Chest Exam & Breath Retraining

advertisement

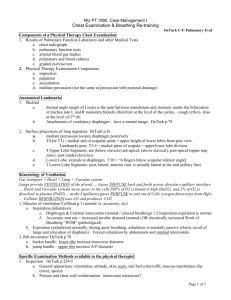

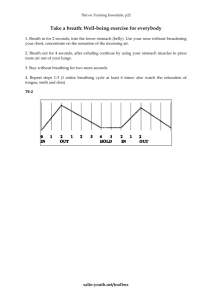

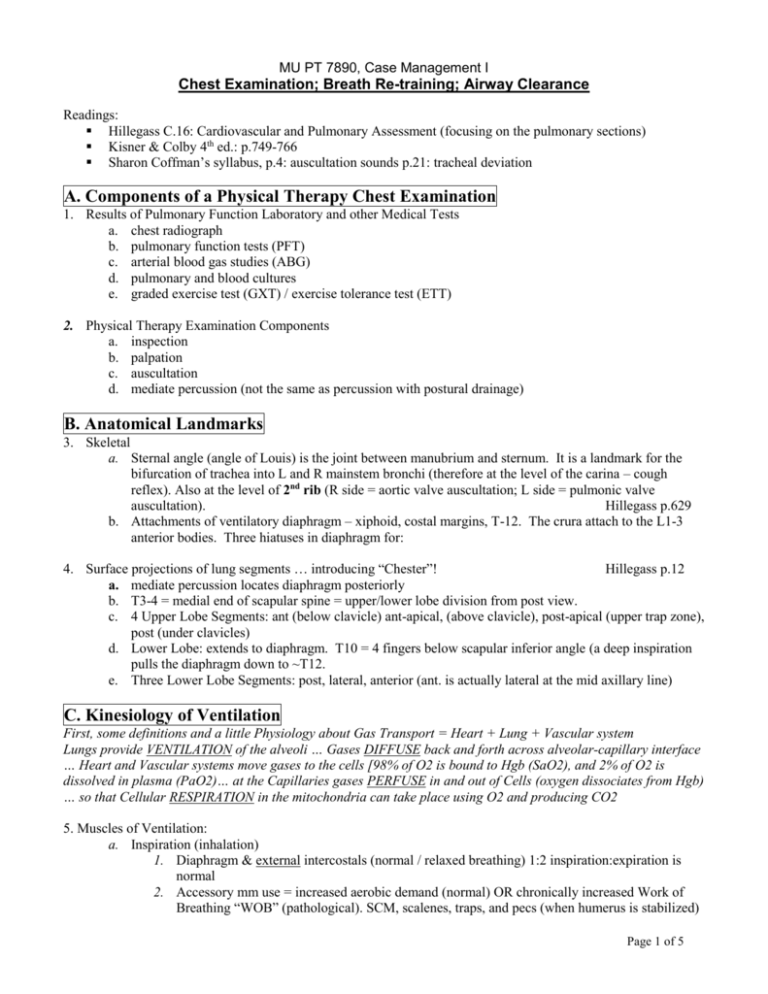

MU PT 7890, Case Management I Chest Examination; Breath Re-training; Airway Clearance Readings: Hillegass C.16: Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Assessment (focusing on the pulmonary sections) Kisner & Colby 4th ed.: p.749-766 Sharon Coffman’s syllabus, p.4: auscultation sounds p.21: tracheal deviation A. Components of a Physical Therapy Chest Examination 1. Results of Pulmonary Function Laboratory and other Medical Tests a. chest radiograph b. pulmonary function tests (PFT) c. arterial blood gas studies (ABG) d. pulmonary and blood cultures e. graded exercise test (GXT) / exercise tolerance test (ETT) 2. Physical Therapy Examination Components a. inspection b. palpation c. auscultation d. mediate percussion (not the same as percussion with postural drainage) B. Anatomical Landmarks 3. Skeletal a. Sternal angle (angle of Louis) is the joint between manubrium and sternum. It is a landmark for the bifurcation of trachea into L and R mainstem bronchi (therefore at the level of the carina – cough reflex). Also at the level of 2nd rib (R side = aortic valve auscultation; L side = pulmonic valve auscultation). Hillegass p.629 b. Attachments of ventilatory diaphragm – xiphoid, costal margins, T-12. The crura attach to the L1-3 anterior bodies. Three hiatuses in diaphragm for: 4. Surface projections of lung segments … introducing “Chester”! Hillegass p.12 a. mediate percussion locates diaphragm posteriorly b. T3-4 = medial end of scapular spine = upper/lower lobe division from post view. c. 4 Upper Lobe Segments: ant (below clavicle) ant-apical, (above clavicle), post-apical (upper trap zone), post (under clavicles) d. Lower Lobe: extends to diaphragm. T10 = 4 fingers below scapular inferior angle (a deep inspiration pulls the diaphragm down to ~T12. e. Three Lower Lobe Segments: post, lateral, anterior (ant. is actually lateral at the mid axillary line) C. Kinesiology of Ventilation First, some definitions and a little Physiology about Gas Transport = Heart + Lung + Vascular system Lungs provide VENTILATION of the alveoli … Gases DIFFUSE back and forth across alveolar-capillary interface … Heart and Vascular systems move gases to the cells [98% of O2 is bound to Hgb (SaO2), and 2% of O2 is dissolved in plasma (PaO2)… at the Capillaries gases PERFUSE in and out of Cells (oxygen dissociates from Hgb) … so that Cellular RESPIRATION in the mitochondria can take place using O2 and producing CO2 5. Muscles of Ventilation: a. Inspiration (inhalation) 1. Diaphragm & external intercostals (normal / relaxed breathing) 1:2 inspiration:expiration is normal 2. Accessory mm use = increased aerobic demand (normal) OR chronically increased Work of Breathing “WOB” (pathological). SCM, scalenes, traps, and pecs (when humerus is stabilized) Page 1 of 5 b. Expiration (exhalation) normally, during quiet breathing, exhalation is passive from the elastic recoil of lungs and relaxation of diaphram. However forced exhalation during labored breathing, or to produce an effective cough is done by action of the abdominals and internal intercostals 6. Rib movement: a. Task: Bucket handle: lower ribs increase transverse diameter (place hands on lateral costal margins). b. Task: Pump handle – upper ribs increase A-P diameter (place hand on mid sternum). D. Specific Examination Methods available to the physical therapist 7. Inspection a. General appearance: orientation, attitude, skin, scars, nail bed color/refill, mucous membranes (lip color), speech b. Posture and chest wall conformation. Intercostal retractions? c. Head and neck: hypertrophy of SCM, Scalenes, Upper Traps? Supraclavicular retraction? d. Breathing pattern: is diaphragm working? Belly should move out with resting inspiration. e. Cough and sputum production: document productive