the learning process is far from uniform and in many ways inadequate, still all children end up with, more or less, the same level of competence. 7 Two other theories are that children learn through positive reinforcement or analogy. First, let us take a look at positive reinforcement. If children would learn in this manner that would mean that when they say something correct they would receive positive reactions and negative responses when they make mistakes. Research, however, shows that this is not what occurs, parents usually do not correct the child and when they do it is more about content than syntax (Fromkin, 316). When parents do correct the child, the child is not able to adjust its speech to the newly gained information and keeps making the same mistakes, as stated earlier. Finally, children do not learn by means of analogy either. Analogy implies “hearing a sentence and using it as a sample to form other sentences”(Fromkin, 316). For example, an English child learns how to make questions: The girl is happy. Is the girl happy? The child now knows that to make questions it must “move the auxiliary to the position preceding the subject.” What will happen then when the child hears the more complex sentence? The girl who is happy is singing. Based on analogy it would form a question in the first way represented below, rather than the second: *1Is the girl who happy is singing? Is the girl who is happy singing? “Studies of spontaneous speech … show that children never make mistakes of this sort”(Fromkin, 317). If children do not learn through imitation, positive reinforcement or analogy, then how do they acquire language? When a child is born it can learn any language; an adopted child from China raised in England does not end up speaking Chinese, but English. In his reader 1 An asterix indicates that an item is incorrect. 8 Phonetics and Phonology, Wim Zonneveld explains “[o]bviously, the child does not know beforehand which language it is supposed to go and speak – this situation is known as the Language Lottery”(6), a term coined by the Canadian linguist David Lightfoot. A child can learn any language and at the same time (almost) all children go through the same stages of development during language acquisition. As Martin Kaltenbach states in Universal Grammar and Parameter Resetting in Second Language Acquisition children “do so despite different social and cultural backgrounds, no matter whether they grow up as a single child or in bunches of kids, in towns or in rural areas, with many peers or just their parents to talk to”(11). “These factors lead many linguists to believe that children are equipped with an innate template or blueprint for language”(Fromkin, 319). This blueprint is referred to as Universal Grammar. “Knowledge of language, technically known as linguistic competence, is assumed to be represented in the form of a generative grammar, an abstract system of principles and rules which produce the grammatical sentences of a language”(White, 1). The problem with the poverty of the stimulus is solved by this theory as well. The child already has subconscious knowledge of language so it will end up, as an adult, with a complete grammar even though it did not receive complete or completely perfect input. “If children have built-in knowledge of what a grammar must be like, then the presence of degenerate data will not mislead them into false hypotheses because they will know in advance that certain kinds of analyses are ruled out”(White, 12). Children have an innate knowledge of language. This is in fact unconscious knowledge, “most people are not aware of the systematic nature of their language and cannot articulate the rules and principles that they in fact follow”(White, 2). This knowledge consists of language universals and language-specific details. These language specific details need to be filled in the for the specific language the child is acquiring. The language universals are the same for every language. “UG provides a kind of blueprint as to what the grammar will be 9 like, but details can only be filled in by input from the language being learned”(White, 16). Not all universals are used by all languages though. “It is important to reali[s]e that although the principles of UG are universal, this does not mean that every principle necessarily operates in every language”(White, 29). There is a universal range of sounds available to languages, for instance, but languages do not use all these sounds, rather they make their own limited selection; the same holds true for language universals. Another name for universals is principles and language-specific details are filled in by parameters. Parameters are binary choices within a language which need to be set by the child. “The function of the input data in language acquisition is to help fix one of the possible settings. This is called triggering”(White, 29). For instance, a parameter which has to be set is whether the head of compound words is on the right or the left. This parameter will be set by children in languages where compounds are allowed. An example from Dutch to illustrate: ‘putwater’ ‘waterput’ (water from a well) (a well with water in it) In Dutch, the head is on the right hand side of the compound, which decides the meaning as well as the compound’s gender, expressed here in the choice of definite article (‘het putwater’ vs. ‘de waterput’ for ‘het water’ and ‘de put’). In Dutch the parameter for the head of words would be set to the right. In a language different from Dutch, compounds could be leftheaded, for instance. The theory of Principles and Parameters states that children already know the principles (i.e. universals) that count for all languages. Furthermore, children need to “learn” how the parameters are set for their language. In the above example, they would need to learn whether the head of a word is on the right or on the left. In this way, the process of language acquisition can be described as parameter setting. Compared to the ease with which children acquire their native tongue, adults trying to learn a second language have a much harder time. Whereas “All first language learners are 10 totally successful,” adult learners “on the other hand … fail to acquire the target language fully; there are often clear differences between the output of the L2 learner and that of native speakers, and learners differ as to how successful they are”(White, 41). Many linguists ascribe this to the idea that there is a critical period for language acquisition. Just like a body stops to grow at a certain age so does the ability to acquire a language. As Strozer explains in Language Acquisition after Puberty: “During an early period of their life, and only during this period, humans have a capacity for mastering languages natively, the brain being modified in specific ways during these formative years under the influence of mere language exposure; this capacity cannot be exercised after the period is over.”