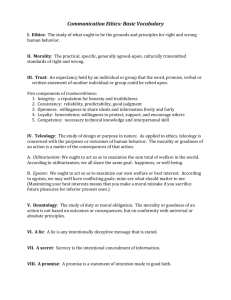

CHristian Utilitarianism - People at Creighton University

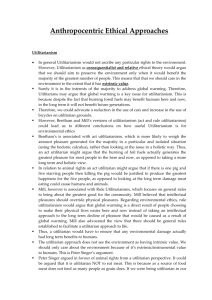

advertisement

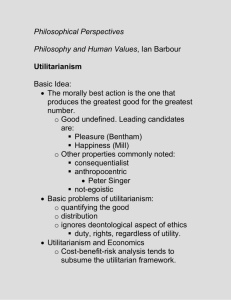

CHristian Utilitarianism "In 1768 Jeremy Bentham discovered the principle of utility, that the greatest happiness of the greatest number is the only proper measure of right and wrong and the only proper end of government." ((James Steintrage, Bentham, 11) I expect most philosophers know of Mill's claim that Utilitarianism is in compatible with Christian beliefs, since God wants the best for the greatest number. I also expect that most philosophers agree with Ryan who claims that "the attempt to pass Jesus off as a utilitarian is special pleading". Most tend to think that, as Richard T. DeGeorge claims, Christian ethics are fundamentally deontological. Utilitarians like Peter Singer seem to make claims quite contrary to Christian ways of thinking. Utilitarianism is an epistemological theory, not a metaphysical theory. It is a theory about how to identify the good, not a theory about what makes something good. We know the classic ethical dilemma from the Euthyphro which is taken up by divine command theorists and opponents is usually put as follows: is the good good because God says so, or does God say it is good because it is good? If the divine command theorists are right, and it is good because God says so, then God saying so is the metaphysical cause of its goodness. If the opponents of divine command theory are right, and God says it is good because it is good, then, while God's saying so is not a cause of the thing's goodness, since God is omniscient, we can at least use God's saying so as a great indicator of the good-- in other words, we might say that divine command theory could then be a good epistemological theory of the good-- a theory which helps us know what the good is, not necessarily why it is good. But utilitarians-- at least those who follow Mill, couldn't care less what the origin of the good is. Mill's utilitarianism is agnostic as to the origin or source of the actual value of goodness. Utilitarianism might be confusedly thought by some to be a metaphysical theory if one thinks that utilitarians claim that an act is good BECAUSE it brings about pleasure-in this case the pleasure-causing efficacy would be the causal factor or ground of the act's goodness. But Mill thinks that utilitarianism is an epistemological theory of morality-- it is a litmus test rather than a metatheory regarding the grounds of morality and goodness. Those who think ethics is always only about what makes the good good are right to think that Mill's theory does not meet their criteria of what constitutes an ethical theory. But then, that is unimportant because their criteria are mistaken. They mistake ethics for metaethics. Utilitarians, in their optimism, tend to think of the world as a place where whatever will bring about the most pleasure would be the best thing to do morally as well. This is the same seamless garment which natural law theorists and Aristotelians tend to bring to support. Happiness is ultimately connected to morality. The payoff of morality is happiness. This is of course contrary to Kant, who thinks instincts make us happy, and reason makes us moral (not happy). It is also contrary to Hobbes and Glaucon. If one holds to epistemological utilitarianism-- which is the only sensible utilitarianism to hold-- then it appears to be able to coexist quite well with a variety of positions. One could be a utilitarian divine command theorist, or a utilitarian natural law theorist or a utilitarian virtue theorist. But I am not interested in those points. I am primarily concerned to show that one could be a utilitarian Christian. In describing a Christian utilitarianism, I am not about to develop a list of Biblical values, or Church-provided rules. I don't want to do Christian Ethics ala James Gustafson or Stanley M. Hauerwas I am concerned to show that whatever we call Christian morality is compatible with utilitarianism, and secondly, to show that if we apply Plantinga's insights from his reformed epistemology to utilitarian ethical theory, we can begin to develop a Christian utilitarianism which is foundationless, but warranted, defendable, and rationally respectable. This also helps us to decipher the problem of the undecidability of criterion for utilitarians, and to address concerns of elitism, a basis for judgment, and proper pleasure distinctions. "Old Testament Morality, unlike Christian, is distinctly deontological. Moral injunctions like the Ten Commandments are thoroughly non-consequentialist in character: they are rules to be obeyed unquestioningly and without calculating the effect of obedience or disobedience in particular cases." (Scarre, UTILITARIANISM, 33) "its [Christianity's] conception of th ehappiness or well-being of mankind was ascetical and non-hedonistic . . . Man's greatest felicity is the beatific vision of God that is to be enjoyed after bodily death by those who have been saved (Anthony Quinton, Utilitarian Ethics, 12) "in its simplist5 and most rudimentary form bases the validity of th emoral principles it enjoins on the fact that they are commands of God" is also not utilitarian. (AQ, UE, 13) and "What constitutes moral goodness is obedience to GOd's commandments" so that one can achieve heaven. (Ryan, 1987, 22) Scarre points out that "QUinton's contention that JEsus could not have been a utilitarian since he did not maintain a hedonist theory of value holds water only if it is assumed that all utilitarians must be hedonists.: Act is good because it produces pleasure = Pleasure-production is what makes an act