Chapter Two: The Security Dilemma, Mitigation and Escape

advertisement

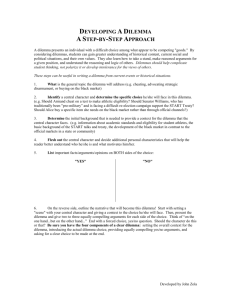

CHAPTER TWO Chapter Two: Theories of Mitigation Introduction Chapter One explored the debate in the academic literature concerning the definition of the security dilemma and the differing approaches to explaining how and why security-seeking states resolve their dilemmas of interpretation and response in a confrontational manner. Although the offensive realist approach to the security dilemma rejects the notion that paradoxical security competition between defensive states can be mitigated, this perspective has been challenged by the defensive realist and constructivist viewpoints on the subject. Literature by defensive realists and constructivists indicate that it is possible for uncertainty in international politics to be reduced, thereby enabling policymakers to rein in paradoxical security competition and thus mitigate the security dilemma. These differing perspectives thus point to an academic debate between offensive realism, defensive realism and constructivism over the extent to which policymakers can attempt to enter into the counter-fears of other states and attempt to reassure others of their peaceful intentions. Chapter Two examines the implications of this academic debate for the possibility of states adopting policies to ameliorate such paradoxical security competition and thus mitigate the security dilemma. In this chapter, I begin by examining the notion of security dilemma sensibility. I then revisit the three theoretical approaches to this thesis – offensive realism, defensive realism, and critical constructivism in an effort to see how they approach the problem of mitigating the security dilemma. 1. Security Dilemma Sensibility Booth and Wheeler coined the term ‘security dilemma sensibility’ to refer to the ability of policymakers to perceive the motives behind, and to show responsiveness towards, the potential complexity of the military intentions of others. In particular, it refers to the ability to understand the role that fear 33 CHAPTER TWO might play in their attitudes and behaviour, including, crucially, the role that one’s own actions may play in provoking that fear.1 When policymakers show security dilemma sensibility, they enter into the counter-fear of other states, acknowledging how their own defensive military postures may have contributed to the fears of others. Under such circumstances, policymakers would be more inclined to seek diplomatic and security postures that assuage the security concerns of other states. Status quo states might, for example, implement Confidence and Security Building Measures (CSBMs) that address the security concerns of others and build trust to mitigate the effects of uncertainty in an anarchic world. 2 Moreover, security dilemma sensibility also requires that policymakers are willing and able to continue implementation of CSBMs with rival states even in the face of opposition from domestic critics as well as regional allies.3 Chapter One explored three distinct theoretical approaches – offensive realism, defensive realism and critical constructivism – in explaining how security dilemma dynamics occur. Given their differing theoretical assumptions, each of these approaches also offers an alternative explanation as to how far policymakers can exercise security dilemma sensibility in their response to the military postures of other states.4 I thus propose to explore the implications of the three theoretical approaches examined in Chapter One for the ability of policymakers to exercise security dilemma sensibility in an anarchic world.5 1 Ken Booth and Nicholas J. Wheeler, The Security Dilemma: Fear, Cooperation and Trust in World Politics (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), p.7. In outlining the notion of security dilemma sensibility, Booth and Wheeler build on John Herz’s 1959 work, International Politics in the Atomic Age, and Robert Jervis’s work, Perception and Misperception in International Politics. 2 This concept was initially coined as ‘confidence-building measures and certain aspects of security and disarmament’ in the Final Act of the ‘Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe’ in Helsinki in 1975 (also known as the Helsinki Accords). See ‘Helsinki Final Act’, http://www.osce.org/documents/mcs/1975/08/4044_en.pdf, accessed 15 May 2006, p.10. 3 Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.5, 7-8. 4 See Appendix 2, ‘Comparison of Offensive Realist, Defensive Realist and Constructivist Approaches to Mitigation of Security Dilemma Dynamics’. 5 Booth and Wheeler caution us against categorising the three logics of insecurity as ‘schools’ of thought. Rather, they refer to these three positions as ‘ideal types’ that describe the ideas held by policymakers. See Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.10-11. 34 CHAPTER TWO 2. Offensive Realism The offensive realist perspective suggests that, because states are never able to distinguish one another’s defensive military capabilities from their offensive ones, uncertainty in international politics is irreducible.6 Faced with the perennial fear of attack, states constantly adopt worst case assumptions in interpreting one another’s intentions and seek to secure their survival through maximising their own power base. Because this dynamic of irreducible uncertainty affects both sides, security-seeking states will constantly fear one another, and envisage a long-term geo-strategic setting based on inescapable security competition. This logic of worst-case thinking will prevail on policymakers even when they are aware of the possibility that their actions may be seen as provocative by the other side. As Barry Posen argued, even if policymakers recognised that their own actions may be seen as threatening, it does not matter if they know of this problem. The nature of their situation compels them to take the steps they do … they must assume the worst because the worst is possible.7 The notion that policymakers adopt worst-case thinking in anarchy is similarly reflected in John Mearsheimer’s articulation of uncertainty as the driving force behind the fatalist logic of insecurity. In The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, Mearsheimer argued that states are constantly uncertain about one another’s intentions, and this uncertainty can never be reduced.8 This, along with the constant fear of attack and the absence of a global Leviathan, means that states constantly adopt worst-case scenario analysis and interpret other states as potential threats. States thus constantly seek military superiority over their rivals as the surest means of self-preservation. Even if they are stronger than their rivals, they fear that they may be overtaken militarily in the future. States thus continue seeking to increase their military advantage. 9 The ambiguous symbolism of weapons can never be reduced. Furthermore, Mearsheimer rejects the notion that states may adopt policies to reassure one another on the grounds 6 John Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics ((New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2001), pp.30-31. 7 Barry Posen, ‘The Security Dilemma and Ethnic Conflict, Survival, 35/1 (1993), p.28. 8 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.30-31; see also Chapter One. 9 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.34-35. 35 CHAPTER TWO that these constitute ‘appeasement’ that is ‘likely to whet ... an aggressor state’s appetite for conquest’.10 Moreover, uncertainty itself can be exploited by aggressive revisionist states. Aggressor-states may claim to have defensive intent to lull their opponents into a false sense of security and thus make them easier to conquer 11 . Given that strategic disinformation and deception have long been instruments of Machiavellian statecraft, Dale Copeland’s observation that ‘when we consider the implications of a Hitlerite state deceiving others to achieve a position of military superiority, we understand why great powers in history have tended to adopt postures of prudent mistrust’ 12 is particularly telling. Thus, if State A assumes that State B is seeking only to enhance its own security, and acts to assuage State B’s fears by unilateral restraint, State A would be making a fatal mistake if State B turns out to be an aggressor.13 Furthermore, Copeland directed our attention to the problem of ‘future uncertainty’ and how this caused policymakers to adopt worst-case scenario thinking in interpreting the intentions of other states. 14 Even when states believe that their rivals are security-seekers, they also have to take into account the possibility of future security threats that might emerge as a result of domestic political developments in other states. 15 Such changes may occur in the form of political succession of new leaders, changing ideologies, or military coups, resulting in the emergence of aggressive, revisionist leaderships, and may occur in spite of a state’s efforts to form a cooperative relationship.16 Failing to prepare for security threats emerging from future uncertainty may prove fatal for a security-seeking state. The benign Weimar Republic, for instance, was replaced by Hitler and the Nazi Party through domestic political developments in Germany.17 This logic was illustrated in a correspondence between Mearsheimer and Alexander Wendt. Mearsheimer argued that Wendt’s argument 10 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.163-64. Copeland, ‘The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism’, pp.202-03. 12 Copeland, ‘The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism’, p.203. 13 Copeland, ‘The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism’, pp.203-04. 14 Copeland, ‘The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism’, p.203. 15 Copeland, ‘The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism’, pp.205-06. 