Nicomachean Ethics, REV OUTLINE

advertisement

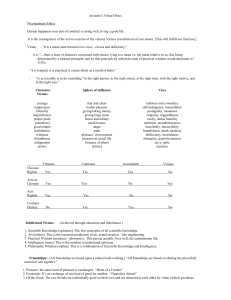

OUTLINE OF ARISTOTLE’S NICOMACHEAN ETHICS (Martin Ostwald translation) by Robert Greene BOOK I Note that the chapter headings are supplied by the translator. They are not in the original text. In a couple of places I have revised the headings slightly. Also, in Book II, I have added to Aristotle’s list of ethical virtues and vices with a modern list of my own. Chapter 1: The good as the aim of action Note the mention of “ends” or “aims” or “goals.” The Greek for “end,” “aim,” or “goal” is télos, and Aristotle’s philosophy is often called “teleology,” or the science of ends, aims, and goals. “Since there are many activities, arts, and sciences, the number of ends is correspondingly large...” (p. 3) Chapter 2: Politics as the master science of the good Politics is the science that rules and manages the other sciences. Its good encompasses theirs and thus is the good for mankind. Chapter 3: The limitations of ethics and politics We mustn’t expect ethics and politics to be as precise as the mathematical sciences, but seek the degree of precision each subject admits. It would be just as silly to accept merely probable arguments from a mathematician as it would be to demand mathematical proofs from a politician! (p. 5) Chapter 4: Happiness is the good, but many views are held about it Most people, both the masses and educated people, agree that the good for humans is happiness. (p.6) But even to pursue it properly, one needs a decent upbringing to begin with. (p. 7) Chapter 5: Various views on the highest good He identifies (p. 8) three basic kinds or ways of life: the life of pleasure, the “political” life, and the speculative or contemplative life. The term politikós, from which we get the word “political,” needs to be explained. Here it means ‘having to do with citizens, civic.’ So “the political life” is a little misleading. It means the life of a citizen, the life of a man of affairs, someone who plays a significant role in the life of the community. Later on, in chapter 13 (p.29, bottom of the page), Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 2 he uses the same expression. “Thus, the student of politics (politikós) must study the soul, but he must do so with his own aim in view, and only to the extent that the objects of his inquiry demand...” Here politikós could be rendered as ‘the good citizen’ or ‘the person wishing to be a good citizen.’ This raises the question of who was Aristotle’s audience for the lectures that comprise these texts: young men of the upper or upper middle class who were among the relatively few to receive a high-class education in Athenian society. Note how undemocratic he sounds on p. 8: “The common run of people (hoi polloi, the many or the masses)...betray their utter slavishness in their preference for a life suitable to cattle...” Chapter 6: Plato’s view of the Good This chapter is a critique of Plato’s theory of forms, in particular the concept of the Good that we read about in The Republic. Plato thinks there is one single form of the Good of which all good things partake. Aristotle thinks his teacher, Plato, is wrong about this: “The good...is not some element common to all these things as derived from one Form.” (p. 13, pgh 1) We call different things “good” by analogy (p. 13, pgh 2) He leads up to this with several arguments against Plato’s view that there is one single form of Good. He also distinguishes (p. 12) between that which is good as a means and that which is good in itself, or good as an end in itself. It is not easy to decide whether Plato or Aristotle is right in this controversy, but at least we can get some idea of their different views. Chapter 7: The good is final and self-sufficient; happiness is defined “[W]e always choose happiness as an end in itself and never for the sake of something else.” (p. 15, pgh 1) p. 16, pgh 2: How can it be that a carpenter and a shoemaker has a proper function, but that a human being as such doesn’t have one? Or how can the eye, the hand, the foot, etc. each have their proper functions, but the individual as a whole does not? p. 17, pgh 2: a thing and a good thing are generically the same. In other words, when something most fully attains its natural function, that’s what we mean by calling it a good thing. Chapter 8: Popular views about happiness confirm our position The virtuous man is happiest, but we also need external goods. Chapter 9: How happiness is acquired Humans can be happy, but not animals. Even children can’t truly be happy. Aristotle seems a bit grumpy here. Surely children may have a measure of happiness, but not to the same extent as when they reach their full human nature. Still, we notice him starting to circumscribe happiness here, and this continues in the next chapter. Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 3 Chapter 10: Can a man be called “happy” during his lifetime? We can’t be completely sure someone has been happy until he reaches the end of his life because a great enough misfortune can wreck his life. Still (p. 25), “activities in conformity with virtue constitute happiness,” so that the virtuous person can withstand misfortune and find a measure of happiness. Chapter 11: Do the fortunes of the living affect the dead? Not very much. Chapter 12: The praise accorded to happiness We honor happiness rather than praise it. Chapter 13: The psychological foundations of the virtues In this chapter he gives a simplified explanation of the nature of the psyché or “soul,” contrasting its rational and irrational parts. The latter is divided into two parts (p. 31, pgh 2), the vegetative and the part containing appetite and desire. The former also has two parts, the one possessing reason within itself, the other listening to reason. At the end of this chapter (p. 32) he makes an important distinction between ethical or moral virtue, which has to do with a person’s character and behavior, and intellectual virtue, which consists of wisdom (sophia), intelligence (synesis), and practical wisdom (phronesis). “Practical wisdom” means common sense, good sense, prudence. To be intelligent is to be smart or quickwitted, the sort of thing IQ tests attempt to measure. Wisdom is something deeper and more than just quickwittedness; it is insight, imagination, creativity. Books II-V deal with ethical virtue, and Book VI with intellectual virtue. Book VII discusses moral weakness and pleasure. Books VIII and IX provide a detailed analysis of “friendship,” i.e. social relationships of nearly all kinds. Book X concludes with a detailed comparison of pleasure and happiness and the bíos theoretikós, the speculative or contemplative life, the one Aristotle regards as the highest and most like the divine. BOOK II Chapter 1: Moral virtue as the result of habits Intellectual virtue comes chiefly from teaching. Moral virtue, ethiké areté, is formed by habit, as the name shows, being derived from ethos, habit. We become just by practicing just actions, etc. By acting bravely in the face of danger we become brave. Chapter 2: Method in the practical sciences Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 4 We are not conducting this inquiry in order to know what virtue is, but to become good—why else do this? Thus, we must examine actions and how they should be performed, for it is actions that develop habits. However, this is only an outline, as we said earlier (I, 3). In every situation, the agent must consider the particulars. Moral qualities are destroyed by defect and excess. First statement of the mean. Individual virtuous actions lead to the development of virtue. Chapter 3: Pleasure and pain as the test of virtue Moral virtue is concerned with pleasure and pain: pleasure makes us do base actions and pain prevents us from doing noble actions. The pleasure and pain we feel in doing or not doing virtuous actions are a gauge of whether or not we are virtuous. Pleasure and pain accompany every emotion and every action. A good man will feel pleasure and pain at the right time, to the right extent, in the right way. The actions that produce virtue also will develop it, together with the corresponding pleasures and pains. Chapter 4: Virtuous action and virtue The agent must know what he is doing, must choose to act as he does, and for its own sake, and the act must spring from a firm and unchangeable character. Meeting all these qualifications requires action and repeated action, not merely knowledge. Chapter 5: Virtue defined: the genus In the soul there are a) emotions, sense-perceptions and memories (pathé) b) powers or faculties (dynameis), c) dispositions to think or act in certain ways, in other words, traits, characteristics, or simply habits (hexeis). An ethical virtue is a disposition or characteristic or habit. In other words, ethical virtues are good habits and vices are bad ones. Chapter 6: Virtue defined: the differentia Ethical virtue or excellence is a mental disposition that inclines one to choose the mean between two vices relative to us, a mean defined by a logos or rational principle, such as a reasonable person would define or determine it. Chapter 7: Examples of the mean in particular virtues Virtues mentioned: courage, self-control, generosity, magnificence, magnanimity, “gentleness,” honesty, wittiness, friendliness, modesty, righteous indignation. Chapter 8: The relation between the mean and its extremes the extremes are more opposed to each other than each is to the mean Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 5 In some cases it is the deficiency and in others the excess that is more opposed to the mean. Chapter 9: How to attain the mean It is hard to behave as we should to the right person, to the right extent, at the right time, for the right reason, and in the right way. First of all, avoid the extreme that is more opposed to the mean; that is, take the lesser evil. Then we must watch for the errors we as individuals are more prone to. We come to recognize our inclinations by observing the pleasure and pain produced in us by the different extremes. Then we steer in the opposite direction and try to overcompensate for