Body mass index, hepatic fibrosis and inflammation in chronic

advertisement

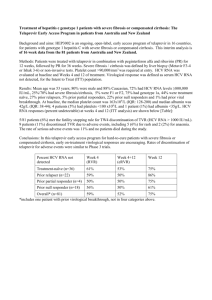

Body mass index, hepatic fibrosis and inflammation in chronic hepatitis C: a retrospective study El- Badawy RM. MD, Abdo S.A MD, Glalal Mawad MD, Magdy A. Gad, Entesar H. El-Sharqawy MD, Amin H. MD, Aza A. Senna MD, Dept. pf heptology, gastroenterology and Clinical pathology Department Benha Faculty of Medicine – Zagazig University Abstract: The factors that contribute to histological progression of liver disease in HCV are still under investigation. The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of "Body Mass Index" (BMI) as a measure of obesity on the outcome of chronic HCV infection. The present study retrospectively included 30 consecutive patients from the department of hepatology, gastroenterology and infectious disease at Benha university hospitals between June 2003 and April 2004. Patients included 24 ♂ and 6 ♀ with age range from 25-70 years and BMI between 20-36 kg/m2. The patients were grouped into 2 groups not obese and obese (13/30 and 17/30) respectively. Three factors were identified as independently influencing prognosis: age, BMI and serum ALT. The relative risk of developing advanced fibrosis in obese group is 13 folds the non-obese patients. In conclusion despite the limitations of cross sectional studies, the relative risk of fibrosis progression related to BMI in our analysis as well as in the literature is probably indisputable. However, further longitudinal cohort studies are needed to confirm the current consensus. Introduction: The majority of cases of primary hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection result in persistent viraemia. Progression to cirrhosis marks the onset of risk for complications such as liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma. However, while liver disease progression appears more indolent than previously reported, it is highly variable (2). Identifying factors that influence outcome is important in order to counsel individuals regarding prognosis and facilitate decisions related to clinical management. A number of factors have been proposed as promoting HCV-related liver fibrosis. These include: host ethnicity, gender, obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking, age at infection, mode of HCV acquisition, serum transaminase levels, histological grade of inflammation, co-infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or HIV, HCV genotype, viral load and quasi species diversity (1). The aim of the present study is to evaluate the impact of "Body Mass Index" (BMI) as a measure of obesity on the outcome f chronic hepatitis C virus infection and to compare this impact with that of other pertinent historical, biochemical and virological parameters. Patients and methods Patient selection: The present study retrospectively included 30 consecutive patients from the Department of hepatology gastroenterology and infectious diseases at Benha University hospitals between June 2003 and April 2004. Patients were included in the study if: (1) positive for HCV RNA reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR); (2) a liver biopsy is available; (3) had no history of alcohol use; (4) negative serology for hepatitis B surface antigen; (5) absence of other causes of prior anti-HCV treatment; and (6) no history of hepatic decompensation defined as the presence of ascites, jaundice (total bilirubin > 3 mg/dL), variceal bleeding, or hepatic encephalopathy (3). Methods and data collection: Data collected included age, gender, risk factors for acquiring HCV infection (specifically: blood transfusion, dental treatment, previous surgical operations) and BMI. Patients with a BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 were categorized as overweight, and patients with a BMI >30 kg/m2 were categorized as obese (9). Quantitative HCV RNA PCR was performed in all patients, and HCV genotyping was carried out (22). Routine laboratory data included complete blood counts, albumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and prothrombin time (PT). All patients underwent abdominal