moral. Act is good if it produces pleasure, but not because it does. Pleasure-production is the means by which we can identify moral acts, but pleasureproduction is not what makes the act moral. Divine-Command theory utilitarianism makes perfect sense because divine command theory is a theory about what makes something right or wrong, while utilitarianism is a theory about identifying acts as right or wrong, not causing acts to be right or wrong. Basic Belief Utilitarianism In the end of the 20th century, a host of analytic philosophers helped us to see that the belief that the enlightenment project of gaining universally agreed upon truths was in doubt was not merely a French poststructuralist phenomenon. Whether Quine's claim that there is no analytic knowledge, Goodman's pointing out that we don't know what the criteria is for distinguishing good hypotheses from bad, Zagzebski's pointing out that knowledge seems to include a good deal of luck, or Plantinga's claim that many of our beliefs must simply be accepted as basic, and that various irreconcilable beliefs may be apparently basic from the point of view of different people, we have in an important sense lost the hope that we could provide a universal foundation, universally-acceptable principles, or an absolute guide for determining knowledge, truth, or gaining certainty. It seems unlikely that ethics is immune to this insight, so I suggest that we think through the Christian utilitarian ethics in this way. The question which is often put to the utilitarian is this: who will decide what brings the greater pleasure, who determines the higher from lower pleasures, and who is to calculate these pleasures? I suggest that the right answer to these questions is to say, as Plantinga (and apparently Calvin or Aquinas) would: the one who is properly functioning should do so. If you ask me what proper funcitoning is, I will describe it from my Christian perspective. Of course this is not simply everyone-for-themself anything-goes ethics. Because it is fallibile. I don't need justification for my view of what properly basic beliefs are about what is more and less pleasurable. But I do need to be prepared for defeaters. This view, that ethics is not based on justified foundations, is attractive to me not only because I am convinced by Plantinga, but because I am convinced as well by Levinas and to a lesser extent (and perhaps only insofar as he is influenced by Levinas) John Caputo. Caputo says in his book, "Against Ethics": "Obligation Happens" This seems to be very much in line with the anti-foundational approach of Plantinga. It is only right to be skeptical of this project and ask, "What, exactly, could count against your view of what is pleasurable?" How to Defeat Opponents to Christian Utilitarianism What then could I do to defeat other (non-Christian) views of what brings the greatest pleasure? There are a number of different methods. 1. Rortyan Reasoning. Even a Rortyan admits that we can still have rationality even if we don't know what Truth with a capital T means. I can still argue with you that your view is not as reasonable as mine, and I can attempt to convince you of my position. 2. Empirical Reasoning: I can try to provide empirical data which helps support my claim. For example, I might argue that cigarette smoking should be banned because of the negative consequences both to the individual and society in terms of money. 3. Levinasian Phenomenology/ Pascalian Romancing: I could describe the world in such a way that you begin to see things in the way that I do. Pascal tells the person convinced by his wager, who still cannot believe, to spend time with believers. Habituation of one's mindset is important. Of course this is especially important for reformed or pietist philosophers who believe that the heart and mind are intimately connected-- that proper functioning of the mind is tied to proper functioning of the heart, which is itself tied to proper habits. This is pure pietism, though it has elements of Aristotle, Calvin, and Jonathan Edwards in it. 4. Levinasian Encounter: I could simply put you in contact with the other. Perhaps if you argue that you have not obligation to help the poor, I could airdrop you into a refugee camp of desperate starving people in a third world country. If some of my students are discussing what sort of sports car their parents will buy them for graduation, and I bring my homeless friend Jim to come sit with them, this event makes their conversation seem out of place. It may make their concern even seem absurd. The hope of service learning projects seems to be to enable this sort of breakthrough encounter to take place, so that students begin to be haunted with the look of the face of the other. In less dramatic language, they will begin to have some moral imagination so that they think of others as well as themselves, and think about their own desires and wants in light of the needs and problems of others. In the language of Levinas, the other may become their meaning for being-- their checkpoint or guidepost in making decisions. So, if I had a Canadian atheist friend who was fond of saying "I am a happy person without God" perhaps I could go to his mansion with a group of poor homeless people and see if it would disturb his happy conscience. Perhaps I could go to him and continually ask him questions like, "how can you be happy when you are such a sinner?". This of course sounds absurd to many, because many do not at all understand what real love is. Many people are oblivious to the Nietzschean wisdom that a true friend tells you when you have faults. People often think that loving does not judge. Nietzsche knows better than to believe such nonsense.