Presentation by Richard Lynch, Ordette Wade and Marko

advertisement

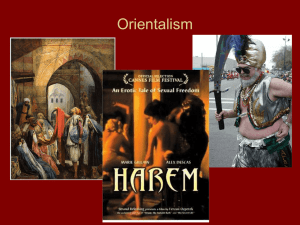

1 Seminar Presentation on Orientalism by Edward Said Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1979. (see excerpt, pp. 132-49 in Colonial Discourse and Post Colonial Theory ed. Laura Chrisman and Patrick Williams) Compiled by: Richard Lynch, Marko Scantlebury, and Ordette Wade Firstly, it is important to note that in his postulations on Orientalism Said did not set about to prove that Orientalism was some misrepresentation of an Oriental essence instead he shows that it operates with purpose, as all representations do. This purpose is according to some tendency within a historical, economical and intellectual setting. i The introduction of the book Orientalism begins with Edward Said defining key terms and the necessity of critically evaluating the definition of these terms and their interdependence. He speaks of the Orient in three lights saying it is “almost a European invention,... a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences” ( 1). He says that “in addition the Orient has helped to define Europe (or the West) as it’s contrasting, image, idea, personality, experience.” Said further clarifies that it is the place of “Europe’s greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its civilisations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other” (1). Said also sheds light on the term Orientalism. It is hugely important to bear in mind that here, by Orientalism, Said means “several things” all of which are “interdependent” (2). Providing for this interdependence are the fact that Orientalism “expresses and represents that part culturally and even ideologically as a mode of discourse with supporting institutions, vocabulary, scholarship, imagery, doctrines, even colonial bureaucracies and colonial styles,” while also being “A way of coming to terms with the Orient that is based on the Orients special place in European Western experience” (2). Said, a Palestinian American, begins by asserting that the Orient is not simply a fact of nature which just exists in the same way as the Occident is not really there. Said then alludes to Vico’s theory of the role of man in the creation of their histories. ii He continues to reinforce, whilst looking at the terms defined above and maintaining their interdependence; the various notions of, stating that the Orient “is not just there,” (4) though “it would be wrong to conclude that the Orient was essentially an idea” and such locales “ “Orient” and “Occident” are manmade.” In short, “Orientalism therefore is not an airy European fantasy about the Orient but a created body of theory and practice in which for many generations there has been a considerable material investment” (6). Having seen Orientalism as the study of all that is Orient and also the method of the origination of Orient via Orientalism then, “The relationship between occident and orient,” is posited by Said as “the relationship of power, of domination, of varying degrees of a complex hegemonyiii”(5). Said further qualifies that the structure of Orientalism should never be assumed to be “nothing more than a structure of lies or myths which, were the truth about them to be told, would simply blow away”(6). He writes, “After all, any system of ideas that can remain unchanged as teachable wisdom (in academics, books, congresses, universities, and foreign-service institutes) from the period of Ernest Renan iv in the late 1840s until the present in the United States must be something more formidable than a mere collection of lies” (6). Also, Said borrows from Gramsci’s theory of the distinctions which exist between the civil and political society (the former being constituted of voluntary affiliations such as schools and the latter with dominating state institutions such as the army). Culture, of course, is to be found operating within civil society, where the influence of ideas, institutions, and of other persons works not through domination but by what Gramsci calls consent in any society not totalitarian, then, certain cultural forms predominated over others, just as certain ideas are more influential than others; the form of this cultural leadership is what Gramsci has identified as hegemony. (7) Said posits that Europe constantly identifies itself as “against all those non-Europeans,” and argues that “the idea of European identity as superior to one in comparison...” (7) to any Others is precisely what makes European 2 culture hegemonic in and outside of Europe. Said contends that the “flexible positional superiority” allows the Westerner never to lose the “relative upper hand” during all possible relationships. Within the Western hegemony there emerged a complex orient suitable in nearly all disciplines as well as social and political display. Throughout the second section of his introduction his fears of distortion and inaccuracy are highlighted and how they can be reproduced “by too dogmatic a generality and too positivistic a localised focus” (8). Said then tries to deal with three aspects of his contemporary reality that according to him point out of the “methodological or perspective difficulties” mentioned above. The Distinction Between Pure and Political Knowledge It is in the third section of the introduction that Said clarifies and discusses the “three aspects of [his] contemporary reality,” (9) which have influenced the direction of his research and writing. One of which shall be discussed below. Within the aspect of “the distinction between pure and political knowledge” (9); Said depicts that although knowledge may appear to be non-political in nature it is problematic to make a clear separation between the two different spectrums of knowledge .i.e. (pure and political knowledge) No one has ever devised a method for detaching the scholar from the circumstances of life, from the fact of his involvement (conscious or unconscious) with a class, a set of beliefs, a social position, or from the mere activity of being a member of a society. These continue to bear on what he does professionally, even though naturally enough his research and its fruits do attempt to reach a level of relative freedom from the inhibitions and the restrictions of brute, everyday reality. (10) One can quite readily recognise that writers such as Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Keats and Mills produce works that consist of political implication. According to Said, Orientalism is an amalgamation of various fields of knowledge, whether intentionally or unintentionally, or whether it is overtly deemed political or non-political. Said states that Orientalism raises various political questions: What other sorts of intellectual, aesthetic, scholarly, and cultural energies went into the making of an imperialist tradition like the Orientalist one? How did philology, lexicography, […], novelwriting, and lyric poetry come to the service of Orientalism’s broadly imperialist view of the world? What changes, modulations, refinements, even revolutions take place within Orientalism? What is the meaning of originality, of continuity, of individuality, in this context? How does Orientalism transmit or reproduce itself from one epoch to another? “ (15) Said contends “Orientalism as a kind of human work” (15) and we should examine the relationship