our inclinations. Even observing all these counsels, it still is hard to hit the mean and even harder when all we know is the definition. But still, that’s a start. ARISTOTLE’S LIST OF ETHICAL VIRTUES AND VICES The virtues and vices immediately below are the ones listed and described in the Nicomachean Ethics. Following are a set of additional virtues and vices that reflect contemporary Western culture. Some of them might have been considered as such by Aristotle, and some might not. Moreover, as Aristotle observes, some of the virtues and vices do not have specific names, and we have to supply a name or description. Excess (Vice) The Mean (Virtue) Deficiency (Vice) recklessness courage cowardice self-indulgence, wantonness moderation, temperance asceticism extravagance generosity, liberality stinginess vulgarity, ostentatiousness magnificence, suitable expenditure cheapness, meanness vanity, conceit magnanimity, highmindedness, greatness of soul pettiness, smallmindedness excessive ambition the mean in the pursuit of honors lack of ambition bad temper gentleness, good temper apathy, passivity obsequiousness friendliness, pleasantness, ability to get along honesty, frankness, candor surliness,grouchiness boastfulness excessive modesty Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 6 silliness, tactlessness, boorishness tastefulness, tact, wittiness lack of a sense of humor shamelessness modesty, proper sense of shame bashfulness, shyness doing injustice justice, acting justly suffering injustice VIRTUES AND VICES TO SUPPLEMENT ARISTOTLE’S LIST As Aristotle notes, some of the virtues and vices don’t have specific names, and you have to use a descriptive phrase to name them. Also, in some cases there may be difficulty in deciding which vice is the excess and which the deficiency. It depends on how you define the virtue. Here are some additional virtues and vices (good and bad habits) that we might add to fill out Aristotle’s list. Excess Virtue Deficiency smugness confidence lack of confidence overpunctuality punctuality lack of punctuality fussiness orderliness, neatness sloppiness obsessive-compulsiveness self-discipline laxness excessive orderliness being well-organized disorganization severity or harshness discipline laxness overconscientiousness, being a workaholic diligence laziness being a gossip interest in others indifference to others officiousness, being a busybody helpfulness unconcern hastiness or: being too slow to act promptness in action promptness in action procrastination lack of deliberateness excessive tolerance fairness prejudice greed, avarice proper attitude to money unconcern with money Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 7 excessive politeness, effeteness politeness rudeness, brusqueness unctuousness, effeteness pleasantness coarseness overbearingness, being a bully manliness effeteness masochism, sado-masochism assertiveness endurance, stamina modesty softness, weakness shyness pomposity, ceremoniousness decorum, dignity excessive informality hypercleanliness hypochondria good personal hygiene concern for one’s health sloppiness neglect of one’s health overly strict parenting, abusive parenting good parenting neglect of one’s children greed proper attitude to money insufficient interest in money being materialistic proper attitude toward possessions carelessness about possessions nervousness, hyperactivity alertness, alacrity phlegmaticness, stodginess excessive haste sense of pace or rhythm lethargy inflexibility, stubbornness perseverance, assiduousness flightiness being guilt-ridden, excessive self-criticism proper sense of guilt, self-criticism being un-self-critical excessive sense of shame proper sense of shame shamelessness egotism proper “self-love” self-hatred cynicism sophistication naïveté paranoia prudence or caution in dealing with others being too trusting of others Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics overconscientiousness, compulsiveness 8 conscientiousness irresponsibility BOOK III In the first five chapters of Book III, Aristotle makes a complicated set of distinctions between a) voluntary and involuntary acts in general and b) actions done due to (or because of) ignorance and actions done in ignorance. He also speaks of actions that are “non-voluntary” (as the translator Ostwald calls them) or more literally, “not voluntary.” This is all less complicated than it seems if one takes the trouble to look at the distinctions carefully. Actions done under constraint or due to ignorance are involuntary. In an act done under constraint, the source of motion comes from without and the person compelled contributes nothing. Mixed actions: partly under constraint, but essentially voluntary, like jettisoning a cargo in a storm. All acts due to ignorance are not voluntary, but they are involuntary only when they are followed by sorrow and regret (ch. 1, p. 55). In other words, if you knew, you wouldn’t have done them. Acting due to (through or because of) ignorance (di’ agnoian) is different from acting in ignorance (agnooûnta – not knowing, being