(136) “[T]he end of [the] Critical Period for language can be equated with ‘the onset of puberty’, when crucially the flexibility of the relevant part of the brain is affected”(Zonneveld, 8). The idea of a critical period for language acquisition could underlie the difficulties adult second language learners typically have. There are many different hypotheses about the availability of UG after the critical period. In principle, there seem to be three options: UG is fully available during second language acquisition (L2A), UG is completely unavailable during L2A and UG is partially available through the first language (Kaltenbacher, 27). There are many versions of the last option, for instance “[l]earners are assumed to transfer their L1-internal grammars and restructure them via UG-operations upon being confronted with L2-data that cannot be accounted to an L1-configurations”(Kaltenbacher, 31). Currently, many linguists believe that “the invariant principles of language … continue to play a role beyond the critical period for all normal humans”(Strozer, 141). but that “the thesis that adults are capable of setting the parameters in the process of foreign language acquisition has not been demonstrated”(Strozer, 11 156). This would imply that learning the language-specific aspects of the second language would be difficult, which is in line with what is actually found. 2.2 Stress Systems One of the fields of linguistics that uses the theory of Universal Grammar is Phonology. In Phonology a Cognitive View, Jonathan Kaye describes phonology as “the study of the systems of linguistically significant sounds”(1). The goal of phonology, as Zonneveld describes is “to contribute to the study of UG by studying the sound properties and sound behaviour in languages”(1). An example of what phonology concerns itself with is word stress. Not all languages are word stress languages, but in languages that fall in this category word stress is the phenomenon that “[i]n polysyllabic words (those with more than one syllable), one syllable is always produced in a more prominent fashion than the others”(Kaye, 139). In English, for instance, in the word agenda the syllable - gen – is the single syllable that carries the main stress of the word. Stress is a word-edge phenomenon, which means that in word stress languages main stress is always put close to a word edge, left or right. Kaye argues that word stress exist to facilitate knowing where word boundaries are, he calls this parsing (5051). There has already been a lot of research done in this area in relation to UG. “Stress systems can … be defined in terms of a small number of parameters along which one system can vary from another”(Kaye, 143). One of these parameter settings is whether the main stress is on the left of the word or on the right. Another one is whether the stress pattern is iambic or trochaic (stress alternates between syllables, stressed/unstressed/stressed/ etc. or unstressed/stressed/unstressed etc.). “Compound words, although obviously words, ‘do not count’ in this discussion: they have their own stress pattern”(Zonneveld, 41). Specifically, we are talking about morphologically non-complex, underived nouns. To see how parametric theory works in a concrete example, the word stress system of Dutch will be described. 12 2.2.1 The Dutch Stress System For the Dutch language the stress system works as follows: “Dutch is a right-edge trochaic language (implying that basically [this] language [has] stress on the prefinal syllable)”(Zonneveld, 40). The stress pattern of a normal Dutch word depicted in a grid: x x x x x x (single) main stressed syllable stressed syllables syllables of words x Examples of words that conform to this basic pattern are ‘kilo’(kilo), ‘familie’(family) and ‘macaroni’(macaroni): x x x ki x lo x fa x x x mi x lie x x ma x ca x x x ro x ni Other options for main stress in Dutch are the final syllable or the antepenultimate syllable (pre-prefinal). There are two other parameters that need explanation for the Dutch system to become completely clear. The first is the quantity-sensitivity parameter, asking whether syllable weight plays a role. An open syllable (ending in a vowel) is light and a closed syllable (ending in a consonant) is heavy. There are also superheavy syllables, those that either end in two vowels followed by a consonant or one vowel followed by two consonants. If a syllable is heavy and the weight-parameter says yes it will get stress(not necessarily main stress though). In Dutch quantity-sensitivity plays a role, which explains words as ‘vulkáán’(volcano), ‘presidént’(president) and ‘proletariáát’(proletariat)(Zonneveld, 42). Their grids would look like this: x x vul x x x kaan x x pre x si x x x dent x x pro x le x x ta x ri x x x aat 13 The second parameter explains why for instance the word ‘álfabet’(alphabet) does not have final stress but antepenultimate stress. * x x al x fa x x x bet x x x al x fa x x bet In Dutch heavy syllables are extrametrical. This means that if a word ends in a heavy, but not a superheavy, syllable that syllable is ignored when assigning the trochee and main stress. This explains the stress pattern of for instance ‘Madagaskar’(Madagascar): x x Ma x da x x x gas x x kar There are some exceptions to these rules in Dutch. There are words that do not end in a heavy syllable, i.e. that end in a vowel, that get exceptional extrametricality. Consider ‘ánimo’(enthusiasm) and ‘harmónika’(harmonica): x x x a x ni x x mo x x har x x x mo x ni x x ka Furthermore, there are words that do end in a heavy syllable that do not get extrametricality. Consider ‘klarinét’(clarinet) and ‘pelotón’(platoon): x x kla x ri x x x net x x pe x lo x x x ton These cases are exceptional though. Summarising, the parameter settings for Dutch are: main stress is on the right, the stress pattern is trochaic, yes to quantity sensitivity and also yes to extrametricality. 14 2.2.2 The Portuguese Stress System Turning to Portuguese, the target language of this thesis, there still seems to be a lot of disagreement considering its stress system. Arguing in terms of parameters, just as we did for Dutch, the following picture emerges. Marina Vigário states in her book The Prosodic Word in European Portuguese that “EP word stress can fall on one of the last three syllables of a word”(65). The first parameter choosing between left-edge or right-edge is therefore the same as in Dutch; main stress falls on the right-edge of the word. In Acquisition of Primary Word Stress in European Portuguese Susanna Correia claims that the second parameter, choosing between an iambic or trochaic pattern, is set to trochaic, just like in Dutch (12). Examples of this pattern are ‘vida’(life), ‘cidade’(city) and ‘oceana’(ocean): x x x vi x da x ci x x x da x de x x o x ce x x x a x na Weight sensitivity is a hotly debated issue. Correia, however, states that weight sensitivity could play a role. “In the nouns' system, heavy syllables, … ending in a consonant (r, l, s) or a glide overwhelmingly bear stress … Syllable weight counts for stress assignment directly and indirectly at the Rhyme level (i.e., syllables are heavy at the level of the Rhyme and at the level of the Nucleus ‐ /VC, VG, VN, VNC, VGC, VGN, VGNC/) ‐ e.g., balão 'balloon', carapáu 'mackerel', rapáz 'boy', amár 'love', anél 'ring'.”