16 Copeland, ‘The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism’, pp.205-06. 17 Copeland, ‘The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism’, p.203. 11 36 CHAPTER TWO cannot predict the future, he (Wendt) cannot know whether the discourse that ultimately replaces realism will be more benign than realism. He has no way of knowing whether a fascistic discourse more violent than realism will emerge as the hegemonic discourse … he would obviously like another Gorbachev to come to power in Russia, but he (Wendt) cannot be sure we will not get a Zhirinovsky instead … defending realism might very well be the more responsible policy choice.’18 At the same time, however, Mearsheimer and other offensive realists qualify their arguments by acknowledging that uncertainty does not always escalate into armed conflict. Policymakers may be forced to recognise the folly of confrontation with a stronger power, and instead engage in temporary cooperation until circumstances favour renewed confrontation.19 Mearsheimer argued that states are not mindless aggressors so bent on gaining power that they charge headlong into losing wars or to pursue Pyrrhic victories. On the contrary … they think carefully about the balance of power and about how other states will react to their moves. They weigh the costs and risks of offence against the likely benefits. If the benefits do not outweigh the risks, they sit tight and wait for a more propitious moment.20 Although states can undertake cooperative actions and enter arms control agreements, the offensive realist perspective underlines that such arrangements are temporary and do not ameliorate the overall pattern of security competition.21 Rather, offensive realist theory emphasises that states, in their pursuit of self-interest in an anarchic world, can never develop compatible security interests beyond the short term. Although states may enter cooperative security arrangements, these are temporary Mearsheimer, ‘A Realist Reply’, International Security, 20/1 (1995), p.92; see also Wendt, ‘Constructing International Politics’, International Security, 20/1 (1995), pp.80-81, and Mearsheimer, ‘The False Promise of International Institutions , International Security, 19/3 (21994-95), pp. 11-12, 43-46. 19 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, p.37. 20 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, p.37. 21 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, p.37. 18 37 CHAPTER TWO arrangements that will inevitably collapse when their interests diverge, leading to renewed security competition. 22 Similarly, the few occasions when states concede power are ‘special circumstances’, pragmatic recognition that they have a limited material capacity for security competition. Their apparently cooperative actions are really aimed at providing themselves with a breathing space to strengthen their own long-term capacity for continuing security competition at a later date. Faced with a stronger adversary, a state may temporarily back away from security competition as a short-term strategy to avoid a conflict which it knows it cannot win, whilst simultaneously planning to undertake long-term mobilisation of its resources for renewed security competition at a later date.23 Thus, for instance, Mearsheimer acknowledged Gorbachev’s adoption of a less confrontational foreign policy and the reduced tensions with the US during the second half of the 1980s. Mearshemer, however, argued that the implementation of ‘New Thinking’ was a pragmatic response to the increasing political and economic cost of security competition with the West. 24 Similarly, Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth argued that Gorbachev’s signing of the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty was not the result of any changed Soviet perspective on security. Rather, this was a desperate response to the material pressures on the USSR resulting from the failure of domestic economic reform. 25 They contend that, as a result of the inefficiency of its centrally planned economic system, the USSR faced a declining capacity for continued security competition against the transatlantic alliance 26 whilst simultaneously retaining control over its satellite states in Eastern Europe.27 Based on this perspective, New Thinking was aimed at freeing more material resources to ‘shift the Cold War into a framework more favorable to the Soviet Union … without placing traditional Soviet interests at risk.’28 22 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.51-53, 158-61, 164-66, Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.164-65. 24 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.201-02, 369-70; Mearsheimer, ‘The False Promise of International Institutions’, p.46. 25 Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth, ‘Power, Globalization and the End of the Cold War: Reevaluating a Landmark Case for Ideas’, International Security, 25/3 (2000), pp.22-25. 26 Brooks and Wohlforth, ‘Power, Globalization and the End of the Cold War’, pp.27-29. 27 Brooks and Wohlforth, ‘Power, Globalization and the End of the Cold War’, pp.22-25. 28 Brooks and Wohlforth, ‘Power, Globalization and the End of the Cold War’, pp.30-31. 23 38 CHAPTER TWO Recent developments in US-Russian relations may be seen to offer further support for the offensive realist perspective. Following the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the USSR, its successor state, the Russian Federation, has formulated an assertive foreign policy. In the post Cold War era, Moscow has used force to retain control of Chechnya, maintained a large nuclear arsenal, and opposed NATO’s expansion into Central and Eastern Europe, as well as NATO’s 1999 intervention in Kosovo.29 More recently, Russia has resumed long-range bomber patrols near NATO airspace, and President Vladimir Putin has suspended observance of its treaty obligations under the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe. 30 Viewed in the wider context of past confrontation between the USSR and NATO, it may be argued that Putin’s adoption of an assertive foreign and security policy is consistent with Mearsheimer’s argument that the security interests of states are never compatible on a long-term basis. The offensive realist perspective thus subscribes to what Booth and Wheeler refer to as the fatalist logic of security competition. Although states can engage in temporary periods of security cooperation, offensive realists argue that these are driven by tactical interest rather than any fundamental change about how policymakers interpret uncertainty in an anarchic world. Faced with a fatalist logic of insecurity, policymakers do not believe that they can move beyond a Hobbesian selfhelp world. It is thus never possible for policymakers to show security dilemma sensibility in their interaction with other states. 3. Defensive Realism As outlined in Chapter One, the defensive realist approach acknowledges that uncertainty in an anarchic world may cause security competition to occur between defensive states. At the same time, however, defensive realists argue that, under certain conditions, it is possible for policymakers to exercise security dilemma ‘Putin warning over US missile row’, BBC, 4 June 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/6717119.stm, accessed on 4 June 2007; Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, p.378. 30 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.378-79; Canadian Forces Press Release, 29 September 2006, http://www.forces.gc.ca/site/newsroom/view_news_e.asp?id=2093, accessed on 15 February, 2008; ‘RAF scrambles to intercept Russian bombers’, The Times, 18 July 2007, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article2093759.ece, accessed on 18 July 2007; ‘Russia suspends arms control pact’, BBC, 14 July 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6898690.stm, accessed on 14 July 2007. 29 39 CHAPTER TWO sensibility. If they can successfully undertaking reassurance whilst simultaneously hedging against the possibility of cheating and continued hostility by the other side, it may be possible to undertake long-term cooperation to reduce uncertainty, build trust, and thus mitigate security dilemma dynamics. The notion that policymakers can, under certain circumstances, determine if other states are driven by fear, rather than hostility, was first examined by John Herz in his 1959 work, International Politics in the Atomic Age. Herz’s revised approach to the security dilemma moved away from the fatalist logic that had guided his writings on the security dilemma in 1950-51. Herz thus wrote that Should it be at all possible to get away from ideological obsessions and view conditions more coolly as involving interests in security, power, and avoidance of all-out war, both sides might even profit from the security dilemma itself, or rather, from facing and understanding it. For, if it is true – as Herbert Butterfield has pointed out – that inability to put oneself into the other fellow’s place and to realize his fears and mistrust has always constituted one chief reason for the dilemma’s poignancy, it would then follow that elucidation of this fact might by itself enable one to do what so far has proved impossible – to put oneself into the other’s place, to understand that he, too, may be motivated by one’s own kind of fears, and thus to abate the fear.31 In other words, policymakers could look past their benign self-images and enter the counter-fears of other states. Moreover, policymakers could act in response to the security fears of others and adopt less threatening military and diplomatic posture. Under such circumstances, security-seeking states could mitigate security dilemma dynamics.32 31 John Herz, International Politics in the Atomic Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959), p.249. Herz’s reference to Herbert Butterfield points to Butterfield’s argument concerning the ‘other minds problem’ faced by policymakers in attempting to enter the counter-fears of other states; see Herbert Butterfield, History and Human Relations (London: Collins, 1951), pp.20-22. 