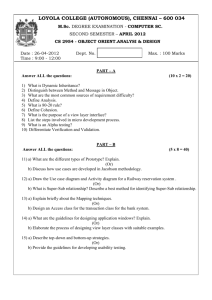

Learning

advertisement

Wasson, Barbara 1997: Advanced Educational Technologies. The Learning Environment, in: Computers in Human Behavior 13: 4, 571-594. D.J. Grosshandler, E. Niswander Grosshandler 2000: Constructing fun: selfdetermination and learning at an afterschool design lab, in: Computers in Human Behavior 16 (2000) 227-240 The authors interpret the interactions at an afterschool and summer learning lab for children in grades 2 through 8. Combining an examination of the activities in a videotaped 2-h segment of an afternoon class with re¯ective commentary by the lead author/teacher, the authors present student and teacher behavior within its particular social context. Through an analysis of student, teacher, and artifact interactions, the authors and that selfdetermination is essential to the construction of fun and learning in the afterschool program. Sims, Rod 1997: Interactivity – a Forgotten Art?, in: Computers in Human Behavior 13: 2, 157-180. Spector, J. Michael and Pal I. Davidson 1997: Creating Rngaging Courseware Using System Dynamics, in: Computers in Human Behavior 13: 2, 127-155. Mikropoulos, Tassos A.: Design, Development and Evaluation of Advanced Learning Environments. An overall Approach This work comments on an overall approach to the design, development and evaluation of advanced learning environments: after a critical review of the related bibliography, it seems that tey are no guidelines and questionnaires for an integrated design and evaluation process, covering all the factors involved and addressed to different groups of evaluators. This article tries to give an overall approach proposing three groups of interconnected factors for the design and evaluation of educational software. These are the information content, the context, and the evaluation process.These groups of factors are represented in three-dimensional graphs. The space under each graph integrates the design and evaluation criteria for educational software. J. Lowyck, J. Pöysä 2001: Design of collaborative learning environments, in: Computers in Human Behavior 17 (2001) 507–516 Designing collaborative learning environments is dependent upon the descriptive knowledge base on learning and instruction. Firstly, the evolution in conceptions of design towards collaborative learning is described, starting from designing as an intuitive behaviour. Secondly, collaborative learning is described from di.erent angles, like individuals-in-context, learner communities, including motivational factors and distributed cognition. It is evidenced that the adequate use of collaborative learning settings may contribute to the learning quality. Thirdly, the implications of collaborative theories on instructional design are outlined, centred around: student, knowledge, assessment and community. The interplay between these perspectives is challenged in new models of (co) design. In the conclusion, an interactive approach of designing environments is advocated. Min Liu 1998: A Study of Engaging High-School Students as Multimedia Designers in a Cognitive Apprenticeship-Style Learning Environment, in: Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 387 ± 415, Educational theory and research have indicated vast potentials of engaging learners as designers. Yet we have much to learn about how to design such a learning environment effectively. This paper reports on a year-long study of investigating how a cognitive apprenticeship-based learner-as-multimedia-designer environment could enhance high-school students' motivation and learning of design knowledge. The study showed that, after participating in such an environment, students became intrinsically more motivated and had more self-confidence. They acquired better understanding of several important design skills. The results indicated that working with a client and designing for a real audience helped to bring about bigger changes in the students' motivation and design knowledge. The study also highlighted the challenges and factors important for designing such a learning environment. Simon Hooper 2002: The e.ects of persistence and small group interaction during computer-based instruction, in: Computers in Human Behavior 19 (2003) 211–220 This study compared the effects of grouping students with di.erent levels of persistence on their ability to learn in cooperative learning groups while working at the computer. A total of 138sixth grade students were classi.ed as high, average, or low in terms of persistence and assigned to dyads. Students completed a workshop on smallgroup interaction methods, a computer-based tutorial, a posttest, and a survey. Results indicated that average persisters interacted more than either high or low persisters. Promotive verbal interaction correlated positively with achievement, and grouping increased partner liking. The implications for forming effective cooperative learning groups is discussed. P.A. Alexander, S.E. Wade 2000: Contexts that promote interest, self-determination, and learning: lasting impressions and lingering questions, in: Computers in Human Behavior 16 (2000) 349-358 Across eight narratives, each capturing unique characteristics of a particular after-school or out-of-school computer program, we identifed several unifying themes. We offer those themes as lingering questions that merit exploration by those invested in these `club' settings. Specifically, we ask about the conceptions of learning held by authors, examine the distinctions between learning about and learning with technology, and question the degree of choice required to sustain the interest and engagement portrayed in these narratives. Cross, Patricia: Leading edge efforts to improve teaching and learning, in: Change, July/August 2001 Six years ago, an article appeared in this magazine that immediately struck a chord. Although the title of the article, “From Teaching to Learning,” has been criticized for making a false separation between teaching and learning, it managed to bundle, in a single phrase, an array of issues that have surfaced in American higher education. In calling for a paradigm shift from teaching to learning, Barr and Tagg (1995) were giving identity to a change that was well under way. There are four major developments driving the call for focusing attention on student learning: • Rising demand from stakeholders—students, parents, employers, and policymakers—for accountability and evidence of student learning. • Significant advances in research on cognition and learning, suggesting that students, rather than teachers, are the active locus for learning. • The arrival in higher education of thousands of students who are unprepared to do collegelevel work. Teachers faced day-by-day with students who are not “getting it” are increasingly interested in knowing how to produce learning. • The growing tendency of students to accumulate their education from multiple colleges and other sources. Thus, students rather than institutions are the units in which learning resides.