ultrasonography to rule out hepatocellular carcinoma. In all patients, ultrasonography was used to measure spleen size; a maximal spleen dimension of more than 13 cm indicated splenomegaly. Hepatic histology Hematoxylin-eosin and trichrome stainings were used for histology assessment. Knodell's scoring system was used to stage hepatic fibrosis (16). While stage 0 represented the absence of hepatic fibrosis, stage III/IV represented advanced hepatic fibrosis. HAI (i.e. total Knodell score-fibrotic score) was used to grade activity of CHC (16). In the present study, an HAI of more than 7 was considered active liver injury (5, 12 & 19) . Statistical analysis The descriptive data were presented as percentage or mean with standard deviation or range. Either Chi-square test, Fisher's Exact Test. Student's t-test, or analysis of variance test was used to compare frequencies or means, respectively. Both univariate test was used to compare frequencies or means, respectively. Both univariate and multivariate analysis were used and the odds ratios were calculated by using Logistic regression model. Multiple univariate analysis were carried out to determine the risk factors for and association of CHC activity with BMI. A P value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Results Baseline demographic findings The baseline demographic data are summarized in Table 1. Of the 30 patients with recorded BMI, the mean BMI was 28.4 ± 4.9 (20-36) kg/m2. Obesity was seen in 17/30 (56.7%) patients. Overall, 23/30 (76.7%) patients were overweight or obese. Histologically, 10 (33.3%) had stages III or IV fibrosis, while 20 (66.7%) had stages I and II fibrosis. In the present study, patients with stages III and IV fibrosis were combined as a group with advanced firbrosis; and patients with stages I and II were combined as a group with mild fibrosis. Of the 30 patients with recorded HAI, the median grade was 2. Seven (23.3%) had HAI grade I; 14 (46.7%) had HAI grade II; 7 (23.3%) grade III and 2 (6.7%) had grade IV. Table (1): Features of 30 enrolled patients 46.6 ± 8.2 (25-58) 24:6 28.8 ± 4.9 (20-36) 17 (56.7%) 23 (76.7%) 1.15±0.4mg/dL (0.7-2.1) 4.1±0.4g/dL (3.2-5.0) 98.9±54.1 IU/L (45-271) 70.2±27.9 IU/L (30-130) 12.9±0.8s (11-15) 11 (36.7%) 9 (30.0%) 5 (16.7%) 5 (16.7%) Age, yr (mean ± SD) (Range) Sex (M:F) BMI (mean ± SD) (Range) Obesity (BMI>30)% Overweight (BMI>25) (%) Bilirubin (mean ± SD) (Range) Albumin (mean ± SD) (Range) ALT (mean ± SD) (Range) AST (mean ± SD) (Range) PT (mean ± SD) (Range) Fibrosis 1 2 3 4 Necro-inflammation 1 2 3 4 Genotype Type 1 Type 4 Viral Load (mean ± SD) (Range) 7 (23.3%) 14 (46.7%) 7 (23.3%) 2 (6.7%) 1 (3.3%) 29 (96.7%) 751710.1±1155749.1 (1000-4401000) Table (2): Comparison between the MILD and ADVANCED fibrosis groups. AGE HB WBCS PLATELET BILIRUBIN ALBUMIN PT ALT AST PCR BMI FIBROSIS N Mean SD Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced Mild Advanced 20 10 20 10 20 10 20 10 20 10 20 10 20 10 20 10 20 10 20 10 20 10 38.85 50.30 14.02 14.25 7175.00 6810.00 240450 200100 1.06 1.34 4.22 3.92 12.66 13.27 83.20 130.40 63.65 83.20 764669.00 725792.30 27.05 32.40 8.67 4.62 1.16 1.87 2351.46 2786.26 65630 39515 0.41 0.33 0.44 0.41 0.76 0.82 53.45 41-88 25.79 28.66 1296386.82 868913.18 4.807 2.413 P Value 0.001 0.681 0.709 0.086 0.066 0.089 0.052 0.021 0.070 0.933 0.003 Patients with advanced fibrosis had higher age mean, ALT and BMI (Table 2). Table (3): Logistic univariate regression analysis of all variables for the prediction of advanced fibrosis AGE BMI ALT PT BILIRUBIN AST PLATELET ALBUMIN HB WBCS PCR OR (95% CI) P Value 1.43 (1.06-1.47) 1.44 (1.07-1.94) 1.02 (1.00-1.04) 2.78 (0.93-8.31) 6.37 (0.82-49.74) 1.03 (0.99-1.06) 1.00 (0.99-1.001) 0.19 (0.02-1.38) 1.13 (0.65-1.97) 0.99 (0.98-1.00) 1.00 (0.99-1.001) 0.007 0.016 0.046 0.067 0.077 0.082 0.094 0.099 0.669 0.698 0.929 Table (3) summarizes results of univariate regression analysis of eleven clinical virological, and biochemical parameters as possible risk factors for advanced hepatic fibrosis. It revealed that being overweight/obese (i.e. BMI >25 kg/m2) with elevated ALT eventually constitutes with the advancement in age a