[2012] NSWWCCPD 1 - Workers Compensation Commission

advertisement

![[2012] NSWWCCPD 1 - Workers Compensation Commission](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007670694_2-e65a9a8a83455b9777ea984c2ac37a69-768x994.png)

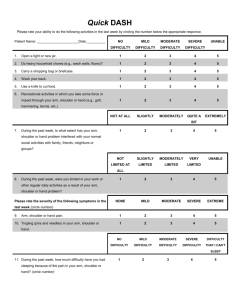

Issue 2: February 2012 On Appeal Welcome to the 2nd issue of ‘On Appeal’ for 2012. Issue 2 – February 2012 includes a summary of the January 2012 decisions. These summaries are prepared by the Presidential Unit and are designed to provide a brief overview of, and introduction to, the most recent Presidential and Court of Appeal decisions. They are not intended to be a substitute for reading the decisions in full, nor are they a substitute for a decision maker’s independent research. Please note that the following abbreviations are used throughout these summaries: ADP AMS Commission DP MAC Reply 1987 Act 1998 Act 2003 Regulation 2010 Regulation 2010 Rules 2011 Rules Acting Deputy President Approved Medical Specialist Workers Compensation Commission Deputy President Medical Assessment Certificate Reply to Application to Resolve a Dispute Workers Compensation Act 1987 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Workers Compensation Regulation 2003 Workers Compensation Regulation 2010 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2010 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2011 Level 21 1 Oxford Street Darlinghurst NSW 2010 PO Box 594 Darlinghurst 1300 Australia Ph 1300 368018 TTY 02 9261 3334 www.wcc.nsw.gov.au 1 Table of Contents Presidential Decisions: Department of Education and Communities v Layton [2012] NSWWCCPD 2 ................. 3 Assessment of ability to earn s 40(2)(b) of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; application of principles in Mitchell v Central West Health Service (1997) 14 NSWCCR 526; leave to appeal out of time s 352(4) of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; fresh evidence on appeal s 352(6) of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 ...... 3 Australian Traineeship System v Turner [2012] NSWWCCPD 4 ...................................... 6 Compensation for consequential loss; relevance of subsequent employment; application of principles in Cluff v Dorahy Bros (Wholesale) Pty Ltd [1972] 2 NSWLR 435; alleged absence of evidence ..................................................................................... 6 Preston v Randwick City Council [2012] NSWWCCPD 1 ................................................ 10 Challenge to orders made by consent; nature of appeal brought pursuant to s 352 of Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; appeal proceedings misconceived; dismissal of appeal proceedings: s 354(7A) Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 .............................................. 10 McGrath v Nestle Australia Ltd [2012] NSWWCCPD 3 ................................................... 12 Incapacity; erroneous finding of partial incapacity; failure by the Arbitrator to take into account evidence relevant to matter in dispute; correction of error on appeal. .......... 12 2 Department of Education and Communities v Layton [2012] NSWWCCPD 2 Assessment of ability to earn s 40(2)(b) of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; application of principles in Mitchell v Central West Health Service (1997) 14 NSWCCR 526; leave to appeal out of time s 352(4) of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; fresh evidence on appeal s 352(6) of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Keating P 18 January 2012 Facts: Ms Layton was employed by the Department of Education and Communities (the appellant) as a school attendance officer. On 4 May 2006, Ms Layton stepped into a depression on a grass footpath in the course of her employment, and was injured. Ms Layton claimed to have suffered injuries to her neck and back. Liability was initially accepted in respect of both injuries and voluntary payments of compensation were made until 1 July 2010. On 4 December 2009, Ms Layton entered into a complying agreement pursuant to s 66A of the 1987 Act, accepting lump sum compensation of $9,187.50 in respect of a seven per cent whole person impairment. On 12 June 2010, Ms Layton was assessed by Associate Professor Oakeshott at Allianz’s request. Following this assessment, Allianz issued a notice under s 74 denying liability for any further compensation on the basis that, at the time of the