Statement of Jane Orient, M.D. - Association of American Physicians

advertisement

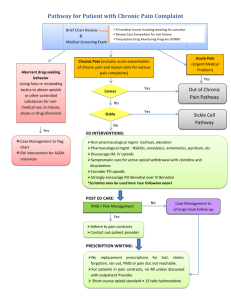

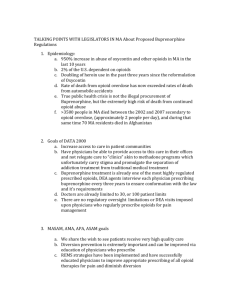

The Politics of Pain Management: Public Policy and Patient Access to Effective Pain Treatments B-338, Rayburn House Office Building December 16, 2003 Opioid Phobia and Physician Reluctance to Treat Pain Patients Jane M. Orient, M.D. Clinical Lecturer, Internal Medicine University of Arizona College of Medicine Executive Director Association of American Physicians and Surgeons I. A Recent History of Medical Teaching on Opioids Since I was a medical student in the 1970s at Columbia University in New York, opinion has changed dramatically about pain management, as well as many other things. The risk of drug addiction resulting from the prescription of opioids was considered to be very significant. It was better for patients to suffer pain, we thought, than to be turned into derelicts like those who frequented New York City emergency rooms with heroin overdoses. Post-operative pain was treated with low doses of “prn” intramuscular injections. Patients in pain had to wait for a nurse to answer the call button, wait to obtain the medication, and wait for it to take effect. If the medication was ineffective, there would be still more waiting as the nurse had to get a physician’s order to increase the dose. Many nurses were reluctant even to give the amount that was prescribed. Patients in pain wouldn’t take deep breaths, cough, or get out of bed. As a result, many got pneumonia and blood clots. Some of them died of inadequate pain control. Patient-controlled analgesia with intravenous morphine is now the standard of care for post-operative pain. Even with improvements in acute pain management, physicians were still reluctant to treat the intractable pain of terminal cancer with adequate doses of opioids. Better for patients to die in agony, it was thought, than to spend the last weeks or months of their lives enslaved to drug cravings. Some of them ended their agony, drug free, with a gunshot wound to the head. In the 1980s, it became widely accepted to treat the pain of dying patients with adequate doses of opioids. The availability of oral preparations of morphine such as MS Contin was a great advantage. Previously, most oral opioids were combined with aspirin or acetaminophen in an effort to enhance the effectiveness of low doses and to reduce the potential for abuse. It was impossible to ingest a large dose of codeine, hydrocodone, or oxycodone without at the same time receiving a toxic or fatal dose of aspirin or acetaminophen. Cancer patients receiving opioids in doses adequate to control pain (which might be very large) did not adopt the lifestyle of a drug addict, or spend their days in an opium fog. Tolerance to the depressant effects developed much more rapidly than tolerance to the analgesia. Until finally debilitated by their advancing cancer, the patients could be up and about, alert, enjoying normal social interactions and relative comfort. Patients with chronic “nonmalignant” pain, however, were usually denied opioids. They were referred to “multidisciplinary” pain clinics where they were supposed to learn to live with the pain. They were offered a variety of modalities: trigger point injections, hypnosis, biofeedback, nerve stimulators, physical therapy, nonsteroidal antiinflammatories, anticonvulsants, and “counseling”–anything but opioids. They underwent repetitive, expensive, frequently painful, usually fruitless diagnostic tests. All too often, they resorted to surgical procedures that, while indicated and effective for preventing nerve and spinal cord damage, frequently exacerbate pain. As the source of pain may be difficult or impossible to identify or treat, patients were often stigmatized as malingerers and “drug seekers.” Lack of success was attributed to “noncompliant” or “uncooperative” patients rather than to ineffective treatment. In the 1990s, the legitimacy of chronic pain in patients without cancer was increasingly recognized. Additional preparations became available in transdermal or sustained release form, such as Duragesic and Oxy-Contin. Such preparations have been a godsend to many chronic pain patients. Previously disabled, bedridden patients were able to resume a reasonably normal life and go back to work. They were not cured, however, and became dependent on drugs. The use of opioids for chronic pain is still often considered a last resort. The next logical step would be to treat pain early and aggressively in order to try to prevent the development of chronic pain syndromes with the accompanying depression, disability, and social dysfunction. However, we are instead seeing regression to an earlier era of demonizing opioids and the physicians who are willing to prescribe them. There are numerous continuing education programs for physicians in the proper, lawful, medically appropriate use of controlled substances for chronic pain, urging physicians to adopt a more enlightened view of the place of opioids and reassuring them that they need not fear licensure boards or prosecutors. Physicians no longer believe the reassurance. Even a single report of a physician who is delicensed or imprisoned for what other physicians view as good-faith prescribing not only chills but freezes the prescribing habits of thousands of others. And there are many such reports. Even if ultimately vindicated, a physician can be ruined by a mere accusation. Physicians–even pain specialists–are increasingly unwilling to prescribe chronic opioids, and desperate patients are being sentenced to lives of unremitting pain. II. The Problem of Drug Abuse and Diversion There is a lucrative black market for controlled substances, whether originating from a doctor’s prescription or from drug cartels. There is always a black market for things that people desire but cannot obtain by legal channels. As customers for addictive drugs may be desperate, enormous profits can be made by exploiting them. Professional “patients” are extremely skilled at deceiving physicians; there is, after all, no objective test for pain. The drug subculture in the United States is spreading to higher socioeconomic groups and younger age groups. It is not surprising that many substance abusers prefer prescription drugs. They are safer than street drugs, but can still be lethal, especially if misused There are many diverse opinions exist concerning the cause and solution to the social pathology of addiction. However, several points are clear: 1. Depriving pain patients of needed and beneficial prescriptions will not eliminate the drug subculture or reduce the number of twelve year olds who smoke marijuana or take Ecstasy at “raves.” 