statistically significant risk factor for the development of grades III/IV hepatic fibrosis. Unvariate analysis (Table 3) did not reveal association of the level of viral load with hepatic fibrosis. In this study, the number of cases with genotype other than 4 was not statistically adequate to draw any conclusions as regards the role of genotyping in the development of irreversible stages of chronic liver disease. Table (4) showing the distribution of cases with advanced (Stages III/IV) fibrosis among obese and non-obese patients. It is clear that the difference is statistically significant. Moreover, from the same table it is possible to calculate the relative risk of developing advanced fibrosis in an obese patient with HCV as 2.25 (95% CI of 1.27-3.99). In contrast, the relative risk in a non-obese patient is only 0.17 (95% CI of 0.008-0.704) (P < 0.05). Table (4): Comparison between obese and non-obese patients as regards the stage of hepatic fibrosis: Mild Fibrosis Advanced Fibrosis Total (%) Not Obese Obese Total (%) P Value 12 1 13 (43.3%) 8 9 17 (56.7%) 20 (66.7%) 10 (33.3%) 0.0268 Table (5): Comparison between obese and non-obese patients the grade of hepatic necro-inflammation (HAI): Mild Severe Total (%) Not Obese Obese Total (%) P Value 12 1 13 (43.3%) 9 8 17 (56.7%) 21 (70%) 9 (30%) 0.0417 Furthermore, obesity was also significantly associated with a higher HAI (Table 5), a histological indicator of active CHC (14). These data indicate that in patients with CHC, a higher BMI is more associated with an active and progressive CHC. Discussion: This study examined factors associated with progression to cirrhosis in people with chronic HCV infection. Following statistical analysis of factors associated with disease progression, three were identified as independently influencing prognosis: age, BMI, and serum ALT level (Table 2 and 3). Age of the patient at the time of infection has consistently been associated with more rapid progression to cirrhosis in patients with chronic HCV infection. A number of studies have demonstrated that subjects infected at an older age develop cirrhosis over a shorter period (6). In a high endemicity area like Egypt, a major proportion of the population at risk are exposed to infection early in their life. Therefore, more advanced liver disease is significantly more prevalent among older age groups (Table 2 and 3). Children with chronic HCV infection have been shown to have disproportionably low rates of fibrosis progression (11). Serum transaminase levels fluctuate significantly in patients with chronic HCV infection and poorly predict the extent of liver damage (17). However, recent studies have demonstrated slower disease progression rates for chronic HCVinfected patients with persistently normal ALT levels compared to patients with elevated ALT levels (10). The results of the present study support an independent association between elevated serum ALT levels and increased risk of progression to cirrhosis (Table 2 and 3). It is unclear whether viral factors, such as virulence of the infecting viral genotype, viral load and quasi species diversity, impact on the development of HCV-related cirrhosis, Infection with HCV genotype I, particularly subtype 1b- has been reported to increase the rate of progression to HCV- related cirrhosis (22) . Rather than a direct effect attributable to HCV genotype, it may be that genotype prevalence is changing, other genotypes are becoming more common and patients with genotype 1b have simply been infected for longer. Studies that have considered other factors related to disease progression have typically failed to find any association between HCV genotype and cirrhosis (10). The analysis reported here was unable to examine the impact of viral genotype on HCV-related liver disease progression because only one patient had genotype 1. Progression to cirrhosis has also been associated with higher serum viral load in some studies (4). In the analysis reported here, viral load showed no identifiable impact on disease progression. This is in agreement with recent evidence suggesting that viral load does not influence disease progression in chronic