or non-productive cough. Document color, viscosity, odor, and amount (teaspoons) of sputum 8. Palpation f. Chest wall compliance (flexibility) g. Mediastinum contents: Task: Mediastinal shift? This would be indicated by a deviation of the trachea to one side. Exam by bending head forward for slack and use 2nd and 3rd fingers to lightly trace along trachea (careful not to over-massage and trigger a vasovagal response in the carotid bodies). Coffman syllabus p.21 h. Chest wall motion (symmetry, superior vs. A/P & Lat motion) Task: Place thumbs (while slightly gathering the skin) at the following positions: mid sternum, xiphoid (thumbs horizontal), and posteriorly at T8 level Task: Inspiration Girth Measurement: tape measure placed around chest at: axilla, xiphoid, lower costal margin. Patient performs maximal expiration, then max inspiration. Normal = 2-3” or 68cm i. Task: Tactile fremitus: vibration from chest wall during speech. Patient says “99”. If vibration feels stronger over a given area it may indicate consolidation: pneumonia, atelectasis j. Task: Scalene muscle action (upward movement of first rib) Hypertrophy? First find both parts of SCM, (elbow must be resting on desk to relax muscles). Lateral to the clavicular portion of the SCM are Scalenes. Palpate inferiorly toward the attachment at the first rib. Try alternating belly breath with upper chest breath. Make a very rapid inhale while palpating. k. Chest wall pain (differentiate cardiac from intercostals, pleurisy) i. Intercostal m. pain = pain with respiration cycle; unilateral splinting, tender to palpation, stretching, worse with deep breath ii. Parietal plurae innervated by intercostal n (referred to chest wall) Pleural inflammation, pleurisy, causes dyspnea and “stabbing” pain on affected side with breath cycle, restricted breathing on the affected side with splinting. iii. Angina: usually related to aerobically taxing activity, however a big meal, or emotional stressors can also trigger. Stable angina (predictable at a certain MET level / activity level) vs. unstable angina (pre-infaction). iv. Liver, gall bladder problems can refer to the R shoulder v. Goodman’s “3 Ps”: Chest pain is likely to be angina if PALPATION has no effect; POSITION changing has no effect; PLEURAL signs are present, i.e. worse with a deep inspiration 9. Auscultation: Coffman syllabus p.4 Hillegass p.625 Be sure bell is “clicked”. Ear tips point to the front. Go under clothing. l. Normal vs. adventitious sounds with respiratory cycle m. Transmitted voice sounds: Bronchophony: “99” clearly audible; Egophony: “e” sounds like “a”; Whispered Pectoriloquy: whispered “99” is audible n. Listen particularly to lung bases posteriorly (early clue to pneumonia, CHF exacerbation) Page 2 of 5 o. Tracheal, bronchovesicular, vesicular sounds (all in the right places!) The anterior and apical segments of the upper lobe might sound louder. That is because you are picking up bronchial or possibly tracheal sounds. In reality these segments have the poorest ventilation p. Don’t auscultate over the scapula, (for the posterior segment of the upper lobe). Have patient slump so scapula move laterally to expose it. 10. Mediate Percussion q. Task: Finger tip(s) on intercostals space and then tap fingertip(s) with 1-2 fingers of opposite hand r. Four normal sounds: resonant (lung), dull (heart), flat (liver or spleen), tympanic (gas bubble in fundus of stomach) s. Task: with subject prone, mark the excursion of the diaphragm at: highest (relaxed breathing) and at its lowest level (maximal inhalation and hold). Normal excursion is1-2”. Diaphragm is slightly higher on the R, over the liver. E. Intervention: Breathing Retraining a. What, why, and who b. What is Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)? Conditions that cause air trapping and an inability to fully expire gases = Obstructive, COPD: Diaphragm is flattened and contracted; external intercostals are shortened. Ribs