Abstract Dietary minerals are essential parts of a human diet

advertisement

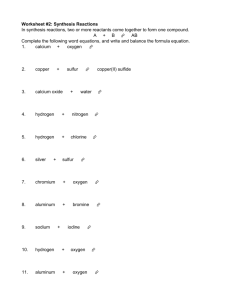

Abstract Dietary minerals are essential parts of a human diet. Although the most well-known source of recommended values for dietary minerals are the RDAs, they do not necessarily reflect new research proposing potential subtle and long-term benefits to extra mineral supplementation beyond the levels in a normal human diet. Therefore, it is worth examining optimal mineral levels in more details. Most of the research on dietary minerals is low-quality and probably represents spurious findings. When these are compared to contradictory evidence and high quality RCTs and meta-analyses are given preference, only a few minerals continue to show benefits when optimized beyond the level implicit in a healthy diet. Sodium is widely agreed to cause hypertension, and should be kept as low as possible, preferably below 1.5g daily. Potassium is protective against hypertension and most diets are deficient; although supplementation is difficult various dietary strategies are possible to increase it to a recommended level of 4.7g daily. Women may wish to supplement their iodine intake to 6 mg/day to prevent breast cancer. Lithium supplementation is still experimental and poorly studied, but the benefits of a small dose of 1 mg seems worth the risk. Magnesium and selenium are border cases in which the evidence does not quite support supplementation, but especially interested individuals may wish to read up on them in more depth. There are minimal projected benefits from optimizing levels of other minerals. Recommendations All minerals as normally obtained from a balanced diet except: SODIUM: < 1.5 g through dietary control POTASSIUM: > 4.7g through diet supplemented by potassium salt if necessary IODINE: + 6 mg supplement for women as Lugol's solution or other molecular iodine LITHIUM: + 1 mg supplement as lithium orotate Introduction The human body is primarily composed of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and hydrogen, which along with the much less common sulfur form the major building blocks of large organic molecules like proteins and carbohydrates. However, some organic molecules and processes require additional elements. About sixteen elements are absolutely necessary for life [1], but optimal functioning requires several more. Some of these elements can be obtained from the breakdown of macronutrients; the others must be obtained separately in the diet and are called the essential dietary minerals. There is no universal agreement on which dietary minerals are essential. The government's Institute of Medicine focuses on twelve [2]: calcium, chromium, copper, fluoride, iodine, iron, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, phosphorous, selenium, zinc. The Linus Pauling Institute [3], a leader in nutrition research, adds two others: potassium and sodium. In substance, these lists are identical: sodium and potassium were excluded from the IoM list only because they were classified as “electrolytes” rather than minerals, not because of any question as to their importance; these fourteen are the closest thing to an accepted list. Other sources speculate on the possible importance of vanadium, arsenic, silicon, and others, but there is as yet no convincing evidence of their importance [4]. Deficiencies of essential dietary minerals can cause symptoms ranging from subclinical malaise to serious disease; excess of these minerals can cause various forms of toxicity. As a result, there is widespread medical interest in the proper dietary levels of these minerals, and in the potential effects of supplementation. The largest and most rigorous attempt to set these levels is the Institute of Medicine's Dietary Reference Intakes, most commonly encountered as the RDAs seen on food products. The RDA of a mineral is defined as the amount which should “meet the nutrient requirement of 97-98% of healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group.” [4]. Researchers can use multiple different methods to calculate an RDA. In some cases, researchers calculate an RDA by examining the amount of the mineral lost each day in urine, sweat, et cetera, and choosing a value that is most likely to produce a neutral mineral balance in the body. In others, they compare dietary intake of a mineral to some clinical reference value affected by the mineral: for example, since dietary potassium affects the levels of serum potassium, they determine what levels of dietary potassium are most likely to cause a healthy level of serum potassium; here healthy values of serum potassium have already been set by previous studies, since serum potassium is much easier to measure than dietary intake. In still other cases, they will measure the activity of an enzyme that depends on the mineral; for example, the RDA of selenium is based on the amount needed to bring activity of the selenium-based glutathione peroxidase enzyme to its plateau value [5]. In the most robust RDAs, researchers test several or all of these methods and establish a value only when they find them to be broadly in agreement. In cases where an RDA cannot be established, researchers determine an AI, or Adequate Intake. AIs usually represent a level equal to or somewhat higher than the average observed among a population who eat a balanced diet and show no clear signs of mineral deficiency. Finally, the Dietary Reference Intakes often include a Tolerable Upper Intake Level, "the highest level of daily nutrient intake that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects for almost all individuals in the general population". [4]. In the best cases, these levels are obtained after having observed the level of adverse effects at different levels of intake. In cases where such data is not available, they may be obtained through animal models or through measurement of mineral accumulation in the body. The Dietary Reference Intakes set the gold standard for recommended quantities of essential minerals in the diet, but they have only the very modest goals of avoiding overt clinical deficiencies. Recent medical research has included several startling claims that extra supplementation of minerals beyond the levels necessary to meet the DRIs has unexpected positive effects, including the prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. These claims generally remain controversial, but if true would imply a benefit to mineral intake in excess of the DRIs and other commonly used guidelines. This necessitates a closer examination of the costs and benefits of each. This analysis will begin with the DRIs for each mineral, with special emphasis on whether the average Western diet can be expected to satisfy those values. It will continue to discussion on proposed benefits of an intake above (or in some cases like sodium, below) the DRI, and whether or not the evidence for these proposed benefits reach statistical and clinical significance. Finally, if it determines that there is a clinically significant positive effect of an intake level significantly above or below the level commonly encountered in the diet, it will conclude with a discussion of whether supplementation is cost-effective and whether it poses any potential risks of its own. To some degree, examining the cost-effectiveness of mineral supplementation a purely academic exercise. Many people who supplement