BASELINE LUNG FUNCTION OF PATIENTS WITH ALLERGIC

advertisement

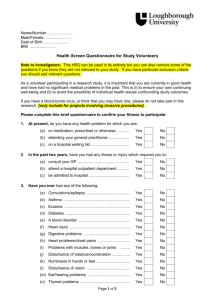

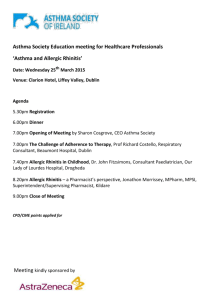

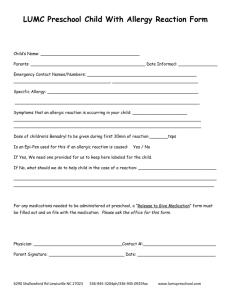

BASELINE LUNG FUNCTION OF PATIENTS WITH ALLERGIC RHINOSINUSITIS IN KANO. * A.Ajiya, * A.D Salisu, ** O.G.B Nwaorgu. * Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano, Nigeria & ** Department of Otorhinolaryngology, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan. Correspondence: Dr Abdulrazak Ajiya, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano, Nigeria. Email: ajiyaabdulrazak@yahoo.com. . Abstract Background: Allergic rhinosinusitis is a global health problem both economically and socially with significant impact on the quality of life of the afflicted. This is worsened when bronchial asthma, a comorbidity, is present. Aim/Objective: This study aimed to determine the baseline lung function status of patients with allergic rhinosinusitis. Methods: All adult patients seen in the Otolaryngology outpatient clinic of the study centre with clinically diagnosed allergic rhinosinusitis were prospectively entered in the study. The participants’ biodata, symptoms and signs were obtained using a specially designed interviewer administered questionnaire. The baseline lung function values of the patients were determined using spirometry as a measuring tool. The data were collated and analyzed using SPSS version 15 statistical software. Results: There were 300 patients, and 300 control participants. Sixty-one percent were females and 39% as males with a male:female of 1:1.6. The age ranged between 18-49 years (mean=29.3). Seventy percent had positive family history of allergy, while 19% were obese. Allergic rhinosinusitis was most common amongst students (38%). In the study group, the lung volumes were below 90%, and above 90% in the control group; which was statistically significant ( p=0.05). Older age group (odds ratio 13.0), female gender (odds ratio 10.9), and negative family history of allergy (odds ratio 7.7) were found to be associated with abnormal spirometry results in patients with allergic rhinosinusitis. Conclusion: There is impairment in baseline lung function of patients with allergic rhinosinusitis, even in the absence of asthma. Key words: Allergic rhinosinusitis, Bronchial Asthma, Co-morbidity, Lung function values Introduction Allergic rhino sinusitis constitutes a global health problem that causes major Illnesses and disabilities1. Both allergic rhinosinusitis and bronchial asthma are systemic inflammatory conditions that often coexist as confirmed by Annesi-Maesano in a cross-sectional epidemiological study which showed prevalence ranging above 40% in some countries2. According to the document “allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma” 2008 by Bousquet et al ; Allergic rhino sinusitis is clinically defined as a symptomatic disorder of the nose induced by an IgE-mediated inflammation following allergen exposure to the membrane lining of the nose1. Bronchial asthma is defined as a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many cells and cellular elements play a role in particular mast cells, eosinophils, T-cells, macrophages, neutrophils and epithelial cells3. Rhinosinusitis and bronchial asthma have been evaluated and treated as separate disorders, but recent advances in the understanding and knowledge of the underlying processes have moved current opinion towards the concept of unifying the management of these disorders. The “united airway disease hypothesis’’ proposes that upper and lower airway diseases are both manifestations of a single inflammatory process4. The prevalence of self reported allergic rhinosinusitis and its relationship with asthma among adult Nigerians showed that 31.8% of individuals with allergic rhinosinusitis have asthma; while 63.9% of those with asthma have allergic rhinosinusitis5 with several studies in Nigeria reporting high prevalence of both allergic rhino sinusitis and bronchial asthma. Few if any, reported on the baseline lung function status of patients with allergic rhino sinusitis. This study aimed to determine the baseline lung function status of patients with allergic rhinosinusitis in adult Nigerians. Participants and methods This study was a prospective, descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted on 300 consecutive eligible patients diagnosed clinically with allergic rhino-sinusitis at the ENT clinic of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital Kano that satisfied the inclusion criteria. This study was performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical review committee of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital. Informed consent was also obtained from each patient before recruitment. The study included consenting patients who presented with two or more of the following symptoms: nasal blockage/obstruction, excessive sneezing, excessive nasal itching and anterior/posterior watery nasal discharge. Excluded were patients with history of Sino-nasal tumours, nasal polyps, diagnosis of asthma, contraindication to spirometry or chronic chest disorder. An equal number of normal individuals matched in age and gender were recruited as control group. The control group included: medical students, nurses, medical doctors and other health workers. A specially designed form was used to record participants’ biodata and occupation while their symptoms were recorded using Lund’s symptom score protocol. Subsequently, each participant had spirometry (Vitalograph ALPHA, AL 015019, made in Ennis, Ireland) and the data analyzed using SPSS version 15 statistical software. Results Three hundred participants were recruited into the study group and another 300 matched for age and gender as a control group. There were 117 (39%) males and 183(61%) females with M:F ratio of 1:1.6. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 49years (29.3± 8.2 years). The majority of the participants are aged between 18 and 29years (58%), with fewer individuals (42%) in the older age group. Most of the participants (70%) in the study group had positive family history of atopy. Only 19% of the participants in the study group were obese. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study population. TABLE 1: GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY POPULATION (n=300). NUMBER OF PATIENTS PERCENTAGE (%) Age: 18-29yr 174 58 30-49yr 126 42 183 61 117 39 57 19 243 81 Family Hx of atopy: yes 210 70 No 90 30 Sex: female Male Obesity: obese not obese In the study population, allergic rhinosinusitis was most common in students (38%), followed by housewives (22.3%). Table 2 shows the distribution of occupation in the study population. TABLE 2: DISTRIBUTION OF OCCUPATION OF STUDY GROUP. OCCUPATION NUMBER OF PERCENTAGE PATIENTS (%) STUDENTS 114 38 HOUSEWIVES 67 22.3 CIVIL 30 10 89 29.7 SERVANTS OTHERS In both sexes, reduced lung volumes were more common in patients with allergic rhinosinusitis than in normal individuals. The difference in lung volumes were statistically significant between participants with allergic rhinosinusitis and normal individuals (p <0.05). Table three shows the spirometry test results for participants. TABLE 3: SPIROMETRY TEST RESULTS FOR PARTICIPANTS. Parameters NORMAL VALUES Study Group Control Group p-values 85.4(9.0) 93.8(9.6) <0.0001 89.5(12.7) 94.0(10.2) <0.0001 80.7(8.2) 92.2(8.8) <0.0001 86.3(11.8) 92.9(8.8) <0.0001 0.9(0.06) 0.9(0.1) 0.008 0.9(0.1) 0.9(0.1) 0.026 FeV1(%):Men Women 80% to 120% FVC(%):Men Women FeV1/FVC(L):Men Women 80% to 120% Within 5% of the predicted ratio DATA ARE EXPRESSED IN MEANS (SD). Tables 4 and 5 show that abnormal Spirometry results were associated with age 30years and above (odds ratio, 13.0), female gender (odds ratio, 10.9) and negative family history of allergy (odds ratio, 7.7); but obesity was found to decrease the risk of abnormal spirometry result (odds ratio, 0.5). TABLE 4: FACTORS AFFECTING SPIROMETRY RESULTS IN PATIENTS WITH ALLERGIC RHINOSINUSITIS. VARIABLE NORMAL ABNORMAL CHI-SQUARE p-value 72.0 <0.0001 SPIROMETRY SPIROMETRY AGE(yr): >30 99 27 <30 75 99 59 58 115 68 OBESITY :Obese 32 25 Not obese 142 101 FAMILY HX: Yes 109 25 No 65 101 SEX :Men 4.5 Women 0.03 0.1 0.75 72.0 <0.0001 TABLE 5: DETERMINANTS OF ABNORMAL SPIROMETRY RESULTS IN PATIENTS WITH ALLERGIC RHINOSINUSITIS PREDICTOR ODDS RATIO 95%CONFIDENCE p-VALUE INTERVAL AGE(yr): >30 13.0 <30 6.4-26.3 Referent(1.00) GENDER: Men <0.0001 Referent(1.00) Women 10.9 4.9-24.2 <0.0001 OBESITY :Obese 0.5 0.2-1.1 0.1 3.8-16.7 <0.0001 Not obese FAMILY HX: Yes No Referent(1.00) Referent (1.00) 7.7 Discussion The ISAAC report showed that in general, with some exceptions, higher levels of allergic rhinosinusitis are observed in communities with higher levels of asthma6. In this study, the majority of patients with allergic rhinosinusitis were females. This is consistent with several studies worldwide1,7,8,9, but in contrast with reports from some authors locally and internationally5,10,11. The higher prevalence in females is attributed to a greater cough reflex sensitivity of the female airway, the impact of hormones on the airway, and physiological differences between men and women in airway reactivity to allergens8. Fifty eight percent of patients with allergic rhinosinusitis are below the age of 30years. This is similar to findings by Desalu et al in Ilorin, North central Nigeria5. The result is also consistent with the observation that the disease is common in childhood, peaks in the early 20s, and then decreases1,8,12. A larger proportion of the allergic rhinosinusitis group have family history of allergic disease or atopy. This is similar to findings by Olusesi et al in Abuja , the Nigerian capital 9. Several studies on risk factors for allergic rhinosinusitis worldwide have shown that the strongest risk factor for the development of allergic symptoms has been a strong family history of allergic disease irrespective of the varying prevalence and environmental risk factors across populations and societies13,14. Obesity was not a common finding in the patients with allergic rhinosinusitis .This supports reports from studies in Nigeria5 and Japan15, where obesity was either not a risk factor for allergic rhinosinusitis or has negative associations with prevalence of allergic rhinosinusitis. Students were the most commonly