Unified English Braille (UEB) Implementation: State of the

advertisement

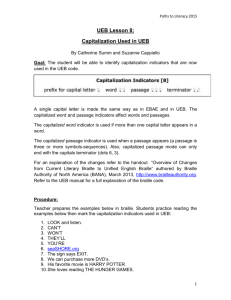

RNIB Centre for Accessible Information (CAI) Research report #14 Unified English Braille (UEB) Implementation: State of the Nations Published by: RNIB Centre for Accessible Information (CAI), 58-72 John Bright Street, Birmingham, B1 1BN, UK Commissioned by: Sarah Morley Wilkins, Principal Manager, RNIB Centre for Accessible Information Authors: Heather Cryer* – Research Officer Sarah Home – Accessible Information Development Officer Pete Osborne – Head of International Partnerships and Development * For correspondence Tel: 0121 665 4211 Email: heather.cryer@rnib.org.uk Date: 15 April 2011 Document reference: CAI-RR14 [04-2011] Sensitivity: Internal and full public access Copyright: RNIB 2011 © RNIB 2011 Citation guidance: Cryer, H., Home, S., and Osborne, P. (2011). Unified English Braille (UEB) Implementation: State of the Nations. RNIB Centre for Accessible Information, Birmingham: Research report #14. Acknowledgements: Thanks to all who contributed information and gave feedback on early drafts of this work. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 2 © RNIB 2011 Unified English Braille (UEB) adoption and implementation: State of the Nations report RNIB Centre for Accessible Information (CAI) Prepared by: Heather Cryer (Research Officer, CAI) Sarah Home (Accessible Information Development Officer, CAI) Pete Osborne (Head of International Partnerships and Development, RNIB) FINAL version 15 April 2011 Table of contents Executive Summary ................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ............................................................................ 5 2. About UEB ............................................................................. 5 3. The history of UEB ................................................................. 6 3.1 UK and UEB ..................................................................... 6 4. Potential issues with UEB ...................................................... 7 5. Potential benefits of switching to UEB.................................... 8 6. Research ............................................................................... 9 6.1 Opinions on UEB .............................................................. 9 6.2 Experiments with UEB .................................................... 13 6.3 Conclusions of research ................................................. 17 7. Key learning points .............................................................. 17 8. Discussion ........................................................................... 18 References .............................................................................. 21 Appendix 1: Learning from other countries .............................. 25 Appendix 2 UEB resources that have been developed ............ 34 Appendix 3 UEB adoption statements...................................... 35 CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 3 © RNIB 2011 Executive Summary The Unified English Braille code (UEB) has been in development for nearly twenty years, and the past decade has seen much activity in various countries preparing for, and implementing the code. This report aims to draw together knowledge and experience around UEB. The report covers the history of UEB, including potential benefits and concerns about the code. A literature review of existing research outlines findings on consumers' feelings about UEB as well as experimental research findings on the effects of UEB on braille reading and production. An outline is given of the activities of countries who have implemented UEB, demonstrating good practice in keeping stakeholders informed and gradually introducing the new code. Resources that have been developed relating to UEB are also listed, demonstrating the opportunities for sharing materials between countries using a common code. In summary, this report aims to give a comprehensive picture of what is known about UEB and its implementation around the world, to inform other countries who may be considering the code. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 4 © RNIB 2011 1. Introduction This report brings together knowledge and experience of Englishspeaking countries around the world that have a shared interest in unifying English braille. It is hoped that the information provided in this report will help to inform and shape the UK's Unified English Braille (UEB) development work. Important lessons can and should be learned from the experiences of the other countries that have already, or are currently implementing UEB. As UEB is the braille code that crosses international boundaries, any resources that have been developed could be shared, negating the need to develop country-specific rulebooks, training materials and resources. 