assessment, there was no objective clinical evidence of any physical injury or underlying pathology to the worker’s back, neck or limbs that could be attributed to the 4 May 2006 injury. On 31 May 2011, Ms Layton lodged an Application to Resolve a Dispute with the Commission. She claimed weekly compensation from 8 December 2010 to date and continuing, and lump sum compensation in respect of 16 per cent whole person impairment (less compensation previously paid in respect of the agreed seven per cent impairment) arising from the alleged injuries to her neck and back. At the hearing before the Arbitrator, the parties agreed that the only matters for determination by the Commission were: (a) whether the worker suffered an injury to her neck as a result of the incident on 4 May 2006, and (b) the quantum of any entitlement to weekly compensation pursuant to s 40. The Arbitrator concluded that Ms Layton had sustained injuries to both her lumbar and cervical spines as a result of the incident on 4 May 2006. The Arbitrator determined that she remained partially incapacitated and awarded her compensation at the maximum payable to a single adult person from 8 December 2010. The Department of Education and Communities appealed and submitted that the Arbitrator erred: (a) by failing to determine the dispute in relation to the worker’s entitlement to workers compensation under s 40 of the 1987 Act in accordance with the 3 decision of the Court of Appeal in Mitchell v Central West Health Service (1997) 14 NSWCCR 526 (Mitchell); (b) by failing to consider all available evidence in relation to the issue of the worker’s capacity for work, and (c) by failing to provide any reasons for his determination of the dispute under s 40. Held: Paragraph one of the Arbitrator’s decision in so far as it related to the assessment of Ms Layton’s entitlements under s 40 was revoked and remitted for redetermination by another Arbitrator. All other findings and orders were confirmed. Time 1. The appeal was lodged out of time (see [13] – [24]). The time to appeal was extended, having regard to Pt 16 r 16.2(12) of the 2011 Rules and Gallo v Dawson [1990] HCA 30; 93 ALR 479 at 408 (Gallo) [25] – [29]. Fresh evidence 2. The appellant’s application to rely on a MAC as fresh evidence was refused. It was determined that the matter was to be re-determined. There was no injustice in not admitting the document as each party would be free to tender, subject to the Commission’s Rules and the Workers Compensation Regulation 2010, such further evidence as necessary [33] – [39]. Section 40 3. The appellant submitted that the Arbitrator erred by failing to assess the compensation payable under s 40 in accordance with the decision in Mitchell v Central West Health Service (1997) 14 NSWCCR 526 (Mitchell). 4. The Arbitrator dealt with the question of Ms Layton’s entitlement to weekly compensation as follows: “I have no difficulty in accepting that the applicant suffers ongoing partial incapacity as a result of injuries occurring on 4 May 2006. The parties have agreed that the comparable earnings at the present time are $1,556.93 per week and taking into account all available medical as well as the lay evidence I have no hesitation in accepting the applicant’s counsel’s submissions to the effect that the section 40 entitlement would equate in monetary terms to the weekly rate of a single adult person who is totally incapacitated. Importantly, I have determined that the applicant’s maximum earning capacity would not exceed $1,000 per week.” (emphasis added). 5. The Court of Appeal in Mitchell set out five steps that must be taken in making an award under s 40 of the 1987 Act. In Mitchell, the following was said in relation to s 40(2)(b) (at 532): “The appellant correctly points out that section 40(2)(b) speaks of ‘the average weekly amount’. The appellant accepts that, since section 40(2)(b) is dealing with a question of earning capacity, the Court is obviously required to presume that the worker will maximise his or her available opportunities. Nevertheless what is ultimately to be sought is a weekly average. 