(47) Furthermore, there is never stress on the antepenultimate syllable if the prefinal syllable is heavy. Therefore, basically the Portuguese system seems to be trochaic, quantity sensitive, simply without extrametricality, resulting in penultimate or final stress. Even so, antepenultimate stress is found. Within the system these cases must be accounted for by some form of extrametricality, just like in Dutch. 15 Examples of words with antepenultimate stress are ‘matemática’(mathematics) and ‘estômago’(stomach): x x ma x te x x x má x ti x x ca x es x x x tô x ma x x go These patterns show exceptional extrametricality (just as the Dutch ‘ánimo’ and ‘harmónica’); the final consonants are not heavy. There are no cases of antepenultimate stress in Portuguese where the final syllable ends in a consonant (-VC). This is where the two languages are different. In Dutch heavy but not superheavy syllables are extrametrical, in Portuguese these cases (if they exist) are exceptions. There seems to be a systematic parametric difference between Dutch and Portuguese considering the extrametricality rule. The exact nature of extrametricality is not completely clear and there is no fully accepted theory of Portuguese yet. The difficulty for Dutch speakers acquiring the Portuguese stress system will probably be the absence of systematic –VC extrametricality in Portuguese. According to the principle and parameters theory, acquiring a language is the acquisition of the parameter settings of the target language. In regards to word stress this means finding the correct setting for parameters such as the iambic-trochaic choice, the word edge choice, quantity sensitivity and extrametricality. In the case of second language acquisition after the critical period the parameters are already set for the first language. The question is whether these parameters can be reset for the second language that is being acquired. This question can be seen as the context of the remainder of this thesis. 16 3. Methodology In this section the methodology of this thesis’ research will be described. First, there will be a description of the design of the test. Then there will be a description of how the actual investigation was conducted. Finally, there will be a brief description of the test subjects. As explained in the Introduction, the focus of this test is to see whether or not Dutch second language learners of Portuguese have developed intuitions regarding the Portuguese stress system. In order to create a more natural test environment, the test items were put in natural sounding sentences. The test consists of 36 Portuguese sentences, in all the sentences one (and in six cases two) underived noun is the focus of the test. These sentences were divided in sentences with existing words and sentences with nonsense words. In total there are 42 words in the test, 21 existing and 21 made up. The existing words are divided again, in two groups, words with an accent in the spelled form that indicates where the main stress is and words without an accent. These sentences are part of the test to see if the subjects know the Portuguese stress system for existing words and to see if the students have the competence to produce the right word stress when there is a written accent. Joe Pater claimed in Metrical Parameter Missetting in Second Language Acquisition that in a test using only existing words “nothing rules out the possibility that [...] relatively advanced second language learners simply memori[s]e the pronunciations of individual words, rather than come to any sort of generali[s]ation about the stress system as a whole. This alternative is especially plausible for the acquisition of a system as complex [...] as that of English.”(235) The nonsense words are there to eliminate the chance that the subjects have simply memorised where the stress is for individual words. In this way we can see if they have 17 acquired intuitions or not. The nonsense words are ‘accidental gaps’ in the Portuguese language, i.e. words that do not exist but could, given their phonological structure. As discussed earlier, Portuguese words can have ultimate, penultimate and antepenultimate main stress. Words with antepenultimate stress always have a spelled accent to indicate this, i.e. when there is an accent, the spelling visually aids the reader to know where the main stress is. The test consists of words that show all the three stress patterns the Portuguese language allows for underived nouns. Furthermore, all the cases where Portuguese would get final stress are represented. Final stress is expected for words (without an accent) ending in –l, -r, -z and -au. Finally, there are some nonsense words put in the test that would probably get an accent if they existed. In Portuguese words ending in –io and -ica very often have antepenultimate stress indicated with an accent. For example, necessário (necessary), adversário (adversary), advérbio (adverb), matemática (mathematics), apologética (apologetics) and túnica (tunic). Exceptions of this rule are words like, assobio (flute), concilio (council) and botica (pharmacy). Nonsense words with these endings can also be found in the test to see whether the subjects know this rule. The Portuguese sentences and their translations can be found in the appendix. The sentences with nonsense words are as neutral as possible. The fact that the words do not exist is hopefully not immediately obvious to a subject relatively new to the language. Expectantly, the subject will think it is a existing word that they just have not encountered yet. To make sure there are no grammatical mistakes and other things in the test to throw the subjects off a native speaker helped me construct the sentences, since Portuguese is not my native language either. The test subjects were given the 36 sentences on separate cards. The subjects were asked to read these sentences out loud in the presence of the test conductor, who was the author of this thesis. Their reading of these sentences was recorded on a tape recorder. The 18 order of the sentences was random and shuffled after every reading, for the next subject. This was to avoid bias in the results that could be caused by a certain order of the sentences. The test subjects were unaware of the focus of the research beforehand, also to prevent bias. The test subjects consisted of a group of 9 second language learners of Portuguese who started studying the Portuguese language after the critical period had passed. All second language learners started learning Portuguese after the age of 18. Their level of Portuguese can be described as beginner to intermediate, generally they have studied Portuguese for at least half a year. Furthermore, there were 4 bilingual test subjects. These subjects had one parent with Portuguese as their mother tongue and one Dutch parent. One of these subjects, however, turned out to be dyslectic and because of this had great difficulty with the reading of the