Israa Dorgham

advertisement

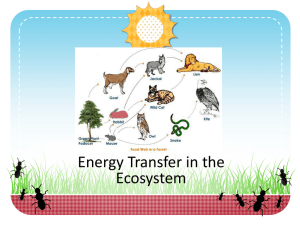

Israa Dorgham Biology 112 Dr. Robert K. Peet 18 November 2005 Hairston’s Impact on Ecological Understanding of Competition and Predation The paper published in 1960 entitled Community Structure, Population Control, and Competition by Nelson G. Hairston, Frederick E. Smith, and Lawrence B. Slobodkin has been hailed as a “classic” in terms of its impact on ideas regarding trophic cascades and by defining the elements that are most essential to community structure. Hairston et al. focus on the effects of factors such as fossil fuel accumulation, limiting resources, food supply, weather, predation, and competition on different trophic levels including decomposers, producers, and predators. The paper attempts to suggest which of these key factors plays a larger role in limiting population size. Hairston et al. base the paper on widely accepted observations in order to demonstrate a pattern of population control. The overall goal is to put down the disagreeing interpretations of the time that conflict regarding the idea of different trophic levels exhibiting different methods of population control. The first observation made is the accumulation of fossil fuels occurs at a rate that is slow and negligible compared to the rate of energy fixation through photosynthesis in the biosphere. This proves that decomposers, who are responsible for degrading organic matter, must be foodlimited; otherwise fossil fuel would accumulate rapidly which is not the case when considering the mentioned observation. The next couple of observations of terrestrial communities look at the obvious depletion of green plants by herbivores and the minimal mass destruction by meteorological catastrophes. As a result of these two observations, it is concluded that producers are neither catastrophe-limited nor herbivore-limited and must essentially be resource-limited. Generally, 2 the limiting resource for producers can be anything from light to water. Furthermore, the fact that herbivores can deplete vegetation whenever they become numerous enough when protected by man or natural events suggests that populations of herbivores are not limited by food supply. Another suggestion that has been proposed is that weather is a sufficient method for controlling herbivore populations. Hairston et al. refute this claim by explaining that hundreds of thousands of native forest species would have been able to escape from the ailments of weather through long, repeated exposure and also by selection. Therefore, weather cannot be a means of controlling herbivore populations. The final method of herbivory is predation. The paper suggests rigorous proof that herbivores are controlled by predation is lacking but some evidence has been collected. The conclusion here is that predators must limit their own resources to control herbivore populations, which defines predators as food-limited. By combining the mentioned observations and assumptions, Hairston et al. suggest that decomposers, producers, and predators of terrestrial communities are all resource-limited in a density-dependent fashion. Competition comes into the picture when there is more than one species existing in the same trophic level. Here competition can only be avoided if each species is limited by different factors. Since isolated cases of coexistence among an entire assemblage without evidence of competition for resources have never been described (except among herbivores), it is suggested that interspecific competition for resources exist among producers, carnivores, and decomposers. Hairston et al. argue that interspecific competition is a powerful selective force and is operating. The most obvious competitive mechanisms are found among decomposers, followed by producer species. According to Hairston et al., carnivores are the trophic level with the least common 3 interspecific competition mechanisms. Here Hairston et al. suggest a bottom-up control of trophic levels. The paper by Hairston et al. has generated much debate and controversy which has aided in making the publication an ecological classic. The first big wave of criticism was generated by Murdoch (1966) and P. R. Ehrlich and Birch (1967). The American Naturalist invited Hairston and his colleagues who wrote the original paper to reply to the criticisms which they did (Slobodkin 1967). The rebuttal to the criticism was longer than the controversial paper itself and specifically addressed the disapproval by other scientists. Murdoch’s first criticism is that the authors’ conclusions, if valid, would be of great significance but it is an incorrect attempt at generality. One of Murdoch’s specific criticism is regarding Hairston et al.’s referral to trophic levels “as a whole” when he suggests substituting the phrase with “in general.” Slobodkin et al. claim in their rebuttal that certain statements made in their original paper may not necessarily apply to every subset of populations within trophic levels such as herbivores and carnivores, but the statements made do adequately represent trophic levels as a whole. Another criticism presented regarding the classic paper was by Ehrlich and Birch (1967). Ehrlich and Birch deny that the complete consumption of organic debris by decomposers is sufficient evidence that decomposers as a group are food-limited, which a suggestion made by the 1960 paper by Hairston et al. According to Ehrlich and Birch, the meaning of food limitation implies that animals are “dying of starvation” which is not how Hairston et al. define it. This is explained in the rebuttal when Slobodkin et al. explain that in their 1960 paper, they suggest food limitation is equivalent to the population being proportionate to rate at which food is added to the community. They also add that asserting that population is food-limited does not deny the chance that a simultaneous limitation like predation can be acting on the system. 