4 An appellate court should approach these matters with a disposition against finding that an experienced judge of a specialist court would misapply a frequently encountered provision such as section 40. However, the critical finding by the trial Judge was ‘ … that the applicant would not be able to earn more than $700 per week … ’. The requirement of the statute (section 40(2)(b)) was to determine ‘the average weekly amount that the worker … would be able to earn in some suitable employment, from time to time after the injury … ’. The emphases are added. The meaning conveyed by his Honour’s words delineates the establishment of a ceiling rather than, as the statute required, evaluation of a level of ability. The apparent departure from compliance with the prescription of section 40(2)(b) entitles the appellant, in our opinion, to judgment that his challenge has been made good in this regard.” 6. The Arbitrator’s approach to his assessment of the average weekly amount which Ms Layton was earning or would be able to earn in some suitable employment (s 40(2)(b)) was in error. By assessing a ceiling rather than, as the statute requires, an evaluation of the worker’s ability to earn, the Arbitrator made precisely the same error as the trial judge made in Mitchell [51]. 7. As this ground of appeal was made out, it was unnecessary to consider the remaining grounds of appeal. 8. There was not sufficient evidence available to re-determine Ms Layton’s entitlement to weekly compensation. Therefore, the matter was remitted to another Arbitrator for rehearing on the question of the assessment of Ms Layton’s entitlement to weekly compensation under s 40 of the 1987 Act [52] – [58]. 9. The Arbitrator’s determination that Ms Layton remained partially incapacitated was confirmed [59]. 5 Australian Traineeship System v Turner [2012] NSWWCCPD 4 Compensation for consequential loss; relevance of subsequent employment; application of principles in Cluff v Dorahy Bros (Wholesale) Pty Ltd [1972] 2 NSWLR 435; alleged absence of evidence Roche DP 31 January 2012 Facts: Brian Turner started work as a cleaner with the appellant employer. On 8 April 2002, he injured his right shoulder in the course of his employment. Liability was accepted and Mr Turner later settled a claim for lump sum compensation in respect of a six per cent whole person impairment because of the condition of his right shoulder. In September 2004, Mr Turner started work as a doorman at Blacktown Workers Club (the Club) where he worked 35-38 hours per week until sometime in 2005. His statements did not deal with the work he performed at the Club. In 2005, he developed pain and restrictions in his left shoulder because he had been favouring his injured right shoulder. He had surgery on his right shoulder on 8 February 2006, 4 April 2007 and 25 July 2007. On 17 June 2010, Mr Turner claimed lump sum compensation in respect of a 17 per cent whole person impairment because of a deterioration in his right shoulder and because of symptoms and restrictions in his left shoulder as a result of overuse of that shoulder consequent upon the right shoulder injury. The appellant disputed liability. It argued that there had been no further impairment of the right shouder. In respect of the left shoulder, it disputed injury, substantial contributing factor, and notice of injury and notice of claim under ss 254 and 261 of the 1998 Act. The Arbitrator found in favour of Mr Turner. With respect to the right shoulder, she found that the allegation of deterioration, with medical evidence to support further whole person impairment, was sufficient to trigger a referral to an AMS. With respect to the left shoulder, she found that Mr Turner may not have been aware of the severity, or possible cause of the medical condition until 2010 and ss 254 and 261 did not preclude him from obtaining benefits in the event that the left shoulder condition was a consequence of the injury to the right shoulder. The issues in dispute in the appeal were whether the Arbitrator: (a) erred in law in determining that the worker suffered an injury to his left shoulder as a consequence of the injury to his right shoulder on 8 April 2002; (b) denied the appellant procedural fairness by requiring it to file its submissions before the worker’s submissions and failing to address the appellant’s written submissions in her decision, and (c) misdirected herself as to the law in finding that the worker suffered a consequential injury to his left shoulder despite the evidence that he engaged in subsequent employment of a physical nature that coincided with the onset of symptoms in his left 6 shoulder and in the absence of evidence sufficient to discharge the onus of proof in relation to the alleged injury to the left shoulder. Held: Arbitrator’s determination amended 1. The appellant’s submissions involved a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the claim and the legal principles and authorities involved. Mr Turner did not allege that he suffered a s 4 injury to his left shoulder. His case was that he had symptoms in his left shoulder as a result of the accepted injury to his right shoulder (Kooragang Cement Pty Ltd v Bates (1994) 35 NSWLR 452; 10 NSWCCR 796). His claim was for a consequential loss (see Roads & Traffic Authority (NSW) v Malcolm (1996) 13 NSWCCR 272 [27]). 