2. Reducing the number of prescriptions for controlled substances is likely to drive both addicts and pain patients to illicit sources and more dangerous drugs, so that mortality is likely to increase rather than decrease. 3. No physician is capable of unerring judgment. Chronic pain patients are difficult to treat at best, and legitimate patients are difficult to distinguish from skilled diverters or undercover agents who are zealously trying to entrap physicians. Moreover, even legitimate patients sometimes engage in illegal activities. 4. Physicians are being targeted with prosecutorial tools intended for drug kingpins. Every prescription they ever wrote can be a separate charge that they must defend. Conviction on any one of a huge number of charges can carry a draconian sentence under the mandatory minimum sentences. Physicians cannot be expected to risk loss of their livelihood much less many years in prison in order to write a prescription. 5. Drug diversion could often be stopped instantly by a telephone call to a physician’s office, notifying the doctor of a suspected problem and asking for cooperation. Law enforcement, however, appears to be more interested in obtaining physician convictions than stopping drug traffic. Physicians report that calls to law enforcement agencies about a suspected problem elicits neither interest nor action. In fact, physicians have been convicted on the basis of their own calls for assistance! III. Law-Enforcement Presumptions, Public Beliefs, and Medical Facts A number of misapprehensions fuel the campaign against doctors who prescribe high-dose opioids for chronic pain. These include: 2 A. If a patient dies while taking a physician’s prescription and has a blood level of that drug, the death is attributable to the prescription, and the physician may be charged with manslaughter or homicide. Facts: The last research on fatal doses of opioids were carried out in the 1920s. Monkeys intentionally given lethal overdoses of intravenous morphine required a dose equivalent to 500 mg in a 70-kg man. A study of morphine addicts showed that doses of nearly 2 gm (2,000 mg) caused insignificant changes in respiratory rate, pulse, or behavior. (1) Death is much more likely to result from a combination of drugs, especially including alcohol, than from an opioid alone. Moreover, if a drug intended for oral consumption is injected, the patient is also receiving the other contents of the pill. Examination of the optic fundi in patients who inject ground-up pills may show hemorrhages from talc embolization. (2) An embolus of insoluble particles or even air blocking blood supply to the brain could be the mechanism of death, rather than the drug. B. Opioids (“narcotics”) are peculiarly dangerous drugs. Facts: Opioids taken as directed, although they do cause dependence, are relatively safe by comparison with other drugs that may be used for pain relief, such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories. Used as directed, these drugs can cause cardiac arrhythmias, lupus-like syndromes, destruction of the bone marrow, fatal gastrointestinal hemorrhage, kidney failure, or other consequences. Overdose of acetaminophen (Tylenol) can destroy the liver. All medical treatments have potentially serious adverse effects; controlled substances are unique only in the threat of imprisonment to the doctor, even if the patient deliberately misused the drug. C. Extensive documentation and physical examinations are medically essential with every prescription of a controlled substance, and lack of same is evidence of criminal intent. Facts: The physical examination may be completely unrevealing as to the cause or magnitude of a patient’s pain. The most important information may be gleaned simply by observing the patient’s general appearance and gait, which are not necessarily noted in the medical record, especially if unchanged from previous visits. While “documentation” may be recommended as a strategy for physician self-defense, the number of words written in the chart bears no necessary relationship to the expertise of the physician or the validity of his judgment about the proper medication. IV. Conclusions: In summary, physicians have legitimate fears that good-faith prescribing of opioids could result in professional death and imprisonment because of factors outside their control; outdated and incorrect beliefs about opioids; ever changing, ill defined expectations about the required documentation and work-up of chronic pain patients, many of which are impractical and unaffordable for many legitimate patients. Unless fundamental changes are made, pain patients will suffer while substance abuse continues. The needs of patients, and the need of society to combat the social pathology of substance abuse, can be met only if physicians are treated by law enforcement as allies rather than adversaries, and the rights of both patients and physicians are respected. Zero tolerance for error will result in zero access to desperately needed treatment for many patients. References: (1) Weitzel RA. End-of-Life Pain Management: a Criminal Offense? J Am Phys Surg 2003;8:126-127. (2) Orient JM. Sapira’s Art and Science of Bedside Diagnosis, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Penn.: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. 3