2. About UEB UEB is a braille code designed for use in nearly all types of material including novels, poetry, recipe books, magazines, financial statements, computer manuals, instruction leaflets, scientific textbooks, mathematics and science. The representation of braille music is the one exception, as there is already a wellaccepted international code that has been widely adopted. The current braille codes used within English-speaking countries to represent literary braille are similar (though not identical) everywhere, and so substantial preservation of those codes was one of the original basic goals of UEB. Technical codes can vary greatly between countries and involve the user or producer understanding different braille representations that are dependent on the context of the material. Braille readers in any English-speaking countries who are already familiar with contracted (grade 2) literary braille will notice only small differences in UEB: No new contractions have been added Nine commonly-used contractions are no longer used ("ble", "com", "dd", "ation", "ally", "to", "into", "by" and "o'clock") CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 5 © RNIB 2011 Sequencing is not permitted (i.e. you cannot write "and", "for", "of", "the", "with", "to", "into", "by" and "a" directly next to the following word) All of the existing 180 contractions, wordsigns and short forms are unchanged (although there are some new restrictions on the use of some short form extensions) Ambiguity of braille signs has reportedly been eliminated, in that braille characters no longer have different meanings dependent on context. 3. The history of UEB In 1992, the Braille Authority of North America (BANA) began a project with the aim of creating one braille code which could be applied across all subject areas (with the exception of music which already has an internationally accepted braille code). In 1993, other English-speaking countries became interested in the Unified English Braille (UEB) project and it was internationalised under the auspices of the International Council on English Braille (ICEB). The goals of the project changed from developing a code for North America to developing a code for the entire English-speaking world, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Nigeria, South Africa, UK and the US. In early 2004 ICEB met and agreed that the UEB code was sufficiently complete for recognition as an international standard, which member countries could choose to adopt as their national braille code if they wished. ICEB recommended that UEB should be referred to the national braille authorities of member countries for consideration and possible adoption, after due consideration with their braille users and other stakeholders. 3.1 UK and UEB In July 2005 the Braille Authority of the United Kingdom (BAUK) decided that the UEB code was now sufficiently complete and stable enough to justify a major consultation of braille users in the UK. In 2008 BAUK developed, produced and widely distributed a UEB consultation pack, which included a number of samples in UEB and a questionnaire. The pack was sent out to over 4,000 braille users, producers, intermediaries and other stakeholders in the UK. 470 responses were received. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 6 © RNIB 2011 76% of respondents would not like to see UEB adopted as the standard braille code in the UK (24% would) 66% of respondents did not think that the adoption of UEB as the standard braille code in the UK would benefit future braille readers in the UK and worldwide (33% did, 1% didn't know). In the light of these results, BAUK came to the following conclusions at its meeting on 1 December 2008: BAUK does not recommend that UEB be introduced in the UK at this time. However, it recommends that the question be revisited in five years time (i.e. 2013) BAUK recommends that work be done to test the viability and usability of UEB for technical braille (e.g. maths, computing, science), in order to provide a basis of information in this area which can be input into future decisions on UEB. BAUK merged with two other organisations in January 2009 to form the UK Association for Accessible Formats (UKAAF). All braille-related work is now managed through the Braille Section of UKAAF. At UKAAF's AGM in 2010, a motion that "UEB be adopted as the preferred code to be implemented in the UK" was tabled. Discussions took place and concluded that the "AGM remit the motion back to the Board". In September 2010 the UKAAF Board formally approved that "Unified English Braille be permitted as an experimental code in the UK so that evaluation of the technical features of the code may take place." 4. Potential issues with UEB A number of areas have been identified as issues/sticking points with UEB by braille readers across the English-speaking countries: People simply don't like change Braille users are very protective of "their" braille code that they are familiar with (even though most of them are able to read legacy braille materials with old codes and materials from a number of different sources and do so without any problems) UEB is perceived as a code that was developed by technical experts to help braille producers rather than braille users Many braille users have only seen very early UEB samples and still remember the over-use of what they perceive as unimportant information and excessive coding (such as what CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 7 © RNIB 2011 font the original print document was produced in) - braille users don't forget! Numbering in UEB, although not an issue for current British Braille users who are already familiar with the numeral indicator and upper number signs (other countries use lower-case numbers and Nemeth is particularly prevalent in the US) Abolition of sequencing in UEB (being able to write "and", "for", "of", "the", "with", "to", "into", "by" and "a" directly next to the following word) Abolition of nine commonly-used contractions in UEB ("ble", "com", "dd", "ation", "ally", "to", "into", "by" and "o'clock") Increased size of documents in UEB - roughly 1 page per 50 pages for literary braille Perception that increased size of