2. To succeed, Mr Turner had to establish that the symptoms and restrictions in his left shoulder resulted from the effects of the 2002 injury to his right shoulder. The test of causation in a claim for lump sum compensation is the same as it is in a claim for weekly compensation, namely, whether the loss “resulted from” the relevant work injury (see Sidiropoulos v Able Placements Pty Ltd [1998] NSWCC 7; 1998 16 NSWCCR 123; Rail Services Australia v Dimovski [2004] NSWCA 267; 2004 1 DDCR 648) [28]. 3. It was not disputed that Mr Turner injured his right shoulder in the course of his employment with the appellant on 8 April 2002. He continued at work for the appellant doing light duties for a short time. While doing those duties for the appellant, he relied “heavily” on his left arm when scrubbing tables, which aggravated his left elbow because he was doing more work with his left arm and favouring his right shoulder. While it was acknowledged that the left elbow symptoms did not form part of this claim, it was clear that, because of his right shoulder injury, the worker was favouring his right shoulder as early as 2002. 4. The appellant’s submission that there was no evidence that corroborated that the left elbow symptoms were causally related to the right shoulder injury failed to acknowledge that corroboration is not a requirement in a civil case (Chanaa v Zarour [2011] NSWCA 199 at [86]). It also ignored the fact that the Commission is entitled to rely upon commonsense in evaluating questions of causation (Adelaide Stevedoring Co Ltd v Forst [1940] HCA 45; 1940 64 CLR 538 at 563–564, 569; Tubemakers of Australia Ltd v Fernandez (1976) 50 ALJR 720 per Mason J at 725). Commonsense suggested that, if Mr Turner was doing more work with his left arm, because he was favouring his right shoulder, as he said in his statement dated 16 December 2003, then the symptoms he developed in his left elbow (and later his left shoulder) had resulted from the injury to the right shoulder. The evidence went much further than merely relying on a commonsense inference [43]. 5. Mr Turner began to notice a gradual onset of pain in his left shoulder in early 2005. As the pain was “relatively mild” compared to the pain in his right shoulder, he did not immediately seek treatment for it. Because the pain continued, Mr Turner saw Dr Watts, who referred him for an ultrasound of the left shoulder, which he had on 20 July 2005. This evidence was corroborated by Dr Watts, who said in his report of 23 September 2010 that his first recorded assessment of the left shoulder pain was on 18 July 2005, when Mr Turner “complained of increasing pain due to reliance on this shoulder due to the incapacity on the right”. The reference to “this shoulder” was clearly a reference to the left shoulder. The reference to the “incapacity on the right” was a reference to the restrictions Mr Turner suffered because of the injury to his right shoulder on 8 April 2002 [44]. 7 6. Dr Watts diagnosed a “primary injury” to the right shoulder of a right supraspinatus tendon strain and a “secondary injury” to the left shoulder of a partial supraspinatus tear with acromioclavicular joint inflammation and degenerative change. On the issue of causation of the left shoulder pathology, Dr Watts said the development of pathology in the left shoulder was as a consequence of over reliance on that arm following the injury to the right shoulder [45] – [46]. 7. While Dr Watts (and the Arbitrator) erred in referring to an ultrasound of the left shoulder having been done on 11 June 2002 (that ultrasound was of the right shoulder only), that error did not undermine the conclusion reached. The compelling evidence was that Mr Turner’s left shoulder symptoms developed as a result of additional use of and strain placed on his left shoulder over time because of the injury to his right shoulder. This conclusion did not depend on there having been a normal ultrasound in 2002 and was not altered by the incorrect reference to the 2002 ultrasound being of the left shoulder [52]. It was not accepted that the worker’s medical evidence was not entitled to weight because the doctors took inaccurate or incomplete histories [53]. 