“A Community Partnered-Participatory Research Approach to

<run head>Reducing Cancer Disparities in South LA

<run author>Vargas et al.

<T>A Community Partnered-Participatory Research Approach to Reduce Cancer Disparities in

South Los Angeles

<author>Roberto Vargas, MD, MPH

1,2

, Annette E. Maxwell, DrPH

2

, Aziza Lucas-Wright, MA

3

,

Moshen Bazargan, Phd

4

, Carolyn Barlett, RN, MPH

5

, Felicia Jones, RN, BSN

3

, Anthony

Brown 3 , Nell Forge, Phd 4 , James Smith, MD 4 , Jay Vaddama, PhD 4 , and Loretta Jones, PhD 3

<info>(1) David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research; (2) UCLA School of Public Health; (3) Healthy African-

American Families; (4) Charles Drew University, Department of Family Medicine; (5) Los

Angeles County Department of Health Services

<abstract subhead>Abstract

<abstract> Background: Community–academic partnerships may offer opportunities to improve population health in communities that suffer from cancer-related health disparities.

Objectives: This project describes a community partnered effort to promote cancer research and reduce local cancer-related disparities.

Methods: We used a community-partnered participatory research (CPPR) model and modified

Delphi method approach to bring together community and academic stakeholders from South

Los Angeles around reducing cancer disparities.

Results: The 36 member Community–Academic Council consisted of cancer survivors, academics, and representatives of local community-based organizations and churches. Forty-nine unique cancer-related community priorities were collaboratively used to develop shared products. Early CPPR products included convening of a community conference, a

1

collaboratively developed survey instrument, and new partnerships resulting in externally funded projects.

Conclusions: Our approach demonstrates the feasibility of the use of a replicable model of community and academic engagement that has resulted in products developed through collaborative efforts.

<abstract subhead>Keywords

<abstract>Community-based participatory research, health disparities, health promotion, urban health services

<info>Submitted 21 December 2012, revised 25 July 2013, 15 August 2013

<N>In the United States, recent advances in cancer prevention and care have resulted in a decline in cancer mortality.

1

However, the persistence of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in cancer-related outcomes highlight the need to implement interventions aimed at addressing these problems.

2,3

As our understanding of the drivers of these disparities has evolved, the goal of translating this knowledge into improved population health can be advanced by the inclusion of broader perspectives through community–academic partnerships.

We describe an effort to address cancer disparities in a local community in conjunction with an academic medical center’s translational research program. The South Los Angeles (LA) community suffers from some of the worst cancer-related outcomes in LA County, with a cancer death rate of 209 per 100,000 people compared to 165 for the county as a whole and where 32% of adults ages 18 to 64 are uninsured and 28% live in poverty.

4

This region has, however developed a network of community–academic partnerships aimed at addressing health disparities.

5,6

Herein we describe the processes and products from our use of community partnered-participatory research (CPPR) to promote cancer research and reduce cancer-related disparities.

2

<A>Methods

<B>The CPPR Process

<N>CPPR employs the same general principles as community-based participatory research, which strives for equity in all phases of the research process.

7

We chose CPPR because it provides a replicable, four-step framework: 1) Identifying a health issue that fits community priorities and academic capacity to respond; 2) developing a coalition of community, policy, and academic stakeholders that will inform, support, share, and use the resultant products; 3) engaging the community through conferences and workshops that provide information, determine readiness to proceed, and obtain input; and 4) initiating work groups that develop, implement, and evaluate action plans under a leadership council.

8

In addition it was developed locally by faculty and leadership from Charles Drew University and Healthy African-American

Families, 8,9 two institutions that also served leadership roles in this effort. Moreover, the emphasis of “partnered” over “based” highlights the “relationship” over the “place” and that community members are welcomed into the academic environment.

Building on a prior history of collaboration,

6

the partners submitted a proposal framed around using CPPR methods to address cancer disparities in South LA, which has some of the worst cancer outcomes in Los Angeles County.

10 These disparities exist in the context of strong evidence of the efficacy of prevention, detection, and treatment interventions for many cancers.