affected by allergic rhinosinusitis in this study. This is in slight contrast to reports in Nigeria and Nepal9,10, but consistent with similar study done in Bangladesh16. Spirometry results in this study showed that reduced lung volumes were more commonly found in patients with allergic rhinosinusitis than in normal individuals. This is consistent with findings from a longitudinal study that there is a strong association between allergic rhinosinusitis and the onset of bronchial hyperreactivity in adults in the general population17. Determinants of abnormal spirometry results in this study were found to be age above 30 years, female gender, and negative family history of allergy. However, obesity was found to be protective against abnormal lung function test results. Cirillo and his colleagues reported gender not to be a significant risk factor for bronchial hyperreactivity in patients with allergic rhinosinusitis18, in contrast to the findings of this study. However, previous reports by Paoletti and his colleagues evidenced in support of findings of this study19. The findings of this study, however, should be considered in the context of the potential limitations of the study. Conclusion There is impairment of spirometry readings in patients with allergic rhinosinusitis, even in the absence of asthma. The management of allergic rhinosinusitis in our hospitals should involve a multidisciplinary approach involving the rhinologist, respiratory physician and ophthalmologist, such that patients will be followed up carefully to evaluate the possible onset of asthma. References 1) Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N, Aria Workshop Group; World Health Organization. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 108(suppl 5): S147-S334. 2) Annesi –Maesano I. Epidemiological evidence for the relationship between upper and lower airway disease. In: Relationship between upper and lower airway disease. Series Lung Biology in Health and Disease. Corren J, editor. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2003; 18: 105-128. 3) Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, et al. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J 2008; 31:143-78. 4) Togias A. Rhinitis and asthma: evidence for respiratory system integration. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111: 1171-84 5) Desalu OO, Salami AK, Iseh KR, Oluboyo PO. Prevalence of self reported allergic rhinitis and its relationship with asthma among adult Nigerians. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009; 19(6): 474-80. 6) Asher M, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CKW, Strachan DP, ISAAC phase three Study Group. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phase one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006; 368:733-743. 7) Klossek JM, Annesi-Maesano I, Pribil C, Didier A. National survey of allergic rhinitis in a French adult population based-sample. Presse Med. 2009; 38(9): 1220-9. 8) Gern JE, Busse WW. Contemporary diagnosis and management of allergic diseases and asthma. Pennsylvania, PA, Handbook in Health Care CO, 2007:81-96. 9) Olusesi AD, Said MA, Amodu EJ. A correlation of symptomatology with nasal smear eosinophilia in non-infectious chronic rhinitis. Preliminary report. Nigeria Journal of Clinical Practice. 2007; 10(3): 238-242. 10) Nepali R, Sigdel B, Baniya P. Symptomatology and allergen types in patients presenting with allergic rhinitis. Bangladesh J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012; 18(1): 30-35. 11) Lasisi AO, Lawal HO, Ogun GO et al. Correlation between eosinophilia and nasal features in allergic rhinosinusitis- A pilot study. Journal of Asthma and Allergy Educators. Dec. 2010; 1(6):219-222. 12) Lasisi AO, Abdullahi M. The inner ear in patients with nasal allergy. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008; 100(8): 903-5. 13) Maksimovic N, Tomic-Spiric V, Jankovic S et al. Risk factors of allergic rhinitis: a casecontrol study. Healthmed. 2010; 4:63-70. 14) Choi SH, Yoo Y, Yu J et al. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in young children with allergic rhinitis and its risk factors. Allergy. 2007; 62:1051-1056. 15) Kusunoki T, Morimoto T, Nishikomori R et al. Obesity and the prevalence of allergic diseases in schoolchildren. Paediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008; 19: 527-34. 16) Chowdhury MA, Rabbani SM, Yasmeen N, Malakar M. Allergic rhinitis: Present perspective. Bangladesh J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010; 16(1): 44-7. 17) Shaaban R, Zureik M, Soussan D, Anto Jm, Heinrich J, Janson C et al. Allergic rhinitis and onset of bronchial hyperresponsiveness: a population based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 176: 659-666. 18) Cirillo I, Pistorio A, Tosca M, Ciprandi G. Impact of allergic rhinitis on asthma: effects on bronchial hyperreactivity. Allergy. 2009; 64(3): 439-444. 19) Poaletti P, Carrozzi L, Viegi G, Modena P, Ballerin L, Di Pede F et al. Distribution of bronchial responsiveness in a general population: effect of sex, age, smoking, and level of pulmonary function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995; 151: 1770-7.