8. In Hancock v East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 11, the Court of Appeal examined the application of Makita to proceedings in the Commission. Beazley JA (Giles and Tobias JJA agreeing) said (at [82]) there could be no doubt that the Commission is required to be satisfied that expert evidence provides a satisfactory basis upon which the Commission can make its findings. However, even in evidencebased jurisdictions, “that does not require strict compliance with each and every feature referred to by Heydon JA in Makita to be set out in each and every report”. What is required for satisfactory compliance with the principles governing expert evidence is for the expert’s report to set out “the facts observed, the assumed facts including those garnered from other sources such as the history provided by the appellant, and information from x-rays and other tests” ([85]) [54]. 9. Though Dr Watts erred in referring to the normal ultrasound of the left shoulder in 2002, that error was of no consequence. The relevant history was that the left shoulder was asymptomatic until 2005 and that the symptoms at that time were of increasing pain due to reliance on the left shoulder because of “incapacity on the right”. The incapacity on the right was due to the compensable injury to the right shoulder that occurred on 8 April 2002 [56]. 10. The alleged inadequate histories recorded by Drs Biggs and Dixon (namely, their failure to refer to the work at the Club) were of no consequence. The critical history was that, because of his right shoulder symptoms, Mr Turner used his left arm (and shoulder) more and developed symptoms in his left shoulder. Drs Watts, Biggs and Dixon all took that history and concluded that Mr Turner’s left shoulder symptoms resulted from his right shoulder injury. That history provided a fair climate for the acceptance of their opinions (Paric v John Holland Constructions Pty Ltd [1985] HCA 58; 59 ALJR 844; [1984] 2 NSWLR 505 at 509–510) and the Arbitrator did not err in accepting them [58]. 11. The submission that there was no evidence that the degenerative tear in the supraspinatus tendon revealed in the 2005 ultrasound was causally related to the 2002 right shoulder injury was simply wrong. Dr Watts provided clear evidence to that effect when he said that the development of pathology in the left shoulder was a consequence of over-reliance on that arm following the injury to the right shoulder. His opinion was consistent with the evidence of Drs Biggs and Dixon and was not contradicted by any expert evidence called on behalf of the appellant. The Arbitrator did not err in accepting that evidence [59]. 8 12. The Arbitrator’s reference to Mr Turner’s undated statement being brief and inadequate was a reference to the poor standard of preparation of that statement by his solicitor. While the Deputy President agreed that the statement was less than ideal, that did not mean that Mr Turner’s claim had to fail or that the Arbitrator erred in referring to it. His statement had to be read with the other evidence in the case from the medical experts. That evidence was all one way and comfortably established that Mr Turner did use his left arm more because of his 2002 right shoulder injury and, as a result, developed significant symptoms in his left shoulder. Evidence recorded in a medical history is evidence of the fact (Guthrie v Spence [2009] NSWCA 369 at [75]) [60]. 13. Mr Turner did not have to prove that his left shoulder symptoms were causally related to the work he performed at the Club. His case was that his left shoulder condition resulted from the injury to his right shoulder. The lay and medical evidence provided compelling support for that case. The fact that he was working for the Club at the time he first noticed symptoms in his left shoulder does not detract from the evidence that, as a result of his right shoulder injury, he had to use his left shoulder more and suffered symptoms in his left shoulder [62]. 