Final_Draft_Kingwood_Twp_Land_Use_Plan_Public_Hearing

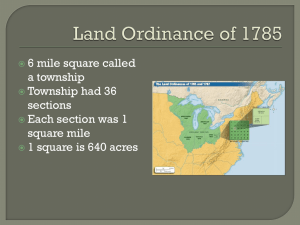

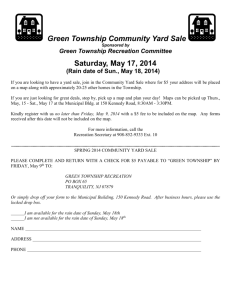

advertisement