4 One major controversy the paper by Hairston et al. has incited is the debate on whether herbivores and carnivores can be considered alone without reference to other trophic levels. Ehrlich and Birch comment, “You could say that the cabbage white butterfly is food-limited because the world could be planted with more cabbages than it is, and if it were there would be more individuals of the butterfly around.” Ehrlich and Birch cite this example to show that here butterflies can be individualized from trophic levels. The response by Slobodkin et al. is that if this scenario plays out in real life by increasing the abundance of cabbage, the abundance of herbivores that are dependant on cabbage as a major dietary component would increase. Yet in order to increase the abundance of cabbage, it is necessary to decrease other species of plants and this would cause a decrease of the herbivores that depend on the displaced species. Increasing cabbage white butterflies by planting more cabbage would consequently decrease other plant species and decrease the predators of the missing plant species. Overall, the herbivore trophic level will not be seriously influenced, according to Slobodkin et al. Murdoch criticizes another aspect of the paper by suggesting that Hairston et al.’s observation that all vegetation is eatable is merely an assumption. Both Murdoch and Ehrlich and Birch note that many plants are adapted to be unpalatable, resistant, and inaccessible to some herbivores. Slobodkin et al. reply by challenging Murdoch to find any terrestrial community that consists of a dominant plant species that does not harbor an insect capable of defoliation or serious sap removal. Slobodkin et al. also add that many noxious insects derive their noxious property from eating plants that have not evolved unpalatable qualities. Many papers since 1960 have been generated in order to test and question the observations made by Hairston et al. In Morin and Lawler’s (1995) paper discussing food web structure, they give Hairston et al. credit for first developing the basic idea of trophic cascade. 5 They also mention that Hairston et al.’s classic paper predicts the particular tropic level that a species occupies will determine whether it is more likely to be regulated by competition or predation. Morin and Lawler build on Hairston et al.’s suggestions by commenting on the ways the food web theory can be tested. An experimental approach to suggestions made in the paper by Hairston et al. was performed by Vandermeer (1969) where he empirically tested the existence of higher order interactions carried out using ciliate protozoans. Vandermeer discusses the diverging empirical observation methods of the time in his work, suggesting that one idea is to emphasize underlying mathematical distributions and causes of deviance from these distributions which is a contribution made by Hairston et al. Nine years after the classic paper was published, Vandermeer discussed the “recent controversy” regarding Hairston et al.’s work in terms of their explanation for the structure of terrestrial communities, indicating the observations made by Hairston et al. were still being debated at the time. Today, there is current research being conducted that is still looking at the observations made in the 1960 classic, yet controversial paper published by Hairston et al. Van der Wal et al. (2000) discuss the hypothesis made by Hairston et al. that plant competition will be important at both low and high productivity because herbivore impact is low, which is the premise of their experiment on Triglochin maritima. The experiment looks at the effects of resource competition and herbivory on Triglochin maritima along a productivity gradient of vegetation biomass in a temperate salt marsh. It was found that although there is virtually no predation on the major herbivores, grazing pressure does not increase throughout the gradient, which was precisely predicted by Hairston et al. 6 The discussion of the roles of resource competition, herbivory, and predation in relation to ecosystem productivity still lives on today, forty five years following the publication of the paper by Hairston et al. Critics of the classic paper state too many generalities were made by Hairston et al. to be valid across varying species. Some suggestions to fill in the gaps of the paper published by Hairston et al. would be to look at the effects of herbivores that are seedeaters and nectar and pollen feeders since Hairston et al. only focused on herbivores that consume vegetation. Slobodkin et al. (1967) admit this was not adequately discussed in their original 1960 paper. Undoubtedly, the paper by Hairston et al. has caused many debates, inquiries, and experiments to test the observations concluded by the paper. 7 Literature Cited Ehrlich, P.R., and L.C. Birch. 1967. The “balance of nature” and “population control.” American Naturalist 101:97-107. Hairston, N.G., F.E. Smith, and L.B. Slobodkin. 1960. Community structure, population control, and competition. American Naturalist 94:421-425. Morin, P.J. and S.P. Lawler. 1995. Food web architecture and population dynamics: theory and empirical evidence. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 26:505-529. Murdoch, W.W. 1966. Community structure, population control, and competition – a critique. American Naturalist 100:219-226. Slobodkin, L.B., F. E. Smith, and N.G. Hairston. 1967. Regulation in terrestrial ecosystems, and the implied balance of nature. American Naturalist 101:421-425. Vandermeer, J.H. 1969. The competitive structure of communities: an experimental approach with proozoa. Ecology 50:362-371. Van der Wal, R., E. Martijn, A. Van Der Veen, and J. Bakker. 2000. Effects of resource competition and herbivory on plant performance along a natural productivity gradient. Journal of Ecology 88:317-330.