flare and the AP diameter is increased c. What is Restrictive Lung Disease (RLD)? Conditions that limit the volume of air able to be inspired = Restrictive, RLD. Decreased Tidal Volume. Decreased chest wall compliance (chest wall is stiffer) 11. Diaphragmatic Breathing Training a. Dechman (2004). A review of 22 studies on Pursed Lip Breathing (PLB) and Diaphragmatic Breathing (DB) concluded that PLB helps COPD, but that DB doesn't help COPD. Dechman (2004). Evidence Underlying Breathing Retraining in People With Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Physical Therapy, 84(12), 1189-1197. b. Evidence shows that Diaphragmatic Breathing (DB) slows RR, but does not change VO2. Kisner & Colby 4th ed. p.750 c. Goal: relax accessory mm; decrease the work of breathing (WOB); use during postural drainage; use with post operative patients to prevent pneumonia; use with an anxious person to help relax d. Method: 1. Positioning: semi fowlers, or supine with knees flexed 2. Pursed lip breathing helps slow down expiration. Careful not to force expiration, as that can cause turbulence and bronchiole constriction (and also contraction of the abdominals). 3. Focus on movement below rib cage 4. Hints: hand placement on tummy can give feedback as diaphragm descends, and hand rises, during the inspiration. a. A tangent: weights on the abdomen, for a patient with a SCI, to give resistance to the descent of the diaphragm (by weighting the viscera) during inspiration is not well established, and is not considered best practice There is a risk of inadvertently teaching a paradoxical breathing pattern since the weight might activate the abdominals to contract during inspiration – when they should be relaxed! e. Progression: start in a semi-Fowler position, then progress to: 1. hooklying, 2. sitting, 3. standing, 4. walking 5. stairs (try paced breathing with a stop and rest) 12. Pursed Lip Breathing (PLB): Evidence indicates it decreases dyspnea, and increases gas exchange. Most persons with COPD learn this naturally as a coping mechanism, but not all do, so you may need to instruct the Page 3 of 5 person. In the early stages of a chronic disease, PLB may only be necessary as a coping mechanism during aerobically taxing activities. 13. Paced Breathing: Normal I:E ratio is 1:2. With COPD the ratio is often 1:3, 1:4 because of a lengthening of the expiration time (with pursed lips) to attempt to increase expiratory volume. Consider functional applications of this breathing rhythm. a. Walking rhythm: Inhale on “one-two”; Exhale on “three-four-five-six-seven…” b. Incorporate PNF patterns (inspiration on UE D-2 flexion, then longer expiration/rest with expiration) c. PACED BREATHING + VALSALVA AVOIDANCE + ENERGY CONSERVATION: examples: o Pushing a refrigerator across the floor: (LONG exhale with the pushing exertion) o Rolling up a garden hose: (LONG exhale with the pulling exertion) o 18th century sea shanties sung on clipper ships, were timed to increase sailors’ efficiency as a group d. Use a rest period when necessary by assuming a recovery position: Hillegass p.658 o Leaning forward with arms bearing weight (fixating humeri) on countertop or parking meter o Leaning against a wall in a slouched, flexed position o Sitting with elbows on knees “professorial position” 14. Segmental Breathing: Performed on a segment of lung, or a section of chest wall that needs increased ventilation or movement, e.g. post thoracotomy, trauma to chest wall, pneumonia, post mastectomy scar, post chest radiation-fibrosis. Use of imagery is helpful. a. Lateral and lower costal: therapist (or patient’s) hands are placed on restricted area and patient instructed to “send your breath down here”, or “fill up this area with your breathing”. b. Upper lobe, anterior and apical segments (fingers placed below or above clavicle) c. PNF Facilitation Technique: gently push in during expiration, then a quick stretch (quickly pushing in just a bit further), just before the start of inspiration d. Use a towel or belt for resistance around the lower ribs to “breath into” e. Soft tissue stretching: elevate UE and sidebend the trunk away from the restricted segment, during expiration. 