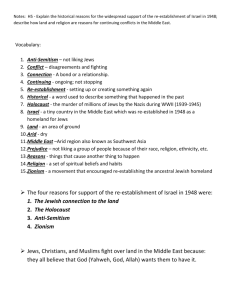

B`Tselem Report - A Policy of Discrimination: Land Expropriation

advertisement