Stanley Milgram - Obedience Experiment

advertisement

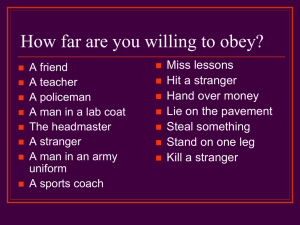

Stanley Milgram's Experiment . ."Obedience and Individual Responsibility" . Stanley Milgram, a psychologist at Yale University, conducted a study focusing on the conflict between obedience to authority and personal conscience. He examined justifications for acts of genocide offered by those accused at the World War II, Nuremberg War Criminal trials. Their defense often was based on "obedience" - - that they were just following orders of their superiors. In the experiment, so-called "teachers" (who were actually the unknowing subjects of the experiment) were recruited by Milgram. They were asked administer an electric shock of increasing intensity to a "learner" for each mistake he made during the experiment. The fictitious story given to these "teachers" was that the experiment was exploring effects of punishment (for incorrect responses) on learning behavior. The "teacher" was not aware that the "learner" in the study was actually an actor - - merely indicating discomfort as the "teacher" increased the electric shocks. When the "teacher" asked whether increased shocks should be given he/she was verbally encouraged to continue. Sixty percent of the "teachers" obeyed orders to punish the learner to the very end of the 450-volt scale! No subject stopped before reaching 300 volts! At times, the worried "teachers" questioned the experimenter, asking who was responsible for any harmful effects resulting from shocking the learner at such a high level. Upon receiving the answer that the experimenter assumed full responsibility, teachers seemed to accept the response and continue shocking, even though some were obviously extremely uncomfortable in doing so. The study raised many questions about how the subjects could bring themselves to administer such heavy shocks. More important to our interests are the ethical issues raised by such an experiment itself. What right does a researcher have to expose subjects to such stress? What activities should be and not be allowed in marketing research? Does the search for knowledge always justify such "costs" to subjects? Who should decide such issues? THE MILGRAM EXPERIMENT Experimental Setup Stanley Milgram 1963 > Milgram puts out a newspaper advertisement offering male Americans around the vicinity of Yale University to participate in a psychology experiment about memory and learning. Upon arriving at Yale, the participant is introduced to a tall, sharp and stern looking experimenter (Milgram) wearing a white lab coat. The participant is also introduced to a friendly co-participant, who is actually a confederate (a person pretending to be a participant, like a rigged audience for a magician). Milgram explains that the experiment investigates punishment in learning, and that one will be the "teacher", and one will be the "learner." Rigged lots are drawn to determine roles, and it is decided that the true participant will be the "teacher." The confederate is strapped to a chair, and his arm is dotted with electrodes. Milgram instructs the teacher to read out word pairs from a list, such as "clear" goes with "air", or "dictionary" goes with "red". Afterwards, when the teacher says a word, the learner must regurgitate the other word that goes with the teacher's word. If the learner recalls the correct word, we move to the next word pair. Otherwise, he is given a voltage shock. These shocks increase in amplitude as more mistakes are made. However, Milgram says that "no permanent tissue damage will occur" (gee how reassuring). Shocks start at 15 volts, and grow in 15 volt increments. The shock generator is rather amusing. It has 30 switches, each labeled with a voltage ranging from 15 through 450 volts, and a verbal rating, ranging from "slight shock" to "danger: severe shock". The final two switches are labeled "XXX". T h e Confederate responds in the following manner to the shocks: voltage confederate response 75 grunts 120 shouts in pain 150 says that he refuses to continue with this experiment 200 blood-curdling screams 300 refuses to answer, mumbles something about a heart condition +330 silence As the participant perceives the confederate's pain, his conscience kicks in, and he begins to object to continuing the experiment. Milgram responds to these objections in the following way: objection milgram's response first "He's fine. go on." second "The experiment requires you to go on." third "It is absolutely essential to go on." fourth "You have no choice. You must go on." Question: What percentage of participants would deliver the full 450 volts? Milgram asked his colleagues this question, and they responded with very small estimates. Maybe about 4 percent. Milgram himself didn't believe anyone would go so far. Experimental Results Milgram's results were alarming. Of the 40 participants he surveyed, 68% of them ended up delivering the full 450 volt treatment. 15 of the 40 ended up convulsing with epilpetic laughter. Participants went temporarily mad and started tearing their hair out. Most amusingly, Milgram actually believed that the aforementioned experimental setup was the CONTROL case! He did not anticipate that subjects would conform at all in these conditions. Explanation - THEORY Situationism > The moral of Milgram's experiment is that behavior is not just a function of personality, but also a function of the situation -- and the latter variable can possess dramatic weight. The bullets directly below detail aspects of Milgram's fabricated environment which made it most persuasive. Entrapment / Gradual Commitment > If I just gave him a 50 volt shock, what's wrong with a 75 volt shock? It's only a little more. If I just gave him a 75 volt shock, what's wrong with a 100 volt shock? It's only a little more ... If I just gave him a 425 volt shock, what's wrong with a 450 volt shock? People can