32 Herz, International Politics in the Atomic Age, pp.237-39; see also Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.39-40. 40 CHAPTER TWO Robert Jervis’s work on the deterrence and spiral models further developed the possibility of mitigation. He argued that the spiral model occurred because policymakers ‘do not understand it or follow its prescriptions.’ 33 If, however, policymakers could distinguish between the deterrence and spiral models in interpreting the intentions of other states, they could undertake initiatives to reassure the other side, such as arms control agreements. 34 Over time, reciprocal signals of reassurance would enable both sides to recognise a common interest in security cooperation to reduce uncertainty. The notion that states could respond to spiral dynamics by engaging in selfrestraint to assure one another and thus rein in security dilemma dynamics was explored by Charles Osgood and Amitai Etzioni at the height of the Cold War. Osgood outlined what he called ‘Graduated Reciprocation In Tension Reduction’, or ‘GRIT’, which he described as an ‘arms race in reverse.’ 35 Osgood argued that graduated nuclear disarmament, alongside broader social and economic engagement with the USSR, could be undertaken at minimal cost to US national security. At the same time, through such cooperative measures, Osgood argued that the mutual distrust of the Cold War could be gradually reversed and turned into trust. 36 Similarly, Etzioni proposed a process of nuclear disarmament which he referred to as ‘gradualism’, involving ‘several interdependent steps or grades; the activation of each successive step depending on the success of the preceding ones.’37 As Jervis argued, however, a ‘dominant strategy’ based on the assumptions of the spiral model ran three risks.38 First, strategies like GRIT and gradualism meant the risk of strained alliance relations should an adversary state turn out to have hostile intent. This in turn led to the second danger that Jervis identified. Faced with strained alliance relations resulting from a failed policy of gradualism, a state could feel itself compelled to take a firmer line in a future crisis to reaffirm the credibility of its 33 Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Relations (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), pp.81-82; see also Chapter One. 34 Jervis, Perception and Misperception, pp.81-82. 35 Charles Osgood, An Alternative to War or Surrender (Chicago and London: University of Illinois Press, 1962), pp.86-87. 36 Osgood, An Alternative to War or Surrender, pp.89-93. 37 Amitai Etzioni, The Hard Way to Peace: A New Strategy (New York: Collier Books, 1962), pp.84-85, 134-35. 38 Jervis, Perception and Misperception, pp.109-110. 41 CHAPTER TWO security commitments to its allies. Third, a state’s policy of gradualism could also cause an adversary state to perceive that the first state lacks resolve, is weak-willed and can be bullied into granting more concessions.39 Seen in this light, policymakers who attempt to reassure another state must also be mindful of the possibility that they are instead facing a revisionist state. If the other side does turn out to have hostile intentions, policies of assurance, such as arms limitations and political restraint, may weaken one’s own strategic position against an aggressive state intent on conquest. Jervis thus suggested that policymakers should seek ‘policies that have high payoffs if the assumptions about the adversary that underlie them are correct, yet have tolerable costs if these premises are wrong.’40 Jervis argued that policymakers should focus on acquiring weaponry optimised for defense and deterrence, yet be less effective for offensive purposes.41 Similarly, Thomas Christensen suggested that it was necessary to view security-seeking states as ‘conditional or potential revisionists’, rather than implacably hostile ‘undeterrable ideologues’. 42 Christensen thus argued, against ‘conditional revisionists’, mitigation of security dilemma dynamics was successful through a combination of reassurance and deterrence.43 Jervis further explored the possibility of long-term security cooperation between states attempting to rein in paradoxical security competition in his 1982 article, ‘Security Regimes’. Jervis noted that states could form security regimes consisting of ‘principles, rules, and norms that permit nations to be restrained in their behavior in the belief that others will reciprocate. This concept implies not only norms and expectations that facilitate cooperation, but a form of cooperation that is more than the following of short-run self-interest.’ 44 Regime theory is based on the assumption that actors are rational egoists that prioritise their well-being above that of others. Cooperation is possible when they believe that it serves their long-term 39 Jervis, Perception and Misperception, pp.110-111. Jervis, Perception and Misperception, p.111. 41 Jervis, Perception and Misperception, p.111. 42 Thomas J. Christensen, ‘The Contemporary Security Dilemma: Deterring a Taiwan Conflict’, International Security 25/4 (2002), p.9. 43 Christensen, ‘The Contemporary Security Dilemma’, pp.9-10, 17-19. 44 Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, International Organization, 36/2 (1982), p.357. See also Stephen Krasner, ‘Structural Causes and regime consequences: Regimes as Intervening Variables’, International Organization, 36/2 (1982), pp.185-87. 40 42 CHAPTER TWO interests.45 This is crucial in distinguishing a security regime from offensive realism’s recognition that states are capable of engaging in cooperation with one another. Within the offensive realist worldview, all cooperative arrangements between states are temporary arrangements for short-term advantage. Given the ‘certainty of uncertainty’ 46 in offensive realist theory, there is no possibility for long-term compatibility between the security interests of states. Such security arrangements will thus inevitably collapse after a period of time.47 Jervis, in contrast, emphasised that a security regime goes beyond short-term cooperative arrangements or submission by weaker states bowing to stronger parties. The cooperation entailed in a security regime is based on reciprocal acknowledgement of the legitimate security interests of others in the regime; it is also assumed that the process of security cooperation will continue over the long term.48 Within a security regime, states can adopt restraint in their mutual interaction and observe norms of cooperation in their political and military postures in exchange for reciprocal restraint from other states. By enabling both sides to reach mutually accepted limits on the extent of their competition for security, states could thus achieve a satisfactory level of security for themselves without undermining the security of others.49 Jervis notes four conditions that have to be met if a security regime is to succeed: first, states have to prefer an ordered, stable political environment over coercion and threats of war. Second, states also have to believe that other states share their preference for mutual security and cooperation; if either side believes that the other has hostile intent, long-term security cooperation is not possible. Third, states have to believe that their security can be achieved without undermining the security of others. Fourth, states have to view war as an unacceptably costly means of achieving security.50 Successful fulfilment of these conditions enables states to develop norms of long-term reciprocal security cooperation. Although states remain rational egoists Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, pp.358-59; see also James D. Morrow, ‘The Ongoing Game Theoretic Revolution’, in Manus I Midlarsky (ed.), Handbook of War Studies II (Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press: 2000), pp.164-76. 46 Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, p.37. 47 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.51-53. 48 Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, p.357. 49 Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, p.360. 50 Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, pp.359-62. 45 43 CHAPTER TWO in seeking their security, they are able to do so without simultaneously undermining the security interests of others. As Jervis noted, however, security regimes are not possible when states perceive their security interests as incompatible. 51 Even after compatible security interests allow a security regime to be formed, the regime could nonetheless collapse if parties to it believe that their interests are moving apart. It is conceivable that states may enter a security regime, only to have their interests diverge at a later date. This would cause states to calculate that remaining within the regime would no longer serve their interests, leading to renewed security competition. 52 Thus, in acknowledging the possibility of long-term cooperation to reduce tensions, a security regime can be seen as providing a limited basis upon which policymakers can exercise a mitigator logic of insecurity. Because security regimes are based on the notion that states are rational egoists, states will still view one another as potential competitors. The strengths and weaknesses of security regimes were illustrated by Jervis’s examination of the Concert of Europe. Jervis noted that, in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, the European powers did not seek to maximize their individual power positions, they did not always take advantage of others' temporary weaknesses and vulnerabilities, they made more concessions than they needed to, and they did not prepare for war or quickly threaten to use force when others were recalcitrant. In short, they moderated their demands and behavior as they took each other’s interests into account in setting their own policies.53 Jervis argued that such cooperation led to the adoption of a broader understanding of security in which other members of the Concert were viewed as partners. Moreover, the adoption of norms of restraint in the expectation of long-term reciprocation indicated an acknowledgement of common interests in reducing Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, pp.359-62. Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, pp.359-62. 53 Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, pp.362-65; quote on pp.362-63. 51 52 44 CHAPTER TWO uncertainty. States thus undertook diplomatic restraint because they recognised that the Concert offered long-term benefits for their own security. Although the Congress of Europe did not abolish conflict, it managed to contain the pursuit of realpolitik, enabling all the major European powers to achieve a sufficient level of security in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars.54 At the same time, however, Jervis acknowledged that the Concert of Europe did not last. The cooperation and diplomatic restraint during the early years of the Concert had been based on its members’ expectation that the regime would survive, and therefore provide them with an incentive to maintain it. By 1823, with the memories of the Napoleonic Wars fading, the European powers began facing a decreased incentive in maintaining the Concert. 55 Booth and Wheeler thus refer to the Concert of Europe as ‘a controversial case for mitigator thinking about the security dilemma … its demise … lends support to the rational egoist argument that the norms were temporary coincidences of interest.’56 Jervis similarly rejected the notion that the period of US-Soviet détente could be seen as a security regime. Although the US-Soviet summit in Moscow in May 1972 and the Strategic Arms Limitations (SALT I) Agreement adopted the rhetoric of long-term security cooperation 57 , Jervis emphasised that these did not constitute a regime as both sides were driven by short-term self-interest. Moreover, Moscow and Washington had differing conceptions of security. Although President Nixon and Secretary of State Kissinger had advocated détente in the hope that the USSR would adopt a more restrained foreign policy, the Soviet leadership evidently saw no contradiction between an agreement on strategic restraint and nuclear arms control, and continued competition for influence in the Third World. 58 This was further compounded when conservative US policymakers formed the Committee on the Present Danger (CPD) that argued for the adoption of a firm posture of deterrence against the USSR.59 Booth and Wheeler used the term ‘ideological fundamentalism’ to refer to the CPD’s belief that the USSR was a hostile entity as the result of its political identity as an ideologically antagonistic communist regime. These developments represented growing perception in Washington and Moscow that their Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, pp.362-65. Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, p.368. 56 Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.113-14. 57 Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, pp.371-72. 58 Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, pp.372-73. 59 Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.120-21. 54 55 45 CHAPTER TWO security interests were incompatible, leading to the collapse of détente. This was illustrated by the development of a new generation of nuclear missiles by the US and the USSR, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the election of Reagan on an aggressively anti-Soviet platform in 1980.60 The difficulties states face in establishing and maintaining security regimes against the pressures of uncertainty is evident in the two broad approaches to mitigation that have been developed based on the assumptions of defensive realism. The first approach is derived from Jervis’s work on Offense-Defense Theory (ODT) and focuses on the development of defensive weaponry, doctrine and force postures as a means of reducing the symbolic ambiguity of weapons. As outlined in Chapter One, ODT evaluates the extent of stability in a given security dilemma dynamic based on two variables, the Offense-Defense Balance (ODB) and Offence-Defence Differentiation (ODD). 61 Jervis argued that a ‘fourth world’ where the ODB is defence-dominant, and where defensive military postures can be clearly distinguished from offensive ones, offered the best possibility for mitigating security dilemma dynamics. Because the ODB favours defensive weaponry and military postures, both sides would find it difficult to successfully conquer one another, and thus face a disincentive in attacking first. At the same time, it is possible for both sides to adopt military postures that are clearly defensive. Such a situation is ‘doubly stable’62 as it allows security-seeking states to achieve a sufficient level of security for themselves without inadvertently threatening others. Charles Glaser further developed Jervis’s work on ODT and argued that under certain circumstances, defensive states can signal their peaceful intent towards one another. When offensive military postures can be clearly distinguished from defensive ones, states that acquire offensively-oriented weaponry and develop offensive military doctrine signal offensive intent. 63 Under such circumstances, there would be no security dilemma as the state acquiring such military capabilities has offensive intent and is a security challenge that has to be deterred or defended against. In contrast, 60 Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.122-23. See Chapter One for my discussion of Jervis’s first, second and third worlds. 62 Jervis, ‘Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma’, World Politics, 30/2 (1978), p.214. 63 Charles Glaser, ‘Political Consequences of Military Strategy’: Expanding and Refining the Spiral and Deterrence Models’, World Politics, 44/4 (1992), pp.503-05, 508-510, 528-32.; Glaser, ‘Realists as Optimists: Cooperation as Self-Help’, Security Studies 5/3 (1996), pp.133-43. 61 46 CHAPTER TWO Glaser argued that security-seeking states are likely to consider what kinds of weaponry are most effective in enhancing deterrence, and if deterrence fails, defence. Such states can also ask themselves what military capabilities are less threatening to the defences of other states. 64 If the ODT variables favour Jervis’s ‘doubly safe’ fourth world, defensive states can achieve a satisfactory level of security for themselves by concentrating on the acquisition of defensively-oriented weaponry, whilst foregoing the acquisition of offensively-oriented armaments. 65 Thus, when defensive military postures are advantageous, security-seeking states can signal their defensive intent. Given that the ODB is defense-dominant here, the adoption of defensive strategies becomes a more effective means of achieving one’s security. Defensive states can agree to arms control measures that limit or eliminate offensive weapons and thus sacrifice their ability to attack one another.66 The circumstances under which status quo states can signal defensive intent was further explored by Evan Braden Montgomery. Arguing that few states have successfully reassured one another through their force postures, Montgomery directed our attention to the difficult trade-offs that benign states face in attempting to reassure one another. He argued that, even if defensive military postures could be distinguished from offensive ones, reductions in a state’s ability to attack will also decrease its ability to defend, and gestures sufficient to communicate benign preferences will increase its vulnerability to possible aggressors … the same actions necessary to reassure their adversaries will also endanger their own security if those adversaries are in reality aggressive.67 Faced with the belief that the other side may be a hostile state, policymakers are reluctant to initiate significant concessions to one another (such as large arms cutbacks) for fear that the other state may not reciprocate. Furthermore, a state willing Glaser, ‘Realists as Optimists’, pp.133-43. Glaser, ‘Realists as Optimists’, p.134. 66 Glaser, ‘Realists as Optimists’, p.142; Glaser, ‘When Are Arms Races Dangerous? Rational versus Suboptimal Arming’, International Security, 28/4 (2004), pp.52-53. 67 Evan Braden Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma: Realism, Reassurance, and the Problem of Uncertainty’, International Security, 31/2 (2006), pp.153-54. 64 65 47 CHAPTER TWO to make a large arms reduction runs the risk of domestic political criticism as well as fears of alliance abandonment from key allies. Thus, although such a large concession may be necessary if trust is to be built, it may also be rejected if policymakers view domestic political consensus and alliance relations as more important. Conversely, a state may choose to send smaller cooperative actions that do not affect its military capabilities or that arouse domestic or allied criticism. However, such smaller gestures are likely to be dismissed by the other side as a superficial gesture that contributes little or nothing to trust-building.68 Montgomery expanded on Jervis’s ODT and argued that it was necessary to consider a third possible set of conditions to the ODB in addition to the defensedominant and offense-dominant worlds that Jervis examined in ‘Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma’. Montgomery argued that both the offense-dominant and defense-dominant worlds hindered successful signalling of peaceful intent. Under conditions that favoured offensive weaponry, small reductions in offensive forces would limit a state’s ability to use force against other states and thus be sufficient to reveal benign intent.69 At the same time, however, given the strength of offense over defense, even small reductions in offensive weapons would leave a state with little to fall back on should another state develop hostile intent.70 Montgomery also argued that, although a defense-dominant ODB contributed to stability, reassurance also became more difficult. Although small reductions in weaponry were possible given the strength of defense, they would also do little to reassure the other side. Conversely, although a large reduction in defense-dominant weaponry would enable securityseeking states to reassure one another, such reductions would also severely undermine their most effective means of defense, and would thus be rejected by policymakers. 