nonsense words. These words were often pronounced completely differently from what was written. This was an interesting experience, but this subject was not used for the results of the test. Finally, there was a group of 5 native speakers of Portuguese functioning as a control group. What this group does will be seen as correct, or ‘target Portuguese’ in the context of the test. What can be predicted by the rules of the Portuguese stress system is not what matters but what the actual speakers of the language do – although there is expected to be a perfect match between the two. The second language learners were all tested individually in the hallway of university buildings. Apart from the occasional by-passer the test conductor and the subject were alone. On one occasion the test had to be interrupted for a brief moment because a large group passed but aside this interruption all the tests went smoothly and in one session. Two bilingual subjects and two native speakers were investigated under the same circumstances. The remainder of the subjects were investigated in their own homes in a separate room alone with the test conductor. 19 The tape recordings of the readings were listened back to by the researcher and one other speaker of Portuguese in order to prevent bias and to be sure that the main stress was heard correctly. In many cases the two observers listened to individual cases multiple times to eliminate all doubt. In the next section the results of this investigation will be discussed. 20 4. Results In this chapter the results of the Portuguese word stress experiment will be presented. As stated earlier 5 native speakers, 4 bilingual speakers and 9 adult second language learners of Portuguese were the subjects of the experiment. They were asked to read out loud 36 sentences which contained 42 test items and the stress patterns they produced for these words were scored. In chart 1a on the next page the overall results are represented. For every word it is shown where every group of speakers put the main stress: antepenultimate, penultimate or final. As stated earlier, Portuguese represents exceptional cases of stress by spelled accents. First the results of the existing words with a spelled accent and then the existing words without an accent are shown, then the results of the nonsense words. The results are first organised per group of speakers and then per stress position, in this way it is easier to see the different main stress used within a group. It is, however, a bit harder to see agreement between the groups, this is why the appendix also contains a chart 1b representing the results organised per main stress position first. The first number in a cell is the number of speakers who used stress in that position of the word. The second number in a cell is the percentage of speakers from the specific group that used stress in that position. 21 * = one second language learner put stress on the initial syllable 22 The words with a written accent posed no difficulty for any of the speakers. Neither did the existing words for the native speakers, but here the second language learners are already a bit less successful. The nonsense words pose the real difficulty, especially for the second language learners who only showed 100% agreement in half of the items. These overall results will be commented on further in the Discussion chapter of this thesis. Another way of interpreting these results is to look at the number of words where all the speakers of one group had full agreement on the position of main stress. In this manner we can see in how many cases all the speakers had the same intuitions. As we can see in the first chart, interestingly when there was no 100% agreement between native speakers there was never full second language learner agreement either. Chart 2a Number of words with 100% agreement Speakers Native Bilingual Existing words with accent 7 7 Existing words without accent 14 13 Total 21 20 Average 100% 95.2% Nonsense words 15 17 Average 71.4% 81.0% Total 35 37 Total Average 83.3% 88.1% Learner 7 9 16 76.2% 11 52.4% 27 64.3% From chart 2a and chart 1a combined it becomes clear that the words with accents did not give any of the speakers any difficulty. The second language learners have the competence of putting the stress in the correct place when there is a visual representation, as was expected. When these results are ignored, chart 2b below is the result. Number of words with 100% agreement (without the words with accent) Speakers Native Bilingual Learner Existing words 14 13 9 Average 100% 92.9% 64.3% Nonsense words 15 17 11 Average 71.4% 81.0% 52.4% Total 29 30 20 Total Average 82.9% 85.7% 57.1% 23 In chart 2b it seems as if there was more group-internal agreement among bilinguals than among the native speakers. However, looking at the number of items rather than the number of words with full agreement, it can be observed that the native speakers did in fact produce fewer incorrect sentences than the bilingual subjects. The following charts 3a and 3b are based on the number of correctly produced items according to native speaker majority. It is considered a majority when more than half of the native speakers assign main stress to that position, i.e. when three or more native speakers assign main stress to the same position. It never occurred that native speakers did not have a majority for one word. Chart 3a. Number of correct items (According to native speaker agreement) Speakers Native Bilingual Learner Existing words with accent 35/35 21/21 63/63 Existing words without accent 70/70 41/42 114/126 Average 100% 98.4% 93.7% Nonsense words 97/105 57/63 161/189 Average 92.4% 90.5% 85.2% Total 202/210 119/126 338/378 Total Average 96.2% 94.4% 89.4% When the words with an accent are ignored this leads to the following chart 3b. Number of correct items (According to native speaker agreement) Speakers Native Bilingual Learner Existing words 70/70 41/42 114/126 Average 100% 97.6 90.5% Nonsense words 97/105 57/63 161/189 Average 92.4% 90.5% 85.2% Total 167/175 98/105 275/315 Total Average 95.4% 93.3% 87.3% Overall, the second language learners did not produce very much incorrect output. Their output is best for the existing words, which are probably familiar to them. The bilingual subjects get very close to a native level although their intuitions regarding the nonsense words sometimes differ from those of the native speakers, as a group. A complete discussion of the results can be found in the next chapter, the discussion chapter, of this thesis. 24 5. Discussion In this chapter the results of the test constituting the experimental core of this thesis will be discussed. As chart 2b in the results chapter shows in 57.1% of the cases the second language learners had 100% agreement on where the stress should be. So in 42.9% of the cases there was disagreement. First, there will be a discussion of the words where there was full agreement among the second language learners. Then, all the individual instances where there was no 100% agreement will be discussed, beginning with a discussion of the words where there was 100% native agreement, where the existing words will be discussed first and the nonsense words next. Then the nonsense words will be dealt with for which there was no full native agreement either. Finally, some words will be discussed in groups when there are similar stress patterns. 