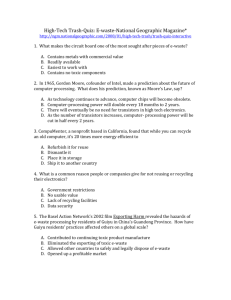

Computer waste can be a toxic mess

advertisement

Computer waste can be a toxic mess By Bill Lambrecht POST-DISPATCH WASHINGTON BUREAU CHIEF Saturday, Jun. 03 2006 ROLLA, MO. When a man with a truck offered to "recycle" a load of old computer monitors in 2001, the University City School District was happy to pay him $5 apiece to be rid of them. So district officials were distressed to learn that some of its equipment has turned up dumped in a once-idyllic place called Echo Valley amid stately cottonwoods and spring daisies. "When someone tells you they're going to dispose of them properly, you don't expect them to come back and haunt you years later," said Daphne Dorsey, spokeswoman for the district. The dump, on private land north of Rolla, was abandoned in 2003 by Elmer Dillard, a former electronics waste broker, according to court records and interviews. He lost the land after failing to make payments. Nearly three years later, the dump stands as a prime example of what can happen in the digital age with recycling only voluntary and few rules governing where computer junk and its hazardous components end up. "It's the poster child," said Robert Geller, director of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources hazardous-waste program. The department has been overseeing a slow cleanup - too slow to suit neighbors - that is being handled by another waste broker who had nothing to do with the mess. Meanwhile, computers that remain at Echo Valley tell a story of recycling ignorance and good intentions gone awry. Tags on monitors reveal computer owners as diverse as schools in Alton and Bethalto; Southern Illinois University; the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services; and the Missouri Botanical Garden, among others. Still more computer junk at Echo Valley came from the University of Texas, the Texas Department of Human Services and a school district in Irving, Texas, that trumpets a commitment to advanced technology. The institutions professed surprise - and a measure of embarrassment - about the resting place of their electronic junk. "That's not the way it's supposed to work. I feel like a pawn," said Rick Durbin, technology director for Alton schools. Charles Norwood handles computers for the Irving Independent School District in Texas, which boasts of having supplied 9,500 of its students with laptops. Norwood described a problem for computer users nearly everywhere: Seldom can people be sure where their old units are headed. "We get statements from recyclers saying they will dispose of them properly. But what they do with them, we don't know. Because all we have is a piece of paper," he said. Meanwhile, others bear the burden. "It was pretty here. Now it's an eyesore," said the Rev. Kerry High, pastor of the Macedonia Baptist Church, which overlooks the dump at Echo Valley. Race for solutions Federal law prohibits businesses from disposing of large quantities of e-waste in landfills. But in most states, including Missouri and Illinois, landfill-dumping by others is tolerated. Many people seek to donate old computer equipment, expecting it to be refurbished and reused or, at the very least, properly recycled. Sometimes they get their wishes. But by most accounts, only a small fraction of computers are properly recycled. Most are exported to Asia and Africa, which have few environmental safeguards for handling the hazardous properties of electronic garbage. With so much uncertainty, states and localities are struggling with what to do with tens of millions of computers, televisions and cell phones - commonly referred to as e-waste - that become obsolete every year. Their task is made more difficult, planners say, by the federal government's decision to support only voluntary solutions. Thus far, four states - California, Washington, Maine and Maryland - have enacted laws setting up funding mechanisms; six states have banned landfill dumping of e-waste. In Missouri, a group of recyclers and local planners, guided by the Department of Natural Resources, will meet next week in Jefferson City for the third time this year trying to carve out a compromise. For now, the so-called E-scrap Stakeholder Workgroup has ruled out proposing a landfill ban. In Illinois, a special commission last month recommended a landfill ban and a statewide recycling plan with manufacturers and consumers sharing the cost. Coming to grips with a burgeoning problem, planners have these concerns: Pollution. Lead in the monitors - 6 to 8 pounds of it - is just one of threats. E-waste also includes mercury and other unhealthful contaminants that might leach from landfills, studies have shown. Privacy. Retrieving personal information such as financial records and old e-mails from discarded computers that haven't been wiped clean is "child's play," as one expert put it. Exports. Computer equipment often is exported to China, Nigeria and places where labor costs make it more feasible for workers - sometimes children - to disassemble computers and to extract minute amounts of gold and copper. The Illinois commission reported last month that "unscrupulous recyclers export used equipment to some of the world's poorest countries. There, unprotected workers are exposed to toxic materials." Laura Yates, of the St. Louis County Health Department, heads the St. Louis Regional Partnership for Electronics Recovery, an alliance of local governments seeking to promote recycling. Participants are the city of St. Louis, and St. Louis, St. Charles and Jefferson counties. The regional network began accepting e-waste at 10 sites in February in hopes of keeping it out of landfills and away from countries ill-equipped to handle hazardous substances. Part of the aim, Yates said, is stimulating a thriving domestic market for the lead, plastics and precious metals removed from electronic equipment when disassembled. "Why are we sending all of our discards overseas so that someone else is burdened with them?" she asked. "We want them to go to legitimate, viable markets that don't involve 5-year-old children dipping circuit boards into buckets of acid." Nor does she want to see computers dumped in places like Echo Valley. 