11

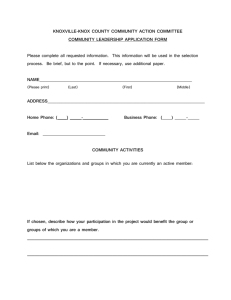

Hence, the first step—identifying a health issue that fits community priorities and academic capacity to respond—was satisfied at the initiation of the project. The approach for step two consisted of inviting existing networks of community-academic partners (which was facilitated by Healthy African-American Families’ prior experience in CPPR), 6 cancer survivors, support organizations, and safety-net providers serving the South LA community to join our stakeholder

3

group, the Community Academic Council (CAC). Community members not attending as part of compensated work activities were provided $50 stipends for participating in each 2-hour inperson meeting, for approximately six bimonthly meetings over the course of a year. Each activity/meeting had a community and academic co-leader that shared responsibilities. The third phase consisted of our convening of a free, full-day, cancer prevention and control conference with real-time translation into Spanish. The fourth phase of this process—initiating work groups that develop, implement, and evaluate action plans—began concurrently with the conference planning activities. Herein we report processes and products resulting from the workgroup’s first year activities and our use of a Delphi method to develop consensus on priorities and actions. We received Institutional Review Board approval from Charles Drew University for the evaluation and description of the CAC activities and meetings.

<B>Selection of Priorities and Content Areas: The Delphi Method

<N>As part of the second phase of our CPPR efforts, we employed a Delphi method approach to elicit priorities from the membership. These priorities became the basis for the workgroup activities and community conference objectives for the CAC. A Delphi process involves identifying and reviewing a set of options, eliciting rankings, discussing differences, modifying materials, and prioritizing them with a statistical marker such as a median/mean to represent the consensus.

12-14

Using a slightly modified process, we presented rankings without requiring respondents to narrow subsequent choices to higher ranked options. We chose this modified method because several members of the team had prior experience with this approach.

15

After reviewing the specific aims of the research project and sharing the public health data describing cancer disparities in the South LA community, we asked each member, “What is the key priority or issue that you feel should be a major focus of the group’s activities to reduce

4

the burden of cancer in this community?” These responses were documented and at a subsequent meeting presented to the group for discussion and categorization into content specific subgroups.

CAC members then anonymously ranked responses, on a 10-point scale, ranging from 1 (most important) to 10 (least important): a) The subgroup categories, b) specific topics within the subgroup, and c) the topics for the conference breakout sessions. This resulted in a prioritized set of content areas for collaborative action and conference topics.

<A>Preliminary Results and Products

<B>Step 1

<N>The product of the first step in our CPPR process was our partnered response to the request for proposals, which resulted in the funding support for this effort.

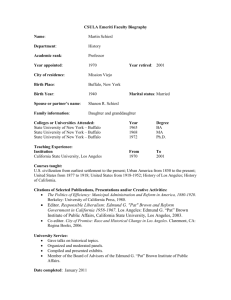

<B>Step 2 Product: Developing a Coalition of Community, Policy, and Academic Stakeholders

That Informs, Supports, Shares, and Uses the Products

<N>The CAC consisted of 36 members, 28% of whom were cancer survivors (African-

American, 89%; White, 6%; Latino, 6%; female, 87%). Seventeen percent stated they were academic center faculty, staff, or students, 75% were community members, and 9% represented a faith-based organization. The Delphi process resulted in 49 priority themes categorized into 7 subgroups (Tables 1–3). Subgroups included health information, alternative healing, mental health, survivorship support, health services, prevention, and risk reduction (Table 1). One group that the CAC ranked separately as potential breakout session topics and interest groups for the conference was newly diagnosed cancers, survivors, patients in treatment, care givers and family, pediatric cancers, high-risk populations, financial struggles, male-specific cancer issues, femalespecific cancer issues, and uncommon cancers (Table 3). The within-subcategory rankings were obtained and used to help the CAC to prioritize efforts for the coming year.

5

<T>Tables 1-3

<B>Step 3 Product: Engaging the Community through Conferences and Workshops

<N>In addition to the monthly CAC calls and meetings, within the first 10 months of convening the group hosted a free community conference, “Prevention, Treatment and Control of Cancer in

Our Community,” which had more than 335 participants. The conference agenda was collaboratively developed in open meetings by systematically reviewing the ranked items from the Delphi process subgroups (Table 2) to determine appropriateness of the theme for the conference agenda. For example, the top ranked choice within the complementary and alternative healing subgroup was spiritual aspects of healing. In discussion, the group then suggested that a

CAC member who was a minister and cancer survivor could serve as one of the plenary speakers and requested that she speak to this topic in the content of her presentation. Other ranked items were used to determine the content for other speakers and panelists or were used in developing an “audience response system” that facilitated learning activities during the conference.