5.1 Correct items As expected the second language learners produced all the existing words with an accent correctly. Out of the nine existing word without an accent that were produced correctly, four(‘arroz’(rice), ‘bacalhau’(codfish), ‘senhor’(sir) and ‘viagem’(trip)) would get assigned different main stress if they had been Dutch. These words and their Dutch and Portuguese stress patterns are presented here: Dutch: x x x x x ar roz Portuguese: x x x x x ar roz x ba x x ba x x x cal x hau x x cal x x x hau x x x sen x x hor x sen x x x hor x x x vi x a x x gem x vi x x x a x gem 25 These items show that the second language learners are not simply imitating the Dutch system. To be certain that they have acquired intuitions and are not simply remembering every individual word and its stress system, the correct items of the nonsense words will now be discussed. Out of the eleven nonsense words that were produced correctly, four would get assigned different main stress if they had been Dutch. These words and their Dutch and Portuguese stress patterns are presented here: Dutch: x x x x ce ri x x tal x x x la x do x x ver x x x de x na x x tor x x x ples x na x x x tor x x ples x ta x x dor x ta x x x dor Portuguese: x x ce x ri x x x tal x x ver x x x la x do x x de These items prove that the second language learners did not simply remember individual stress patterns for every new word they learn. The second language learners demonstrate that they are also able to correctly assign stress to words they have not encountered before and are not simply copying the Dutch system. 26 5.2 Incorrect Items The second language learners were not always completely successful though, as shall be discussed next. As a start of the discussion of words for which there was no 100% agreement between all the speakers, consider chart 3 below. As the chart shows, for six existing words and nine nonsense words there was no 100% agreement between groups. 5.2.1 Incorrect Existing Items Here follows a discussion of the existing words one by one. Aparelhagem(equipment): Both the native speakers and bilinguals correctly placed stress on the penultimate syllable. Seven second language learners did this too, but two chose final stress. These two speakers did not use the normal Portuguese stress system which would give penultimate main stress, but they did not use the Dutch system either. Had they used the Dutch system they would have arrived at antepenultimate stress since the final syllable –gem would be extrametrical. The reason two second language learners used an unexpected stress 27 pattern may be due to the fact that ‘aparelhagem’ is a relatively difficult and long word. Not only the second language learners who assigned incorrect stress had difficulty pronouncing the word i.e. the second language learners hesitated, repeated the word or stammered, but only two ended up with a different main stress position. Assobio(whistle): As the native speakers show and as is predicted by the Portuguese stress system the main stress for ‘assobio’ should be penultimate. One bilingual subject and one second language learner put the stress on the final syllable and four second language learners put it on the antepenultimate syllable. ‘Assobiou’ is the third person simple past form of the verb ‘assobiar’ which means to whistle. The two speakers who put stress on the final syllable pronounced the word as if was ‘assobiou’, not ‘assobio’. The word ‘assobiou’ has final stress, so these two speakers might have misread or otherwise misinterpreted the word. In the context of the sentence the -ou interpretation of the word can also be correct. “‘Assobio na noite’ é um conto de Lidia Jorge” means “‘(the) Whistle in the night’ is a story by Lidia Jorge” and “‘Assobiou na noite’ é um conto de Lidia Jorge” means “(he) Whistled in the night’ is a story by Lidia Jorge.” If the bilingual subject and the second language learner subject interpreted the sentence this way, they are not incorrect by placing the stress where they did, they are only incorrect in their reading. The results of the four other second language learners, however, cannot be explained in this manner. We will look at them later in the context of additional observations. Bijutaria(jewellery): Both the native speakers and bilinguals correctly placed stress on the penultimate syllable. Most second language learners did this too, but two placed stress on the antepenultimate syllable. We will look at them later as well. Futebol(football): Both the native speakers and bilinguals correctly placed stress on the ultimate syllable. Only one second language learner differed from this pattern, placing stress on the penultimate syllable: ‘futébol’. An explanation for this result cannot lie in the 28 Dutch word stress system. The syllables of the word are divided like this: fu-te-bol. If this word is interpreted as an underived word, it has a structure similar to the Dutch ‘horizon’(horizon). In Dutch the stress pattern would be: x x x fu x te x x x ho x x bol x ri x x zon The word for ‘futebol’ in Dutch is ‘voetbal’ and it can also be imagined that, based on the word’s meaning, transfer from Dutch could take place. This would result in the same main stress: Dutch ‘vóet-bal’ to Portuguese ‘fú-te-bol’. Transfer from prefinal stress in Dutch ‘vóetbal’ to prefinal stress in Portuguese ‘fu-té-bol’ would be highly unlikely. Maybe this speaker assigned stress as if the final –l did not make that syllable heavy, resulting in prefinal stress. It may also just be one deviant utterance: the word ‘legal’(legal), also ending in –l, did get 100% correct final stress by the second language learners. Grelhador(broiler): Both the native speakers and bilinguals correctly placed stress on the final syllable. Most second language learners did this too, but two placed stress on the antepenultimate syllable. In Portuguese words ending with an –r receive stress on the final syllabe, most second language learners show that they know this rule. The other two probably used the Dutch system. In the Dutch system the word ‘grelhador’ can be compared to the Dutch words ‘alfabet’(alphabet) and ‘labrador’(Labrador). As was discussed in the theoretical framework chapter, ‘álfabet’ is an example of a Dutch word with extrametricality, as is ‘lábrador’. If ‘grelhador’ were a Dutch word it would also have ‘dor’ as an extrametrical syllable, which would lead to the following stress pattern, equal to ‘alfabet’ and ‘labrador’: x x x grel x ha x x dor x x x la x bra x x dor x x x al x fa x x bet 29 Here it can clearly be seen that two speakers used the Dutch stress system when assigning stress to a Portuguese word. Strangely enough the nonsense word ‘plestodor’(which has a similar syllable pattern) was produced with final stress in 100% of the cases. This shows that these speakers do know the rule that words ending in an –r receive stress in Portuguese but it is not completely stable yet. Apparently, speakers are not yet able to apply it automatically to all relevant cases, occasionally Dutch interferes. This concludes the existing words section of the discussion. In general the second language learners showed a good competence in assigning Portuguese main stress. The second language learners did not follow the native speakers in 12 out of 189 items. This means that 93.7% of the cases were correct and when the words with an accent are ignored, 90.5% of the cases were correct, as chart 3b in the results chapter shows. In general, it can be said, that the second language learners are able to produce correct main stress in most cases. 