documents in UEB may slow down reading speeds Having to un-learn braille contractions to read UEB. 5. Potential benefits of switching to UEB There are many benefits that switching to UEB could bring to English-speaking countries. The following list has been drawn from the experiences of other countries who have implemented UEB or who are in the process of doing so: UEB has been well-researched and developed by braille experts over many years. The code is simpler to learn than British Braille, with no sequencing to remember and there are no new braille signs for existing readers to learn Unification of literary and technical codes means there is no need to learn additional codes for technical materials Ambiguity of braille signs is reportedly eliminated, meaning braille characters no longer mean different things in different contexts. This is a benefit for people learning braille and existing braille readers Harmonisation of numerous braille codes across Englishspeaking countries would bring the opportunity to share resources, saving time and cost in transcription and resulting in more braille material available to readers The greater opportunities for sharing material between countries who have implemented UEB is of particular benefit to developing countries who may not have budget to produce their own braille and rely on donations from a range of other countries CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 8 © RNIB 2011 The opportunity to develop and share resources internationally would mean less country-specific code development and maintenance costs. Braille teaching resources can also be shared across countries using the same code Countries can learn from each others' experience of implementing the code Translation software developments would benefit more producers Ability to accurately translate print-to-braille and braille-to-print, making it easier for print readers to translate braille accurately (for example, useful for sighted teachers marking braille work). 6. Research Over the years, various researchers have attempted to answer some of the questions raised about UEB through formal research. Some of this research has focussed on opinions and feelings about the code, giving insight into the barriers to adoption of UEB. Other research has been experimental, aiming to determine the effects of UEB on the size of documents and braille reading speeds. The following review of the literature aims to summarise research findings in these areas. 6.1 Opinions on UEB The views of braille users and practitioners have been sought throughout the development of UEB. Bogart and Koenig (2005) report key findings from the first international evaluation of the draft UEB code (carried out by the International Braille Research Center). This evaluation invited English-speaking braille readers, proofreaders, educators and transcribers from around the world to complete a questionnaire based on sample material produced in UEB. Respondents were asked to indicate their support for the general principles of UEB, proposed additions (such as capitalisation and print passage indicators) and proposed omissions of specific contractions. Overall, the majority of respondents supported the idea of a unified braille code (although in the UK, less than half - 37% - supported the idea). Support was generally high for additions such as capitals and print indicators, whereas there was more variation and generally less support for changes to spacing or omission of existing contractions. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 9 © RNIB 2011 Canadian research has explored students' and teachers' views on UEB through focus groups (Gerber and Smith, 2006). All participants were given an outline of UEB and samples of literary and technical materials in UEB to familiarise themselves with the code before the discussions. Respondents expressed a range of concerns about UEB, but also recognised some positive aspects of the code. Positive views on UEB raised by both teachers and students: the reduction in ambiguity of braille characters in different contexts the ability to share resources internationally UEB may be easier for new braille readers to learn specific features of the code including capitalisation, and changes to spacing (such as the abolition of sequencing). Positive aspects of UEB raised only by students: some students felt the technical element of the UEB code was an improvement on existing codes and may encourage more take-up of technical subjects among braille readers through not having to learn additional codes UEB may be easier for sighted teachers to teach, potentially improving integration in mainstream education inclusion of print indicators. Positive aspects of UEB raised only by teachers: one braille code for all materials (literary, maths, computing) UEB may be more straightforward to transcribe, potentially increasing availability of braille materials. Negative views on UEB raised by teachers and students: the complexity of the transition process to UEB the potential for UEB to make documents larger which could slow down reading and writing and increase the size and cost of documents the relevance of print indicators. Negative aspects of UEB raised only by students: the need to relearn a new code. Negative aspects of UEB raised only by teachers: CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 10 © RNIB 2011 how users would access older/historical material if they had never learned the old code that older braille readers or transcribers may feel it's not worth learning