That`s Keats`s phrase for Wordsworth, where everything relates to

advertisement

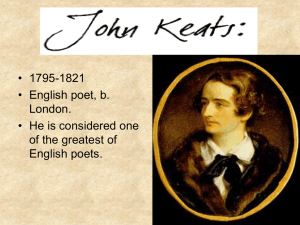

KEATS STUDY GUIDE This guide introduces you to some key concepts for understanding Keats’s poetry in general and “Ode on a Grecian Urn” in particular. John Keats (along with Percy Shelley and Lord Byron) is referred to as a “second generation” Romantic poet. (Blake, Wordsworth, and Coleridge make up the so-called “first generation.”) The second generation writers tend to be more skeptical and philosophically ironic. They are more dubious, for example, about a Wordsworthian “spirit that rolls through all things.” In Keats’s case, this second-generation skepticism also applies to the poet’s ego. Keats felt that Wordsworth was too “self focused,” too consumed by the quest of the subjective self trying to wed with Nature and the “spirit that rolls through all things.” For Keats, any “epiphany” or visionary “spot of time” could only come about by way of what he called “negative capability,” which involves the erasure of self to experience the potent otherness of the world. Keats is not arguing that we should completely discount the self, and never have personal convictions. He’s not saying that we should just let ourselves roam without any direction. He’s not arguing that we should constantly change in fundamental ways, such as one week we believe in God, then we become atheists, then Buddhists, and so on. Instead, he’s arguing that truth is no longer fixed or universal or absolute. All we have is experience. And for Keats (and the Romantics in general) we must continue to be open to experience. We can’t do that if we’ve got all sorts of fixed ideas. That is what Keats means by “negative capability.” We do need philosophies, codes, world views—we have to have those things to survive. But we also have to be able to suspend them, because they are filtering models. They can only tell us what we put into them to begin with. They can therefore keep us, according to Keats, from seeing something new. That’s what Browning’s dramatic monologues (like “My Last Duchess”) are all about. To understand one of his characters we have to suspend our own egos—what we are—and become that character. In the end, we become ourselves again, but our ego, our sense of self, all that makes us a particular identity, changes from an in-depth “empathetic understanding” of the other. So Keats’s ideal of “negative capability” has to do with suspending the ego, the subjective identity, and becoming something else. That’s a process, and process is a watchword for the Romantics. For Keats, the truest way of life is one that is elastic and process-based. He is trying to get away from system, because system will limit information and therefore limit understanding. For Keats, we have to suspend whatever it is that makes us a self or an ego. That’s why, for Keats, the poet is the most “unpoetical” of all things. He has no self. He is always becoming another being—a nightingale, a Grecian urn. Eliot was in many ways a Keatsian poet of negative capability. He eschewed the overly personal or confessional in poetry. He suspended the self, the personal— filtering it through figures like Prufrock. This world, according to Keats, is not a vale of tears, a valley of suffering before the final redemption through Christ or through nature or through some Wordsworthian spirit that rolls through all things. That’s wrong, as far as Keats is concerned. Rather, human existence is a “vale of soul-making.” Life can’t redeem us. We can redeem life. Nature doesn’t have the answer. Nature becomes the occasion for understanding that the answer lies within us. The second generation poets are finding ways of letting go of God, which the first generation weren’t ready to do. Take a look at J. Hillis Miller’s book The Disappearance of God—the “disappearance” begins here in the second-generation Romantics. Wordsworth still has the hope that the landscape can be divine. When we get to Victorians like Matthew Arnold and Alfred Lord Tennyson, we see that they can’t believe this any longer. For them, nature symbolizes the peace and beauty possible in human existence, but it has no metaphysical implication or higher significance. Arnold writes “where nature ends, man begins.” Byron, Keats and Shelley fall in between the first generation Romantics (Blake, Wordsworth, and Coleridge) and the major Victorians (Tennyson, Arnold, and Browning). These second-generation Romantics can’t believe in a “genius loci,” a spirit of the place. For Keats, nature is beauty, a reminder of a classical world that once was, but Nature is not divine, as it is for Wordsworth. Yet Keats has not yet reached the sort of social or more existential vision that Arnold, Tennyson, and Browning exhibit. A despair about the fleetingness of visionary experience and beauty is found in the firstgeneration poets, but not with quite the same degree of skepticism or even pessimism that we see in the second-generation poets. You can find evidence in Wordsworth’s poetry of Romantic irony and doubt, but his works are not ultimately skeptical. It’s quite the contrary with Shelley and Keats and Byron. It is tough to think of three poets more different than Byron, Shelley, and Keats in terms