05. War in Ancient Greece

advertisement

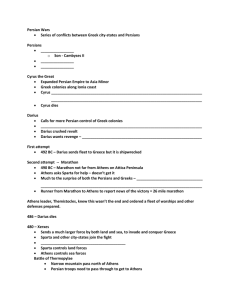

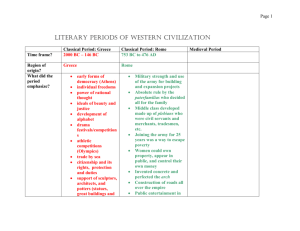

War in Ancient Greece The ancient history of Greece, when graphed with a line showing their culture’s achievements, resembles the Acropolis of which Athens was so proud. There was a slow ascent, a plateau reached in 500 B.C. that stretched nearly as far as 300 B.C. before a precipitous drop. The plateau is the time period of classical Greece, or more dramatically, the “Golden Age of Greece.” This period was one of the most productive in human history, and few disciplines of study exist that do not stem, at least in part, from thoughts Greeks had during their Golden Age. To scale the heights, Greeks fought in a war to preserve their freedom from the expansive Persian Empire. They won against all odds. The backside of the plateau, however, was also marked by a war, and the study of history was not born until Greeks began to reflect on their own weaknesses, on the brevity of life, and on the lasting importance of higher principles amidst the demise of their culture. The second great war of classical Greek history was a terrible internal struggle that ruined Greece’s potential as an independent civilization. In their pride and selfishness, the Greeks stumbled toward dissolution and absorption. The first war was the Persian War, and the second was the Peloponnesian War. Everything the Persian War was, the shameful Peloponnesian War was not. As you have seen in studying Athens and Sparta, war played a central role in Greek civilization. Young men participated in the athletics for which ancient Greece is famous not for fun but to train for war. The Persian War is the most glorious of all the Greek wars, and their success was also a springboard for all of Western civilization in that much of Greek culture is our culture. Were they destroyed, our future might have been swallowed up in the East forever. The story of the Persian War opened ingloriously, though, with Athenian diplomats committing a faux pas against the Emperor of Persia, the acknowledged master of the world. Athens was prospering under the leadership of Cleisthenes, but rival Sparta had interfered in Athenian politics in the instability prior to Cleisthenes’s political reforms, and Athens was afraid that the Spartans would come back. So, the Athenians dispatched emissaries to Darius I. As you have seen, Darius had made Persia the richest, largest, most powerful empire ever. The Athenians, in contrast, were a small group of frogs of the slightly larger group of frogs around a pond. When the Athenians arrived with their request for help in Sardis, a western capital of the Persian Empire, the Persian representative said, “But who in the world are you, and where do you live?” Persia had never even heard of the citystate of Athens. The Athenians persevered, however, because Athens had just humiliated the Spartans, and possibly the worst kind of enemy to have is a Spartan you have just humiliated. Athens wanted protection. Now, the faux pas. The Athenian ambassadors agreed to give Darius tribute by offering him dirt and water. Ignorant of Persian diplomacy, they thought they were merely striking a bargain in some kind of weird ceremony. They didn’t inquire too hard because they were desperate to take some evidence of success back to Athens. The gesture, however, really meant that Athens was so poor and lowly compared to Darius that mud was the best gift they could afford to give him. When the true meaning became known in Athens, Athenians were outraged, but they thought the bargain for protection against the Spartans had been struck. Darius merely thought that the Athenians were now his servants. This misunderstanding is the reason Persian leaders underestimated the Greeks. When a clash erupted between Persia and Athens, the “superior” Persians dispatched an army to annihilate “inferior” Athens. The truth is Persia was superior. They were obviously larger with more material resources, more people, more soldiers, and more wealth. The Persian Empire extended from modern Turkey to Afghanistan to Russia to Egypt to India. They were unified by tolerance and strong economic ties. In a war, Greece would be doomed. The one thing the Greeks had going for them in a conflict was that they possessed far better warriors. But when Darius got mad at Athens, could Athens stand alone? Of course not. Could Athens get Greece, including their rivals the Spartans, to unite against Darius? Unlikely. Could Greece defeat Darius? No way. Darius dressed in the finest, most expensive purple robes. He walked on red carpets his servants carried around for him on which no one else was allowed to walk. His subjects had to cover their mouths while Darius passed by so he wouldn’t have to breathe the same air. He had himself sculpted larger than life. He fed 15,000 friends and officials every day just to show off. How did Athens find themselves in conflict with this man? Greek civilization bordered the Persian Empire in Asia Minor in an area known as Ionia. Greeks had settled colonies there which had been absorbed by the Persians. The Persian Empire allowed subject peoples to live their own way as long as they paid their taxes. Independentminded Greek colonists, however, rejected the rule of the local Persian puppet tyrant in 499 B.C. in a revolt. They asked for aid from Athens. Athens joined with Eretria, another city-state, to punch Darius right in the nose. Athens, Eretria, and Ionia marched on Sardis and burned it to the ground. Darius was furious. The mud-tribute subservient Athenians had dared to help a revolt from his magnanimous rule! The Athenians wisely went home when the Persian army under general Mardonius came to crush the Ionians which he did by 494 B.C. In 490 B.C. Darius then filled 600 ships with 20,000 soldiers and 5,000 cavalry troops and sent them to Greece. First, they burned Eretria for its part in the Ionian revolt. Then the Persians took up a position on a plain near a swamp on the coast road to Athens. The Athenians were so intimidated by this force that they immediately dispatched a runner, Phiddipides, to ask the Spartans for help. Phiddipides ran 140 miles in two days from Athens to Sparta and back! Sparta wouldn’t come. Athens stood alone, therefore, at the Battle of Marathon. 