14. The submission that the worker bore the responsibility for failing to tender evidence regarding his employment at the Club misunderstood the basic legal principles involved. Even if it were found that the left shoulder symptoms had been caused by Mr Turner’s work at the Club, the principles in Cluff v Dorahy Bros (Wholesale) Pty Ltd [1972] 2 NSWLR 435 applied. Mr Turner’s 2002 injury rendered him vulnerable to increased disability by the effects of further work. If his work at the Club brought about those effects, which, on the evidence, was far from clear, it was open to a tribunal of fact to hold that the ultimate incapacity (or impairment) had resulted from the original injury [63]-65]. 15. The Arbitrator erred in her reference to an “injury [to the left shoulder] with a deemed date”. As the disease provisions did not apply, there was no “deemed date” of injury. The relevant injury occurred on 8 April 2002 when Mr Turner injured his right shoulder [71]. 9 Preston v Randwick City Council [2012] NSWWCCPD 1 Challenge to orders made by consent; nature of appeal brought pursuant to s 352 of Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; appeal proceedings misconceived; dismissal of appeal proceedings: s 354(7A) Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 O’Grady DP 10 January 2012 Facts: Mr Stephen Preston commenced proceedings against his employer, Randwick City Council, seeking orders as to his entitlement to workers compensation benefits following an alleged injury in the course of his employment on 6 May 2009. On 17 August 2011, whilst the matter was before Arbitrator Robinson for conciliation and arbitration, the parties’ representatives reached agreement concerning the claim. A document titled “Heads of Agreement” was prepared and signed by the parties’ representatives and Mr Preston. The content of that document formed the basis of the consent orders subsequently made by the Arbitrator which issued on 22 August 2011. Mr Preston was self-represented on appeal. On appeal he alleged that he had signed the “Heads of Agreement’ under duress and that he did not understand the terms of the agreement he had agreed to at the time of signing. He additionally made allegations of misconduct by both opposing counsel and Arbitrator Robinson. On appeal, Mr Preston sought to have the consent orders set aside and the matter “heard afresh”. Orders were also sought in respect of entitlement to weekly payments, medical expenses and lump sums as well as orders concerning the destruction of documents and records. In the alternative, Mr Preston sought a reconsideration of the Arbitrator’s orders. Held: Appeal misconceived pursuant to s 354(7A) of the 1998 Act and dismissed. 2. In exceptional circumstances, the Commission may set aside an order made by consent (Sorcevski v Steggles Pty Ltd (1991) 7 NSWCCR 315). However, Mr Preston’s submissions relied on unsubstantiated allegations and did not justify the setting aside of consent orders [52]. 3. Mr Preston advanced no meaningful argument establishing that the Arbitrator made a relevant error of fact, error of law or error as to the exercise of discretion, concerning the dispute between the parties [45] – [49]. 4. Mr Preston’s request, in the alternative, that his application be “transferred” for reconsideration (per s 350(3) of the 1998 Act) was refused. Mr Preston failed to identify any legislative power available to the Commission allowing the transfer or conversion of an appeal application into a request for reconsideration. The power to remit (s 352(7)) does not extend to circumstances where a litigant, because of failure of the appeal process, seeks reconsideration of the Arbitrator’s decision. 5. It was noted by O’Grady DP that an application for reconsideration requires compliance with the Registrar’s Guidelines dated February 2011 [53] and would be 10 conducted by the Arbitrator who made the orders or, depending on circumstances, another Arbitrator [51]. 6. The appeal was misconceived in terms of s 354(7A) of the 1998 Act and was dismissed [55]. 