ignorant). Acting due to intoxication or anger is acting in ignorance, that is of the particular circumstances in which one acts or refrains from acting. While this kind of ignorance can make an act involuntary, ignorance of principles like that of not stealing is not involuntary—it is wicked. Every wicked man is ignorant of what he should and should not do. The terms “voluntary” and “involuntary” are to be used with reference to the moment of action. Actions belong among particulars, and particular acts such as the one above are performed voluntarily unless one is physically constrained to do them (or from doing them). In other words, we have “free will” because we have the power to initiate action, that is, to move our own bodies freely and to think, to reflect about what we are going to do. In chapter 5, one of the most important chapters in the book, Aristotle explains the ultimate motive of our actions: we pursue the good as it appears to us (to phainómenon agathon). Hence, it is crucial for human beings that our vision of the good approximate as much as possible to what is truly good. If it does, we can truly be said to be well endowed by nature. In placing so much importance on our vision of the good, Aristotle clearly shows the influence of Plato on his thought. Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 9 In the remaining chapters of Book III, Aristotle gives a fuller discussion than in Book II of the two most important moral virtues, courage and self-control (that is, temperance, moderation in the pursuit of sensual desires). THE SYLLOGISM AND THE PRACTICAL SYLLOGISM In discussing various issues and problems, we make use of different kinds of reasoning. In inductive reasoning, we form generalizations from individual examples. In deductive reasoning, we derive a conclusion from premises. Usually an issue can be summed up in a controlling syllogism, associated with which will be subordinate arguments. Often there is broad agreement about the major premise, a generalization, although defining the terms may be a problem. Then most of the discussion focuses on establishing the minor premise, usually a statement of fact. In the practical syllogism, which we use in deliberating about an action that we are contemplating, the conclusion is equivalent to the act, or we might simply say, the conclusion is the act.1 Between stating an argument in ordinary language and restating it in the symbols of formal logic, the transition sometimes is tricky. The examples below illustrate how it may occur. All [Middle term] is/are [Predicate term]. MAJOR PREMISE This [Subject term] is MINOR PREMISE [Middle term]. Therefore, [Subject term] is [Predicate term]. CONCLUSION The bracketed terms can be represented simply by letters: All B is C. This A is B.2 Therefore, this A is C. In the practical syllogism, as Aristotle says (Nicomachean Ethics, VII, 3, p. 183 in the Ostwald translation), “When two premises are combined into one…the soul is thereupon bound to affirm the conclusion, and if the premises involve action, the soul is bound to perform this act at once.” Aristotle then gives an example of a practical syllogism: Everything sweet ought to be tasted. This thing before me is sweet. In Ostwald’s edition, the practical syllogism is explained in two footnotes: the first in Book III, ch. 1, p. 55, and the second in Book VII, ch. 3, p. 181. 2 The minor premise is considered by some logicians to be a universal proposition, i.e., it refers to all members of a class containing only one member. This is called a “singular proposition.” 1 Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 10 This thing ought to be tasted. (Assuming you’re hungry and there’s no reason for you not to act or anything restraining you from acting, the conclusion is equivalent to the act.) BOOK IV In Book IV, Aristotle completes his list of ethical virtues and vices (See table above, in Book II, for the list of all of them), except for the supreme virtue, justice, to which he devotes all of Book V. BOOK V Book V is devoted to the supreme ethical virtue, justice, which, Aristotle explains, encompasses all the others. In the concluding passage of chapter 1, he explains its nature: [I]n one sense we call those things ‘just’ which produce and preserve happiness for the social and political community….Thus, this kind of justice is complete virtue or excellence, not in an unqualified sense, but in relation to our fellow men. And for that reason justice is regarded as the highest of all virtues…and, as the proverb has it, “In justice every virtue is summed up.” It is complete virtue and excellence in the fullest sense, because it is the practice of complete virtue. It is complete because he who possesses it can make use of his virtue not only by himself but also in his relations with his fellow men; for there are many people who can make use of their virtue in their own affairs, but who are incapable of using it in their relations with others….Now, the worst man is he who practices wickedness toward himself as well as his friends, but the best man is not one who practices