Paper - ILPC

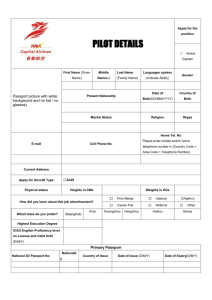

advertisement