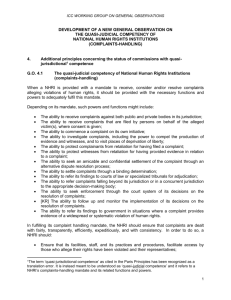

National human rights institutions of all descriptions

advertisement