a new code and so give up on braille. The researchers noted that many responses from students who were braille readers were quite emotional and reflected the personal investment they had made in learning the existing braille code. Teachers were a little more removed, suggesting they would be willing to make the change so long as UEB was shown to benefit braille users. Overall, the researchers felt respondents' views on UEB were dependent on individuals' openness to change, experience with braille and familiarity with the rationale behind UEB. On this basis, they suggest that clearer communication about the purpose of UEB may improve people's perceptions. Further qualitative research explored potential implications of implementing UEB in America (Wetzel and Knowlton, 2006a). Focus groups were carried out with existing groups of transcribers, proofreaders, braille teachers and professional braille users. Respondents answered questions on the subject of implementation of UEB (specifically, what impact implementation would have on their work, how long it would take to learn the new code, how they felt the transition should be managed and so on). Overall, the consensus was that respondents would be willing to move to UEB if it would benefit braille users. Respondents highlighted that the effect of the change on literary braille would be minimal, although would have more impact on mathematics texts particularly, increasing their size. Key issues raised by braille users included the relevance of print indicators, which some respondents felt were a waste of space and did not add any useful information. Overall, braille users felt they would be able to master changes to the literary code within six months and changes to technical codes within a year. Key issues raised by braille transcribers included there still being some ambiguity in transcription to UEB, with some symbols still being context dependent. Other concerns included there being no back-translation package available yet and concern that aging CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 11 © RNIB 2011 volunteer transcribers may choose to give up rather than learn a new code. Key issues raised by braille teachers included that braille users complete work much more slowly than their print reading peers, therefore any further reduction in productivity (due to longer materials) would be undesirable. They also felt that any increase in the complexity of the code may reduce the number of braille readers. Another concern was that introducing a new code would make all existing braille materials obsolete, requiring huge resources of time and money to replace. Teachers felt they would need at least five years to become fully competent and comfortable with the new code, and that it would take a minimum of five years to prepare appropriate teaching materials. Overall, braille teachers felt the transition period would be huge, taking 20-40 years for full transition. These findings highlight that whilst overall respondents were open to UEB, there were many practical concerns, particularly in regard to the transition process. Another study investigated the views of professional users of technical braille codes in fields such as mathematics, science and computer science (Holbrook and MacCuspie, 2010). Before having any instruction in UEB, participants read high school texts on technical subjects. They then had a UEB tutorial, before reading documents from their own workplace in UEB. A focus group discussion followed. Overall, the technical users were very positive about UEB, as follows: The UEB code: makes sense regardless of context; represents technical information as well as other codes; may be better able to convey information spatially (important in technical subjects); is as easy to learn as existing braille codes, and without the extra effort needed to learn additional technical codes. UEB in education: less ambiguity of the code will help learners; ease of translation and back-translation aids integration in mainstream education and may enhance access to technical fields for braille readers; UEB would benefit students by giving them greater access to technical materials in braille; maths is easier in UEB, which may improve student and teacher confidence and interest in the subject CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 12 © RNIB 2011 Implementation of UEB: the competence and confidence of teachers with UEB should be investigated; need to justify the cost of implementation – to simplify the learning process is a good reason; whilst people can see the benefits they are resistant to change. In summary, technical users were open to UEB and even enjoyed the challenge of learning a new code. The positive attitude of these users is of interest as other research has suggested that technical users would be most affected by the changes. These findings suggest that despite the upheaval, technical users can see benefits to making the change. It must be noted however that this study used a very small sample of five technical users. It is hoped that this research will be replicated in the UK to gather further evidence. Overall, research findings into consumers' opinions and feelings about UEB demonstrate that changes to braille coding can be an emotional issue. Of key importance to many – end users and braille practitioners – is the effect UEB would have on braille users. In particular, there is concern about how the transition to a new code would work practically, and how this might affect braille readers currently in the education system. Despite these concerns, throughout the research, positive aspects to UEB were acknowledged, showing that despite some resistance to change, end users and practitioners can see benefits to the unification of the braille codes. 