of their basic temperaments. They are linked by the Zeitgeist, by skepticism, and therefore by the notion that process and aspiration are of central importance, rather than some central truth that can be pronounced. But in terms of their individual temperaments and personalities, the three are extremely different. One way to find one’s humanity and to fulfill desire is to surrender to passion, to some kind of Blakean daemonic energy, to the ecstatic sublime. That’s what Keats’s poetry is often about. Keats once wrote: “Oh for a life of sensations, rather than thought.” Then there is also Keats the aesthete, a tutelary genius for the pre-Raphaelite poets. Those who founded the “art for art’s sake” movement—the Rossettis, Pater, Swinburne—looked to Keats as their model. Negation of the self is only the first step for Keats, however: you negate those things that make you an ego. But the crucial next step is that then you become aware that these sorts of experiences are mysteries and uncertainties. For Keats, if we deal with life experiences and the objects and beings of the world using fact and reason, then we distort them. Keats once said that he got inside a billiard ball to such an extent that he could actually feel its roundness. For Keats it’s all about sensual and ecstatic identification. In “My Last Duchess,” the easy thing to do is make a moral judgment: the speaker is evil because he had his wife killed. But if it’s that simple, then why write the poem, and why read it? What’s interesting is to enter into the Duke’s mind. Our doing this doesn’t make him not evil, but it allows us to consider—well, is he insane? Or is he someone who views his wife as a piece of art? There is a danger of course. Once you start to historicize a situation, once you start to psychologize a human being, it does run the risk of moral relativism (where any immoral behavior is excusable because the evil is linked to understandable underlying causes). It doesn’t have to come to moral relativism, but the threat is clearly there. So we have to beware of pure relativism, because we may dupe ourselves into perpetrating or maintaining or legitimating or excusing brutal oppressions and exercises of violence. For Keats, we have to have agility—we have to be able to see it both ways. One could argue that people who don’t do so because of the fear of perplexity and paradox. But there’s also the possibility that they don’t embrace ambiguity because they are so (problematically) confident about who and what they are. Clearly, we have to have models to function and live. But models can only tell us what we program them to tell us. Keats’s point is that there is no model that can be programmed in an imaginative way that will allow us to understand the kinds of questions he wants to explore. So we have to suspend those models, so that we can be completely open to experience in all of its intensity, richness, complexity, and ambiguity. When it’s over, we’ve got to put the model back on and act. But that’s at the end. What he’s often left with is not the answer but the question. In his letters on negative capability, Keats claims something similar to Eliot’s point in “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Eliot is arguing against personality, and saying that the personality of the poet is certainly involved but it’s involved primarily as a catalyst. If you look at the residue of the chemical interaction that takes place, it’s the poem; you don’t find any trace of the poet’s personality there because he’s found an “objective correlative”—an image or scene or figure that stands in and “correlates” to the poet’s personality or feelings or ideas. The poet’s “real,” everyday personality never gets represented directly. Keats’s point seems to be very similar here because he goes on to say that writers of genius don’t have any individuality. Even in early letters Keats is thinking about personality, individuality and the way in which that is very different from the quality of mind that goes to make up a genius imagination. What’s he’s trying to do is become one with the thing he contemplates, to imaginatively enter into its life, rather than to think about what he thinks about it. So that’s the first part of negative capability: negating one’s own ego, personality, identity, in order to see things from the perspective of the other person or thing or situation. According to Keats, geniuses don’t use their strong identity in a moment of creation; they’re more like the “chameleon.” Everything in Wordsworth, everything, is filtered through his personality, his needs, his memories, his feelings. Keats has a different vision of the poet’s character or self: “it is not itself, it has no self, it is everything and nothing. It has no character.” Wordsworth, in Keats’s mind, is also the “virtuous philosopher” poet. Keats’s ideal is the chameleon poet, becoming what we imagine, taking on the character of someone else or some situation. Keats admires a philosophical disinterestedness. That’s really what he’s talking about—disinterestedness, open-ended speculation without a priori moral judgments or explanatory models. Again, he writes, “A poet is the most unpoetical of anything in existence.” In his letters about the chameleon