DIAGNOSIS OF MYCOPLASMA CONJUNCTIVAE AND

advertisement

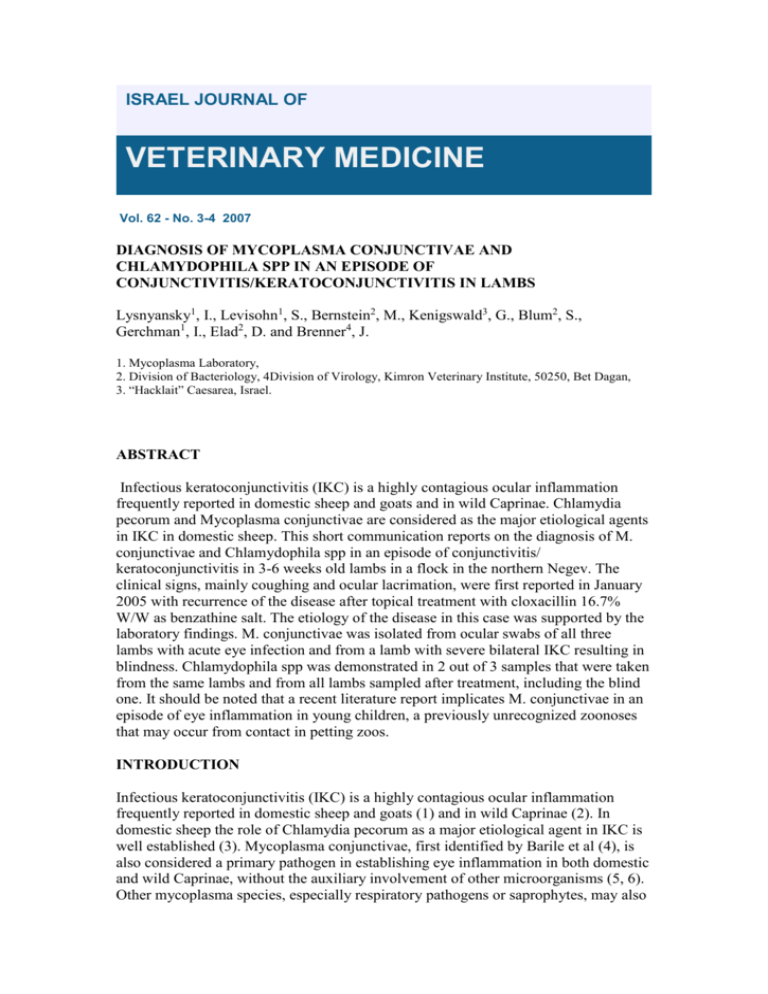

ISRAEL JOURNAL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE Vol. 62 - No. 3-4 2007 DIAGNOSIS OF MYCOPLASMA CONJUNCTIVAE AND CHLAMYDOPHILA SPP IN AN EPISODE OF CONJUNCTIVITIS/KERATOCONJUNCTIVITIS IN LAMBS Lysnyansky1, I., Levisohn1, S., Bernstein2, M., Kenigswald3, G., Blum2, S., Gerchman1, I., Elad2, D. and Brenner4, J. 1. Mycoplasma Laboratory, 2. Division of Bacteriology, 4Division of Virology, Kimron Veterinary Institute, 50250, Bet Dagan, 3. “Hacklait” Caesarea, Israel. ABSTRACT Infectious keratoconjunctivitis (IKC) is a highly contagious ocular inflammation frequently reported in domestic sheep and goats and in wild Caprinae. Chlamydia pecorum and Mycoplasma conjunctivae are considered as the major etiological agents in IKC in domestic sheep. This short communication reports on the diagnosis of M. conjunctivae and Chlamydophila spp in an episode of conjunctivitis/ keratoconjunctivitis in 3-6 weeks old lambs in a flock in the northern Negev. The clinical signs, mainly coughing and ocular lacrimation, were first reported in January 2005 with recurrence of the disease after topical treatment with cloxacillin 16.7% W/W as benzathine salt. The etiology of the disease in this case was supported by the laboratory findings. M. conjunctivae was isolated from ocular swabs of all three lambs with acute eye infection and from a lamb with severe bilateral IKC resulting in blindness. Chlamydophila spp was demonstrated in 2 out of 3 samples that were taken from the same lambs and from all lambs sampled after treatment, including the blind one. It should be noted that a recent literature report implicates M. conjunctivae in an episode of eye inflammation in young children, a previously unrecognized zoonoses that may occur from contact in petting zoos. INTRODUCTION Infectious keratoconjunctivitis (IKC) is a highly contagious ocular inflammation frequently reported in domestic sheep and goats (1) and in wild Caprinae (2). In domestic sheep the role of Chlamydia pecorum as a major etiological agent in IKC is well established (3). Mycoplasma conjunctivae, first identified by Barile et al (4), is also considered a primary pathogen in establishing eye inflammation in both domestic and wild Caprinae, without the auxiliary involvement of other microorganisms (5, 6). Other mycoplasma species, especially respiratory pathogens or saprophytes, may also be isolated from the corneal sac of diseased or clinically healthy animals (7,8). Mechanic or environmental/climatic factors may act synergistically together with the infectious agent to establish an inflammation, namely conjunctivitis, that may be transient or progress to keratoconjunctivitis. At this stage, when the cornea is involved, the disease may further progress toward corneal ulceration with temporary or permanent blindness. The importance of M. conjunctivae in the etiology of IKC is supported by experimental infection studies (9, 10). However, under field conditions, other microorganisms, usually Branhamella ovis or Moraxella ovis, are frequently isolated concomitantly in addition to the possible presence of Chlamydophila spp. In recent years, interest in M. conjunctivae infection has increased markedly due to the impact of the disease on free-ranging ibex (Capra i. ibex) and chamois (Rupicapra r. rupicapra) populations in the Alps and other mountain ranges in Europe (2, 11). Diagnosis or identification of M. conjunctivae isolates may be carried out by the use of a species-specific 16S-rRNA PCR test (6, 12, 13). Use of a gene-targeted-PCR test detecting the lppS gene has clearly established transmission of M. conjunctivae from asymptomatic domestic sheep to wild caprinae sharing grazing land (11). The wild caprinae usually develop clinical IKC with resultant blindness, resulting in death under natural conditions. While of great value in monitoring the presence of M. conjunctivae, especially in free-ranging animals that are difficult to sample, targeted molecular diagnosis may not detect all