'He would just . . . dump them' Echo Valley is about 10 miles north of Rolla near Highway 63 in a swath of Ozark hills that once served as a horse farm. According to neighbors, the land was donated by the late Bernard Sarchet, an engineering management pioneer at the University of Missouri at Rolla, with the intention of establishing a Bible camp. Now, the land is strewn with computer monitors, piles of keyboards, plastic casings, broken glass and knots of wiring, as if a tornado had struck a computer warehouse. According to allegations in a civil suit filed in Phelps County, Elmer Dillard, of St. James, Mo., started bringing discarded computer gear to Echo Valley after purchasing the land in 2000. The original owners, John and Deborah Shook, who filed the suit, regained title to the land in a court ruling after Dillard failed to make payments. They were awarded a $4,000 court judgment - money they say Dillard never paid. "People would pay him to haul away their computers, and he would just take them out there and dump them," said John Shook, who estimated that more than 10,000 monitors were dumped, along with other electronic equipment. The Shooks later sold the land at what they calculated was a substantial loss. Dillard, who could not be reached for comment, has problems beyond his legacy of dumping: He was implicated in U.S. District Court in St. Louis last month in a scheme to defraud a state tax-credit program. A St. Louis County lawyer pleaded guilty to mail fraud in the case, in which Dillard allegedly permitted co-conspirators to use invoices from his Echo Valley company to cheat the Rebuilding Communities Tax Credit Program. An assistant U.S. attorney said in court that Dillard received "a kickback" for his efforts. He has not been charged. Missouri's Department of Natural Resources is permitting another company, Midwest Recycling, to operate in a warehouse at Echo Valley under an agreement that allows the company to bring in more electronic waste for recycling in return for cleaning up the property. John Roberts, 43, who operates Midwest, said that he has mixed tons of the dumped materials with newly arriving e-waste components when seeking out scrap yards and other buyers, some foreign. "There could have been a whole lot of trouble avoided if this stuff would have been recycled in the first place," he said. Michael Menneke, a hazardous waste specialist with the Department of Natural Resources, says Missouri has set no deadline for removing the hundreds of computers that remain. He said that the most potentially dangerous materials had been removed and that soil tests had showed no unhealthful lead levels. "What you saw out there was a tremendous mess, but only about one-tenth as bad as it was," he told a reporter who visited the site in April and May. Menneke said the state decided that it would have been fruitless to pursue other enforcement actions in the case. "This was the best solution for everybody, to get it cleaned up," he said. Computer tracking Institutions chafe at the thought of their e-waste ending up scattered in Missouri's rolling hills. "Clearly, we don't dump our computers," said Peggy Lents, spokeswoman for the Missouri Botanical Garden. The garden donates its old computers near and far, from St. Louis-area schools to the countries of Tanzania and Madagascar. She said the mid-1990s vintage monitor bearing the garden's identification that a reporter saw at Echo Valley had to be one donated by the garden long ago. In Illinois, equipment from the Department of Children and Family Services and Southern Illinois University are shipped, like all surplus state property, to the Department of Central Management Services in Springfield. As it stands, Central Management is required to seek a financial return to taxpayers, which means selling old computer equipment on the Internet or auctioning it to the highest bidder. But the agency's property control manager says Illinois is preparing to change its system soon by hiring a single company that sees to it that computers are wiped clean of sensitive data and properly recycled. "We want to do what's socially responsible and environmentally friendly," said Curtis Howard, property manager for the agency. Texas universities and departments send their computer equipment to the state's prison system for handling. University of Texas spokeswoman Marla Martinez noted that the prison system has changed at least one of its practices: Before selling old computers to brokers, tags identifying their origin are stripped. Meanwhile, even computer programmers like Randy Scott, who lives across the road from Echo Valley, wonder why Missouri hasn't been faster to respond. "It seems like they sure have been slow," he said. Added Tammy Snodgrass, of the Meramec Regional Planning Commission in St. James, "We have been working really hard in our region to deal with dumping and then someone does something like this." blambrecht@post-dispatch.com 202-298-6880