15. Chest Wall mobilization / Stretching Especially useful for patients with SCI and resulting Restrictive Lung Disease (RLD). Thoracic spasticity can stiffen (decrease compliance) of chest wall. 16. Glossopharyngeal Breathing : A safety skill in the event of power failure for a person who uses a ventilator (part time) F. Intervention: Secretion Management / Airway Clearance Techniques 17. Huff coughing: is performed by forcefully exhaling through an open airway after taking in a fairly large inspiration. You take in a slow, deep breath and hold this breath for a count of three. You then perform short, quick, forced exhalations with your airways open. Say the word “Huff” during the exhalation. Younger children may be taught to flap their arms to the sides of their chests as they perform the “huff” cough. This technique is sometimes referred to as the “chicken breath”. This activity may help the child to focus on the forced exhalation and add enjoyment to the technique. Huff coughing may not be appropriate for the person with advanced COPD, because a sustained maximal inspiration (SMI) followed by forceful expiration can cause excessive airway turbulence and secondarily cause bronchoconstriction and more air trapping. Consider autogenic drainage or active cycle of breathing techniques in that case (below). Abdominal strengthening (T5-T12 innervation) for a patient with a SCI, can be useful for generating a more forceful expiration and therefore a more effective cough, improving their airway protection! If a person is just being weaned from a ventilator, blowing out a small “puff” will begin to trigger abdominal contraction, and a mirror can be put under the mouth for feedback. Page 4 of 5 18. Self-Assisted cough: Heimlich-type maneuver with patient’s hands doubled over abdomen and pulling in during Huff. Splinting before coughing: for the post op thoracotomy patient. Squeeze pillow to the area; wrap towel around abdomen; do a “self hug” before a sneeze. 19. Active Cycle of Breathing Technique (ACBT) Hillegass p.653, or O'Sullivan 5th ed. p.581. 20. Autogenic Drainage - as described by Frownfelter Schoni (1989) “The first phase starts with a normal inspiration and is followed by a breath hold to ensure equal filling of lung segments by collateral filling; then a deep exhalation is made into the expiratory reserve volume range. By lowering the middle tidal volume below the functional residual capacity level, secretions from peripheral lung regions are mobilized by the compression of peripheral alveolar ducts. Midexpiratory tidal volume is lowered in the range of normal expiratory reserve volume. The second phase of AD consists of tidal volume breathing so that breathing is changed gradually from the expiratory reserve volume into the inspiratory reserve volume range, which mobilizes secretions from the apical parts of the lungs. The velocity of the airflow must be adjusted at each level of inspiration so that the maximal expiratory airflow is reached without being high enough to cause collapse of the airways. Flow volume curves show that higher flows of longer duration can be achieved with AD (Dab, 1979), demonstrating that mucus can be moved farther and at a fast rate. The third phase consists of deeper inspiration into the inspiratory reserve volume, with huffing often used to help in evacuating the mobilized secretions. Control of airflow during this final phase is essential to the avoidance of uncontrolled, unproductive coughing.” Frownfelter, D., Dean, E. (2006). Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physical Therapy – Evidence in Practice. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier. p.329 MSH_EP MUPT 04,06,08 Page 5 of 5