their diet do so through a multivitamin containing multiple minerals. This makes an analysis of the dollar cost per life saved of, for example, selenium versus zinc supplementation somewhat moot; most people would be buying neither selenium pills nor zinc pills, but a multivitamin containing both. Examining the costs and benefits of multivitamins might prove a more practical exercise, but contains its own pitfalls: a multivitamin might contain both helpful and harmful substances. This is further complicated by the consistent failure of studies to show any benefit whatsoever from multivitamins [6, 7]. Because of these limitations, this analysis will discuss costeffectiveness recommendations on the basis of individual minerals, while keeping in mind that this may overstate the financial costs relative to those of a multivitamin. This analysis suffers from several potential limitations. First and foremost is the confused state of most evidence relating to the benefits of dietary minerals. This confusion is in most cases due not to an absence of studies, but to a profusion of studies with contradictory results. Where possible, this analysis has tried to examine the largest studies or systematic reviews or meta-analyses of all studies. It has also relied heavily upon the judgment of the Cochrane Collaboration, widely considered the world leader in meta-analysis A more fundamental limitation is the limits of quantifiability itself. Some minerals may make people feel healthier, give them more energy, or improve their mood. Although this is quantifiable in principle, and in some cases even relates to easily quantifiable end points like depression diagnoses or suicide, in general very little research has been done in the area and that which has been done is hard to trust. Therefore, this analysis focuses on more easily quantifiable end points such as health maintenance and disease prevention. Calcium The AI of calcium for adults age 19-50 is 1000 mg; the TUL is 2500 mg. This number was set because it was between the 50th and 75th percentile of calcium intake in healthy men, and the 90th and 95th percentile of calcium intake in healthy women. [8]; it also approximates the intake necessary to achieve a calcium balance supporting normal bone accretion. Mean calcium intake in the United States is 871 to 1,266 mg/day in men and 748 to 968 mg/day in women; although the diets of children and the elderly are often deficient in calcium, most adults 19-50 consume around the AI or above. [8, 9] Proponents of calcium supplementation point to studies suggesting it may decrease the risk of osteoporosis and colon cancer later in life as well as treat hypertension. Indeed, one recent observational study suggested that calcium could decrease all-cause mortality [10], though the study's own authors cautioned against taking this correlational evidence too seriously. However, other studies suggest calcium can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and prostate cancer. Calcium prevents osteoporosis. When combined with Vitamin D, calcium supplements can decrease fracture risk in elderly populations by up to 40%; this effect is greater than that of Vitamin D alone . Premenopausal women and younger men are at low osteoporotic fracture risk. [11] Calcium probably prevents colon cancer [12]. In the Calcium Polyp Prevention Study, subjects who took a 1200 mg calcium supplement daily cut their risk of adenoma, a precursor of colon cancer, by a statistically significant 15%. But a subsequent study, while confirming the finding, found that extra calcium beyond the first 700 mg daily had no added protective effect [13], implying no benefit to amounts of calcium beyond those common in an average diet. Some studies have found an inverse relationship between calcium intake and hypertension. For example, in the Women's Health Study, those in the highest quintile of calcium intake had a relative hypertension risk of only .89 that of those in the lowest quintile. [14]. However, subsequent studies and meta-analyses have failed to confirm this finding. The Cochrane Review on Calcium Hypertension analyzed 13 RCTs and found a small but statistically significant effect of calcium supplementation on systolic blood pressure of -2.5 mm Hg, and no significant effect on diastolic pressure. However, many of the studies involved were poor quality and inadequately blinded, and the meta-analysis concluded that "due to poor quality of included trials and heterogeneity between trials, the evidence in favour of causal association between calcium supplementation and blood pressure reduction is weak and is probably due to bias." [15] Some studies have found increased health risks from calcium supplementation. In particular, an RCT associated with the Women's Health Initiative found calcium supplements increased the risk of heart attack and stroke by about 20% each [16]. These results are difficult, since calcium is often taken along with Vitamin D and there are complex interactions between the two. A model in which calcium increases the risk of cardiovascular disease but Vitamin D decreases this effect is both biologically plausible and empirically supported [17]. High calcium diets may increase the risk of prostate cancer. High serum calcium levels can triple prostate cancer risks [18] and a meta-analysis of twelve observational studies found that both dairy consumption and calcium consumption were significantly linked to prostate cancer, with relative risks of 1.11 and 1.39 respectively [19]. Finally, high calcium can increase the risk of kidney stones, constipation, and the neurological symptoms of hypercalcaemia. Although calcium intake during youth can build up bone stores that prevent osteoporosis when younger, these effects seem less pronounced than its possible risks Calcium's effect on hypertension is unclear and possibly nonexistent. Although it probably does prevent colon cancer, calcium levels above those in an average American diet do not have extra protective effect. High calcium intake probably increases the risk of prostate cancer and may increase the risk of heart disease, as well as many medically well-recognized acute symptoms such as kidney stones and digestive complaints. Therefore, healthy adults below the age of fifty who are not at unusually high risk for osteoporosis should aim for a diet including the recommended 1000 mg/day of calcium, but should generally avoid calcium supplements. Those people who do choose to take calcium supplements should take Vitamin D as well. Calcium carbonate is relatively safe and effective except for those who use PPIS, H2 blockers, or have other drugs or conditions decreasing the normal levels of stomach acid; these people may experience fewer digestive effects with calcium citrate. [11]. Chromium The AI of chromium for adults age 19-50 is 35 micrograms/day for men and 25 for women; there is no TUL because chromium is not known to have any toxic effects. The AI was set by examining 22 wellbalanced adult diets and choosing the one with the highest levels of chromium to adjust for likely under-reporting. [5] The average American adult chromium intake is 33 micrograms/day for men and 25 for women [20], although some analyses suggest it may be higher [21]. These numbers are relatively close to the AI and signs of chromium deficiency are extremely rare. Because chromium potentiates the effects of insulin, there has been widespread