poet, Keats begins to develop his idea of negative capability. But he’s still only at the beginning—negating his own personality, with the exception of his advocacy of speculation. But then the negative capability letter itself (To George and Tom Keats, Dec. 21-27, 1817) he says that “it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature & which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason . . . Coleridge, for instance [was] incapable of remaining content with half-knowledge.” So here is the proper model for Keats—not Wordsworth or Coleridge, but Shakespeare. Keats is taking Shakespeare as his great ideal. Ultimately, Keats begins to want to combine what he values of the poetry of the past—Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare, which is poetry that has great power and scope—with what he admires in his contemporary poets, their inwardness and psychological explorations. Eventually, too, he starts to rethink Wordsworth, and he tries to decide who was the greater poet, Wordsworth or Milton. In looking at Keats’s famous “Odes,” try to think about imaginative ascent and descent. The scholar Jack Stillinger claims that the Keatsian speaker always begins in the world of actuality, takes off on a flight of imagination, but then—either because there’s something lacking in the object he’s meditating on, or because there’s some problem in maintaining the meditation—the flight returns to earth and again with questions. Walter Jackson Bate maintains that what these poems dramatize is the “greeting of the spirit with its object.” Many readers see Romanticism being about an attempt to overcome the split between subject and object through meditation. Another critic uses the phrase “lyrics of symbolic debate.” Think about the Romantic poets and what is most distinctive about them. Wordsworth is interested in nature as it is colored by memory. With Keats, it’s the skeptical perspective that critics characterize with the words “debate” and “drama.” That’s perhaps most central. The other thing that is truer of Keats than the others is the sense in which he uses a particular symbol to organize the poem. In Wordsworth, there are passages in poems that focus on a symbol, but it’s the concreteness of an object that often makes a poem distinctively Keatsian. Keats’s approach to a symbol in a poem reveals his desire to see if that symbol is commensurate with the imagination in its “stepping towards a truth” (that’s Keats’s phrase). Using negative capability, Keats causes the object to become an objective correlative—a correlate to a specific emotional or psychological state. Keats is different from Wordsworth, who is more subjective and personality driven. Keats is trying to find an objective correlative, and so he negates his own personality (whatever it is in his personally that’s driving him—whether it’s tuberculosis, the death of his brother, his own worries, and so on). He tries to negate that and sympathetically approach the symbol, the object. He tries to capture something in all of its concreteness, particularity, ambiguity, and he uses the symbol as a field in which opposing attitudes can engage. What Keats affirms at the end is the spirit, the symbol, the process. He doesn’t want to dissolve the mysteries, the uncertainties that are crucial to that experience, process, and symbol. He is always being skeptical, open-ended, contemplating the variety of ways of looking at an object. In the “Ode on a Grecian Urn” the entire poem focuses on the urn. It’s almost as if Keats is holding an urn in his hands and turning it; it’s there from beginning to end. There is a drama between perception and object, but that’s the controlling form of the whole poem. In the case of the urn, he starts with the work of art itself, and his question is: Can art provide some system of salvation? He’s never sure. To help yourself understand the concreteness and aestheticism of Keats, think about the way in which Keats becomes an important figure later in the nineteenth century, especially for the “preRaphaelites, who believed in “art for art’s sake.” We haven’t read anything by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, or his sister Christina Rossetti, or Charles Algernon Swinburne, but these poets are interested in the beautiful object. We’re talking about the height of the Industrial Revolution and materialistic society; these artists wanted to protect the beauty of art from that kind of crass world. When they looked for inspiration, Keats was one of their major figures. They were interested in beauty, in art as a religion. Here is the sense of art as ritual, of art as something that kept alive certain human sensibilities and emotions. The pre-Raphaelites were also interested in the Keats of “dreamy escapism.” In one letter, Keats says, “what the imagination seizes as beauty must be true.” This is something scholars point to as they try to make sense of Keats’s evolving concept of the imagination. This is definitely something else that the pre-Raphaelites would have found very congenial. Later, Keats says, “Oh, for a life of sensation rather than thoughts.” This can be viewed as Keats celebrating a kind of empiricism. But also, as in “Ode to a Nightingale,” there’s a more philosophical