71 Montgomery thus argued that, apart from the ability to clearly distinguish defensive military postures from offensive ones, successful signalling of peaceful intent also depended on a ‘neutral’ ODB in which offense and defense were equally strong.72 Under these conditions, defensive states could reduce enough of their material capabilities to reassure one another, whilst simultaneously retaining sufficient Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, pp.153-54 Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, p.165. 70 Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, p.166. 71 Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, p.166. 72 Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, p.167. 68 69 48 CHAPTER TWO weapons to provide an effective defensive or deterrent capability should the other side turn out to be hostile.73 A second defensive realist approach to cooperation examines the prospect for a gradual process of building trust and reducing mutual uncertainty and hostility between adversarial states. Andrew Kydd critiqued GRIT and gradualism on the grounds that such strategies did not pay sufficient attention to the problem of mistrust. Given a backdrop of mutual hostility and suspicion, there was little reason why adversarial states would want to reassure one another.74 Furthermore, Kydd criticised the notion that GRIT should entail minimal cost for a state attempting to signal reassurance. Given that such a signal would involve little material concession, it was more than likely that the other side would dismiss it as ‘mere talk’ and remain suspicious.75 As Kydd argued, ‘gestures with little risk attached will be dismissed as feints by the other side and will not change beliefs.’76 Kydd defined trust as ‘a belief that the other side prefers mutual cooperation to exploiting one’s cooperation … to be trustworthy, with respect to a certain person in a certain context, is to prefer to return their cooperation rather than exploit them.’77 Kydd argued that mitigation of security dilemma dynamics depended on countering the underlying mistrust between states. Faced with high levels of mistrust, he argued that it was necessary for states to undertake ‘a signal that is so costly that the untrustworthy type finds it too risky to mimic.’78 As untrustworthy states do not place the same value on cooperation as trustworthy states, they are thus unwilling to take risks in building trust and would not engage in the process of costly signalling.79 In contrast, a trustworthy state would place a higher value in cooperating to reduce tension and would be prepared to take greater risks to its own security. A trustworthy state would be willing to unilaterally undertake signals costly enough to its own Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, pp.166-67 Andrew Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), pp.184-85. 75 Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, pp.184-85. 76 Kydd, ‘Trust, Reassurance and Cooperation’, International Organization, 54/2 (2000), p.326. 77 Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, pp.6, 8-9. 78 Kydd, ‘Trust, Reassurance and Cooperation’, p.326. 79 Kydd, ‘Trust, Reassurance and Cooperation’, p.326. 73 74 49 CHAPTER TWO security in order to reassure the other side, such as large arms reductions. 80 At the same time, such signals must not be too costly, lest they are seen by domestic critics as ‘appeasement’ of a hostile state, or if such signals undermine a state’s ability to defend itself should the other state turn out to have hostile intent. 81 Moreover, trustworthy states can sustain the process of costly signals even in the absence of immediate reciprocal cooperation from the other side.82 Both of these approaches to mitigation contribute to an explanation of the failure by both Washington and Moscow to reassure one another from the 1950s to the 1970s. More importantly, both Montgomery and Kydd directed our attention to the circumstances that enabled both sides to successfully reassure one another from the mid-1980s onward. Montgomery argued that Khrushchev’s attempts to reassure the US by offering to reduce Soviet conventional forces failed to convince the Eisenhower administration because the Soviet nuclear arsenal continued to expand during this period. Because both sides had the ability to devastate one another with nuclear weapons, defence through nuclear deterrence was strong. At the same time, however, given the then-prevailing view that war would be fought with nuclear weapons, this meant that neither side believed that it was possible to defend themselves without nuclear weapons. Thus, the conventional force reductions that Khrushchev undertook did not reassure the US.83 Moreover, Kydd notes that although Brezhnev initiated tentative offers of cooperation, such as the 1972 Moscow Summit and the Strategic Arms Limitations (SALT) Talks, these did not assuage US fears over the possibility of Soviet defection from cooperation as Brezhnev was seen as ‘untrustworthy (and) … interested in exploiting the West.’ 84 Statements from the USSR calling for peace and cooperation were seen by the US as ‘cheap talk’ at best, or deliberate disinformation at worst.85 In contrast, however, Gorbachev undertook a different approach, known as ‘New Thinking’, to build trust. According to Kydd, Gorbachev recognised that limited Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, p.198; Kydd, ‘Trust, Reassurance, Cooperation’, p.326. 81 Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, p.198. 82 Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, p.187. 83 Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, pp.174-77. 84 Kydd, ‘Trust, Reassurance and Cooperation’, p.342. 85 Kydd, ‘Trust, Reassurance and Cooperation’, p.326. 80 50 CHAPTER TWO initiatives were not seen as sincere by the US. The Soviet leader realised the necessity of undertaking measures that were ‘costly’ enough to address US mistrust of the USSR. This was evident following the 1986 Reykjavik Summit when Gorbachev proposed a process of comprehensive nuclear disarmament, beginning with the elimination of the USSR’s SS-20 Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs).86 The Reykjavik Summit failed to produce any agreement due to the Reagan Administration’s reluctance to abandon the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), 87 causing conservative policymakers in Moscow to advocate confrontation against the US.88 Yet, despite the unsuccessful outcome of the Reykjavik Summit, in February 1987, Gorbachev announced his willingness to eliminate Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) without linkage to SDI.89 The INF Treaty may be seen as a costly signal from Gorbachev for several reasons. First, de-linkage of SDI from the INF Treaty meant that the USSR was effectively surrendering its sub-strategic nuclear arsenal, even whilst the US SDI program threatened to neutralise the strategic importance of Soviet nuclear weapons. Secondly, by agreeing to deactivate disproportionately more nuclear warheads than the US, Gorbachev’s acceptance of the INF Treaty indicated that some level of risk to Soviet security was necessary to build trust with the US.90 Third, by agreeing to a highly intrusive verification regime to ensure compliance with the treaty, Gorbachev accepted a level of transparency that the US had considered unthinkable under Brezhnev. Furthermore, Montgomery argued that the INF Treaty was successful in building trust with the US because Gorbachev was in a position to eliminate Soviet weapons that NATO found offensive, its SS-20 IRBMs, whilst retaining sufficient material capabilities for credible deterrence in the form of its Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) and Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs).91 In other words, Gorbachev had a margin of safety within which he could make significant concessions to the US whilst building trust. 86 Raymond L. Garthoff, The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War (Washington DC: The Brookings Institution, 1994), pp.287-88. 87 Garthoff, The Great Transition, pp.288-89. 88 Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.150-51. 89 Garthoff, The Great Transition, p.305; The INF Treaty itself was signed in December 1987 90 Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, p.228. 91 Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, pp.181-82. 51 CHAPTER TWO These actions led to a debate within the Reagan administration about Soviet intentions. Although National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft remained suspicious of Soviet intentions,92 by late 1987, Reagan and Secretary of State George Schultz began to acknowledge the possibility that Gorbachev sought a more cooperative foreign policy with the US.93 At the same time, however, Sarah Mendelson noted that, following the unsuccessful outcome of the Reykjavik Summit, the Soviet leader had recognised that the Reagan administration would not consider ‘New Thinking’ credible as long as the USSR remained involved in the Afghan War.94 In February 1988, Gorbachev announced that Soviet forces would be withdrawn from Afghanistan.95 In 1988, Reagan, in a sharp departure from the confrontational posture that had defined the early years of his administration, visited Moscow and referred to his previous Cold War rhetoric of antagonism as ‘another time, another era’. 