interest in its use in metabolic conditions such as obesity and diabetes. Pittler et al [22] found evidence of a statistically significant weight loss of about 0.1 kg per week with chromium picolinate supplementation. Three problems mar this result; first, this rate of weight loss is not clinically significant (compare to diets, which can burn 0.5 to 1 kg per week) unless maintained over long periods, and none of the studies in the analysis had a follow-up of more than a few months. Second, the meta-analysis found heterogenous results, with most of the positive findings being sponsored by manufacturers of chromium supplements. Third, an associated funnel plot shows evidence of publication bias. More recent meta-analyses fail to replicate the positive result and find no effect of supplementation [23]. Because chromium potentiates the action of insulin, and type II diabetes is primarily a disease of insulin resistance, there has been interest in the ability of chromium to prevent or reverse diabetes. However, most studies have failed to show an effect of chromium supplementation on glucose control; the only outlier was a study from China which found the supplementation with 1 mg of chromium per day decreased serum glucose by 15-19% in Chinese diabetics. Critics of the study say that results from a Chinese population who are much less obese than American diabetics and who may be chromium deficient to begin with do not generalize well to the western world. [24]. Other studies in diabetics found chromium increased weight gain when taken in conjunction with the sulfonylureas, a commonly prescribed group of antidiabetic drugs. [25] Chromium does not appear to prevent diabetes or decrease weight gain in non-diabetics. [26]. Some case studies have suggested idiosyncratic side effects of chromium supplementation including rhabdomyolysis (a dangerous form of muscle breakdown) and exanthematous pustulosis (a form of rash), but these have not been verified. The evidence that chromium helps people lose weight is shaky, and even if true the effect is probably minimal. Chromium may improve glycemic control in diabetics. but does not itself prevent diabetes. Healthy adults do not need chromium supplementation; there is too little evidence to recommend for or against such supplementation in diabetics, although those who use sulfonylureas may wish to be especially cautious. Chromium picolinate is the most bioavailable form of chromium and probably the preferred form for supplementation. Copper The RDA of copper for adults is 900 mcg, based on serum copper and ceruloplasmin concentration, superoxide dismutase activity, and platelet concentration. The TUL of 10 mg/day is based on fears of liver damage, but this has never actually been observed at any copper intake in healthy people. [5] The average US intake according to NHANES II is 1700 mcg/day, well above the RDA. No groups are at significant risk of copper deficiency. [27] Although copper in vitro acts as an oxidant, studies in humans have not shown strong effects. A few studies have shown positive effects of copper on cholesterol balance and osteoporosis [28], but subsequent studies fail to confirm the result [29] and epidemiological studies on heart disease are contradictory, finding either weak positive effects or weak negative effects [30, 31]. Because of contradictory epidemiological studies and the lack of robust RCTs, there is no strong evidence for optimizing copper intake beyond simply eating a balanced diet. Fluoride The AI of fluoride for healthy adults is 3.8 mg per day for men and 3.1 for women, based on the levels found to most effectively prevent dental caries, and the TUL is 10 mg per day based on a level known not to cause skeleton fluorosis (lower levels may have adverse effects in children). The average US fluoride intake is 1.8 mg per day from food and perhaps the same amount from fluoridated water [32], for a total of about 4 mg. Fluoride is undoubtedly effective in preventing dental caries. Although most of the evidence concerns children [33], a 2007 meta-analysis found that exposure to fluoride in water or dental products decreased cavities by 27% [34]. Although there is some risk of dental fluorosis in younger children this risk disappears by about age eight; skeletal fluorosis could theoretically affect adults but has not been observed to cause any effects at normal doses [35]. Healthy adults should aim for fluoride's AI of 3.8 mg; as long as they live in a community with fluoridated water this should not require additional effort. People living in communities with nonfluoridated water may wish to consider fluoridated dental products instead of increasing dietary fluoride intake. Iodine The RDA of iodine for adults age 19-50 is 150 micrograms/day; the TUL is 1100 micrograms. The RDA was set by examining iodine turnover in the thyroid and excretion in the urine; the TUL was set by examining the intake at which thyrotropin levels rises, indicating potential subclinical hypothyroidism. The median American daily iodine intake is about 250 micrograms per day for men and 200 for women, well above the RDA, mostly due to consumption of iodized salt. [5] Ironically, the otherwise good advice to limit salt intake may be increasing the incidence of iodine deficiency, which has quadrupled over the last twenty years to 11.7% of Americans [36]. Iodine is best known for its effects on the thyroid, but as mentioned above these plateau around the RDA, and there is no evidence that more iodine improves thyroid function further. More interesting are a series of studies on iodine and breast disease. Low iodine level increases the likelihood of ductal atypia progressing to ductal carcinoma, a form of breast cancer. [37, 38]. This may explain why the Japanese, whose diet can include 10mg daily iodine or above, also have some of the world's lowest breast cancer rates. [39] . In addition, one large observational study in Finland found a strong negative correlation between iodine intake and cardiovascular disease; the results are interesting but have yet to be followed up [36]. The iodine levels found to be protective against breast disease, commonly around 6 mg [40], are well in excess of the TUL. However, the TUL was set to prevent any detectable rise in thyrotropin; most rises in thyrotropin will not be associated with clinical symptoms of hypothyroidism, and any symptoms experienced will be mild and reversible with return to a normal-iodine diet. The Japanese, who consume a seafood and seaweed-rich diet, maintain an iodine intake from 10 to as high as 45mg daily without apparent health effect [39]. Although the cardiovascular benefits are unproven, iodine's preventative potential in breast cancer seems sufficiently well grounded to support iodine supplementation in women. The evidence supports 6mg of iodine daily as a level that will minimize risk of breast cancer while being unlikely to have toxic effects despite the official TUL; anyone beginning such a program of iodine supplementation should consider contacting their doctor to discuss monitoring thyroid function. Men are at much lower risk of breast cancer and would gain few benefits from iodine supplements. Iodine supplementation can be further optimized by taking it in the form of molecular iodine; this form may be preferentially absorbed by the breast, as opposed to potassium iodine which is preferentially absorbed by the thyroid. [39]. Iron