HCV infection (18). In the present study, BMI proved to be an independent risk factor for the development of hepatic fibrosis (Tables 2, 3 and 4). The relative risk of developing advanced fibrosis in an obese patient with HCV is 13 folds the relative risk in non-obese patient. The mechanism by which obesity contributes to HCV progression is unclear. Several pathogenetic mechanisms might be involved, including steatosis, steatohepatitis, leptin, insulin resistence and genetic factors. Steatosis is a common histological finding occurring in more than 50% of patients with chronic hepatite C. In patients with viral genotype 3, steatosis may be a cytopathic effect of the virus (7). In at least a proportion of patients with HCV the pathogenesis of steatosis appears to be the same as for patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, i.e., related to visceral adiposity and elevated to visceral adiposity and elevated circulating insulin levels. A highly significant relationship between steatosis and body mass index (BMI) in patients with untreated chronic HCV was established in previous studies (12 & 19) . These studies also revealed a significant relationship between steatosis and hepatic fibrosis, suggesting that in chronic HCV, steatosis plays a role in disease progression. In support of this Hichman(7) showed that weight loss is associated with an improvement in liver histology and biochemistry in patients with chronic HCV (14). In conditions such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and alcoholic liver disease, steatosis is associated with the development of acinar inflammation (7) . In this work, obesity was also found to be significantly associated with hepatic necro-inflammation (Table 5). Similar to alcohol-related liver disease, steatosis is associated with an increased production of reactive oxygen species resulting in lipid peroxidation and activation of hepatic stellate cells. The mechanism for this is not precisely known although recently, steatosis has been shown to alter the expression of mitochondrial membrane proteins, including uncoupling protein2 (6). This protein has been implicated in the generation of reactive oxygen species and lipid metabolism (3). Other studies have suggested a role for leptin and insulin in the relationship between obesity and fibrosis. Serum levels of these hormones are increased in the circulation of obese individuals. Exogenous leptin enhanced the inflammatory and profibrogenic responses in the liver caused by hepatotoxic chemicals (15). In another study, insulin significantly stimulated connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) mRNA in hepatic stellate cells (20) CTGF is a factor involved in the fibrogenic process of various tissues, and is up-regulated in patients with obesity-related fatty liver disease. Despite the limitations of crosssectional studies, the relative risk of fibrosis progression related to BMI in our analysis as well as in the literature is probably indisputable. However, further models particularly based upon longitudinal cohort studies are needed to confirm the current consensus and predict future risk of disease progression. References: 1- Adinolfi LE, Gambardella M, Andreana A et al., Steatosis accelerates the progression of liver damage of chronic hepatitis C patients and correlates with specific HCV genotype and visceral obesity. Hepatology 2001; 33 (6):13581364. 2- Afdhal N H: The natural history of hepatitis C. Sernin Liver Dis 24 Suppi 2: 3-8 (2004). De Torres M and Poynard T Risk factors for liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Ann Hepatol 2003 Jan-Marc; 2(1): 5-11. 3- Arsenijevic D, Onuma H, Pecqueur C et al., Disruption of the uncoupling protein-2 gene in mice reveals a role in immunity and reactive oxygen species production. Nat Oenet 2000; 26 (4): 435-439. 4- Berenguer M: Natural history of recurrent hepatitis C. Liver Transpl. 2002 Oct; 8 (10 Suppl 1): S14-8. 5- Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, NeuschwanderTetri BA, Bacon BR, Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histologic lesions. Am J 6- 7- 8- 9- 10- 11- 12- Gastroenterol 1999; 94:24672474. Cholet F, Nousbaum JB, Richecoeur M, Oger E, Cauvin JM, Lagarde N, Robaszkiewicz M, Gouerou H: Factors associated with liver steatosis and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004 Mar; 28(3):272-8. Clouston AD, Jonsson JR, Purdie DM et al., Steatosis and chronic hepatitis C: analysis of fibrosis and stellate cell activation. J Hepatol 2001; 34(2):314-320. Contos MJ, Garcia N, Sterling RK, Shiffman ML, Luketic V, Sargeant C. The impact of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on the progression of hepatitis C. Hepatology 2001; 34 (Suppl.):1 139. (Abstract). Donato KA. Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of obesity in adults. Arch Inter Med 1998; 158:18551867. Freeman AJ, Law MG, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ.: Predicting progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2003 Jul; 10(4):285-93. Guido M, Bo, Tolotti F, Leandro G. Jara P, Hierro L, Larrauri J, Barbera C, Giacchino R, Zancan L, Balli F, Crivellaro C, Cristina E, Pucci A, Rugge M.: Fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C acquired in infancy: is it only a matter of time? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Mar; 98(3):660-3. Hourigan LF, Macdonald GA, Purdie D, Whitehall VH, Shorthouse C, Clouston A, Powell EE. Fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C correlates 13- 14- 15- 16- 17- 18- 19- significantly with body mass index and steatosis. Hepatology 1999; 29:1215-1519. Hu KQ, Tong MJ. The longterm outcomes of patients with compensated hepatitis C virusrelated cirrhosis and history of parenteral exposure in the United States. Hepatology 1999; 29:1311-1316. Hu KQ, Esrailian E, Runyon B, Thompson K, Chase R, Abdelhalin F, et al. Clinical implication of hepatic Steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 34:187A. Ikejima K, Honda H, Yoshikawa M et al. Leptin augments inflammatory and profibrogenic responses in the murine liver induced by hepatotoxic chemicals. Hepatology 2001 34 (2):288297. Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, Chen TS, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, et al. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptoratic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology, 1981; 1:143-435(8). Kyrlagkitsis I, Portmann B, Smith H, O'Grady J, Cramp ME: Liver histology and progression of fibrosis in individuals with chronic hepatitis C and persistently normal ALT. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Jul; 98(7): 1588-93. McCaughan GW and George J: Fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gut 2004; 53:318-321. Monto A, Alonzo J, Hirsch K et al. Steatosis on liver biopsy in patients with hepatitis C is associated with obesity and diabetes, but not with life-time alcohol use. Hepatology 2000; 32 (4):265A. 20- Paradis V, Perlemuter G, Bonvoust F et al. High glucose and hyperinsulinemia stimulate connective tissue growth factor expression: a potential mechanism involved in progression to fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2001; 34(4 Pt 1):738-744. 21- Rubbia-Brandt L, Quadri R, Abid K et al. Hepatocyte steatosis is a cytopathic effect of hepatitis C virus genotype 3. J Hepatol 2000; 33(1):106-115. 22- Zein NN: Clinical significance of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Clin Microbiol. Rev. 2000 Apr; 13(2):223-35. دراسة زمنية لمعدل وزن كتلة الجسم والتليف وااللتهاب الكبدى فى حاالت االلتهاب الفيروسى المزمن (سى) رضا البدوى ،صبرى أنيس عبده ،جالل معوض محمد ،مجدى جاد، انتصار الشرقاوى ،حسام أمين ،عزة أبو سنة* قسم أمراض الكبد والجهاز الهضمى واألمراض المعدية و قسم الباثولوجيا اإلكلينيكية* كلية طب بنها – جامعة الزقازيق إن الطبيعة المرضية لفيروس (سى) وكذلك العوامل التى تؤدى إلى تقدم الفيروس فى أنسجة الكبدد غيدر معروفة ومازالت قيد البحث .وقد قام قسم الكبد والجهاز الهضمى واألمراض المعدية بكلية طد بنهدا بعمدل د ارسدة عن ذلك ،ووجدد مدن نتداال البحدث أن 3عوامدل :هدى عمدر المدرعض عندد إهدابتف بدالفيروس ووزندف ومعدد ارتفدا خمداار الكبددد ،ALTهدى العوامددل الثةثددة التددى لهددا عةقددة وثيقددة بتليددو الكبددد وتقدددم الحالددة المرضددية ولددذا نوهددى بعمل المزعد من الدراسات للتأكد من ذلك واكتشاف المزعد من العوامل األخرى.