96 Gorbachev’s December 1988 speech at the UN can be seen as another costly signal. In his speech, the Soviet leader announced the unilateral withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet troops, including six tank divisions, from the USSR’s satellite states in Eastern Europe.97 Kydd notes that this costly signal went beyond Gorbachev’s tentative peace feelers in 1985-86, as the size of the proposed troop reduction could have been verified. The extent of this costly signal thus undermined the claims by conservative policymakers in Washington that ‘New Thinking’ was ‘cheap talk’ or a ‘propaganda device’.98 The events of 1989 saw further costly signals from Gorbachev. His predecessors, Khrushchev and Brezhnev, had shown their willingness to use force to suppress political dissent in the USSR’s satellite states in Eastern Europe. In contrast, in April 1989, Gorbachev explicitly ruled out the use of force against political dissent Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, p.179. Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, p.229; Garthoff, The Great Transition, pp.318325. 94 Sarah Mendelson, ‘Internal Battles and External Wars: Politics, Learning and the Soviet Withdrawal From Afghanistan’, World Politics, 45/3 (1993), p.356, cited in Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, p.230. 95 Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, p.232. 96 Garthoff, The Great Transition, p.352. 97 Mikhail Gorbachev, ‘Speech to the 43rd General Assembly Session of the United Nations’, 7 December 1988, accessed on 16 May 2006 at http://edition.cnn.com/SPECIALS/cold.war/episodes/23/documents/gorbachev/ 98 Kydd, ‘Trust, Reassurance, Cooperation’, pp.230-31, 348; Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, p.152; Garthoff, The Great Transition, p.352. Although some quarters in Washington remained suspicious of Gorbachev in 1988, Reagan had, by this time, come to acknowledge Gorbachev’s commitment to building trust with the US and ending the confrontation of the Cold War. 92 93 52 CHAPTER TWO in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev’s non-intervention to suppress the Velvet Revolution in the autumn of 1989, as well as the concurrent move toward demokratizatsia within the Soviet political system, effectively repudiated the ‘Brezhnev doctrine’ and again indicated the extent of Gorbachev’s commitment to a new course of policy.99 These arguments point to the mitigator logic of insecurity identified by Booth and Wheeler. Although the US and Soviet Union remained in a condition of anarchy, it was also possible for Moscow to adopt defensive military postures to signal defensive intent and thus reassure the Reagan Administration. Defensive states can reassure one another by reducing offensive military capabilities such as tank divisions (and, in the case of Gorbachev and the end of the Cold War, IRBMs) thus indicating the extent of risk they were prepared to take to mitigate security dilemma dynamics, whilst retaining sufficient forces for defence, such as ICBMs and SLBMs. Such cooperative security arrangements between rival states may be seen as examples of security regimes, platforms for trust-building that go beyond the short-term pursuit of self-interest. By providing states with arrangements that meet their common interests in security cooperation, security regimes enable states to move away from the fatalist logic of insecurity and mitigate security dilemma dynamics. At the same time, however, it is necessary to emphasise that, under defensive realism, mitigation of security dilemma dynamics is based on the notion that states are rational egoists with fixed interests in security. Although security regimes can lead to long-term security cooperation, its sustainability has to be qualified, as a security regime may also collapse. If states believe that the regime no longer serves their security interests, it is likely that they will abandon it and return to power politics, arms racing and security competition. As Jervis argued, because the interests of the European powers began to drift apart from 1823 onwards, the Concert of Europe was gradually undermined. 100 Furthermore, the arguments outlined by Montgomery and Kydd indicate the importance of optimal material conditions for states to successfully reassure one another. 99 Kydd, ‘Trust, Reassurance, Cooperation’, p.349. Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, p.368. 100 53 CHAPTER TWO Montgomery’s argument indicated the difficulty of reassurance in both the offence-dominant and defence-dominant worlds. He argued that Gorbachev was in a ‘unique position’ because ‘he was able to reduce [conventional] forces that posed a significant threat to his adversary, while retaining different [nuclear] forces that preserved his state’s security.’ 101 Whether such optimal material conditions can be replicated in other instances of security dilemma dynamics is open to debate. Similarly, the costly signals that Gorbachev undertook contributed to the decline and collapse of the USSR. The extent to which policymakers elsewhere are prepared to risk regime collapse is thus open to question. Had Gorbachev foreseen the collapse of the Soviet Union, it is open to debate if he would have been willing to run the risks that he had taken in the implementation of New Thinking. Seen in this light, the difficulties in sustaining a security regime underline its limitations and potential for collapse. Moreover, as security regimes are based on the assumption that states are rational egoists with fixed interests in security, it is not possible for policymakers to transcend uncertainty in international politics. States will continue to base their security on the assumption that they will retain sufficient material capabilities with which they can defend themselves. States in a security regime will have only limited offensive military capabilities and thus face reduced symbolic ambiguity behind one another’s weapons. At the same time, however, such weapons can still be used offensively, albeit with less effectiveness. Under the defensive realist approach, it is thus not possible for policymakers to transcend uncertainty in international politics. 4. Constructivism The constructivist approach to mitigation focuses on how the socially constructed antagonistic images that states have of another can be reinterpreted. The Hobbesian logic of anarchy may have caused policymakers to adopt a fatalist logic of insecurity in interpreting the intentions of other states. Given that antagonistic relationships are social constructs, however, it is also possible for policymakers to examine their assumptions about other states, consider the possibility that their own military postures may be seen as threatening by the other side, and thus reinterpret the meaning of their relationship. If policymakers can enter into one another’s counterfears, they may interact with one another based on a Lockean intersubjective identity 101 Montgomery, ‘Breaking Out of the Security Dilemma’, p.183. 54 CHAPTER TWO instead.102 Security dilemma dynamics can thus be mitigated. Furthermore, states may reinterpret their images of one another and acknowledge the indivisibility of peace in their relationship. Under such circumstances, uncertainty in international politics can be transcended.103 The possibility that states in an antagonistic relationship can attempt to enter into the counter-fears of their adversaries has been examined by Alistair Iain Johnston, Roland Bleiker and J.J. Suh. In his analysis of US-Chinese security dilemma dynamics104, Johnston rejects the notion that Washington and Beijing have a static conception of their interests. Rather, he argues that these interests appear to be fixed because repeated US-Chinese interactions based on shared understandings of antagonism. As such hostile images of one another dominated the political discourse between Washington and Beijing during the 1990s, the antagonistic relationship between the US and China became further internalised. 105 Such interactions have caused both sides to believe that they have incompatible security interests in their relationship. As Johnston wrote, ‘security dilemmas create features of a Hobbesian anarchy … it is necessary to view security dilemmas as social interactions – socializing experiences.’ 106 Seen in this light, Johnston rejected the notion that paradoxical security competition between the US and China is inevitable.107 Johnston argued that if US and Chinese policymakers could acknowledge the ‘political, societal, and ideational implications of treating others as adversaries’,108 it would be possible for them to recognise the socially constructed nature of their antagonistic relationship. The constructivist approach to entering into the counter-fears of other states was further developed by Bleiker. In his study of socially constructed identities on the Korean peninsula, Bleiker argued that the traditional conception of security, with its focus on military power and deterrence, has caused further internalisation of the 102 Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p.283. 103 Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, p.297. 104 This use of ‘security dilemma dynamics’ is derived from this thesis’s understanding of the term. 105 Alistair Iain Johnston, ‘Beijing’s Security Behavior in the Asia-Pacific: Is China a Dissatisfied Power?’, in JJ Suh, PJ Katzenstein and A Carlson, Rethinking Security in East Asia (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), p.80. 106 Johnston, ‘Beijing’s Security Behavior in the Asia-Pacific’, p.80. 107 Johnston, ‘Beijing’s Security Behavior in the Asia-Pacific’, p.81. 108 Johnston, ‘Beijing’s Security Behavior in the Asia-Pacific’, p.82. 55 CHAPTER TWO images of antagonism and hostility between Pyongyang and Seoul. 