The adult RDA of iron is 8mg per day for men and 18mg for women, based on estimating losses. The TUL is 45mg per day, based on the level needed to cause gastrointestinal complaints. The average man consumes 16mg iron daily; the average woman 12. [5] Iron is most important as a component of hemoglobin; iron deficiency causes anemia, most frequently presenting as feeling "tired all the time". Groups at risk for iron-deficiency anaemia include vegetarians, pregnant women, and women who menstruate heavily; it can be diagnosed by a simple blood test. There are no advantages to taking more iron than is necessary to replace losses and prevent anemia. Individuals should try to reach their RDA of 8-18 mg iron per day. People at special risk of deficiency such as menstruating women and vegetarians should consider supplementation; any iron-containing multivitamin will work. Because iron overload can cause serious complications including cancer, heart disease and possibly neurological diseases [41], individuals should consult their doctors before beginning iron supplementation. Magnesium The RDA for magnesium is 420 mg for men and 320 for women, based on levels needed to maintain magnesium balance. The TUL is 360 mg, set to minimize risks of magnesium-induced diarrhea, but it only applies to magnesium obtained through non-food sources such as supplements. [8] The CSFII study found the average American diet to contain 323mg per day in men and 228 in women, levels which were broadly confirmed by the NHANES study. Most diets are therefore slightly magnesium deficient [27]. Magnesium has been credited with reducing hypertension, improving glycemic control, preventing cardiovascular disease; however, most comes from observational studies only, or is otherwise untrustworthy. Because magnesium is found in fruits and vegetables, observational studies that show good outcomes from high magnesium (see for example [42]) are probably only capturing the effects of a generally healthy diet. The large ARIC study found only marginal effects of serum magnesium on blood pressure, and no effect of dietary magnesium intake. [43] Some prospective studies have found magnesium to prevent heart disease [44] but others have not [45]. The latter study seems more believable, as the former found an effect in women but not men, and only when testing an overall trend rather than quartile by quartile, suggesting possible overtesting. There is some RCT support for magnesium as a treatment for diabetes [46] and migraines [47]; IV but not oral magnesium probably helps asthma [48]. Magnesium can improve cognitive functions in rats even when the rats have what appears to be a normal magnesium diet [49], but normal magnesium supplements are not neuroavailable; the study used a customized supplement of magnesium-l-threonate. This effects have never been tested in humans. Magnesium alone probably does not prevent hypertension or heart disease, but high magnesium is part of a balanced diet. Although there is not sufficient evidence to support magnesium supplementation, working towards a diet with the recommended 320-420 mg magnesium will probably improve health regardless of magnesium's particular role; such a diet would also avoid the potential gastric side effects of magnesium supplements. If an individual cannot maintain such a diet, supplementation with about 100 mg magnesium is a not entirely unreasonable strategy, albeit not one with unambiguous evidence behind it. Bioavailability studies show a slight advantage of magnesium chloride and lactate based supplements over magnesium oxide; anyone interested in testing cognitive effects should choose a neuroavailable version like magnesium-l-threonate. [50] Manganese The AI for manganese is 2.3 mg/day for men and 1.8 for women; these levels have been corroborated by balance studies. The TUL is 11 mg/day, based on a serious risk of neurotoxicity leading to Parkinsonian symptoms. [5] The average American manganese intake is 3.4 mg/day in men and 2.7 in women, well above the RDA. There are no known cases of manganese deficiency in healthy humans [51]. Like many other nutrients, manganese is part of a balanced healthy diet, and so observational studies are likely to find relationships between manganese levels and various positive health outcomes; among results most likely explicable in this way are its apparent relation to diabetes [52, 53], which did not hold up in RCTs [54]. Although some manufacturers of manganese supplements suggest the mineral has beneficial cognitive and emotional properties [55], the evidence says otherwise: high levels of manganese in water are associated with a 6.6 point IQ decrease in children [56] and increased childhood irritability [57]. Adult data is less readily available. Because of the high potential for manganese toxicity, and continuining uncertainty over possible cover toxicity of relatively low manganese levels, manganese supplementation is probably a bad idea. As usual, a balanced diet that naturally achieves the AI is the best strategy. Molybdenum The RDA of molybdenum is 45 micrograms/day, based primarily on balance studies. The TUL is 2 mg/day based on kidney failure in rats, but direct applicability to humans is unlikely [5]. Different studies have set the average daily intake at 180 micrograms [58] and around 100 micrograms [59]. There are few claims of any particular beneficial effects of molybdenum supplementation, and deficiency is rare. There is not enough evidence to recommend molybdenum optimization beyond levels available in a balanced diet. Phosphorous The RDA of phosphorus is 700mg/day, based on maintenance of safe serum phosphorus levels. The TUL is 4g per day, based on theoretical models and animal studies suggesting phosphorus can change calcium balance and calcification, but in practice no study has directly detected these effects in humans. The average intake of phosphorus is 1500 mg in males and 1024 mg in women [8]; nearly everyone exceeds the RDA primarily because of phosphorus in processed foods. Nutritionally, phosphorus is usually viewed as a potential danger, as exemplified by warnings about phosphoric acid in soda. However, studies have failed to confirm this danger. Despite worries about calcium:phosphorus ratios, even extremely low Ca:P ratios failed to produce detectable effects [60]. Some animal experiments showed skeletal lesions in rabbits on a very-high-phosphorus diet, but these required around forty times the phosphorus levels even the most prolific soda-drinker could expect [61]. Likewise, metastatic calcification (which despite its name is not a cancerous process but only the abnormal deposition of calcium in tissue) does indeed seem linked to high serum phosphorus, but at levels only attainable by disease processes; even dietary phosphorus intakes above the 95th percentile have never been observed to favor such a process [8]. Although "phosphoric acid" sounds sinister, the amount of phosphorus in soda is relatively small, and although some observational studies do show negative effects of soda on bone health, this could equally likely represent soda replacing healthier calcium-rich beverages like milk, or a general correlation between excessive soda use and an unhealthy diet [62]. Drinking large quantities of soda is probably unhealthy for very many reasons, but excess phosphorus is probably not one of them. Healthy individuals probably have no reason