9,600 Athenian hoplites lined up for battle against the 25,000 Persians, but the Athenians had a plan. As the battle lines drew near each other, the Athenians massed their soldiers on their flanks. The thin center line of soldiers did the unexpected when the Persian archers began to fire, they sprinted straight toward the Persian lines. This audacity stunned the Persians, but they quickly recovered and fought back against the Athenian center. They drove the attacking Greeks back, not knowing that these soldiers feigned a retreat. As the Persian army advanced into the breach, the Athenian flanks drove in from both sides. In the crush of this prearranged pincer movement, hundreds of Persians were immediately killed. The rest fled straight into the swamp where the Athenians pursued them, killing a total of 6,400 of the invaders with the loss of only 192 hoplites. The news of this glorious victory was the message that inspired the modern race known as the marathon. Erstwhile Phiddipides, barely recovered from the 140-mile run, ran ahead to Athens with the news that the Persians had been driven back into their ships or killed. The distance from Marathon to Athens is a bit over 20 miles, and upon completing his mission, Phiddipides dropped dead. While that was an incredible feat, a little-known yet amazing fact is that the entire Athenian army also ran back to Athens after having fought the Persians all day. They were afraid the Persians were going to sail around and sack the city, but the Persians just sailed away in dismay. The greatest honor these Athenian men could claim for the rest of their lives was that they had been Marathon fighters. Darius fumed. In 486 B.C. he began building up an army of annihilation. By 480 B.C., he was ready to move out. The invasion force was so great that it took seven days and seven nights just to cross the Hellespont. But the revenge of Darius would outlive him, because he died before the attack could commence. Xerxes, his son, carried on the overland invasion. Amazingly, however, thirty-one Greek city states united to repel this invasion of their homeland. Athens organized political coordination while Sparta saw to the military preparations. The opening of this confrontation is the famous Battle of Thermopylae, the Greek words for “warm gates.” Consider the odds. 130,000 foot soldiers and 20,000 cavalry made up the Persian army. This time, the Spartans were in on the glory. The Spartan king, Leonidas, personally led his 300 warriors to spearhead the assembled Greek army of 7,000 men. This tiny force had to hold the narrow mountain pass so that the rest of Greece could prepare for invasion. It is well that Spartan mothers admonished their sons to come back from the battle “either with your shield or on it.” Xerxes was flabbergasted when the Greeks did not simply flee. A Persian scout even reported that the Spartans were casually standing in front of their fortifications combing their long hair. This bizarre behavior was a Spartan custom before battle, but Xerxes merely interpreted it as defiance. Herodotus wrote that when one Spartan warrior heard that the Persian archers were so numerous that their arrows darkened the sky in battle, he said, “That’s good news. We will get to fight in the shade!” Persia’s superior numbers were no help, though—because of the narrowness of the pass--until a local Greek seeking a reward from Xerxes showed him a route to circle behind the Greeks. When betrayed, about 1,000 Greeks refused to retreat. Among these were Leonidas and his 300 Spartans, and they were killed to a man. This glorious stand at Thermopylae, however, gave Athens three days to retreat to the island of Salamis. A naval battle ensued which the Athenian navy miraculously won. Incensed, Xerxes ordered the abandoned city of Athens to be destroyed. Abashed at the loss of his fleet, he agreed to let Athens rule Greece for him. On their part, the Athenians resolved to rebuild their city better than before, and by 479 B.C. they refused to serve Xerxes. Xerxes returned to destroy Athens, again. The Athenians evacuated again, and the city was destroyed, again. Really mad, now, Xerxes underestimated what united Greeks could do, again. The Battle of Plataea was fought in 479 B.C. with 110,500 Greeks from all their allies standing against 148,000 invaders. Nearly half of the Persians were killed including Mardonius, the Persian commander. Only 3,000 Greeks were killed. The Greeks held a sixty-year party in celebration. These fathers of Western civilization had maintained their independence and ours. The elite Spartan and Athenian and other Greek hoplites had set in motion the Golden Age of Greece. Why would a civilization with