109 Against this backdrop, Bleiker argued that South Korea’s ‘Sunshine Policy’ could be seen as a rethinking of security. By encompassing a dialogue based on peace and the acceptance of political differences between North and South Korea, the Sunshine Policy involved a process of social transformation. 110 Bleiker thus argued that a dialogue of peace could enable ‘a new, more pluralistically defined vision of identity and unity that may one day replace the present, violence-prone demarcation of self and other.’111 Similarly, Suh wrote that mitigation of the security dilemma was possible ‘when both sides recognize the interactive nature and social underpinnings of the dilemma. A possible solution lies in a set of measures that address the security concerns of both within a single framework.’ 112 Suh thus cited South Korea’s Sunshine Policy as an attempt by Seoul to enter into the counter-fears of Pyongyang. Suh argued that, because Seoul appreciated the possibility that the DPRK’s nuclear and missile programs were driven by its fear of the US, South Korea avoided a confrontational response to the North Korean missiles tests of July 2006. 113 Suh thus argued that A way out of the dilemma … starts with an understanding that the North Korean threat and the US threat are mutually constitutive. This requires underscoring the social aspects of the security dilemma, rather than treating the dilemma … simply as insecurity spirals … Needed are not just institutional measures that constrain state behavior, but also social steps that contribute to a transformation of the social reality between the countries.114 109 Roland Bleiker, Divided Korea: Toward a Culture of Reconciliation (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), pp.17-24. 110 Bleiker, Divided Korea, pp.xxxii-xliv, 64, 70-75. 111 Bleiker, Divided Korea, p.100. 112 Suh, ‘Producing Security Dilemma out of Uncertainty: The North Korean Nuclear Crisis’, Mario Einaudi Centre for International Studies (2006), p.4. 113 Suh,, ‘Producing Security Dilemma’, p.31. 114 Suh, ‘Producing Security Dilemma’, p.30. 56 CHAPTER TWO In outlining a constructivist approach through which states can attempt to enter into the counter-fears of others, the arguments outlined by Johnston, Bleiker and Suh supplement Wendt’s theory of social learning. Wendt argued that states can undertake social acts through which they learn more about one another’s identity, thereby enabling them to reinterpret the meaning of their relationship and acknowledge that other states arm out of fear, rather than hostility. Thus, a security paradox that has emerged between two defensive states as a result of socially constructed hostility can be overcome if they receive new information and interpretations about one another’s intentions. Social learning makes it possible for an existing Hobbesian intersubjective identity to be gradually reinterpreted and replaced by a Lockean one, enabling states to view one another as rivals rather than enemies.115 Given Wendt’s argument that ideas and interests are mutually constitutive, such conditions would point to change in the interests of states. As states in a Hobbesian relationship assume that they are facing a hostile other, military security is their priority interest. In contrast, within the Lockean logic of anarchy, rivalry between entities in a given anarchic system is still possible, but not to the extent of them casting each other as potential enemies. Although states still worry about their security, they are not confronted with imminent threats to their own survival. Seen in this light, it may be argued that the perspectives outlined by Johnston, Bleiker and Suh point to a process of social learning. States facing security dilemma dynamics can acknowledge that their own actions may have contributed to the other’s social construction of their antagonistic relationship. Moreover, in recognising that their antagonism has been mutually constituted, policymakers may also attempt to move away from confrontation and toward cooperation. This move away from a Hobbesian logic of anarchy to a Lockean one thus indicates a changed conception of their interests. Under these circumstances, security dilemma dynamics can be mitigated.116 Social learning can continue within the Lockean logic. Even if the norms of cooperation have been internalised, new information between states may cause them to reinterpret their relationship as hostile. Under such circumstances, states are likely 115 116 Wendt, Social Theory of international Politics, pp.328-36. Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, pp.283-96. 57 CHAPTER TWO to return to the Hobbesian logic and renewed security competition. 117 At the same time, however, further social acts may lead to gradual internalisation of a Kantian logic of anarchy based on a role structure of friendship instead. States may come to view one another as friends, with whom war and rivalry are no longer seen as plausible forms of interaction. 118 Wendt compared such a situation to the notion of a ‘security community’ outlined by Karl Deustsch. 119 Although anarchy remains in international politics, states no longer fear insecurity as they now have shared understandings of the peaceful intentions of one another. Under these circumstances, states will have transcended security competition in international politics.120 Karin Fierke acknowledged that Wendt provided a theoretical discussion of the intersubjective character through which the images that states have of each other is constituted. At the same time, however, Fierke critiqued Wendt for not applying his theory to his analysis of Gorbachev’s adoption of New Thinking and the end of the Cold War. 121 Wendt’s approach, she argued, does not explain how identities are constituted, or how they may be reconstituted and changed.122 As Fierke points out, it is as if Gorbachev develops something of ‘private language’, his ‘new thinking’, which he then presents to the world. But this is contrary to the constructivist principle that ‘meanings in terms of which action is organised arise out of interaction’. Based on this principle, we should expect not that Gorbachev engages himself in a process of rethinking but that he engages in a process with others.123 In seeking to address this issue, Fierke directs our attention to how repeated interactions of hostile dialogue contribute to the construction of a Hobbesian logic of anarchy. When an intersubjective identity has been constructed as antagonistic, states 117 Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, pp.294-96. Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, pp.297-299. 119 Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, pp.299-300. 120 Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, pp.299-301; see also Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma (2008), pp.296-97. 121 Karin M. Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies: Critical Investigations in Security (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), p.60. 122 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, p.60. 123 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, p.60. 118 58 CHAPTER TWO define their interests as being based on security against an antagonistic other. At the same time, however, Fierke notes that, within the context of international relations, it is possible for two or more different dialogical approaches to co-exist at the same time, and that these give meaning to different possible forms of interaction between states.124 An existing ‘hostile interaction’ based on nuclear arms-racing to strengthen deterrence may thus be reinterpreted as one that increased the risk of inadvertent nuclear war.125 Repeated interactions based on reassurance and peace can thus give increased meaning to a cooperative relationship and reduce tension and hostility.126 Seen in this light, dialogue between policymakers may be seen as a process through which identities and interests can change. By assigning new meanings to one another in their dialogue, policymakers can revise their assumptions about one another and attempt to enter into the counter-fears of others. Under such conditions, it may become possible for them to develop new identities of one another.127 Recalling the mutually constitutive nature of identity and interests within the constructivist perspective of international politics, the emergence of new identities also means that states will reinterpret the meaning of their interests in their relationship. In Changing Games, Changing Strategies, Fierke argued that dialogue was a process of social transformation that broke down the constructed barriers of the Cold War. She thus defined dialogue as ‘a reciprocal exchange through both parties grow and change … the meaning of words, knowledge of one another’s position and the stakes of the relationship … constitute dialogue’128 through which intersubjective identities could be transformed. Similarly, in Diplomatic Interventions, Fierke wrote that dialogue enabled both sides in a confrontational relationship to step back from the conflict and to articulate their separate stories of suffering … an effort is made to disentangle various assumptions about the other … through a process of structured dialogue parties 124 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.21-22, 62-63. Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.16-26. 126 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.62-64; Fierke, Diplomatic Interventions: Conflict and Change in a Globalizing World (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), pp.174-79. 127 Fierke, Diplomatic Interventions, pp.146-52. 128 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.135-37. 