to try to optimize their phosphorus intake beyond eating a well-balanced diet. Potassium The AI of potassium for adults age 19-50 is 4.7g, which was set at the level found to most effectively decrease blood pressure and risk of kidney stones. The kidneys regulate potassium balance tightly enough to prevent overload in healthy people, and so there is no TUL. [63] There is a robust evidence base for the efficacy of potassium in reducing blood pressure. A Cochrane meta-analysis of six RCTs found a statistically nonsignificant decrease in systolic blood pressure of 3.9 mm Hg, and in diastolic blood pressure of 1.5 mm Hg upon potassium suppelementation, although results were inconsistent and the authors suggest cautious interpretation of the results [64]. There was no advantage in supplementation of >4g over supplementation of less than that amount. A different meta-analysis of 33 studies found that potassium supplements of between 2.3 and 3.9g per day decreased blood pressure by a statistically significant level of 1.8/1 in normotensive and 4.4/2.5 in hypertensive subjects. [65]. A meta-analysis by the College of Cardiology containing a total of 247510 subjects found that subjects with a high-potassium diet, on average 1.64g higher than those with low-potassium diets, had a 21% lower risk of stroke, although this was an observational study and may show nothing more than that people who eat more fruits and vegetables, and therefore more potassium, are more healthy in general [66] All these studies broadly agree with the DRI's AI, a 4.7g figure which would require an extra 2.5g per day over normal dietary intake. Therefore, potassium supplementation is advised for both men and women. Unfortunately, potassium supplements are not widely available; the FDA bans supplements with more than 55mg potassium because of their potential danger to renal patients [63]. Alternative methods of increasing dietary potassium include a balanced diet with more fruits and vegetables (most famously bananas) or liberal use of potassium-based salt (which has the added advantage of cutting down on unhealthy sodium-based salts). People on long-term medications or with renal disease should talk to their doctor before trying to increase the potassium in their diet. Selenium The RDA of selenium for both men and women is 55 micrograms per day, a number set by examining the activity plateau of the selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase enzyme. The TUL is 400 micrograms per day, set upon derivation of likely selenium intake for five patients with selenium poisoning leading to hair and nail loss. [5] Different studies have found the average American diet to contain 81 [67] to 87 [68] micrograms selenium per day. No overt symptoms of selenium deficiency or excess have ever been observed in healthy American adults. Selenium is a cofactor for the reduction of antioxidant enzymes. Many claims have been made that antioxidants help fight cancer, heart disease, and even normal aging, but the most complete investigation of these claims, a Cochrane meta-analysis of 67 studies and over 200,000 individuals, contradicts these claims and found no significant effect of antioxidant supplementation on mortality [69]. Somewhat more plausible are claims that selenium helps prevent cancer. Selenium supplementation consistently lowers cancer risk in small animal models [70]. Low selenium and cancer have also been correlated in several observational studies on humans, but this may be an effect of class; wealthy people have higher selenium intakes and are less likely to develop cancer. However, some RCTs have also found an effect; the NPCT found a significant 37% decrease in cancer incidence and 50% decrease in cancer mortality over 1312 subjects after supplementation with 200 micrograms selenium. [71] However, further studies have failed to confirm this finding. The SELECT study of 35,534 men analyzed prostate cancer, one of the cancers most affected in NPCT, but found no statistically significant effect from the same 200 microgram dose. [72]. A Cochrane review of six RCTs concluded that “the trials with the most reliable results found that organic selenium did not prevent prostate cancer in men and increased the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer in women and men. Other trials found that participants using selenium salt or organic supplements had a decrease in liver cancer cases. However, due to methodological shortcomings this evidence was less convincing.” Although there are many studies on both sides, most experimental studies, especially the largest, find no benefit of selenium supplementation in prevention of prostate cancer or any other type of cancer; some find increases in non-melanoma skin cancer, in prostate cancer [72], or a dose-dependent relationship in which all cancers increase at selenium intakes greater than 150 micrograms per day [73]. Therefore, selenium supplementation cannot be recommended at the present time [74]. This is especially true of supplementation in the form of selenium-containing multivitamins, which are advertised as preventing prostate cancer but actually increase risk of prostate cancer slightly. [6]. Individuals should continue to aim for the RDA of 55 micrograms per day selenium unless they have specific medical reasons for doing otherwise. Sodium The AI for sodium is 1.5g/day, but the DRI admits that people can survive and thrive on sodium intakes less than .2g per day, and that the higher recommendation is only to “ensure that the overall diet provides an adequate intake of other important nutrients and to cover sodium sweat losses in unacclimatized individuals." The TUL is 2.3g, selected primarily because it "was ... the next level above the AI that was tested" but the detrimental effects of sodium seem gradual and mostly linear, making a true cutoff difficult. [63] The average American diet includes 3.1-4.7g sodium for men and 2.3 to 3.1g for women from food, but this does not include table salt and so probably underestimates the real amount. [27]. The INTERSALT study [75] confirmed the now universally accepted idea that sodium intake is linked to high blood pressure, a risk factor for heart attack and stroke. The DASH-Sodium study found that restricting sodium to 1500 mg sodium/day diet decreased blood pressure by 5.6/2.8 mm Hg [76]. The literature on sodium and hypertension supports a recommendation to limit sodium as far as possible. The strongest evidence base supports positive effects of sodium limitation at least down to 1500 mg/day; limiting it further may reduce blood pressure even more but is probably not practical in a modern diet. Zinc The RDA of zinc is 11mg/day for men and 8mg/day for women, based on zinc balance studies and the activity of the the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase enzyme. The TUL is 40 mg/day, again based on the best range for enzyme activity. The average American diet includes 14mg/day zinc in men and 9mg/day in women, slightly above the RDA; 16 percent also supplement this with zinc-containing vitamins. [4] Zinc deficiency is relatively rare among healthy adults in developed countries, although it is sometimes suffered by vegetarians, who consumed high levels of bioavailability-decreasing phytic acid [77] Although zinc is well-known for purported benefits against disease processes from the common cold to HIV/AIDS, there are relatively few and modest