11 McGrath v Nestle Australia Ltd [2012] NSWWCCPD 3 Incapacity; erroneous finding of partial incapacity; failure by the Arbitrator to take into account evidence relevant to matter in dispute; correction of error on appeal. O’Grady DP 18 January 2012 Facts: Mrs Maria Louise McGrath, the appellant, was employed by Nestle Australia Ltd, the respondent, as an area manager from 5 March 1990 until 4 August 2010 when she resigned on medical advice. Mrs McGrath made a claim for workers’ compensation benefits which the respondent declined. Mrs McGrath filed an application to resolve a dispute alleging psychological injury caused by bullying and harassment by her direct manager during the period January 2010 through to August 2010. The claim made was for weekly compensation on the basis of total incapacity from 4 August 2010. In the alternative, if incapacity was found to be partial, she claimed for the maximum statutory rate payable to a worker with a dependant spouse. The respondent’s defence of the claim had three bases. Firstly, it denied injury. Secondly, if injury was proven, that such injury had arisen from reasonable action taken or proposed to be taken by the employer in relation to performance appraisal or discipline (s 11A). Thirdly, if injury was proven, and s 11A unsatisfied, that Mrs McGrath’s total incapacity had ceased on a date prior to the hearing and that any ongoing incapacity as found was partial. The matter proceeded to Arbitration on 11 August 2011. The Arbitrator found that Ms McGrath had suffered a psychiatric injury in the course of her employment, that the injury was sustained due to the bullying, harassment, inappropriate behaviour and progressive intimidation inflicted upon her by her direct supervisor between January 2010 and August 2010, and that the respondent had failed to establish a defence pursuant to s 11A of the 1987 Act. In respect of incapacity, the Arbitrator determined that Mrs McGrath had been totally incapacitated between 4 August 2010 and 22 January 2011; partially incapacitated from 23 January 2011 and her weekly entitlement to compensation was $310 per week from 23 January 2011 and continuing. Mrs McGrath appealed, arguing that the Arbitrator had erred in finding that she was partially incapacitated from 23 January 2011; failing to find that she was totally incapacitated as a result of the injury and in the manner of the quantifying her weekly entitlements. The Arbitrator noted that Dr Canaris did not specifically comment on Mrs McGrath’s capacity for work. However he drew an inference from the report of 22 January 2011 that it was “clear that by the time of his report [Dr Canaris] thought the applicant was no longer totally incapacitated”. [35] Held: part confirmed, part revoked and re-determined 1. In determining the question of incapacity the Arbitrator over looked or gave too little weight to the following probative evidentiary material [62]: 12 (a) The medical certificates of Dr Lee, Mrs McGrath’s general practitioner. Dr Lee had the management of Mrs McGrath’s medical problems since before she ceased employment with the respondent, and his clinical notes detailed his opinion and prognosis of her condition as diagnosed by him [54]. Dr Lee continued to certify Mrs McGrath as unfit for work post 22 January 2011(the last medical certificate in evidence was dated 5 August 2011) [58]. The Arbitrator accepted Dr Lee’s evidence in respect of his finding on injury and acknowledged that the evidence of Dr Lee was “consistent with [Mrs McGrath] being totally incapacitated for a substantial period” [55]. Yet when drawing the inference as to partial incapacity from the report of Dr Canaris, he had given too little weight to the evidence of Dr Lee. (b) Ms Guzel, psychologist, reported in May 2011 that Mrs McGrath continued to experience symptoms reported in February 2011 which had led to her diagnosis of “Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode” and that Mrs McGrath’s condition had been exacerbated by “ongoing uncertainty” [60]. Ms Guzel also expressed the view, that Dr Lee’s certification that Mrs McGrath was unfit for work, was appropriate [65]. This evidence was overlooked by the Arbitrator. (c) The Arbitrator overlooked the statement of Mrs McGrath made in April 2011, in which she stated that she “cannot envisage ever working again” [59]. 2. It was found on appeal that the Arbitrator had erred in overlooking or giving too little weight to the evidence noted at [1] above. It was found that the weight of evidence supported a conclusion of total incapacity to date [67] and that the Arbitrator had further erred by drawing an inference from the evidence of Dr Canaris that Mrs McGrath was no longer totally incapacitated [63]. 3. O’Grady DP’s finding of total incapacity made it unnecessary to consider the Arbitrator’s quantification of Mrs McGrath’s entitlement to weekly compensation [68]. 4. The Arbitrator’s finding as to incapacity (order 2) was revoked and redetermined. All other orders (1,3-5) were confirmed. 13