Andrea Fineman Prof. Scott FA 174 21 April 2010 Museum without

advertisement

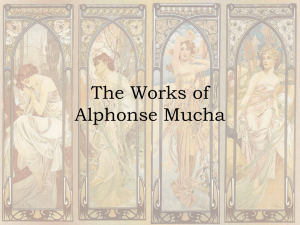

Andrea Fineman Prof. Scott FA 174 21 April 2010 Museum without walls paper: First draft In many academic texts on Art Nouveau, the Arts and Crafts movement is seen as a group of artists who have stylistic and ideological connections to the core Art Nouveau artists, but with a slightly different focus. Though stylistically the two movements are highly similar, there is serious ideological tension between the two movements. An aesthetic vision, shaped by the industrial revolution of the 19th century, is at the core of both movements; however, the ends to be achieved through forms differ greatly between the two groups. The Arts and Crafts artists sought to create a more socially just society through the popularization of handcrafted decorative pieces and other consumer goods—often, their work and ideology takes on a medievalist and religious tone. The Art Nouveau artists, on the other hand, didn’t avoid modern technology as wholly evil. Instead, they sought to create a “total work of art” by breaking ties with older styles of art and turning to art, decoration, and consumer goods that embodied the modern Art Nouveau style. Henry van de Velde’s home in Uccle, Belgium is a famous example of the Art Nouveau “total work,” or gesamtkunstwerk: according to Peter Selz, Toulouse-Lautrec was once invited to a meal at van de Velde’s home, and found the food chosen to correspond in color and texture with the table setting and interior decorations of the dining room.1 For a movement that finds itself in an ideological debate with its sister movement, it’s not surprising that the Arts and Crafts movement stems from the work of a couple of prominent English ideologues. John Ruskin and William Morris, both of whom wrote extensively on art and aesthetics, are arguably the most influential figures in the development of the Arts and Crafts 1 Peter Selz, introduction to Art Nouveau: Art and Design at the Turn of the Century, Peter Selz and Mildred Constantine, eds. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1959), 8. movement. Ruskin and Morris believed that the elaborate, machine-made decorative consumer goods flooding the markets during the second half of the 19th century were “dishonest” in terms of forms and materials, and that the system of manufacturing that created them was dehumanizing for the factory workers who participated in it.2 Their solution, practiced to varying degrees of success by their followers, was to create consumer goods through a medieval-inspired system of guilds, where artisans would work together in workshops to create hand-crafted items that bore the mark of a skilled craftsman’s hand. Thus, the workers responsible for creating consumer goods would find fulfillment rather than become dehumanized by a factory system. Developing a way to create “honest,” hand-crafted goods that were affordable enough for those same working-class people they were trying to save from dehumanization was always a struggle for the Arts and Crafts theorists. The stylistic origin of Arts and Crafts is much in line with that of Art Nouveau’s, and the two styles’ visual similarity is the reason why they are so often lumped together. The artistic works of William Blake are often cited as the earliest foundation of both Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau. Blake, known primarily as a Romantic poet who illustrated his own works with fantastical drawings and paintings, worked in a curving, linear style that fascinated Dante Gabriel Rossetti, an English artist known for his connection to the Pre-Raphaelite movement, born just one year after Blake’s death. Through Rossetti, another Pre-Raphaelite artist, Edward Burne-Jones, became interested in Blake’s work.3 Burne-Jones was a member of William Morris’s circle and, like Morris, sought to create art in a “medieval” paradigm. Included in Morris’s ideology is an emphasis on the importance of utilitarian art—furniture and housewares rather than paintings—an element of Arts and Crafts ideology that was picked up by many Art 2 3 Jonathan M. Woodham, Twentieth Century Design (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 11. John Russell Taylor, The Art Nouveau Book in Britain (London: Methuen and Co. Ltd., 1966), 27. Nouveau artists. However, the Art Nouveau artists’ interest in utilitarian objects stems from their emphasis on the gesamtkunstwerk and the production of household objects to match the Art Nouveau aesthetic, and in so doing elevating the decorative and applied arts to the level of fine art—the social justice and