claims of benefits in healthy people. One study suggested a role against macular degeneration [78], but it was poorly conducted, ran too many tests, and only achieved a marginally significant result [79]; subsequent studies have found no effect [80]. There is little evidence for zinc supplementation in healthy people. Vegetarians who expect their diet to be deficient in zinc may wish to supplement; there are few reasons to prefer any form of zinc supplement over another [4]. Other nonessential minerals Lithium is not often considered an essential mineral, but deficiency studies show effects ranging from low litter size in rats to behavioral abnormalities in humans [LITHIUM_1]. There is no federally established RDA or TUL for lithium; an unofficial TUL is 100 mg. The average intake is around 650 micrograms. The doses of lithium used medically to eg treat bipolar disorder, usually 100 mg/day or above, are potentially highly toxic and must be monitored by medical professionals to prevent heart, kidney, and other forms of damage. However, much smaller doses of lithium are found in drinking water, and seem to have several positive effects. An observational study in Japan found high lithium levels in drinking water (with tested levels ranging from .7 to 59 micrograms/liter) to significantly decrease all cause mortality (p = .003); a followup experiment with nematodes found lithium supplementation could increase nematode lifespan by 4-36% [81,82]. Even more interesting is a study from Texas municipalities with lithium levels in drinking water ranging from negligable to 170 micrograms/liter; individuals in high-lithium cities side had fewer crimes, suicides, and drug addictions (p < .01). [83] These water levels would correspond to about 340 micrograms/day extra lithium. In the laboratory, positive effects have been found with lithium supplementation of as little as 400 micrograms [84]. It seems plausible that supplementation of around 1 mg lithium per day could have significant positive benefits, while not reaching the levels necessary for toxicity. Certainly this level would be recommended for people with subclinical mood problems or psychiatric problems. Lithium citrate or carbonate of the sort used in bipolar disorder is not available over the counter, but lithium orotate supplements are. Taking doses of lithium larger than the upper end of the natural distribution, even as low as 5 mg, could be dangerous and should be discussed with a doctor. Analysis The statistical value of a year of human life is commonly set around $100,000; supplementation of some dietary minerals may save lives. This possibility must be weighed against the costs of taking that supplement, both financial and in terms of annoyance. Many supplements cost around the range of $25/year; they may take a few hours to obtain, taste unpleasant, and cause some minor side effects like stomach upset: we will arbitrarily decide these additional costs are worth about another $25. An average individual may take the supplement for about fifty years, from the time they become an adult to old age. In this model, the lifetime cost of the supplement is $2500, and the individual should take the supplement if they believe there to be greater than a 1/40 chance it will save at least a year of life. Most potentially preventable diseases occur around the end of life. Taking cancer and heart disease as two prototypical examples, the average age for a first heart attack is 68 [85] and the average age of a cancer diagnosis is 67 [86]. The average US life expectancy is 78 years [87]. The "natural" conclusion that preventing one episode of cancer or heart disease therefore potentially saves ten years is probably an overestimate; people who get cancer or heart disease are probably in general less healthy, and not every episode prevented will be the first episode; suppose then that preventing one episode of serious disease potentially saves five years. The death rate from heart attack is 38%; the five-year death rate from all cancers averaged 50% [88]. So although preventing one episode of serious disease potentially saves five years, it actually saves only half of that, because half the patients would survive. If a year is worth $100,000, successful supplementation saves 2.5 years, and supplementation costs $2,500, this suggests that a supplement is valuable if it has a 1/100 chance of successfully preventing one episode of serious disease if taken over a lifetime. This number is inadequate for many reasons: it excludes the benefits of preventing nonfatal illnesses, it excludes the possibility that a supplement may have side effects and so have negative value, and, of course, it is only an extremely rough estimate. Taken as a rough estimate, however, it provides a bar for these mineral supplements to pass: they should have a 1% chance of preventing a serious disease, or be equally valuable in some other way. Several supplements reach this bar. As mentioned above, potassium supplementation decreases systolic blood pressure by 2-4 points. Although the exact point-by-point relationship between hypertension and cardiovascular disease depends on several factors, most people could decrease heart disease risk by 50% with a 10 point drop in blood pressure [89], suggesting that potassium's 2-4 point drop well exceeds the 1% threshold even before other hypertensive diseases such as stroke are factored in. Low sodium diets, which have even greater effects on blood pressure, similarly pass this bar. Although iodine probably has a protective effect against breast cancer, it is hard to quantify exactly what it is. The number 50% comes up often: first as 50% decrease in breast pain from a precursor condition to breast cancer [90] and second as the amount breast cancer declined in an unpublished study that seems somewhat questionable [39]. More likely the number is much lower, but even at a tenth of this level it would still pass the 1% threshold. Lithium is the most poorly-researched and most uncertain of all the minerals in this analysis. It improved lifespan 4-36% in nematodes, but is unlikely to be anywhere near as effective in humans. Further, much of its effect would probably be on mood and psychological well-being, which would operate independently of concerns about lifespan. Nevertheless, its low cost (under $20/year) makes it a reasonable option. Other dietary minerals do not seem to have any quantifiable benefits at levels beyond those in a normal diet. Works Cited [1] Nelson, David L.; Michael M. Cox. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, Third Edition (3 Har/Com ed.). W. H. Freeman. [2] "Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) Resources ". Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, United States National Academies. 2004. Retrieved 2011-12-31 [3] Linus Pauling Institute (2011). Micronutrient Information Center. Retrieved from http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/ [4] "Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc". Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, United States National Academies. 2001. Retrieved 2011-12-31. [5] "Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids". Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, United States National Academies. 2001. Retrieved 2011-12-31. [6] Neuhouser ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Thomson C et al. (2009). "Multivitamin use and risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease in the Women's Health Initiative cohorts". Arch Intern Med 169 (3): 294–304. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.540. PMID 19204221. [7] Huang HY, Caballero B, Chang S, Alberg A, Semba R, Schneyer C, Wilson RF, Cheng TY, Prokopowicz G, et al. Multivitamin/mineral supplements and prevention of chronic disease. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. No. 139. (Prepared by The Johns Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0018). AHRQ Publication No. 06-E012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. May 2006. [8] "Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride". Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, United States National Academies. 2001. Retrieved 201112-31. [9] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 23, 2010. [10] Bjelakovic G, Gluud C. Vitamin and Mineral Supplement Use in Relation to All-Cause Mortality in the Iowa Women's Health Study - Comment on "Dietary Supplements and Mortality Rate in Older Women" . Arch Intern Med Oct 11 2011 [11] Rosen, HN. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation in osteoporosis. In: UpToDate, Basow, DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2012. [12] Baron JA, Beach M, Mandel JS, et al. Calcium supplements for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. Calcium Polyp Prevention Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine 1999; 340(2):101–107. [13] Wu K, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Giovannucci EL. Calcium intake and risk of colon cancer in women and men. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2002; 94(6):437–446. [14] Dietary intake of dairy products, calcium, and vitamin D and the risk of hypertension in middle- aged and older women. Wang L, Manson JE, Buring JE, Lee IM, Sesso HD. Hypertension. 2008 Apr;51(4):1073-9. Epub 2008 Feb 7 [15]: Dickinson HO, Nicolson DJ, Cook JV, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Ford GA, Mason J. Calcium supplementation for the management of primary hypertension in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006: CD004639. [16] Bolland MJ et al. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d2040. [17] Wang L, Manson JE, Song Y, Sesso HD. Systematic review: vitamin D and calcium supplementation in prevention of cardiovascular events. Ann Intern Med2010;152:315-23. [18]: Skinner HG and Schwartz GG (2008) Serum calcium and incident and fatal prostate cancer in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17: 2302–2305 [19]: Gao X, LaValley MP, Tucker KL. Prospective studies of dairy product and calcium intakes and prostate cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:1768–77. [20] Anderson RA, Polansky MM, Bryden NA, Canary JJ. 1991. Supplemental-chromium effects on glucose, insulin, glucagon, and urinary chromium losses in subjects consuming low-chromium deits. Am J Clin Nutr 54:909-916 [21] Kim WW, Mertz W, Judd JT, Marshall MW, Kelsay JL, Prather ES, 1984. Effect of making duplicate food collections on nutrient intakes calculated from diet records. Am J Clin Nutr 40:13331337. [22] Pittler MH, Stevinson C, Ernst E. Chromium picolinate for reducing body weight: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 Apr;27(4):522-9. [23] Vincent JB. The potential value and toxicity of chromium picolinate as a nutritional supplement, weight loss agent and muscle development agent. Sports Medicine. 33.3 (2003): 213-230. [24] Linus Pauling Institute (2011). Micronutrient Information Center: Chromium. Retrieved from http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/minerals/chromium/ [25] Martin J, Wang ZQ, Zhang XH, et al. Chromium picolinate supplementation attenuates body weight gain and increases insulin sensitivity in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(8):1826-1832. [26] Effect of chromium supplementation on glucose metabolism and lipids: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Balk EM, Tatsioni A, Lichtenstein AH, Lau J, Pittas AG Diabetes Care. 2007;30(8):2154. [27] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [28] Klevay LM. Lack of a recommended dietary allowance for copper may be hazardous to your health. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998 Aug;17(4):322-6. [29] Turley E, McKeown A, Bonham MP, et al. Copper supplementation in humans does not affect the susceptibility of low density lipoprotein to in vitro induced oxidation (FOODCUE project). Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29(11):1129-1134. [30] Klevay LM. Cardiovascular disease from copper deficiency--a history. J Nutr. 2000;130(2S Suppl):489S-492S. [31] Ford ES. Serum copper concentration and coronary heart disease among US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(12):1182-1188. [32] Taves DR. 1983. Dietary intake of fluoride ashed (total fluoride) vs. unashed (inorganic fluoride) analysis of individual foods. Br J Nutr 39:295-301 [33] McDonagh M, Whiting P, Bradley M et al. A systematic review of public water fluoridation; 2000. Report website: NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [34] S.O. Griffin, E. Regnier, P.M. Griffins, and V. Huntley. Effectiveness of Fluoride in Preventing Caries in Adults. Journal of Dental Research May 2007 vol. 86 no. 5 410-415 doi: 10.1177/154405910708600504 [35] Fawell J, Bailey K, Chilton J, Dahi E, Fewtrell L, Magara Y. Fluoride in Drinking-water [PDF]. World Health Organization; 2006. ISBN 92-4-156319-2. Guidelines and standards. p. 37–9. [36] Cann SAH. Hypothesis: dietary iodine intake in the etiology of cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Nutr 2006;25(1):1-11. [37] Ghent WR, Eskin BA, Low DA, Hill LP. Iodine replacement in fibrocystic disease of the breast. Can J Surg. Oct 1993; 36:453-460. [38] Kessler JH. The effect of supraphysiologic levels of iodine on patients with cyclic mastalgia. Breast J. 2004;10(4):328-336. [39]:Ware, W. (2006). Primary Prevention of Breast Cancer. Retrieved from http://www.yourhealthbase.com/breast_cancer_prevention.htm [40] Kessler J, The Effect of Supraphysiologic Levels of Iodine in Patients with Cyclic Mastalgia, The Breast Journal 2004. [41] Linus Pauling Institute (2011). Micronutrient Information Center: Iron. Retrieved from http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/minerals/iron/ [42] Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Bray GA, Vogt TM, Cutler JA, Windhauser MM, Lin PH, Karanja N. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1117-24. [43] Peacock JM, Folsom AR, Arnett DK, Eckfeldt JH, Szklo M. Relationship of serum and dietary magnesium to incident hypertension: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9(3):159-165. [44] Liao F, Folsom AR, Brancati FL. Is low magnesium concentration a risk factor for coronary heart disease? The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J. 1998;136(3):480-490. (PubMed) [45]: Song Y, Manson JE, Cook NR, Albert CM, Buring JE, Liu S. Dietary magnesium intake and risk of cardiovascular disease among women. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(8):1135-1141. (PubMed) [46] Song Y, He K, Levitan EB, Manson JE, Liu S. Effects of oral magnesium supplementation on glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized double-blind controlled trials. Diabet Med. 2006;23(10):1050-1056. (PubMed) [47] Mauskop A, Altura BM. Role of magnesium in the pathogenesis and treatment of migraines. Clin Neurosci. 