such potential willfully wreck their future? That was the question Thucydides, the noted historian of the Peloponnesian War, tried to answer in inventing analytical history. Thucydides did not merely want to tell a sad story. He purposefully set out to explain what went wrong with Greek society. He collected data and then made a thesis just as you do when you write an essay in class. Thucydides likened the war to a Greek tragedy on the stage. The main character in a Greek tragedy exhibits a tragic flaw that only the audience can see. The drama comes from watching the tragic flaw lead the character inexorably to his fate. In his book The History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides identified Greece’s tragic flaw as hubris, a combination of selfishness and pride that manifests itself as destructive ambition. Thucydides explained how the desire of politicians for personal renown and the heightened rivalry of Athens and Sparta led to a deliberate renouncing of justice and reason and ultimately to a destruction of the Golden Age of Greece. Thucydides revealed that the glory of the Persian War was motivated merely by the will to preserve liberty rather than by patriotism. Greek nationalism was unknown. Thirty-one city states collectively recognized that Persian wanted to crush them. They vowed to preserve their freedom, and many Greeks lost their lives or property winning. Athens and Sparta, however, concluded they could crush the other Greeks around them. They were filled with hubris after their parts in the astounding victory against the Persians. Competitive city-states filled with hubris do not a nation make. Instead, both wanted an empire of their own. First, the Athenian Empire began merely as a naval alliance to protect its members from the Persians. Member city-states provided ships and men to bolster defense beginning in 477 B. C. The Spartans founded the Peloponnesian League named after the southern peninsula of Greece where other city-states allied with Sparta in fear of Athens. The Athenians and their allies, on the other hand, named their alliance the Delian League because their funds were kept in a treasury at Delos, an island in the Aegean Sea with a temple dedicated to Apollo. Over time, the Athenians preferred cash as the standard tribute to belong to the Delian League. Athens shouldered the burden of the navy, increasing their power indefinitely. Their allies had to pay up. Thasos, an island city-state, tried to pull out of the Delian League in 465 B. C. The island was besieged by the Delian League until 463 B. C. When Thasos submitted, Athens pulled down its walls and forced it to pay enormous fines. After making an example of Thasos, Athens demanded the Delian League to increase their payments until $200 million in modern money was coming in annual tribute making the 30,000-40,000 Athenians rich. The Delian League alliance had become merely the Athenian Empire, all to “stave off a Persian invasion.” The Persians had somewhere in here stopped attacking, and when fifty years of peace had gone by and the Delian League began to ask if the alliance was necessary, Athens simply responded, “See, it works,” and kept collecting tributes. Sparta did not sit idly by. They set their sights on Tanagra, a Delian League citystate. The first clash between Athens and Sparta (and their Leagues) came when Sparta helped Tanagra revolt from the Delian League in 457 B. C., although full-scale war did not immediately break out. In the wake of this scare from Sparta, Pericles became the most influential Athenian leader. In a similar move to that of Cleisthenes in creating democracy in the first place, Pericles proposed using money from the Delian League to pay poor citizens to be in the Assembly. Pericles was rich and served without pay as did the other wealthy citizens, but he won the support of the common citizens with this proposal. His next move was to relocate the Delian League treasury to Athens “in fear of Persian retaliation” for a botched attack he had ordered on Persian Egypt. The Athenian Empire began here, if not before. Pericles used his popularity with the poor to have his chief rival ostracized and showed promise as a visionary leader. He solidified control over Delian League uprisings and worked out a peace treaty with Sparta by 445 B. C. This balance lasted until 431 B. C. when the important city-state of Corinth finally decided it should choose sides and join a League. Pericles assumed it would join the Delian League, but Sparta proposed that Corinth come to their League with the promise that if Pericles consented, they would maintain the peace. Pericles refused and took Corinth for Athens. His decision engulfed nearly all the Greek world in war for 27 years. Pericles spent much of the money coming into Athens on rebuilding the Acropolis that had been destroyed by the Persians and left as a memorial to the sacrifices of Athens in the Persian War. The greatest building atop the Acropolis was the Parthenon. Pericles paid $1 billion in modern money for the construction which used 20,000 tons of marble. This impressive structure was 230 feet by 100 feet with 17 massive columns on a side and 8 columns along the front and back. With accomplishments like this, Athens was stubbornly prideful. They would not compromise nor even negotiate with Sparta. Pericles merely dictated ultimatums. We observed during the Persian War that a humiliated Spartan would make a terrible enemy. The only worse enemy might be a Spartan to whom you