the etiological agents in a multifactorial disease. This short communication reports on the diagnosis of M. conjunctivae and Chlamydophila spp in an episode of conjunctivitis/keratoconjunctivitis in lambs three to six weeks of age. CASE HISTORY Clinical signs began in January 2005, in a sheep flock consisting of 500 ewes with 1.8 prolificacy (=900 lambs/year). During the cold season, from January through March, cough, eye inflammation and lacrimation was noted in 3-6 weeks old lambs (30 lambs out of approximately 300 born during this period). Three ocular swabs without transport media were submitted for diagnosis (Sampling time I). The affected lambs were treated with cloxacillin 16.7% W/W (as benzathine salt, Northborough, Ireland) ointment inserted into the lower conjunctival sac for 10 days, until the clinical signs receded. The treatment resulted in recession of the clinical signs. Approximately two weeks after cessation of treatment clinical signs reappeared in some of the treated animals. Six lambs, in a pen of 20, showed active conjunctivitis (Picture A) that progressed into permanent blindness (Pictures B). Nasal and ocular samples were taken in transport medium for diagnosis from three diseased lambs with conjunctivitis and from two asymptomatic convalescent animals (Sample time II). MATERIALS AND METHODS Microbiological methods Routine bacteriological assays for the isolation of the ocular and nasal flora are described elsewhere (14, 15, 16). For isolation of mycoplasmas, ocular swabs submitted for routine diagnosis (Sample time I) were inoculated into standard Hayflick-type mycoplasma broth (17). At sampling time II, nasal and ocular swabs were inoculated into FF (modified Friis) medium mycoplasma broth with the addition of 67 μg/ml cefoperazone (cefobid) and 200 μg/ml bacitracin (Sigma) (17). The cultures were propagated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% carbon dioxide. Identification of mycoplasma isolates was by indirect immunofluorescence of mycoplasma colonies with species-specific polyclonal antibodies from the Mycoplasma Reference Laboratory, Aarhus, Denmark, using standard methods (18). Chlamydophila identification Conjunctival swabs were rolled onto microscope slides, air-dried, fixed with cold acetone for 10 min and frozen at –200C till examined. These samples were tested for Chlamydophila spp by direct immunofluorescence with a monoclonal chlamydial group-specific fluorescein conjugate (Cellabs, Australia) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Samples were considered positive if 10 or more fluorescing elements with characteristic morphology were seen per high power field. RESULTS Bacterial findings for ocular swabs are summarized in Table 1. Table 1: Identification of putative pathogens in ocular swab samples M. Clinical status Chlamydophila spp* conjunctivae * 2/3 3/3 Acute infection 3/3 1/3 Symptomatic 2/2 0/2 Asymptomatic Sampling time I Sampling time II (post-treatment) *positive/teste d Chlamydophila spp was demonstrated in two out of two ocular samples taken from convalescent lambs and five out of six ocular swabs from lambs with acute or recurrent conjunctivitis (Table I). The number of fluorescent-stained elementary bodies differed markedly among the samples. M. conjunctivae was isolated from all three ocular swabs taken during the acute stage of the disease (Sampling time I). At sampling time II, two animals presented with conjunctivitis and a third animal showed bilateral keratoconjunctivitis resulting in blindness. M. conjunctivae was isolated from only one sample after treatment (the blind animal), irrespective of the presence of clinical signs. Each of the three ocular samples from the acute stage of disease showed a different bacterial flora. One sample yielded mixed bacteria flora with the saprophytic Mycoplasma arginini whereas the others yielded Moraxella ovis or Staphylococcus plasma coagulase negative or Streptococcus α-hemolytic with no additional mycoplasma. Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae was isolated from four out of the five nasal swabs tested. No viral assays were attempted. Figure Legend A - Acute conjunctivitis in a 6 weeks old lamb. The disease was responsive to topical treatment with antibiotics ,with disappearance of clinical signs. In some animals the lesion reappeared after the cessation of antibiotics treatment. B - Progression of disease to keratoconjunctivitis (bilateral blindness), and (B1) where the necrotic center with ulceration is evident. DISCUSSION This study clearly demonstrates the presence of two major pathogens, M. conjunctivae and Chlamydophila spp, in an outbreak of IKC in young lambs. This is the first identification of M. conjunctivae in sheep in Israel. Topical treatment led to improvement of the clinical signs, but there was resurgence of the disease after treatment was finished. Notably, isolation of M. conjunctivae was successful in only one of the five samples from animals that had been treated. This underscores the problems in determining the etiology of a disease in animals after antibiotic treatment . M .ovipneumoniae is recognized as a major pathogenic agent of the sheep respiratory tract, together with or in the absence of Pasteurella spp. (19, 20). The organism is somewhat fastidious and may be difficult to isolate, especially in mixed infection with nonmycoplasmal bacteria. Diagnosis of M. ovipneumoniae infection in this case is the first report in Israel during recent years ,but the prevalence of the organism is not known since it is not detected by mycoplasma culture methods routinely used for diagnosis. Although M. ovipneumoniae was isolated from four out of five lambs, it is not known to what degree the flock suffered from respiratory disease. It is not clear if there is a direct association between respiratory infection and conjunctivitis and respiratory pathogens may be isolated from the ocular sac in the absence of disease (7, 8). In a previous study of bovine pink-eye, we reported on the presence in ocular secretions of Mycoplasma bovioculi in mixed infection with Mycoplasma bovis, a major respiratory pathogen (16), suggesting potentiation or exacerbation of the ocular disease by the respiratory disease. In recent years there has been increasing recognition of the prevalence and importance of disease syndromes of multifactorial etiology. It is often difficult to elucidate the role of each of the infecting microorganisms, especially because the relative importance of each may vary in different cases. Synergism between Mycoplasma ssp and other bacteria or viruses in ruminants has been frequently described .)20 ,19( However, the organisms may act sequentially rather than in concert and may not be present in the lesion or the affected organ at the same time . The episode of IKC described in this report is not a novel occurrence in this flock. Although clinical signs have been reported in previous lambing seasons, no nasal or ocular swabs were sent to the Kimron Veterinary Institute for bacterial diagnosis, and it is suggested that the pathogens are endemic in the flock. However, this is the first time that it has been possible to elucidate the etiology of the disease. Asymptomatic animals serve as a reservoir of infection for the new-born lambs. The sheep may also serve as a source of infection for freeranging wild Caprinae that share the pasture, as has been reported in Europe (2, 11). Future use of molecular diagnostic tests may simplify sampling and laboratory testing, enabling more rapid diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Since sheep conjunctivitis is not an emerging disease in Israel and was described in 1951 by Komarov (21), we would suggest our practitioners be aware of the possibility that M. conjunctivae is also considered zoonotic since this pathogen has been implicated in an episode of eye inflammation in young children (22). Lambs, kids and small wild ruminants are very popular in the petting zoos in Israel. Therefore, we should be alert to any clinical signs indicative of conjunctivitis in these animals as they might potentially be hazardous for young children. REFERENCES .1Jones, G. E. Infectious Keratoconjunctivitis, 2nd edition .Blackwell, Oxford. 1991. .2Giacometti, M., Janovsky, M., Belloy, L ,.and Frey, J. Infectious keratoconjunctivitis of ibex, chamois and other Caprinae. Rev Sci Tech. 21:335-345. 2002. .3Hosie, B. D .Ocular diseases. In "Diseases of Sheep" (Aiken, I.D.), 4th Edition, Blackwell, Oxford UK. pp. 341-345. 2007. .4Barile, M .F., Del Giudice, R. A., & Tully, J. G. Isolation and characterization of Mycoplasma conjunctivae sp. n. from sheep and goats with keratoconjunctivitis. Infect. Immun. 5: 70-76. 1972. .5Egwu, G .O. Outbreak of ovine infectious kerato-conjunctivitis caused by Mycoplasma conjunctivae. Small Ruminant Research 9:189-196. 1992. .6Motha, M. X ,.Frey, J., Hansen, M. F., Jamaludin, R., and Tham, K .M. Detection of Mycoplasma conjunctivae in sheep affected with conjunctivitis and infectious keratoconjunctivitis. New Zealand Vet. J. 51:186-190. 2003. .7Jones, G. E., A. Foggie, A. Sutherland, and D. B .Harker. Mycoplasmas and ovine keratoconjunctivitis. Vet Rec 99:137-41. 1976. .8Gonzalez-Candela, M., G. Verbisck-Bucker, P. Martin-Atance, M .J. Cubero-Pablo, and L. Leon-Vizcaino. Mycoplasmas isolated from Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica hispanica): frequency and risk factors. Vet .Rec. 161:167-8. 2007. .9ter Laak, E.A., Schreuder, B .E. C., Kimman, T.G. and Houwers, D.J. Ovine keratoconjunctivitis experimentally induced by inoculation of Mycoplasma conjunctivae. Vet. Quart.1988 .224-217 :10 . .10Trotter, S. L., Franklin, R. M ,.Baas, E. J., and Barile, M. F. Epidemic caprine keratoconjunctivitis :experimentally induced disease with a pure culture of Mycoplasma conjunctivae .Infect. Immun.18:816-822. 1977. .11Belloy, L., Janovsky, M., Vilei ,E. M., Pilo, P., Giacometti, M. and Frey, F. Molecular epidemiology of Mycoplasma conjunctivae in Caprinae: Transmission across species in natural outbreaks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1913-1919. 2003. .12Giacometti, M ,.Nicolet, J., Johansson, K-E., Naglic, T., Degiorgis, M. P ,.and Frey, J. Detection and identification of Mycoplasma conjunctivae in infectious keratoconjunctivitis by PCR based on the 16S rRNA gene .J. Vet. Med. (B) 46:173-80. 1999. .13Naglic, T., Hajsig ,D., Frey, B., Seol, B., Busch, K. and Lojkic, M .Epidemiology and microbiological study of an outbreak of infectious keratoconjunctivitis in sheep. Vet. Rec.147: 72-75. 2000. .14Elad, D ,.Yeruham, I. and Bernstein, M. Moraxella ovis in cases of infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK) in Israel. J. Vet. Med. B.1988 .434-431 :35 . .15Yeruham, I., Perl, S., Hadani, A ,.Elad, D. and De-Lange, A. Survey of eye pathology in a dairy herd in the Jericho Valley in Israel .Isr. J. Vet. Med. 46: 142-144. 1991. .16Levisohn, S ,.Garazi, S., Gerchman, I. and Brenner, J. Diagnosis of a mixed mycoplasma infection associated with a severe outbreak of bovine pinkeye in young calves. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 16:579-581. 2004. .17Freundt, E. A. Culture media for classic mycoplasmas. In“ Methods in Mycoplasmology ( ” Razin, S and Tully, J. G. Eds ,).Vol.1. Academic Press, New York. , pp. 127-136. 1983. 18. Gardella, R. S., Del Giudice, R. A. and Tully, J. G. Immuno-fluorescence. In“ Methods in Mycoplasmology( ”Razin, S and Tully, J. G. Eds.), Vol.1. Academic Press, New York .pp. 431439. 1983. .19Alley, M.R., Quinlan, J. R .and Clarke, J.K. The prevalence of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae and Mcoplasma arginini in the respiratory tract of sheep. N. Z .Vet. J. 23: 137-141.1975. .20McAuliffe, L., Hatchell, F.M ,.Ayling, R.D., King, A.I. M. and Nicholas, R.A. J. Detection of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae in Pasteurella-vaccinated sheep flocks with respiratory disease in England. Vet. Rec. 153: 688-689.2003 . .21Komarov, A. 1951. Conjunctivitis of sheep in Israel .Refuah Vet. 8: 46. .22Deutz, A., Spergser, J., Frey ,J., Rosengarten, R. and Kofer, J. Mycoplasma conjunctivae in two sheep farms- clinics, diagnostics and epidemiology. Tierarztl. Mschr. 91:152-157. 2004.