5.2.2 Incorrect Nonsense Items First the four words with a 100% native agreement will be discussed, followed by the words without full native agreement. Altagem: For this word all the speakers agreed on penultimate main stress except for one second language learner. This subject put main stress on the antepenultimate syllable. This is comparable to what happened to the existing word ‘grelhador’, the Dutch system would assign main stress to the antepenultimate syllable this shows in the subject’s output. Again the syllable structure that would get antepenultimate main stress in Dutch but not in Portuguese turns out to be difficult for a Dutch learner. Pirnaz: Both the native speakers and the bilingual subjects put the main stress on the final syllable, this was what was expected since the word ends in an –z. The second language learners did not fully agree on this case. Six selected final stress but three put stress on the 30 single other syllable, the penultimate one. The two other words ending with a –z in the test, ‘arroz’(rice) and ‘veraduz’, did - correctly - get 100% final stress. ‘Veraduz’ has a different syllable structure from ‘arroz’ and ‘pirnaz,’ but ‘arroz’ and ‘pirnaz’ both start and end with closed syllables. ‘Arroz’ is a very common Portuguese word so the fact that stress was assigned correctly to this word could be because of its familiarity. That is to say, this could be an example of word learning including the position of main stress for this specific word but not internalising the (or any) rule. The syllable structure of ‘pirnaz’ is similar to Dutch ‘harnas’(armour) In Dutch the main stress for ‘pirnaz’ would be on the penultimate syllable: Dutch: x x x har x x x pir x x nas Portuguese: x x naz x x pir x x x naz Apparently, three second language learners used the Dutch system. Raperial: Both the native speakers and the bilingual subjects put the main stress on the final syllable, which was what was expected since the word ends in an –l. One second language learner put the stress on the antepenultimate syllable. The syllable structure of ‘raperial’ is comparable to the Dutch word ‘accordeon’. If the Dutch extrametricality rule is applied to this word it would lead to the following stress pattern: x ra x x x pe x ri x x al x ac x x x cor x de x x on Again, it seems the Dutch system was used to assign main stress instead of the Portuguese system. One second language learner did something very peculiar: he put stress on the initial syllable. This does not exist in the Portuguese system nor does it occur in the Dutch system, since both systems only accept antepenultimate, penultimate or final main stress. The subject did not combine the final two vowels to one diphthonged vowel either, which would turn the word into a trisyllabic word: ra-pe-rial. An explanation could be that the speakers expected 31 the word ‘rápido’(quick) which begins with the same three letters as ‘raperial’ and has stress on the ‘ra’ syllable. Aside from this association there is not a similar stress pattern in either of the two languages. Trajeiro: Both the native speakers and the bilingual subjects put the main stress on the penultimate syllable. Two second language learners put the main stress on the final syllable. This cannot be explained by the Dutch extrametricality rule nor by the Portuguese system. In the context of the sentence it was very clear that ‘trajeiro’ was a noun and not for instance a verb (which have different stress rules) because it was preceded by a possessive pronoun. This is an especially peculiar case since it is not just one second language learner that assigned final stress. Next the nonsense words without full native speaker agreement will be discussed. Balania: The majority of native speakers assigned main stress to the antepenultimate syllable; one though selected the penultimate syllable. One of the bilingual speakers also assigned main stress to the antepenultimate syllable but the other two the penultimate one. The second language learners were completely divided; five chose antepenultimate and four penultimate main stress. An explanation for this difference between native speakers could be that words ending in –ia often have antepenultimate stress, but this is always indicated with a written accent. The native speakers obviously know this rule and even without the visual aid of an accent know to place main stress on the antepenultimate syllable, except for one who may have focussed on the spelling. Some of the second language learners have also picked up on this trend in Portuguese. We will discuss ‘balania’ further when other results can provide more context. Grinestia: The majority of native speakers assigned main stress to the antepenultimate syllable but one selected the penultimate syllable. Two of the bilingual speakers also assigned main stress to the antepenultimate syllable and one assigned it to the penultimate syllable. The 32 majority of the second language learners selected penultimate main stress for this word, two, however, assigned stress to the antepenultimate syllable. Just as the case of ‘balania’ the native speakers know that word ending in –ia often get antepenultimate stress in Portuguese, again one subject apparently focussed on the spelling. The second language learners are not consistently applying this rule yet; compared to ‘balania’ three less second language learners assign antepenultimate main stress. The word ‘grinestia’ will be further discussed below. Lastario: The majority of native speakers assigned main stress to the antepenultimate syllable but one selected the penultimate syllable. All the bilingual subjects assigned antepenultimate stress. Most of the second language learners also assigned antepenultimate stress, only one selected penultimate stress. As discussed in the chapter on methodology, the word ‘lastario’ was put in the test to see if the second language learners knew the general rule of Portuguese that (almost) all words ending in –io get antepenultimate stress. The majority of these learners show that they know this rule even when they do not see an accent to indicate this. The one who did not assign main stress to the antepenultimate syllable shows that he did not notice this tendency in Portuguese (yet). This word will be discussed later, too. Lintagel: It is hard to speak of a majority of native speakers in this case, since three subjects assigned penultimate stress and two final stress. The bilingual subjects all assigned penultimate stress and among the second language learners seven assigned penultimate stress and two final stress. Final stress would be expected since ‘lintagel’ ends in an –l, but neither an overwhelming number of the native speakers nor any of the bilingual speakers assigned final main stress. The exact opposite happened, most subjects assigned penultimate stress. This might be due to the fact that many adverbials in Portuguese end with –ável e.g. ‘aceitável’(acceptable) and ‘sociável’(sociable). This might have caused the way the stress was assigned. 