between knowledge and politics by implementing a study that addresses politics and culture .i.e. (humanistic study). He then further argues that each humanistic analysis must formulae that said connection in the specific context of the study, the subject matter, and its historical circumstances. Latent and Manifest Orientalism According to Said there was a “Fairly constant sense of confrontation felt by Westerners dealing with the East”(201). This confrontational resonance leads him to contend that a ““Science” like Orientalism in its academic form are less objectively true than we often like to think” (202). Everything mentioned prior to this segment of Orientalism was an attempt “ to describe the economy that makes Orientalism a coherent subject matter, even while allowing that as an idea, concept, or image the word Orient has a considerable and interesting cultural resonance in the West . In explicating this cultural resonance, Said maintains that we tend to believe in scholarly progression in that “scholarship move[s] forward” and “as time passes and as more information is accumulated, methods are refined, and later generations of scholars improve upon early ones” (202). He posits that “a great talent has a very healthy respect for what others have done before it and for what the field already contains” (202) suggesting that Orientalism is such a field where similar respect is paid to its established traditions calling them a “cumulative and corporate identity,” which is “strong given its associations with traditional learning” (202). The results he holds 3 with as much contempt as he holds the very hegemonic idea of Orientalism; since the Orientalists have granted for a consensus that certain representations are indeed correct. He then describes Orientalism as a type of “regularized (or Orientalized) writing, vision and study, dominated by imperatives, perspectives and ideological biases ostensibly suited to the Orient.” Said posits that there is a distinct way in which the Orient is taught, researched, administered and pronounced. Said draws our attention of Nietzsche who posits that the truth of language is combination of metaphor, metonyms and anthropomorphisms which after extensive use and reinforcement in a community, “become canonical and obligatory to a people.” (203) Said cites Nietzsche in his pursuit to inform of the truth of the ideology of Orientalism which goes beyond error and points towards political motivation with considerations of aspects of human nature arising from the study of the very ideology, positing that The orient was a word which later accrued to it a wide field of meanings, associations, and connotations, and that these did not necessarily refer to the real Orient but to the field surrounding the word. Thus Orientalism is not only a positive doctrine about the Orient that exists at any one time; in the West it is also an influential academic tradition (when one refers to an academic specialist who is called an Orientalist). (203) Additionally, he says of the term that it is to be viewed as an “area of concern defined” by a big enough range of people, “to whom the Orient is a specific kind of knowledge about specific places, peoples and civilizations.” (203) Within his critique Said suggests that idioms became frequent with the Orient as a trail of thought concerning the area whether it be the physical area or what one would believe the field of study to be (though these thoughts seldom corresponded with what the physical area was like) developed. He posits that beneath these idioms, “was a layer of doctrine about the Orient” which was fashioned by Europeans such that Orientalism became “a system of truths, truths in Nietzsche’s sense of the word v” (203). Said posits that human societies more often than not offer “imperialism, racism and ethnocentrism for dealing with “other cultures”, (204) giving rise to a contention that, “Orientalism is fundamentally a political doctrine willed over the Orient because the Orient was weaker than the West, which elided the Orient’s difference with its weakness” (204). Said progresses in his work to show that with the establishment of scholarship behind Orientalism coupled with the notion that such studies seemed indeed, “morally neutral and objectively valid,” Orientalism could in no way be challenged or revaluated. He postulates that “instead the work of various nineteenth-century scholars and of imaginative writers made this essential body of knowledge more clear, more detailed, more substantial- and more distinct from “Occidentalism”” (205). Quite grippingly he shows the irony of how the West, through its hegemonic nature, has sought to define the “other”; separate itself from the “other” though having enormous interest in a synergy of thought with the “other” which it is so determined to diminish in the face of perhaps underlying or innate political agenda. The distinctions between latent Orientalism and Manifest Orientalism become clear where the “almost unconscious (and certainly untouchable) positivity,” is latent while “the various stated views about Oriental society, languages, literatures, history, sociology, and so forth,” (206) is manifest Orientalism. For Said the former is stable, durable and is a constant, while the other derives from that constant and is consistently influenced by its very own ideology. He says of the writers he analyzed in chapter two: the differences in their ideas about the Orient can be characterized as exclusively manifest differences, differences in form and personal style, rarely in basic content. Every one of them kept intact the separateness of the Orient, its eccentricity, its backwardness, its silent indifference, its feminine penetrability, its supine malleability (206) He posits that Latent Orientalism is responsible for why these writers potentially “saw the Orient as a locale requiring Western attention, reconstruction, even redemption” (206). Following examples of the continuous representations of things Orient as requiring leadership and the inferiority of the people supported by the very 4 ideas of Binary oppositions Said contends that the Orient became subject to a “biological determinism and moral political admonishment” (207) leading to his point that “the very designation of something as Oriental involved an already pronounced and evaluative judgement” (207). Said then goes on to show how the latent Orientalism led to the perception and representation of the Orient men as inferior and uninterested in development and how this representation led to a viewing of the Orient with “Sexist blinders” (207) which made women, “usually the creatures of a male power fantasy.” i Said 273 The Edward Said Reader. ed. Moustafa Bayoumi and Andrew Rubin. New York: Vintage Books, 2000 iii The domination or predominant influence exercised by one nation (or state, region etc.) over others. iv French philosopher and writer known for his work on early Christianity and his political theories. v Nietzsche is quoted as saying: “What is the truth of language but a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms- in short, a sum of human relations, which have been enhanced, transposed, and embellished poetically and rhetorically, and which after long use seem firm, canonical, and obligatory to a people: truths are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are. ii