6.2 Experiments with UEB Experimental research into UEB has aimed to clarify the difference that UEB makes, to reading braille (such as reading speeds and accuracy) and to producing braille (such as size and cost of materials). Steinman, Kimbrough, Johnson and LeJeune (2004) investigated the reading rates and errors of experienced braille readers reading UEB. They filmed participants reading aloud their existing braille code (English Braille American Edition – EBAE), to measure reading time in seconds, miscues (such as additions/omissions or other mistakes) and regressions (stopping to go back). There was a one month break in which participants were given a UEB sampler and asked to familiarise themselves CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 13 © RNIB 2011 with the code. Then a second test session filmed them reading UEB aloud recording the same measurements. A significant difference was found in reading rates, with UEB being slower to read. Also, significantly more regressions (stopping to go back) were made when reading UEB. However, more miscues (errors) were made when reading EBAE. The researchers concluded that slower reading with UEB was likely to be due to unfamiliarity, as well as the slowing down due to increased regressions. This slow and careful approach with the new code may explain why fewer miscues were made with UEB than with the familiar EBAE code. Overall the researchers conclude that the changes in UEB are easily integrated (demonstrated by the fact that not all changes led to miscues). They believe that whilst initial learning of UEB may slow readers down, the code should not have a detrimental effect on reading braille in general. (Note: some limitations to this study include that it used a fairly small sample of eight respondents, and they did not control for how much respondents' practised with UEB between the two testing sessions). Further research into reading rates was carried out by Wetzel and Knowlton (2006b). They tested how a variety of changes proposed in UEB would affect reading rates in braille. For literary braille, they measured in turn the effects of spacing changes, removing whole word contractions, removing part word contractions and removing multiple part word contractions. Whilst additional spaces in UEB had no effect on reading rate (measured in cells per second), some significant effects were found when removing common contractions, showing that removing some contractions may slow reading rates. As this study tested effects of various changes in turn, the researchers suggest further research may be required to investigate the impact of multiple contraction removals within one passage. It must be noted that the participants in this study were experienced braille readers used to reading EBAE, therefore some of the slowing with removal of contractions could have been due to unfamiliarity. Overall, findings relating to the effects of UEB on reading rates and accuracy suggest that the change to a new code may initially have some effect on reading speed, as readers get used to the new code. However, further research may be required to determine CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 14 © RNIB 2011 whether the UEB code is slower for experienced braille readers to use once they are familiar with it. Experimental research has also considered the impact of UEB on producing braille. One area of concern has been the use of 'upper numbers' in UEB. Upper numbers depict numbers using the 'upper' part of the braille cell, matching the dot configurations of the letters a-j. Upper numbers are commonly used in literary braille codes. However, in technical codes (such as the Nemeth mathematics code), the lower part of the braille cell is commonly used for numbers, thus matching the dot configurations of various punctuation marks (comma, semi-colon, colon etc). As each system uses existing braille coding to denote numbers, each requires use of some indicators to make clear when numbers are/are not being used. For example, if upper numbers are followed by letters a-j, a letter indicator is required, whereas if lower numbers are followed by punctuation, a punctuation indicator is required. Research has investigated the occurrence of number/letter and number/punctuation combinations in literary and technical texts to explore the impact of the different numbering systems. Bogart, D'Andrea and Koenig (2004) studied samples of 16 textbooks (8429 pages in total) to identify instances of number/letter combinations and number/punctuation combinations. Findings showed that number/punctuation combinations were significantly more common. This means that when using lower numbers, punctuation indicators would be needed more often, increasing the size of materials. These findings support the use of upper numbers for all materials in UEB. Another study by Knowlton and Wetzel (2006) looked at the difference between UEB and existing American braille codes in terms of the space taken to produce the same materials. Their comparisons included literary braille (extracts from children's books in EBAE and UEB), mathematics (arithmetic and algebra samples in Nemeth code and UEB) and computing (two computer programs in Computer Braille Code and UEB). The measures of space taken included cell count, number of