33 Meratica: Again there was no clear native speaker agreement; three assigned penultimate stress and two antepenultimate stress. Two of the bilingual subjects assigned antepenultimate stress and one penultimate stress. The second language learners were just as divided as the native speakers; five assigned antepenultimate stress and four penultimate stress. As explained in the methodology chapter the word ‘meratica’ was put in the test to see if the second language learners knew that most words in the Portuguese language ending in –ica get antepenultimate stress. As can be seen, however, there is no native speaker agreement on this rule: in actual fact, more native speakers assigned penultimate stress than antepenultimate stress. The small number of subjects obviously is a handicap here: using a bigger control group it might become clearer if word ending in –ica usually get antepenultimate stress. i.e. if this actually is a sub rule of Portuguese. Verarem: In all of the groups all of the speakers except for one assigned penultimate stress to this item. The one exceptional subject in every group assigned final stress. If the second language learner had used the Dutch system, the final syllable of ‘verarem’ would have been extrametrical and the main stress would be on the antepenultimate syllable. This, however, is not what happened. For some reason, some of the speakers thought that words ending in –m also get final stress. The same thing occurred with the word ‘aparelhagem’. They did not do this for the word ‘viagem’(trip), here there was 100% agreement on penultimate stress. This might be due to the familiarity of the word. Again, this probably is an example of learning a word including the main stress without a rule underlying the output.. This concludes the discussion of the nonsense words without full native agreement. Finally, two groups of words will be discussed in further detail. These words are grouped according to their word endings. Necessário, assobio and lastario: ‘Necessário’(necessary) is an example of a word ending in –io which gets main stress on the antepenultimate syllable. This word was put in the 34 test to see whether the subjects have the competence to put main stress on the right syllable if they have a visual aid. They showed 100% capability to do so. For the nonsense word ‘lastario’ most of the second language learners also applied this rule; just like the native speakers they assigned word stress to the antepenultimate syllable. This shows that they know that in general words ending in –io get antepenultimate stress. This also explains why the existing word ‘assobio’ gave the second language learners so much difficulty. Four of them over-generalised this rule and arrived at the wrong stress pattern. Bijutaria, balania and grinestia: For all three of these words the Portuguese stress system predicts penultimate stress, since there is no accent in the spelling to indicate otherwise. Words ending in –ia in the Portuguese language sometimes get antepenultimate stress but not nearly as often as words ending in –io. For ‘balania’ as well as ‘grinestia’ four out of five native assigned antepenultimate stress, though. This indicates that the native speakers, subconsciously, prefer antepenultimate stress for words ending in -ia. Some of the second language learners might have picked up on this preference, although two second language learners also wrongly assigned antepenultimate stress to ‘bijutaria’(jewellery). The second language learners are not consistent enough in their output (two assigned antepenultimate stress to ‘grinestia’ and five to ‘balania’) to draw the conclusion that they have acquired the same intuitions as the native speakers. The second language learners in total made 40 mistakes. Out of these mistake eight can be explained by the differences between the Dutch and the Portuguese system. The second language learners used the Dutch system in four cases: ‘raperial’, ‘pirnaz’, ‘altagem’ and ‘grelhador’. In the cases of ‘bijutaria’, ‘balania’ and ‘grinestia’ most second language learners did not (yet) pick up on the Portuguese sub rule that words ending in –ia often get antepenultimate stress; twelve of the mistakes come from these words. On the other hand, the sub rule that words ending in –io often get antepenultimate stress has been noticed by most 35 second language learners; only five of the mistakes come from the words ‘assobio’ and ‘lastario’. The only items where an explanation for their occurrence cannot be found in either of the two systems or in a different manner are the cases of ‘trajeiró’ and futébol. Overall, in 87.3% of all items the Dutch second language learners of Portuguese assigned main stress correctly to the items of the test, whether these were existing words or not. This seems to allow the conclusion that in general these learners have rather good competence in the stress system of Portuguese, i.e. they have come a long way towards acquiring it. In some cases (words ending in –ia and –io) they even showed some subconscious insight into some of the more complicated rules of the Portuguese stress system. As shown in the theoretical background chapter the Dutch and Portuguese stress systems are very similar which might be why the Dutch speakers did so well i.e. they are not many parameters that need to be reset. When they made mistakes they sometimes used the Dutch stress system and sometimes they generalised Portuguese rules to words where they did not apply. 