1998;5(1):24-27 [48] Rowe BH, Bretzlaff JA, Bourdon C, Bota GW, Camargo CA, Jr. Magnesium sulfate for treating exacerbations of acute asthma in the emergency department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001490 [49] Slutsky I, Abumaria N, Wu LJ, Huang C, Zhang L, Li B, Zhao X, Govindarajan A, Zhao MG, Zhuo M, Tonegawa S and Liu G. Enhancement of Learning and Memory by Elevating Brain Magnesium. Neuron, Jan. 28, 2010 [50] Firoz M and Graber M. Bioavailaility of US commercial magnesium preparation. Magnes Res 2001;14:257-62. [51] Manganese Supplement (2012). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/drug-information/DR602287 [52] el-Yazigi A, Hannan N, Raines DA. Urinary excretion of chromium, copper, and manganese in diabetes mellitus and associated disorders. Diabetes Res. 1991;18(3):129-134. [53] Ekin S, Mert N, Gunduz H, Meral I. Serum sialic acid levels and selected mineral status in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol Trac Elem Res. 2003;94:193-201. [54] Walter RM, Aoki TT, Keen CL. Acute oral manganese does not consistently affect glucose tolerance in non diabetic and type II diabetic humans. J Trace Elem Exp Med. 1991;4:73-79. [55]: "Ultimate Fat Burner" (2011). Manganese Benefits and Side Effects. Retrieved from http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/ [56]: Bouchard MF, Sauvé S, Barbeau B, Legrand M, Brodeur MÈ, Bouffard T, Limoges E, Bellinger DC, Mergler D. Intellectual impairment in school-age children exposed to manganese from drinking water. Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Jan;119(1):138-43. Epub 2010 Sep 7. [57]: Khan K, Wasserman GA, Liu X, Ahmed E, Parvez F, Slavkovich V, Levy D, Mey J, van Geen A, Graziano JH, Factor-Litvak P. Manganese exposure from drinking water and children's academic achievement. Neurotoxicology. 2011 Dec 13;33(1):91-97. [58] Tsongas TA, Meglen RR, Walravens PA, Chappell WR. 1980. Molybdenum in the diet: An estimate of average daily intake in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 33:1103-1107. [59] Pennington JAT, Jones JW. 1987. Molybdenum, nickel, cobalt, vanadium, and strontium in total diets. J Am Diet Assoc 87:1644-1650. [60] Heaney RP, Recker RR. 1982. Effects of nitrogen, phosphorus, and caffeine on calcium balance in women. J Lab Clin Med 99:46-55. [61] Krook L, Whalen JP, Lesser GV, Berens DL. 1975. Experimental studies on osteoporosis. Methods Achiev Exp Pathol 7:72-108. [62] Fitzpatrick L, Heaney RP. Got Soda? J of Bone and Mineral Research. 2003;18(9):1570-1572 [63] "Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate". Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, United States National Academies. 2001. Retrieved 2011-12-31. [64] Dickinson HO, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Mason J. Potassium supplementation for the management of primary hypertension in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004641. [65] Whelton PK, He J, Cutler JA, et al. Effects of oral potassium on blood pressure. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. JAMA. 1997;277(20):1624-1632. [66] Lanfranco D, et al. Potassium Intake, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Disease A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J Am Col of Cardio 2011; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.070 [67] Welsh SO, Holden JM, Wolf WR, Levander OA. 1981. Selenium in self-selected diets of Maryland residents. J Am Diet Assoc 79:277-285. [68] Pennington JA, Schoen SA. 1996. Total diet study: Estimated dietary intakes of nutritional elements, 1982-1991. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 66:350-362. [69] Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007;297:842-57. [70] Whanger. Selenium and its relationship to cancer: an update. Br J Nutr 91:11-28 (2004). [71] NPCT: Clark LC, Combs GF Jr, Turnbull BW, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:1957 [72] EA Klein, IM Thompson, CM Tangen, et al. Vitamin E and the Risk of Prostate Cancer: Results of The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 2011; 306(14) 1549-1556. [73] Bleys J, Navas-Acien A, Guallar E. Serum selenium levels and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality among US adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):404 [74] Dennert G, Zwahlen M, Brinkmann M, Vinceti M, Zeegers MPA, Horneber MA. Selenium for preventing cancer. 2010. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. [75] Elliott P, Stamler J, Nichols R, et al. Intersalt revisited: further analyses of 24 hour sodium excretion and blood pressure within and across populations. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. BMJ. 1996;312(7041):1249-1253. [76]: Karanja, Njeri; Erlinger, TP; Pao-Hwa, Lin; Miller 3rd, Edgar R; Bray, George (September 2004). "The DASH Diet for High Blood Pressure: From Clinical Trial to Dinner Table". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (Lyndhurst, Ohio: The Cleveland Clinic Foundation) 71 (9): 745-53. doi:10.3949/ccjm.71.9.745. ISSN 0891-1150. PMID 15478706. Retrieved 2011-12-28. [77] Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Zinc. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001:442-501. (National Academy Press) [78]: Newsome DA, Swartz M, Leone NC, Elston RC, Miller E. Oral zinc in macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(2):192-198. [79]: AREDS Investigators Distort Findings. Seigel et al. Arch Ophthalmol.2002; 120: 100-101. [80]: Stur M, Tittl M, Reitner A, Meisinger V. Oral zinc and the second eye in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(7):1225-1235 [81]: Schrauzer GN. Lithium: occurrence, dietary intakes, nutritional essentiality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002 Feb;21(1):14-21. [82] Kim Zarse, Takeshi Terao, Jing Tian, Noboru Iwata, Nobuyoshi Ishii, Michael Ristow. Low-dose lithium uptake promotes longevity in humans and metazoans. European Journal of Nutrition, 2011 [83]: Dawson EB: The relationship of tap water and physiological levels of lithium to mental hospital admission and homicide in Texas. In Schrauzer GN, KlippelKF (eds): “ Lithium in Biology and Medicine.” Weinheim: VCH Verlag, pp 171–187, 1991. [84]: Schrauzer GN, de Vroey E. Effects of nutritional lithium supplementation on mood: A placebocontrolled study with former drug users. Biol Trace Elem Res 40(1):89-101, 1994 [85] Roger V, Go, A, Lloyd-Jones, D, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update. a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics SubcommitteeExternal Web Site Icon. Circulation 2011;123:e1-e192. [86] Median Age of Cancer Patients at Diagnosis, 2000-2003. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 19752003. National Cancer Society. Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2003/results_single/sect_01_table.11_2pgs.pdf [87] CIA - The World Factbook 2008 – Rank Order - Life expectancy at birth. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2102.html [88] Heart Attack Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.allheartattack.com/statistics.php [89] Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.Hypertension. 2003 Dec;42(6):1206-52. Epub 2003 Dec 1. [90] Linus Pauling Institute (2011). Micronutrient Information Center: Iodine. Retrieved from http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/minerals/iodine/