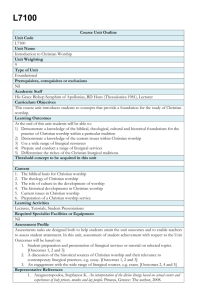

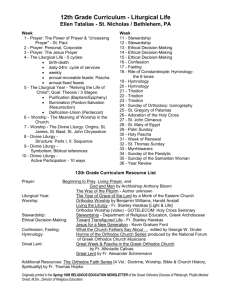

Early Christian Liturgics

advertisement