moralistic elements of Morris’s teachings are less of a focus for the Art Nouveau artists. The tendency of Art Nouveau away from morality stems in part from an earlier movement that, like Arts and Crafts, also developed in Britain. The Aesthetic Movement, an artistic movement that prized the importance of beauty over moral issues and held to the concept of “art for art’s sake”—an idea thoroughly rejected by William Morris—helped popularize the curved line and naturalistic forms of Art Nouveau in a way that appealed to a broad section of the middle class.4 The followers of the Aesthetic Movement also helped popularize a taste for Japanese art, which proved to be an important influence on Art Nouveau form. Oscar Wilde, the British playwright, embodied the symbol of the Aesthetic Movement: the dandy, a character similar to the French Impressionists’ flaneur, characterized by stylish dress, wit, and connections to high society. Though the Aesthetic Movement’s ideological goals were far removed from those of the Arts and Crafts practitioners, the forms they used in their designs were rather similar, and their artistic output was quite similar as well. Both the Arts and Crafts and the Aesthetic Movements produced experimental publications that furthered their ideology as well as advertised their style, with experimental typography and layouts and articles and essays of diverse types.5 Aubrey Beardsley, a British Art Nouveau and Aesthetic Movement artist, headed the journal The Yellow Book, while A. H. Mackmurdo, an Arts and Crafts artist and friend of Ruskin, edited the journal The Hobby Horse, and Morris and Charles Robert Ashbee, another 4 5 Stephen Escritt, Art Nouveau (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2000), 53. Selz, 8. follower of the Arts and Crafts Movement, led publishing houses dedicated to creating highlycrafted editions of new and old books. The spread of Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic Movement forms and ideas throughout Europe and the development of Art Nouveau, a full-blown style of its own, met with serious opprobrium back in Britain. In 1900, the Victoria and Albert Museum considered purchasing a few Art Nouveau works from the continent. Lewis F. Day said that the style “shows symptoms … of pronounced disease” and Walter Crane wrote using the terms “that strange decorative disease known as L’Art Nouveau.”6 A critic in The Magazine of Art wrote that “We explained that the main motive of the designs was a conscious striving after novelty and eccentricity, which is the basest of all motives in Art…and that there was throughout a fidgety, vulgar obtrusiveness quite destructive of all dignity and repose.”7 The sculptor George Frampton wrote, “I have nothing to say about l’Art Nouveau, as I do not exactly know what it means. I believe it is made on the Continent, and used by parents and others to frighten naughty children.”8 Though artists and critics on the continent did not feel as strongly about the differences between the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau styles,9 the Art Nouveau style was clearly a topic of some debate in Britain. The Art Nouveau style and its accompanying ideology was particularly abhorrent to the British public after the 1895 conviction of Oscar Wilde for “indecency”—as Wilde was a symbol of the decadent Aesthetic Movement and by proxy the Art Nouveau movement, scandal over his arrest at the end of the 19th century cast a pall over public opinion regarding Art Nouveau in general. 6 Pevsner, 90. Victor Arwas, Art Nouveau: From Macintosh to Liberty: The Birth of a Style (London: Andreas Papadakis Publisher, 2000), 12. 8 Ibid., 13. 9 Pevsner, 90-91. 7 Aubrey Beardsley, a British Aesthetic Movement and Art Nouveau artist, suffered a serious blow to his career because of his association with Oscar Wilde. As an artist who leaned very heavily toward the decadent in an atmosphere where many artists were concerned with creating utilitarian pieces in the name of social justice, he was somewhat isolated until Art Nouveau gained full force across Europe.10 Like the artists of the Art Nouveau movement, Beardsley embraced the use of new technology in creating his art, which consisted mainly of black and white ink drawings and illustrations. Many of Beardsley’s illustrations accompanied texts, one of the most famous of which is his suite of drawings for Wilde’s play Salome, published in 1894. However, after Wilde’s scandalous arrest, Beardsley ultimately converted to Catholicism, rejecting the erotic drawings he had created, and soon after died at the age of 25 in 1898. Beardsley’s story couldn’t be more different from