125 59 CHAPTER TWO will begin to put themselves in the shoes of the other and to reframe both the conflict and the potential solution.129 The constructivist approach to mitigation of security dilemma dynamics was illustrated in Fierke’s examination of Gorbachev’s ‘New Thinking’ and the end of the Cold War. Fierke directs our attention to how dialogue between Gorbachev and Reagan built trust and enabled Moscow and Washington to overcome the confrontation of the Cold War. 130 Thus, despite the past decades of Cold War confrontation and mutual hostility and suspicion, it became possible for both Reagan and Gorbachev to contemplate interaction based on trust. Although his predecessors had repeatedly blamed the US for the nuclear arms race, Gorbachev instead demonstrated security dilemma sensibility by acknowledging that Soviet actions had contributed to the political tensions of the Cold War.131 Gorbachev’s peace feelers at the Reykjavik Summit may be seen as the beginning of a dialogue that sought cooperation in addressing a shared concern, namely, nuclear disarmament and building trust, thereby challenging the thendominant discourse of mutual mistrust and nuclear deterrence. 132 Although the Reykjavik Summit failed to produce a result in arms control, Fierke argued that the ‘human touch’ embodied in the Soviet leader’s move away from confrontation gave meaning to a more friendly relationship with Reagan. 133 Furthermore, Gorbachev continued to reassure Washington the following year with the signing of the INF Treaty, thus increasing the meaning of a cooperative relationship with the US. By eliminating the class of nuclear missiles to which NATO had assigned a hostile meaning, Soviet behaviour under Gorbachev reflected to the US a new, friendly relationship that ran contrary to the ‘aggressive Soviet Union’ of the past. 134 By breaking away from past Soviet behaviour and constant cheating in past attempts at cooperation, Gorbachev’s New Thinking gave increasing meaning to a new basis for 129 Fierke, Diplomatic Interventions, p.148. Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.146-51; Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.147-48. 131 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.126-27, Booth and Wheeler The Security Dilemma, pp.149-50. 132 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, p.92. 133 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.125-26, 150. 134 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.158-60. 130 60 CHAPTER TWO interaction which allowed for cooperation and trust between the US and USSR.135 NATO’s past image of the USSR as a security threat to be deterred began to give way to a new identity of Gorbachev as a peacemaker who sought to end the confrontation of the Cold War. Under these circumstances, US and NATO interests in security became gradually reinterpreted.136 The constructivist perspective thus suggests that security dilemma sensibility refers to the ability of policymakers to look beyond existing images of antagonism that have shaped their interpretation of another state’s intentions. This includes looking past their benign self-images and acknowledging the possibility that other states may misperceive their military postures to be offensive. Furthermore, this goes beyond the defensive realist conception of mitigation of security dilemma dynamics. As argued earlier in this chapter, mitigation of security dilemma dynamics from a defensive realist perspective takes place between rational egoists. Such security cooperation is based on self-interest. In contrast, the constructivist perspective contends that policymakers can, through dialogue, reassure one another of their peaceful intentions and thus develop new interpretations of one another. Given that identities and interests are mutually constitutive, states’ interests increasingly reflect their emerging intersubjective identity based on peace and friendship.137 Conclusion This chapter has outlined three distinct theoretical approaches to mitigating security dilemma dynamics. Offensive realist theory contends that due to the irreducible nature of uncertainty in international politics, states cannot move beyond the fatalist logic of insecurity. Even if states recognise that their security postures may be seen as threatening by others, the very nature of uncertainty causes them to act on worst-case assumptions. Although security cooperation between states is possible, this can occur only on a temporary basis.138 Policymakers on either side may enter into cooperative arrangements as tactical manoeuvres designed to enhance their own long-term capacity to renew security competition at a later date. 139 Although crises may be 135 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.158-61. Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, pp.82-83, 132, 160, 168. 137 Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, pp.205-08. 138 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.164-65. 139 Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp.164-65. 136 61 CHAPTER TWO resolved if policymakers choose cooperative arrangements to avoid an unacceptably costly war, these would invariably collapse in the near future and lead to renewed security competition. In short, offensive realist theory indicates that security dilemma dynamics cannot be mitigated. The defensive realist perspective suggests that, under certain conditions, it is possible for policymakers to adopt a mitigator logic of insecurity. As conflict remains a possibility in the anarchic international system, states remain rational egoists in their formulation of security policy and thus continue to prioritise their ability to defend themselves. At the same time, however, under certain circumstances, states can recognise that the danger of conflict can be managed by reducing uncertainty amongst one another. Policymakers can establish security regimes based on norms of restraint, enabling them to achieve long-term cooperation to reduce mutual tensions and build trust. Such trust building is possible through the adoption of less threatening defence postures to signal defensive intent, as well as through the undertaking of significant military and political concessions as costly signals. The long-term sustainability of this basis for cooperation, however, has to be qualified. As Booth and Wheeler point out, the mitigator logic of insecurity shares some elements of fatalist thinking. 140 Similarly, Jervis saw the eventual collapse of the Concert of Europe as grounds for pessimism in assessing the long-term possibilities for mitigation of the security dilemma.141 Although policymakers can exercise security dilemma sensibility, this is possible only when optimal material conditions exist and enable both sides to successfully signal their defensive intent. As Montgomery noted, states seeking to signal their defensive intent have to be able to give up offensive military capabilities without sacrificing weapons that are needed for their defence.142 Whether the material conditions that enabled Gorbachev to implement New Thinking to reassure Reagan without sacrificing Soviet security can be replicated in other strategic settings is open to debate. Although the constructivist approach to mitigation also allows for policymakers to adopt security dilemma sensibility to their interaction, it is also 140 Booth and Wheeler, The Security Dilemma, p.15. Jervis, ‘Security Regimes’, p.368. 142 Montgomery, ‘Breaking out of the Security Dilemma’, p.167. 141 62 CHAPTER TWO important to note that it differs from the defensive realist approach in significant ways. The constructivist approach focuses on how dialogue between policymakers may be seen as a transformative process through which they can gradually assign new meanings to the material capabilities driving security dilemma dynamics. Through contemplating new meaning to their interactions, alternatives to paradoxical security competition can be explored. This enables policymakers to reinterpret an existing antagonistic relationship and consider the possibility that their own security policies postures may have inadvertently contributed to the fears of the other side. 143 Policymakers who show security dilemma sensibility can explore the possibilities for transforming their relations and recognising the security concerns of the other side. By repeated acts of cooperative behaviour in reducing tension and addressing the security concerns of others, policymakers give increased meaning to the Lockean logic of anarchy, causing long-term security cooperation to become a part of their identity and interests. Over the long-term, such interaction may lead to internalisation of a Kantian intersubjective identity. In other words, a socially constructed antagonistic relationship can, over time, be reformed to allow for a peaceful, friendly relationship between former adversary states. These three theoretical perspectives indicate three distinct analytical approaches to understanding how states may respond to security dilemma dynamics. In light of the academic debates surrounding each of these theoretical approaches, the thesis proceeds in Chapters Three, Four and Five to investigate how a case study of US-North Korean interaction reflects the contending claims advanced by these theoretical perspectives. Specifically, the case study raises the following questions: is it possible for states to show security dilemma sensibility in their interactions when the security dilemma dynamic is between a large state and a significantly weaker one? Can policymakers in such a situation successfully send costly signals that will build trust? Can small weak states, when faced with a stronger state, be successfully reassured into giving up their nuclear weapon capabilities? To what extent can dialogue transform a hostile relationship into a cooperative one? How serious is the issue of ‘future uncertainty’ in preventing states from transforming their hostile 143 Fierke, Changing Games, Changing Strategies, p.126. 63 CHAPTER TWO images of one another? These questions, and their implications for mitigation of security dilemma dynamics, will be addressed in the following chapters.144 144 Chapter Three examines the period of US-North Korean interaction from 1950 to 1992 to provide a background for Chapters Four and Five. 64