lines and number of line wraps (where an expression ran over more than one line). The effect of UEB on size of materials varied greatly depending on the type of material. For literary materials, UEB increased cell CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 15 © RNIB 2011 count by 4-7%, although there was no increase in number of lines. For computing materials, results varied with one text having fewer cells but more lines and the other having more cells but the same number of lines. For mathematical materials, again results varied. UEB rules allow transcribers to choose whether or not to include spaces around signs of operation. Where spaces were included, this increased the difference in size between UEB and Nemeth code. Size differences also varied depending on the type of mathematical material. Spatial arithmetic texts were longer in UEB (21.9% longer in UEB with spaces, 17.1% without spaces), whereas the effect on linear arithmetic was negligible (1.1% longer with spaces, <0.5% longer without spaces). Size of algebra texts was most affected by the change of code, being 46-54% longer in UEB with spaces and 20-35% longer without spaces. A key point to consider regarding the size of materials is the cost of production. Knowlton and Wetzel (2006) raise concern over an algebra textbook which at 25% longer in UEB than Nemeth code, had a corresponding 25% increase in production cost. An informal study carried out in the UK studied the effect UEB had on the size of different types of materials (Cryer and Home, 2008). For literary materials, comparisons were made between UEB and both capitalised and non-capitalised Standard English Braille (SEB) both of which are used in the UK. A greater difference was found between UEB and non-capitalised SEB (average increase in pages of 5.5%) than between UEB and capitalised SEB (average increase in pages of 1.97%). These findings suggest that the majority of increase in space taken by UEB is accounted for by capitalisation. Compared to capitalised SEB, UEB increased the number of pages by just 1 page in every 50 pages. For technical materials, results varied (between 4-12% increase in lines) depending on the complexity of the material and the amount of non-technical text included in the samples. In summary, the findings suggest that whilst for some materials the size difference of UEB is insignificant, there are cases – such as algebra – in which UEB significantly increases the size of documents. This may have implications for the cost of materials. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 16 © RNIB 2011 6.3 Conclusions of research Overall, research findings inform the UEB debate by offering evidence around some of the key issues. Whilst many consumers may be reluctant to make the change to UEB, it seems they can acknowledge some benefits of the code. Concerns around how UEB may affect reading are partially dispelled through findings that UEB changes are easily integrated and should not cause too many reading errors. However, for some materials the size increase of UEB may affect the material cost of production. 7. Key learning points The appendices of this report contain information on other countries' adoption/implementation of UEB (Appendix 1), resources developed for UEB (Appendix 2) and adoption statements from various countries (Appendix 3). Drawing on the experience of the countries who have already implemented UEB, there are a number of common themes which can be learned from. Exposure to UEB materials - such as sample documents in UEB - helps users to familiarise themselves with the code and understand the proposed changes (demonstrated by Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa) Informing stakeholders (braille readers, educators, and transcribers) about the proposed changes allows people to ask questions and become engaged in the process. This can be done through sharing information (such as Australia's 'UEB in a nutshell') or through engaging stakeholders in workshops and committees to discuss the issues around implementation (as in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Nigeria). Other specific approaches to stakeholder engagement include conducting research to identify stakeholders' concerns (as in Canada), offering training sessions to introduce the code (as in South Africa), and offering email lists for stakeholders to ask questions and discuss issues around UEB (as in Australia) Gradual implementation of UEB in education helps to minimise the impact on students who are trying to keep up with academic work whilst getting used to the new code. Many countries have taken a gradual approach, introducing new braille readers to UEB whilst continuing existing codes for older students (as in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa) CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 17 © RNIB 2011 Including symbols lists in UEB materials helps users as they become familiar with the changes (as in Australia, New Zealand, Nigeria). 