be entrapped into fulfilling ridiculous requests if you just ask them to commit gradually. Mating is another example of entrapment. First you go out for coffee, then you go on a few more casual dates, then you watch TV together, then you make out, and then before you know it, you get married. Objectivity > Milgram told participants that the "learning" experiment was being conducted in the pursuit of science, to study how memory and learning processes work in humans. The scientific theme, combined with the prestige of Yale University and the nontrivial influence of Milgram's lab coat, suggested that participants calmly and objectively complete the study regardless of how the victim was suffering. Do it scientifically. Do it like professionals. Authority Structures > Milgram played the authority figure. It was his experiment. Participants thus believed that any negative ramifications of the experiment would ultimately be blamed on Milgram and not themselves. Furthermore, Milgram was a scientist at Yale. So particpants assumed that he probably knew what he was doing, and everything was going to be alright. Authority structures strip away moral responsibility. Mainpulating Obedience: Methods That Don't Work Reduce Prestige (48%) > The same experiment was conducted at a less prestigious school called Bridgeport. 48% of participants still gave the full 450 V shock. Soften Personality of Authority Figure (50%) > Milgram was a tall, stern, imposing figure with a severe haircut. The experiment was repeated with nicer experimenters. 50% of the participants still gave the full 450 V shock. Mainpulating Obedience: Methods That Do Work Reduce Legitimacy of Authority Figure (20%) > Here there are two confederates: one assigned to be the learner, and another who assists the participant in the "teaching" process. Shortly after the participant arrives, Milgram says he's got something else to do, and asks the participant and teaching confederate, "Why don't you two just finish the experiment yourself?" Milgram leaves. The loony teaching confederate then says that he's got a great idea: let's shock the learner when he gets things wrong! 20% of participants deliver maximum voltage. One way to look at this is as a very positive change. We went from 68% compliance to 20%. But the other way to look at this is with awesome fear. 20% of us will actually blast away another person if a random guy on the street tells us to! Increase Distance From Authority (20%) > When the authority figure is no longer standing next to the participant, but rather sends commands via telephone, 450 V compliance drops to 20%. This phenomenon is also frequently observed in army battles. During WWII, soliders in trenches would fight very cooperatively with their enemies when commanding officers were far away. One side would fire some initial potshots to warn the other side to hide. Then they would shoot a little bit, and quickly return to their trenches. The other side then did the same. Repeat. No one gets hurt! And since the commander isn't there, you can get away with it. Decrease Distance From Victim (30%) > When participants are required to put the learner's hands on the shock plates, or are simply placed closer to the victims, 450 V compliance drops to 30%. Reducing the distance amplifies participants' perceptions of the confederate's pain, stinging their empathy. Another example of this effect occured during the Holocaust. The original master plan did not involve large-scale incinerators and gas chambers, but instead asked that Nazi soldiers be responsibile for rounding up particular families and killing them. This resulted in widespread mutiny and alcoholism among SS soldiers, because they couldn't handle seeing the pain of their victims up close. Add Dissenting Voices (37.5%) > Two confederates assist the participant. One reads a word. Another determines whether the "learner" responds correctly. Finally, the participant is responsible for delivering the shock. At the 150 V mark, the first confederate quits the experiment. At the 210 V mark, the second confederate also quits, leaving the participant with sole responsibility for the shock treatement. 25/40 participants leave at this point. These results are testimony to the power of dissenting voices, and provides insight as to why some dictators throughout history have been so tenacious about eradicating all dissent in their jurisdiction, even in its slightest, most innocent form. An example is Stalin, who deleted everyone who disagreed with him in any way. Aftermath Milgram's quintessential psychology experiment trembled the world. It has been reproduced in many different countries, and is studied in most psychology courses, including two mandatory psychology courses at the US Military Academy. Unfortunately, not much has changed since 1963 in terms of unsound obedience; thousands are killed everyday by automatons who operate under the pretense of simply following orders. An issue raised shortly after Milgram's explosion of fame was whether it was ethical to conduct such deceptive and distressing psychology experiments. Although most of the participants in Milgram's original experiment were very pleased to have participated in such an unforgettable learning experience, one of them was forever traumatized and had great difficulty continuing with his life. Regulations have now been introduced to prevent such psychogical casualties; most notably, the requirement of informed consent, which demands that subjects be told what they will be doing before they actually do it. Whether Milgram's experiment was ethically justified is still the subject of heated debate today. On one hand, it seems inherently unethical. The world certainly learned a lot from it though. However, do the ends justify the means?

![milgram[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005452941_1-ff2d7fd220b66c9ac44050e2aa493bc7-300x300.png)