interpretation possible. In the famous “negative capability” letter, he says “the excellence of every art is its intensity, capable of making all disagreeables evaporate . . . being in close relationship with beauty and truth.” So there is always this emphasis on intensity, on concrete, sensual pleasure in Keats. Romanticism was for many years defined as the age of feeling as opposed to the age of reason. For Keats, that is the way to truth and beauty, through the intensity of response to an object. Always remember Keats the esthete, Keats the poet who pursues the ideal by positing a separation between the world of mutability and the world of visionary imagination. Keats wants the power, the scope and scale of the great classical writers like Homer and Virgil, but he admires the inward, searching nature of his contemporaries. So he starts to rethink Wordsworth. Wordsworth has been set up as the model of the poet of egotistical sublime, as opposed to the Keatsian chameleon poet. So we have to keep in mind Keats’s re-evaluation of Wordsworth. In a way, his re-evaluation embodies his own negative capability; he ends up looking at Wordsworth and holding competing and even contradictory notions in his mind at the same time. His earlier views about Wordsworth tend to be negative, his later views positive. In a letter written in 1818, Keats uses the word schweben, “hovering,” between luxuriance and a love of philosophy, between an exquisite sense of luxuriant amassing of sensuous pleasure, and philosophical speculation. Here is Keats beginning to think about truth not necessarily as something equivalent to beauty, but as having something to do with knowledge and philosophy. For Keats, the whole purpose of life is that it’s an opportunity to create a soul or an identity. Morse Peckham argues that the Christian view is that life redeems us—we’re given grace. The thrust of Keats’s “vale of soul-making” is almost the reverse: that we can redeem life, give it value and meaning if we see it not as a vale of tears, but as a vale of soul-making. For Keats this is something far more active and creative than a kind of stoical acceptance of suffering, waiting for atonement, and so forth. So “negative capability” and the “vale of soul-making” are not antithetical notions: negative capability refers to the act of poetic composition; for a poet to create as richly and freely as he or she desires, it is necessary to get beyond the limits of ego and personality to see a thing from multiple points of view. With his “vale of soul-making” idea, Keats is not talking about writing poetry, but about every human being. It’s somewhat similar to the Lockean idea of the tabula rasa. But it’s also similar to the more organic view of human life and the cosmos that find in Romantic art. It’s similar to Wordsworth’s growth the poet’s mind. This is Keats’s idea of the growth of the human mind. So he’s throwing off the Christian system of salvation in favor of a more existentialist one. Rarely, but often enough to make a profound impact, there may come in an imaginative life Wordsworthian spots of time, or visionary experiences. This may come for Keats through meditating on the nightingale’s song, or from turning the Grecian urn in his mind. Keats begins with the moment of experience, that triggers thought, feeling, memory, intuition, and those working somehow together constitute the imagination. Keats’s letters are remarkable. They capture someone debating with himself. What does it mean to be a poet, writing at this particular time in the history of the world? He talks about the advance of the age. He has something of a sense of an aesthetic revolution. He’s grappling, debating with all sorts of notions about where he’s going to go as a poet. And he is shadowed by thoughts of mortality, a sense of knowing that he is going to die (Keats died at an early age from tuberculosis). In Keats, there is still the possibility of a world in which imagination, feeling and love can bring renewal. And that is what Romantic art in one sense is all about. ODE ON A GRECIAN URN I. Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme: What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape Of dieties or mortals, or of both, In Tempe or the dales of Arcady? What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy? II. Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but more endear’d, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare; Bold lover, never, never canst thou kiss, Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve; She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair! III. Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu; And, happy melodist, unwearied, For ever piping songs for ever new; More happy love! more happy, happy love! For ever warm and still to be enjoy’d, Forever panting, and for ever young; All breathing human passion far above, That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy’d, A burning forehead, and a parched tongue. IV. Who are these coming to the sacrifice? To what green altar, O mysterious priest, Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies, And all her silken flanks with Garlands drest? What little town by river or sea shore, Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel, Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn? And, little town, thy streets for evermore Will silent be; and not a soul to tell Why thou art desolate, can e’er return. V. O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede Of marble men and maidens overwrought, With forest branches and the trodden weed; Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral! When old age shall this generation waste, Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,”—that is all ye know On earth, and all ye need to know. From Romantic Irony by Anne Mellor: In “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” Keats again poses the romantic delights of an idyllic world, now identified with the deathless realm of art, against the skeptical consciousness of human pain and mortality. Here the debate focuses on the value of art itself rather than on the possibility of unselfconsciousness or lack of irony. Because the urn is static and visible, the poet can greet it directly, fully enter its life, and explore all its dimensions exhaustively. But even as the poet approaches the urn, he is aware of its limitations: it is beautiful, but “unravish’d”—a bride who has not known the ecstasy of sexual consummation. And while the proverb has it that “Truth is the daughter of time,” this urn is but a “foster-child” of time, not a direct descendant from truth. The urn is only a “sylvan” historian, a teller of pastoral tales whose knowledge is thus provincial and incomplete. Nonetheless, the urn’s beauty is compelling to the poet’s empathic capacities; and he eagerly enters into the world depicted on its shape. Asking increasingly urgent questions that record his intensifying involvement in the life of these “men or gods” (who only in the eternal realm of art are indistinguishable), the poet comes to fully apprehend and appreciate the “sweeter” melodies of the pure imagination, uncorrupted by the limitations of human musicians, and the never-ceasing pleasure and beauty of a passionate love “Forever warm and still to be enjoy’d, For ever panting, and for ever young.” But even as he enthusiastically delights in the perfection of ever-green boughs, ever-new songs, and ever-intense erotic love, he is ironically aware of the distance between such perfect happiness (which is all the more perfect for being anticipated rather than disappointingly realized) and a mortal world where leaves are shed, melodists grow weary, and “breathing human passion leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy’d.” Having perplexed his enthusiastic delight in the urn’s enduring beauty with his ironic appreciation of a human love that is both consummated and destroyed, the poet turns back to the urn with questions predicated, no longer on the assumption that the figures depicted on the urn are gods, but on the assumption of a shared finite humanity. “Who are these” people? “What little town” did they come from? And now that he sees the urn’s figures as human beings rather than as perfect, immortal deities, the poet can see them only as dead, lost in history. “Little town, thy streets for evermore / Will silent be; and not a soul to tell / Why thou art desolate, can e’er return.” And now the urn seems to the poet no longer a living world populated by intensely happy trees, lovers, and musicians but simply an object, an “Attic shape” whose “fair attitude” is as posed and artificial as Lady Emma Hamilton’s legendary Attitudes. As Schlegel said, “The play of communicating and approaching is the business and the force of life; absolute perfection exists only in death” (DP, 54). And yet this Cold Pastoral has the capacity, even if only for a single moment, to “tease us out of thought,” to do us the service of ultimate good friendship and release us, however briefly, from our ironic consciousness of mortal limits. And because the urn, the masterful work of art, has this power to lift man out of self-consciousness, to make him conscious instead of how it feels to live in a world of perfect beauty, perpetual spring, always passionate love, it has earned the right to display its aphoristic, “leaf-fring’d” legend or inscription. Responding to the poet’s questions, the urn at last enters the debate and speaks: “Beauty is Truth,—Truth Beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” In the realm of art, beauty and truth can fully unite; there, “what the imagination seizes as beauty must be truth,” for only what is beautiful has absolute aesthetic validity. And from the point of view of the work of art, aesthetic criteria are all that exist: “That is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Since these aesthetic values can bring intense and undeniable pleasure to men and women—the vicarious experience of eternal delight—they are indeed “friends” who must be cherished. But the poem has posed these aesthetic or romantic values of beauty and stasis against another set of values, the ironic truth of a human existence consummated in time. In this realm where death incites the agonies and strife of human hearts, neither love nor beauty lasts; beauty can be only skin-deep; and the truth can be ugly. In this poem’s delicate balancing of two opposed realities, the urn’s final statement both is and is not true.