have issued an ultimatum. The Peloponnesian War broke out in 431 B. C. because both Athens and Sparta wanted to control Greece. They both feared each other and both wanted freedom from interference in their own affairs. When Sparta attacked, Athenians from the hinterlands simply moved inside Athens’s walls. Spartans couldn’t breech the walls, but they did ravage and pillage the countryside for forty days at a time. Forty days was all they could afford to be away from the helots back home, however. Athens smugness backfired on them, though. The cramped conditions inside the walls and the lack of provision for the refugees led to an epidemic in 430 B. C. We don’t know what the plaque was, but we do know the symptoms. Victims suffered from vomiting, convulsions, painful sores, uncontrollable diarrhea, fever, and thirst so great that deranged people threw themselves in cisterns for relief. They drowned and polluted the water and spread the plague further. Pericles himself died of the plaque, and the Athenian population was decimated. The Athenian navy, however, remained strong. General Cleon of Athens conceived a plan to go by sea to attack Sparta from behind. The resulting battle was at Sphacteria in 425 B. C. To the complete frustration of the Spartans, Cleon’s forces captured alive 120 Spartans. Such a feat was never done before under any circumstances by anyone! The key was Cleon’s use of peltasts, soldiers who threw javelins and “bullets” from slings. Lead balls were hurled with such force that they penetrated the skin from over 100 yards away. We still have some of these, and clever Athenians had inscribed the word Dexa on the bullets. Roughly translated, dexa means, “Take that!” Here was a chance for peace. Sparta offered a favorable peace to Athens to get the prisoners back. Cleon’s hubris caused him to urge Athens to go for more, and Athens rejected the peace. Sparta responded in kind. A Spartan commander named Brasidas did something else that the Spartan military had never seen. He borrowed ships from Persia, filled them with Spartans, and attacked the Delian League city-state of Amphipolis hundreds of miles from Sparta in 424 B. C. Amphipolis supplied gold, silver, and timber for ships to Athens, and was supposed to be guarded by none other than Thucydides. For neglecting the defense of Amphipolis, Thucydides was ostracized and turned to a career in writing history. Cleon went in 422 B. C. to stop Brasidas. In their clash, both generals were killed. The Athenian general Nicias picked up the pieces and offered peace to Sparta in 421 B. C. While it held, this cessation of hostilities was known as the Peace of Nicias. Hubris reared its ugly head again, however, in the person of a rich, young, hot-headed Athenian named Alcibiades. He seized power with a three-point plan: Protect Athens, empower himself, and crush something—anything. He crushed the island city-state of Melos in 416 B. C. because it sent money to Sparta. Alcibiades killed all the men of Melos and sold the women and children into slavery. Thucydides’ account of the attack of Melos is called the “Melian Dialogue” and was used without changing a word to announce Adolf Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938. Alcibiades, like Hitler, wanted to crush something else. In 413 B. C. he sent the man of peace, General Nicias, to attack Syracuse on the island of Sicily because it was a Spartan ally. General Nicias and most of the Athenians who went were slaughtered, and the Athenian navy was destroyed. Alcibiades then got into trouble over the vandalism of some male statues in Athens as well as his scheme of fighting for just power and glory. Before Athens could ostracize him, however, he defected to Sparta! The Persians did come back. They moved to cut off grain from Athens in the Black Sea and along the Ionian coast. The Peloponnesian War had so debilitated Greece that the Persians saw their chance for revenge. In the crisis, democracy collapsed in Athens which fell under the control of an oligarchy of 400 men, but Athens didn’t quit. They rebuilt the navy lost at Syracuse and, incredibly, recalled Alcibiades as a last-ditch effort. The Athenian navy then clashed with the Spartan navy in 410 B. C. in a battle called Cyzicus. It was the last victory for Athens and the Delian League. The Spartan officer after Cyzicus sent back a terse message—“Ships lost. Commander dead. Men starving. Do not know what to do.” Then there arose an oxymoron named Lysander. He was a Spartan naval genius, and he won three major naval victories in a row from 405-404 B. C. This news was so shocking to Athens that the Athenian commanders were condemned to death in a mass trial. Alicbiades was finally ostracized. Lysander’s victorious Spartan navy blockaded Athens with his borrowed Persian ships. The very strength of which Athens had been so proud, its navy, was supplanted by a foreign navy on its doorstep. Athens surrendered to the Peloponnesian League in 404 B. C. Thirty Spartan tyrants were sent to keep both Corinth and Athens from starting a whole new power struggle. The pitiful ending to this murderous “civil war” is that an Athenian revolution deposed the thirty tyrants but was too weak to do anything more but write plays, all of them tragedies. Sparta, too, was weak after decades of strife. For fifty years it expended more of its resources vying for control of Greece with Thebes. A foreigner from Macedonia invaded from the North and the independent “glory that was Greece” ended in a whimper.