virtue toward himself, but who practices it toward others, for that is a hard thing to achieve. Justice in this sense, then, is not a part of virtue but the whole of excellence or virtue, and the injustice opposed to it is not part of vice but the whole of vice. The difference between virtue and justice in this sense is clear from what we have said. They are the same thing…insofar as it is exhibited in relation to others it is justice, but insofar as it is simply a [mental] disposition of this kind, it is virtue. At the end of chapter 2, he gives a list of unjust acts: “theft, adultery, poisoning, procuring, enticement of slaves, assassination, and bearing false witness…assault, imprisonment, murder, violent robbery, maiming, defamation, and character-smearing.” In other passages in Book V, we see him anticipating other ethical theories, which he easily integrates into his conception of justice: ch. 5: “[I]t is by their mutual contribution that men are held together.” Here and elsewhere he sounds like a social contract theorist. ch. 5: “For a community is not formed by two physicians, but by a physician and a farmer, and, in general, by people who are different and unequal. But they must be equalized; and hence everything that enters into an exchange must somehow be comparable. It is for this purpose that money has been introduced…For it measures all things <not only their equality but also the amount by which they exceed or fall short <of one another>. Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 11 Thus it tells us how many shoes are equal to a house or to a given quantity of food.” In describing this type of calculation, Aristotle sounds like a Utilitarian. ch. 10: “[L]aw is always a general statement, yet there are cases which it is not possible to cover in a general statement. In matters therefore where, while it is necessary to speak in general terms, it is not possible to do so correctly, the law takes into consideration the majority of cases, although it is not unaware of the error this involves. And this does not make it a wrong law; for the error is not in the law nor in the lawgiver, but in the nature of the case: the material of conduct is essentially irregular.”3 Here we have Aristotle’s solution to the problem of the inflexibility of moral laws that commentators on Kant have wrestled with. BOOK VI Now Aristotle discusses at length intellectual virtue or excellence, which he identified in Book I, ch. 13. Our actions aren’t guided solely by habit, but by thought, and he needs to expand upon the three types of thinking, which enable us to gain scientific knowledge on the one hand and to distinguish right and wrong on the other. For example, if we are going to improve ethically, to get rid of our bad habits and cultivate good ones, we have to identify them so that we can know what they are. The discussion of intellectual virtue in Book VI leads naturally into that of moral strength and moral weakness in Book VII because his answer to the problem of moral weakness seems to depend in large part on intellectual virtue. Here, as elsewhere, Aristotle shows the influence of Plato. BOOK VII, 1-3 1. Moral strength and moral weakness: their relation to virtue and vice and current beliefs about them Aristotle groups bad qualities of character into three categories: vice, moral weakness, and brutishness or bestiality. He has already discussed vice in Books II-V. Brutishness or bestiality is more extreme than mere vice. It is depravity, which includes such activities as cannibalism and human sacrifice. At the other end of the scale is a virtue so great that it resembles the divine, a kind of holiness or saintliness. Most people fall in between these two extremes. But we are not only prone to vice, but to akrasía or akráteia, “moral weakness.” These words can also be translated as “lack of self-discipline” or “lack of self-control.” The opposite is enkráteia, “moral strength” or “self-discipline” or “self-control.” which is different from mere “moderation” or “temperance,” which he discussed in Book III.4 3 The translation of this passage is that of Rackham in the Loeb Classical Library edition of the Nicomachean Ethics. 4 In Book III, the translator Ostwald renders sophrosýne as “self-control,” but this is not the way most translators translate this word. They and the standard ancient Greek dictionary give it as moderation or temperance. On p. 314 of the glossary Ostwald argues that ‘moderation’ and ‘temperance’ sound too negative, but this is unconvincing. While ‘temperance’ does bring to mind abstention from alcoholic beverages, Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 12 In Book II, ch. 9 Aristotle tells us how to find the mean between two vices so that we can correct our vices. This presupposes that we recognize a given vice, that we want to change it, and that we are trying to do so. To remove our vices, we first need to recognize them, a process that requires intellectual virtue, that is, some combination of wisdom, intelligence, and good sense.5 These qualities are described at length in Book VI. Now in Book VII, he asks why some of us—or all of us at times—are unable to resist a vice when we know we should. This is “moral weakness.” In chapter 1 he explains the syndrome: a morally weak man tends to abandon his calculation of what he should do. (p. 175, pgh 3. The rest of this paragraph is hard to follow.) 