36 6. Conclusion This thesis aimed to bring us a step closer to answering the question whether and if so how Universal Grammar is still available after the critical period. It did so by using a parametric approach to Dutch and Portuguese word stress. Specifically, this thesis dealt with the question whether Dutch beginner to intermediate adult second language learners of Portuguese have developed intuitions, correct or otherwise, regarding the Portuguese stress system. To answer this question a word stress experiment was conducted among second language learners, bilinguals and a native speaker control group. In general, the assumption that the second language learners would not have any difficulty where the two systems are the same was correct. Furthermore, for the items where the systems differed, main stress was often assigned correctly as well. The mistakes that were made were not always due to interference of the Dutch system but sometimes because of over-generalising Portuguese stress rules. Overall, the second language learners show that they have acquired subconscious knowledge of the stress rules of Portuguese although they are not yet able to always apply these rules correctly to each individual case. Apparently these subjects have had sufficient input to deduce the stress rules of Portuguese. This implies that, in overcoming the differences between the Dutch and Portuguese stress systems, parameter resetting may be possible, at least to the limited extent required in this particular case of second language acquisition. The most important limitation of the current investigation lies, no doubt, in the fact that the number of subjects was very small. A group of nine second language learning subjects is small as such, but especially the control group and the bilingual subjects are not significant in size, because of this it is not clear whether disagreement within these groups is due to the small number of subjects or because of trends in Portuguese. Furthermore, the conditions in which the test was conducted were not always ideal; it would have been better if 37 a separate room had been available. The people that passed the hallway might have made the subjects self-conscious or could have caused a distraction influencing the output. Finally, two recommendations. Since the Portuguese stress system is still highly debated it can be recommended to conduct further research in this area. Knowing the correct properties of the target language is essential in order to assess the process of second language acquisition. Moreover, in the current investigation all the second language learners had the same type of education, at the Portuguese programme of the University of Utrecht; it would be interesting to see whether results would be different for groups that acquired Portuguese differently. 38 7. Works Cited Correia, Susanna. The Acquisition of Primary Word Stress in European Portuguese. University of Lisbon. 2009. Web. Fromkin, V., R. Rodman and N. Hyams. An Introduction to Language. 8th Ed. Boston: Thomson Wadsworth, 2007. Print. Kaltenbacher, Martin. Universal Grammar and Parameter Resetting in Second Language Acquisition. Berlin: Peter Lang. 2001. Print Kaye, Jonathan. Phonology, a Cognitive View. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1989. Print. Pater, Joe. “Metrical Parameter Missetting in Second Language Acquisition” Focus on Phonological Acquisition vol. 16, Amsterdam: Benjamins Publishing Company. 1997. 235-262. Web. Strozer, Judith. Language Acquisition after Puberty. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press. 1994. Print. Vigário, Marina. The Prosodic Word in European Portuguese. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 2003. Print White, Lydia. Universal Grammar and Second Language Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 1989. Print Zonneveld, Wim. Phonetics and Phonology Reader (September-November 2010) Department of English Language and Culture Utrecht University. Print 39 8. Works consulted Singleton, David. Language Acquisition: The Age Factor. Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters Ltd. 1989. Print. Thomas, Margaret. Universal Grammar in Second Language Acquisition: A History. London: Routledge. 2004. Print. Trommelen, M and W. Zonneveld. Klemtoon en Metrische Fonologie. Muiderberg: Coutinho. 1989. Print. 40 9. Appendix A. Portuguese test items and their translations. Sentences with existing words: -Durante o concerto a aparelhagem avariou. During the concert the equipment broke. -‘Assobio na noite’ é um conto de Lídia Jorge. ‘Whistle in the night’ is a story by Lídia Jorge. -Durante um teste, barulho não é aceitável. During a test, noise is not acceptable. -Nesta bijutaria têm anéis lindas. This Jewellery has beautiful rings. -Para a minha cozinha nova vou comprar um grelhador. For my new kitchen, I am going to buy a broiler. -‘Legal’ no Brasil significa giro. ‘Legal’ means fun in Brazil. -É necessário comer bacalhau quando se está em Portugal. It is necessary to eat codfish when you are in Portugal. -Qual é a sua opinião sobre tumultos em relação a jogos de futebol? What is your opinion about riots in relation to football? -Há uma mancha no teu pescoço. There is a stain on your neck. -Estou orgulhoso de que terminei o curso de Raperial e Matemática em cinco anos. I was proud of finishing my Raperial and Mathematics studies in five years. -Olá, o senhor poderia dizer me que horas são? Sir, could you tell me what time it is? -Queimei o meu pão na torradeira. I burnt my bread in the toaster. -No verão passado fui frequentemente para praia sem toalha. Last summer I often went to the beach without a towel. -Minha viagem foi arruinada porque me dóia o estômago. My trip was ruined because my stomach hurt. Sentences with nonsense words: -Em uma alna vi um coelhinho que era perseguido por um lobo. In an alna I saw a little rabbit being chased by a wolf. -A cadeira é de madeira e altagem. The chair is made of wood and altagem. -A balania era muita pesada para levantar. The balania is very heavy to lift. -A bicirante foi vendida na loja. The bicirante is being sold in the shop. -Vacas são conhecidas pelas suas manchas, seu leite e cerital. Cows are known for their spots, milk and cerital. -A cor demiante é frequentemente vista como a cor de calças. The colour demiante is often seen as the colour of jeans. -Denator é um ingrediente essencial em certos remédios. Denator is an essential ingredient of certain remedies. -É importante ter uma fidulha na vida. 41 It is important to have a fidulha in life. -Amanhã vou à grinestia com o meu irmão. Yesterday I went to the grinestia with my brother. -Hoje vi um enorme laneito na floresta. Today I saw a huge laneito in the forest. -Quando eu era jovem gostava de ir ao parque e assistir o lastario. When I was young I loved going to the park and watching the lastario. -Estão a falar sobre tirar a grande lintagel da cidade. They are talking about removing the big lintagel of the city. -Lunesto é bom com molho de tomate. Lunesto is good with tomato sauce. -Meratica é mal para a pele. Meratica is bad for the skin. -O governo vai cortar o financiamento de pirnaz. The government is going to cut the finance of pirnaz. -Um plestador nada melhor do que um cavalo. A plestador is better at swimming than a horse. -Estou orgulhoso de que terminei o curso de Raperial e Matemática em cinco anos. I was proud of finishing my Raperial and Mathematics studies in five years. -Um macaco roubou o meu trajeiro, quando eu estava no jardim zoológico. A monkey stole my trajeiro when I was in the zoo. -Fui para casa porque esqueci a minha veraduz. I went home because I forgot my veraduz. -No fundo do oceano existe uma verarem. On the bottom of the ocean there exists a verarem. -Comprei tantas coisas que o verlado não cabe mais no meu saco. I bought so many things that the verlado did not fit in my bag anymore. 42 B. Chart 1b * = one second language learner put stress on the initial syllable