that of William Morris, one of the founding theorists of the Arts and Crafts movement and an artist himself. Morris is best remembered as an artist for his designs and patterns for stained glass, textiles, and wallpaper, in addition to his work as the head of the Kelmscott Press, which he founded in 1891 to explore traditional book-making methods. For Morris, tradition was paramount—at the Kelmscott Press, he and his fellow artisans used 15th century production methods and typographic conventions. Though he and his followers created their own typefaces, they were based off of Renaissance-era precedents, in contrast to the typographical experimentation going on among the Art Nouveau poster and book makers on the continent. Morris’s art heavily reflects his religious underpinnings and the moralistic aspects of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Though Morris’s theory and work may not have influenced manufacturing practices as he’d hoped, his exploration of book-making 10 Escritt, 54. methods and styles inspired another generation of typographers and graphic designers whose work was to prove quite influential over the course of the 20th century and even today.11 Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo was a follower and acquaintance of both Ruskin and Morris, having studied under and then traveled with Ruskin in Italy and worked with Morris in the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.12 Like Morris, he believed in the importance of elevating the production of utilitarian objects to the level of fine art. The Century Guild, an artists collective he co-founded in 1882, is modeled after Ruskin’s and Morris’s views on the medieval-style guild of artisans. However, his title page for the 1883 book Wren’s City Churches is often considered the first example of Art Nouveau, and bears some stylistic similarity to Beardsley’s black and white ink drawings.13 Walter Crane, who spoke vigorously against the decadence of Art Nouveau, was, curiously, the first English Arts and Crafts artist to show works in Belgium, which is considered by many to be the birthplace of the Art Nouveau Movement in Europe.14 The son of a portrait artist, Crane came to illustration and bookmaking through apprenticeship rather than formal training at an art school. Despite Crane’s hatred of Art Nouveau’s decadent themes and distance from issues of social justice, his work contributed much to the development of the style. He was an early British admirer of Japanese prints,15 an important influence on Art Nouveau, and wrote a theoretical book on design entitled Line and Form, published in 1900, which spoke of “a kind of progression in the expressive possibilities of the line… the line of waves which lends expression to the strong upward spiral, the meander, the flowing line approaching the horizontal, 11 James Bettley, ed., The Art of the Book: From Medieval Manuscript to Graphic Novel (London: V&A Publications, 2001), 15. 12 Escritt, 39. 13 Pevsner, 81. 14 Escritt, 44. 15 Taylor, 66. or the sharp contrast and clash of right-angles”16—ideas about the forms of Art Nouveau very much in-keeping with the sometimes Symbolist language that those artists used. Though both the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts Movements may call to mind furniture and architecture, the bookmaking tradition was uniquely strong in England, and offers an opportunity to compare the works of those British artist and designers whose work helped influence the beginnings of the Art Nouveau movement, and whose ideology demonstrates the conflicts between Art Nouveau and the moralistic works that spawned it. Though both the Arts and Crafts Movement’s idealism and both movements’ naturalistic forms would soon be overtaken by the modern movement, just after the turn of the 20th century, the creative outpouring of the British graphic designers like Beardsley and the artists of Morris’ circle still influence graphic design and book production today. Images from Salome, by Aubrey Beardsley (1893-1894). Pen and ink. 23 by 16 cm. Now located at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Illuminated page of Canterbury Tales—“Wife of Bath,” by William Morris and Kelmscott Press (c. 1896). 11 by 16 ½ inches. Now located at the University of California, San Diego. Title page for Wren’s City Churches, by Mackmurdo (1883). Woodcut on handmade paper. 12 by 9 inches. Now located at the William Morris Gallery in London. Illustration from Flora’s Feast, by Walter Crane (1889). Hand-colored lithograph on card. 8 1/16 by 6 5/16 inches. Now located at the MFA in Boston. 16 From Crane’s Line and Form, quoted in Escritt, 45.