8. Discussion Any changes to braille coding are an issue which can cause a lot of concern for both braille readers and professionals working with them. Research findings (discussed in section 6) demonstrate some of the emotions and concerns that the introduction of the UEB code has raised in various countries, and highlight that many people are – and may continue to be – resistant to such changes. Despite these feelings, a number of countries have successfully implemented the UEB code, and have reported benefits of doing so. Key benefits include: being able to work together with other countries and share resources; having less ambiguity in braille codes (making things easier for braille learners), and some reported increases in uptake of braille. The aim of this document has been to draw together information about UEB implementation from around the world, to inform decision making around UEB and to make it possible to learn from those who have gone before. Key learning points identified above from countries who have implemented UEB include: Giving stakeholders examples of UEB materials to become familiar with the code so that they are fully informed to understand the proposed changes Keeping stakeholders informed about UEB and the rationale behind it, and allowing them to ask questions and discuss any issues so that they can be involved in the decision process Implementing UEB gradually, particularly in educational settings to minimise disruption to students Providing 'cheat sheets' of new symbols for reference to help users become familiar with the code. The issue of giving people sample documents is particularly pertinent in the UK. Some UK braille readers who took part in early evaluations of the UEB code were put off by the many print passage indicators presented in sample UEB materials (some of which were later removed). This has led to some negative feeling CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 18 © RNIB 2011 towards UEB as being overly complicated and too print-orientated. Furthermore, when a UK consultation was run on UEB in 2008, sample documents provided included various technical materials which many literary braille readers may not usually come across. This further fuelled concerns about the complexity of the code. Anecdotal reports from other countries confirm that care needs to be taken over sample material provided, making sure that samples are relevant to users representing the type of information they would normally read. In order for UK braille readers to have a clearer idea of what UEB is like, it would be beneficial to produce more everyday sample documents. Keeping stakeholders informed about UEB is important. Research findings (Gerber and Smith, 2006) suggest that greater understanding of the rationale behind the changes may improve people's perceptions of UEB and their likely acceptance of it. Implementing UEB gradually is likely to be a necessity, particularly in education, in order to minimise disruption to those trying to keep up academically whilst taking on changes in the braille code. Countries who have already implemented UEB have successfully transitioned within 5 years (e.g. Australia). However, research findings suggest that some stakeholders feel it will take a whole generation to fully transition (20-40 years) (Wetzel and Knowlton, 2006a). The length of transition will be an important decision for countries yet to implement, as there are cost implications in terms of maintaining existing braille codes if the transition period is long. The continuing issue of maintaining braille codes is a key consideration for the remaining English-speaking countries who have not implemented UEB. A key benefit of UEB is shared resources and therefore shared costs, but if some countries choose not to adopt the code they will need to take on full responsibility for maintaining the braille code used in their country. As the number of countries adopting UEB grows, the change may gain momentum until it is more costly not to adopt than to do so. As a key purpose of UEB is unity between countries, the benefit of moving to UEB will be diluted for those who have adopted if other countries do not follow suit. Overall, there are many issues for countries to consider in their decision whether or not to adopt UEB. It is hoped that this paper CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 19 © RNIB 2011 will offer useful background information to those making such decisions. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 20 © RNIB 2011 References Blind SA Braille Committee (2010). Annual report by the braille committee for the year 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2010. [online] Available from https://www.givengain.com/cgibin/giga.cgi?cmd=cause_dir_news_item&news_id=94827&cause_i d=1137 accessed 21 February 2011 12:03 GMT. Bogart, D., D'Andrea, F.M., and Koenig, A. (2004). A comparison of the frequency of number/punctuation and number/letter combinations in literary and technical materials. Presented at ICEB General Assembly 2004, Toronto, Canada, March 29 – April 2, 2004. Bogart, D., and Koenig, A.J. (2005). Selected findings from the first international evaluation of the proposed Unified English Braille Code. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 99 (4), 233 – 238. Braille Authority of New Zealand (2005). Minutes of the 16th Annual General meeting of the Braille Authority of New Zealand. Braille Authority of New Zealand (2010). Braille Authority of New Zealand Country Report from New Zealand to Mid Term Meeting of Executive International Council on English Braille. Braille South Africa (2004) UEB in South Africa. [online] Available from http://www.ebility.com/roundtable/aba/ueb.php accessed 21 February 2011 11:23 GMT Canadian Braille Authority (not dated). The Unified English Braille Code: Background [online] Available from http://www.canadianbrailleauthority.ca/en/UEB.php accessed 18 February 2011 11:52 GMT. Cryer, H., and Home, S. (2008). Comparing Standard English Braille and Unified English Braille codes. RNIB Centre for Accessible Information, Birmingham: Research note #1. Gerber, E., and Smith, B.C. (2006). Literacy and controversy: Focus-group data from Canada on proposed changes to the braille code. Journal of Visual impairment and blindness, 100 (8), 459 – 470. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 21 © RNIB 2011 Holbrook, M.C., and MacCuspie, P.A. (2010). The Unified English Braille Code: Examination by science, mathematics and computer science technical expert braille readers. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 104 (9), 533 – 541. Howse, J., Gentle, F., Stobbs, K., and Reynolds, J. (2010). Transition to Unified Englsih Braille (UEB) in the ICEVI Pacific region. Presented at Think Globally, Act Locally conference of the Round Table on Information Access for People with Print Disabilities. 23-25 May 2010, Auckland, New Zealand. [online] Available from http://roundtable2010.wordpress.com/conferenceproceedings/7b-transition-to-unified-english-braille-ueb-in-the-icevipacific-region-by-josie-howse-frances-gentle-karen-stobbs-janetreynolds/ accessed 8 March 2011 14:27 GMT. Jolley, W. (2009a). Unified English Braille in Australia: the why, how and results. Presented at CNIB Braille Conference 'A braille Odyssey: 2009 and beyond'. Toronto, Canada, 29-30 October 2009. Jolley, W. (2009b). Braille today for tomorrow: joining the dots to cover the world. Keynote presentation at CNIB Braille Conference 'A braille Odyssey: 2009 and beyond'. Toronto, Canada, 29-30 October 2009. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness (2006). From the field: New Zealand adopts Unified English Braille Code. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 100 (1), 56. Knowlton, M. and Wetzel, R. (2006). Analysis of the length of braille texts in English Braille American Edition, the Nemeth Code, and Computer Braille Code versus the Unified English Braille Code. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 100 (5), 267 – 274 Lee, P. (2009). Interview with Peter Lee, Production facility team leader. [online] Available from http://bnobel.wordpress.com/ accessed 17 February 2011 14:22 GMT National Braille Council of Nigeria (NABRACON) (2005). The National Braille Council of Nigeria votes to accept the Unified English Braille Code (UEB) for future implementation in Nigeria. [online] Available from CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 22 © RNIB 2011 http://www.ebility.com/roundtable/aba/ueb.php accessed 21 February 2011 12:45 GMT Nobel, B. (2010). CBA Newsletter: Presidents Message. [online] Available from http://www.canadianbrailleauthority.ca/en/newsletter.php accessed 18 February 2011 13:55 GMT. Nobel, B., and MacCuspie, A. (2009). Implementation of Unified Englsih Braille (UEB) in Australia and New Zealand. AER Bulletin, Winter 2009. Round Table on Information Access for people with print disabilities (2010a). Unified English Braille: the rules of unified English braille. [online] Available from http://www.ebility.com/roundtable/aba/ueb.php accessed 18 February 2011 10:29 GMT. Round Table on Information Access for people with print disabilities (2010b). Australian Braille Authority: What we do. [online] Available from http://www.ebility.com/roundtable/aba/ accessed 18 February 2011 10:33 GMT Round Table on Information Access for people with print disabilities (2010c). Publications and activities: Ozbrl listserve [online] Available from http://www.ebility.com/roundtable/aba/publications.php accessed 18 February 2011 10:57 GMT Shanaghan, M. (2009). Interview with Marg Shanaghan, adult braille reader. [online] Available from http://bnobel.wordpress.com/ accessed 17 February 2011 14:29 GMT. Steinman, B.A., Kimbrough, B.T., Johnson, F., and LeJeune, B.J. (2004). Transferring Standard English Braille Skills to the Unified English Braille Code: a pilot study. Re:view, 36 (3), 103 – 111. Wetzel, R., and Knowlton, M. (2006a). Focus group research on the implications of adopting the Unified English braille code. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 100 (4), 203 – 211. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 23 © RNIB 2011 Wetzel, R., and Knowlton, M. (2006b). Studies of braille reading rates and implications for the Unified English Braille code. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 100 (5) 275 – 284. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 24 © RNIB 2011 Appendix 1: Learning from other countries The following English-speaking countries have been involved in the development of UEB: Australia Canada New Zealand Nigeria South Africa UK USA Of these, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Nigeria and South Africa have adopted UEB, and are in various stages of implementing the code. Australia were early adopters of UEB and have now completed their implementation. For this reason, a great deal more information is available from Australia than the other countries involved in the project. The following sections outline UEB activity in the individual countries. 1. Australia Key organisations Round table on information access for people with print disabilities: Committee of organisations aiming to improve accessible format provision across Australia Australian Braille Authority: A sub-committee of the Round table, which oversees development and maintenance of braille codes in Australia Vision Australia: The largest non governmental braille producer in Australia. Braille usage Exact figures unknown – thought to be in the low thousands for braille reading adults with some hundreds of students learning braille (Jolley, 2009a). