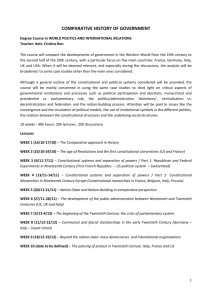

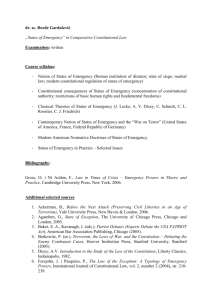

Part Two - The Nature of Constitutional Law

advertisement