2. Problems in the current beliefs about moral strength and moral weakness Here Aristotle states the main problem he sets for himself in regard to moral weakness: In Plato’s dialogue Protagoras, Socrates argues that it is strange if, when a man has knowledge, something else should overpower it and drag it about like a slave. In other words, Socrates thinks it doesn’t make sense to say, “I know what I should do, but I just won’t or can’t do it.” As Aristotle says, this theory is plainly different from the observed facts. Lots of people say they know they should give up drinking or some other bad habit, but they don’t do it. So what is the solution? Is Plato wrong on this point? Aristotle offers a solution to this problem in chapter 3. 3. Some problems solved: moral weakness and knowledge Do morally weak people act knowingly or not, and if knowingly, in what sense? Note that the morally weak person is different from the akólastos, the self-indulgent, profligate, licentious, dissolute person. That person is led on by his own choice, because he believes on principle that he should always pursue the pleasures of the moment. By contrast, the morally weak person doesn’t think he should do so, but still he does so. An example of the practical syllogism: Everything sweet ought to be tasted. This thing before me is sweet. This thing ought to be tasted. In the presence of desire, the conclusion turns into the act of tasting. The major premise “Not all sweet things should be tasted” never makes its way into a practical syllogism. It is defeated by the above syllogism, which is powered by desire or appetite. Hence, the morally weak person is like someone who is half asleep or asleep, or mad, or drunk. He may utter the above premise, but it is ineffective. ‘temperate’ and ‘moderate’ do not. A person moderate in his or her desires has this quality “without effort or strain,” as Ostwald defines the trait, so that his substitution of “self-control” for it doesn’t make sense. 5 The word phrónesis is translated by Ostwald as “practical wisdom.” More familiar synonyms of this phrase are “prudence,” “common sense,” and “good sense.” As we all know, a person can be extremely intelligent, even wise, but lack practical common sense. Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 13 If you recognize your moral weakness, how do you combat it? It’s not exactly like overcoming a vice in Book II, 9, where you overcompensate. Here the process seems to require a kind of psychoanalysis. You need to stay awake, so to speak, so that the major premise (that is, the principle, the moral command) can be strong enough to help you resist the desire. In the remaining chapters of Book VII, Aristotle discusses moral strength and moral weakness in further detail. In the last few chapters, he begins the discussion of pleasure which he completes in Book X (See below). NICOMACHEAN ETHICS – BOOKS VIII & IX What exactly is friendship? It consists of an emotion or emotions, a state or condition, a relation, and a variety of actions. The emotional element is two (or more) people a) wishing good for each other, b) experiencing pleasure from each other, and c) admiring each other. They also d) do things for each other and benefit from each other in various ways. Aristotle observes that a friend really is another self (IX, 4, p. 253). This suggests another set of positive emotions: friends gain a sense of power at expanding their being to each other and a sense of fulfillment in doing things for each other. Also, if someone you like and admire likes and admires you, you derive pleasure from the compliment you are being paid. It is clear from Aristotle’s discussion that true friendship, like virtue and happiness in the fullest sense, is not easily obtained. (See VIII, 3, p. 220.) That makes it all the more valuable and all the more precious when it does occur. On the one hand, when we judge any of these things by the highest standard, we may become strongly aware of the many imperfections with which our lives are filled and feel frustrated and disillusioned. But then, looking at things from a more positive standpoint, we can appreciate the good things we have all the more because of their excellence and their rarity, because we can’t take them for granted. We can be glad that for those of us privileged to enjoy the full exercise of our faculties, the good life is at least partly attainable and is worth striving for. As noted earlier in the course, Aristotle’s ethics is very much an ethics for optimistic, idealistic, active people like Americans. It is not an ethics of pessimism, cynicism, and resignation. 