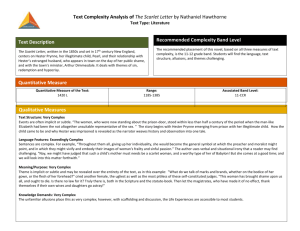

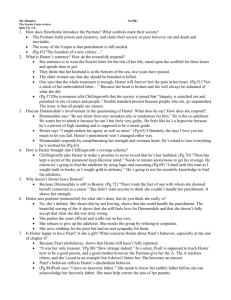

Study Guide The Scarlet Letter

advertisement