16

<B>Step 4 Products: Initiating Work Groups That Develop, Implement, and Evaluate Action

Plans

<N>The process of action plan development shaped several aspects of the CAC activities during their meetings. In addition to convening the conference, there were additional products and partnerships that were incubated by this CPPR effort. For example, a survey instrument was collaboratively developed by the CAC and fielded during the community conference. A member of the academic team conducted a lay person tutorial on survey research, then during subsequent meetings partners proposed hypotheses to be tested and questions for the survey incorporating themes from the Delphi results. In two subsequent meetings the group vetted questions, pilot

6

tested administration, and edited the survey. This survey was administered during the community conference and results from one set of analyses have recently been published.

17

Other products of the CAC’s efforts included new partnerships between academics and community members. These relationships have resulted in CPPR products that include a pilot project that conducted 801 surveys of cancer knowledge, beliefs, and screening practices across

11 local African-American churches and a qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators to early detection and treatment of cancer in African-American and Latino cancer survivors from

South Los Angeles. One set of CAC members with an interest in post cancer treatment support for African-American couples and intimate partners formed their own 501(c)3 to address these issues. Other CAC products include didactic cancer screening education during CAC meetings, a cancer-focused community health care resource guide, and the compiling of materials on the role of nutrition and exercise in cancer risk reduction that were distributed at the conference and at other community events. The partnerships developed during this time have also resulted in eight grant applications submitted by CAC partners for cancer disparities related projects based in

South Los Angeles. Three of the extramurally funded grants have received more than $550,000 to support intervention, demonstration, and research pilot projects focused on reduction of cancer disparities in this community.

<A>Conclusions

<N>Our approach demonstrates how a replicable model of community–academic engagement can result in products that, at all phases, were developed collaboratively. This effort has provided us with important lessons that have informed our continued efforts and may be of benefit to others who may employ similar approaches. For example, our use of a modified Delphi process helped to ensure transparency and equity in eliciting themes and developing action plans.

7

Specifically, the anonymous voting to rank options and subsequent open discussion of the results provide assurances that all ideas are valued but that decisions were consensus driven. Another example is how financial support for both community and academic partners enabled us to convene a collaboratively developed conference, develop and field a survey instrument, and obtain funding to support implementation of jointly developed projects.

Others who are considering such partnerships should ensure compensation for both academics and community members and that the academic’s support includes time for meetings and planning activities.

Despite these successes, some of our products are limited in their generalizability, because the ranking of community concerns produced by Delphi methodology largely depends on participants’ interests and concerns. In addition, the makeup of CAC participants was predominantly African-American women, thus underrepresenting both male and Latino perspectives. For example, South Los Angeles is roughly 50% Latino; therefore, priorities identified may not reflect the broader community concerns. However, we did promote the conference with Spanish-language flyers, provided real-time Spanish translation via headsets, and 23% of the conference attendees noted Spanish as their primary language spoken.

Subsequent CPPR efforts have now included projects aimed at cancer screening promotion in

Latino churches, continuing to engage Latino participants from the focus group activities, efforts to engage Latino conference participants, and consideration of support for translation at CAC meetings. Other future efforts include leveraging newly funded efforts and sharing of our best practices with organizations like the local American Cancer Society to promote sustainability beyond the support of the initial grant.

8

We have demonstrated that our efforts are in keeping with the current understanding that any effort to reduce disparities should include community partners both in the design and implementation of studies, as well as in translating evidence into sustained health-promoting practices in the community.

3,18

It is our hope that, through describing our processes and products, others may be able to use this model as a practical example of community-academic–partnered efforts to address public health problems.

<A>References

<ref>1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Trends Progress Report – 2011/2012 Update. Bethesda,

MD: National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. Available from: http://progressreport.cancer.gov

2. Eheman C, Henley SJ, Ballard-Barbash R, Jacobs EJ, Schymura MJ, Noone AM, et al.

Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2008, featuring cancers associated with excess weight and lack of sufficient physical activity. Cancer. 2012 May 1;118(9):2338-66.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2009-2010.

Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2009.

4. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Office of Health, Assessment and

Epidemiology. Key indicators of health by services planning area. Los Angeles: County

Department of Public Health; 2009.

5. Norris KC, Brusuelas R, Jones L, Miranda J, Duru OK, Mangione CM. Partnering with community-based organizations: an academic institution's evolving perspective. Ethn Dis. 2007

Winter;17 Suppl 1:S27-32. Erratum in: Ethn Dis. 2007 Spring;17(2):205.

9

6. Wells KB, Staunton A, Norris KC, Bluthenthal R, Chung B, Gelberg L, et al. Building an academic community partnered network for clinical services research: The Community Health

Improvement Collaborative (CHIC). Ethn Dis. 2006 Winter;16 Suppl 1:S3-17.

7. Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010 Nov;100(11):2094-102.

8. Ferré CD, Jones L, Norris KC, Rowley DL. The Healthy African American Families

(HAAF) project: From community-based participatory research to community-partnered participatory research. Ethn Dis. 2010 Winter;20 Suppl 2:S2-1-8.

9. Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in communityparticipatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007 Jan 24;297(4):407-10.

10. Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, Office of Health, Assessment and

Epidemiology. Key Indicators of Health. Los Angeles: County Department of Health Services;

2009.

11. National Cancer Institute. Cancer trends progress report 2009/2010. Bethesda: National

Cancer Institute; 2012.

12. Helmer O. Analysis of the future: Delphi method. Santa Monica, (CA): RAND

Corporation; 1967.

13. Rescher N. Predicting the Future. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1998.

14. Hancock T. Public health planning in the City of Toronto–Part 1. Conceptual planning.

Can J Public Health. 1986;77(3):180–4.

15. Vargas RB, Jones L, Terry C, Nicholas SB, Kopple J, Forge N, et al. Building Bridges to

Optimum Health World Kidney Day Los Angeles 2007 Collaborative. Community-partnered

10

approaches to enhance chronic kidney disease awareness, prevention, and early intervention.

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008 Apr;15(2):153-61.

16. Patel KK, Koegel P, Booker T, Jones L, Wells K. Innovative approaches to obtaining community feedback in the Witness for Wellness experience. Ethn Dis. 2006 Winter;16 Suppl

1:S35-42.

17. Jones L, Bazargan M, Vadgama JV, Lucas-Wright A, Vargas R, Forge N, et al.

Comparing perceived and test-based knowledge of cancer risk and prevention among Hispanics and African Americans: An example of Community Participatory Research. Ethn Dis

2013;23(2):210-6.

18. Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002 Jun;17(6):477-86.

11

<table number>Table 1. <table number>Content-Specific Subgroups

<table>

Subgroup Average Rank

Health services

Prevention/risk reduction

Health information

Alternative healing

Survivorship

2.27

2.44

3.22

4.07

4.31

Mental health 4.33

<table note>Note: Rankings range from 1 = most important to 10 = least important.

1

2

3

4

5

6

12

<table number>Table 2. <table number>Topics Within Subgroups (underlined) and Within

Group Average Rank Scores

<table>

Topic Average Rank

Health information

Mammography controversies and radiation risks

Dual messages: What message is the community hearing?

Cancer myth versus facts

3.69

4.00

4.00

1

2

2

4.19

4.81

4.93

3

4

5

How is the message being delivered?

Where they are getting their information? Who to trust?

Sharing information across community based organizations and academic partners: What are their activities who they are helping?; What are the current research and data collection efforts in our community

Early prostate cancer detection Black males

Advocacy–navigation

Genetics

Complementary and alternative healing

Spiritual aspects of healing

Alternative medicine/Integrative medicine

5.19

5.88

6.44

1.73

2.07

2.20

6

7

8

1

2

3 Blending of Eastern and Western Medicine

Mental health

Depression

Mind-body-spirit connection

Counseling/support for partners/family

Survivorship

Side effects of surgery and treatment

Support during chemotherapy and treatment

Access to services post-surgery and treatment

Having survivors tell their stories

Health services

How to navigate the system

Type of health insurance, including Medicare/Medicaid

Insurance and cancer

Access to services in our community

1.76

2.00

2.24

2.18

2.35

2.53

2.94

3.00

3.18

3.41

3.65

3.71

4.06

1

2

3

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

5

6

Referrals to services within the community resource guide

Patient advocates

Cancer prevention and risk reduction

Risk specific to African Americans

Food/nutrition

Environmental risk factors

Children’s health: How to begin healthy activities and eating habits earlier

Diet

2.94

3.18

3.19

4.40

4.50

1

2

3

4

5

13

Exercise 4.65

Health policies promoting prevention and risk reduction

Alcohol and cancer risk

5.75

6.53

<table note>Note: Rankings range from 1 = most important to 10 = least important.

6

7

8

14

<table number>Table 3. <table title>Subgroup of Conference Breakout Sessions

<table>

Session

Newly diagnosed

In treatment

At risk/high risk

Financial struggles

Female specific cancer issues

Care givers and family

Male specific cancer issues

Survivors

Pediatric cancer

5.65

7.19

Uncommon cancers 7.82

<table note>Note: Rankings range from 1 = most important to 10 = least important.

Average Rank

3.71 1

4.31

4.69

2

3

4.82

5.19

5.29

5.63

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

15