1. Why we need friendship Why do we need friendship? It is clear that no one would choose to live without friends, even if he had all other good things. The desire for friendship seems to be implanted in us by nature. Friends enhance our ability to think and to act. Friendship holds societies together. When people are friends, they have no need of justice, but when they are just, they need friendship in addition. But is friendship based on like being attracted to like or is it opposites that attract? Can everybody be friends, including wicked people, or can only good people be friends? Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 14 The above are introductory observations Aristotle makes. In later chapters, he points out that some of the strongest friendships are between people who are unlike, for example, between parents and children. The friendship between man and wife also is between people who are in part unlike. The question is whether either principle is more fundamental to friendship than the other: like to like or opposite to opposite. We can think of other examples of these principles: people who start out as enemies sometimes overcome their hostility and become very close friends. We tend to think of friendship as most essentially the emotion of liking or love that friends feel for each other, and we can ask, what is the nature of that emotion and what causes it? But we should also keep in mind that friendship consists of action as well as emotion, as exemplified by Jesus’ saying, “Greater love than this no man hath, that he lay down his life for his friend.” 2. The three things worthy of affection We don’t feel affection for everything, but only the things that are worthy of affection; that is, we don’t like or love everything, but only the things that are likeable or lovable. Three types of things fall under this heading: the things that are useful, or pleasant, or good. Of course you can like or love inanimate objects as well as people. You might love your house or your car or your clothing or some other possession, but you’re not friends with them. Furthermore, we frequently like or admire some other persons or groups of people, for example, an athlete, entertainer, musical group, or athletic team, but that’s not enough to make us friends with them. The good will we feel not only has to be reciprocated, but each party has to be aware of the mutual good will for a friendship to exist. A complex set of intercommunications must take place before an actual friendship is formed: “Therefore, to be friends people must wish each other well and be aware of each other wishing each other well for one [or more] of the reasons mentioned above.” (See p. 218, the final sentence of ch. 2) 3. The three kinds of friendship In outlining the three basic types of friendship, Aristotle once again is providing a framework with general types. Actual friendships may or may not represent the pure types. More often than not, they will be mixed. Business associates may be friends because they are useful to each other, and it may go no farther than that, but they may also admire each other’s skills, and as they come to know each other better, they may admire each other’s character. Furthermore, the friendship based on areté, “virtue” or “excellence,” doesn’t mean just moral virtue or excellence. It means excellence of any kind. (See Glossary, pp. 303304.) You might admire your friend because he/she is a very good athlete, or writer, or singer, or as a person of good character, or both. The highest kind of friendship would very likely include the other two kinds. (See p. 220, first pgh.) 4. Perfect friendship and imperfect friendship Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 15 To be friends on the basis of pleasure and usefulness is also possible for bad people, but only good people can be friends on the basis of what they are, for bad people don’t find joy in each other unless they see some advantage in it. (pp. 221-222) This implies that you can judge a person’s character by the type of friendships he has. Stalin, for example, had many of his old comrades executed in his purges. He doesn’t sound like the kind of man you could be true friends with. Nor is it clear whether Hitler had any close friends—perhaps only among his closest cronies. Strictly speaking, true friendship is based on mutual admiration and affection for virtue. The other two bases for friendship are called friendship because of their similarity to the true kind. This doesn’t mean that you don’t like somebody who is useful to you or enjoyable to be with, but the friendship tends to be superficial. This further suggests that even with types of friendship to which we are strongly inclined by nature—the friendship between parents and children and that between siblings—the relationship is never automatic. Trust always has to be earned. 5. Friendship as a characteristic and as an activity Friendship is both a “characteristic” and an activity. “Characteristic” is the word Ostwald uses to translate “héxis.” (See Glossary, pp. 308-309). He notes that “habit” has often been used to translate this word, and that is the meaning given by the standard ancient Greek dictionary. It also means ‘a state of mind’ and ‘a trained habit or skill.’ Perhaps it is clearer to call friendship a mental disposition or state of mind. However, it is more than that. Even when friends are separated, they may remain well-disposed to each other, but friendship is fully actualized or realized when friends share each other’s company and do good things with and for each other. (The word enérgeia means ‘actualization, actuality, activity,’ but the actualization of friendship is the activity of sharing each other’s company, doing things together, helping each other.) Friends show affection for each other, but friendship is more than just affection. It seems to be a héxis, an enduring mental disposition or habit. In loving a friend, we love our own good, for the good man in becoming dear to another becomes that man’s good. Book IX 4. Self-love as the basis of friendship All the characteristics of friendship that friends have toward each other a good man has toward himself. At the beginning of the chapter Aristotle summarizes these characteristics and then explains how the good man has them in relation to himself. But he has the same attitude toward his friend as he does toward himself because a friend is essentially another self (p. 253) A good person loves himself, but this is not an egoistic self-love because almost by definition a good person has friends like himself whom he loves as himself. By contrast, wicked people, insofar as they are wicked, avoid, so to speak, their own company. They don’t love themselves nor do they love their friends. Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 16 PLEASURE AND HAPPINESS BOOK VII, 11-14 11. Pleasure: some current views 12. The views discussed: (1) Is pleasure a good thing? 13. The views discussed: (3) Is pleasure the highest good? The bodily pleasures have claimed the name ‘pleasure’ for themselves as their own private possession because everyone tends to follow them and partakes of them more frequently than of any others. 14. The views discussed: (2) Are most pleasures bad? The pleasures of the body are pursued because of their intensity by those incapable of enjoying other pleasures. (p. 211) BOOK X 1. The two views about pleasure Pleasure and pain pervade life. One school of thought asserts that pleasure is the good and another the opposite view that it is utterly bad. 2. Eudoxus’ view: pleasure is the good Pleasure is desired both by non-intelligent and intelligent creatures. (p. 275) 3. The view that pleasure is evil The mere fact that bad people seek certain pleasures is comparable to a sick person finding different things pleasant from a healthy person. 4. The true character of pleasure Just as vision is complete at any moment, so is pleasure. (p. 279) “The specific kind of pleasure is complete at any time [it occurs].” (p. 280) “Pleasure completes the activity, not as an inherent condition, but as an added end, like the bloom of youth in those who are in their prime.” (p. 281-282) “[T]here is no pleasure without activity, and every activity is completed by pleasure.” 5. The value of pleasure Outline of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 17 Pleasure is neither a thought nor a sense-perception—that would be absurd, but because they never occur separately, people think they are identical. Cp. Book II, 3 (p. 37): “Pleasure and pain accompany every emotion and every action.” Cp. also IX, 9 (p. 266): “Life is in itself good and pleasant. We can see that from the very fact that everyone desires it, especially good and supremely happy men.” 6. Happiness and activity 7. Happiness, intelligence, and the contemplative life Scholars have had some difficulty translating the phrase bios theoretikos. The adjective theoretikos is derived from the noun theoria. We have to be careful about translating these words because they don’t mean ‘theoretical’ or ‘theory,’ the words we get from them. Ostwald translates theoría as ‘study,’ and theoretikós as ‘contemplative.’ This is confusing. However, the fuller explanation of these terms on p. 315-316 of his glossary is clearer and makes more sense. The bios theoretikos is the life of study and research, in other words, the intellectual life, the life of the mind. That’s what Aristotle regards as the highest life for human beings because it is the activity of the highest part of our nature, that part of us that most resembles the divine, as he conceives it. Cp. Book XII of the Metaphysics, where he describes the life of God or the divine as “a thinking on thinking.” (Now we need to consider what that might mean.) Of the divine he also says, “Its life is like the best we temporarily enjoy.” (XII, ch. 7) 8. The advantages of the contemplative life Since we are mere mortal humans, we aren’t capable of living in a way that totally resembles the divine. Our lives are a mixture of the three lives he described in Book I, ch. 5. 9. Ethics and politics Individuals do not pursue the good life in isolation, but together with our fellow humans. Hence, ethics is a branch of politics and the study of the one leads naturally into the other. © Robert Greene Eau Claire, Wisconsin 2012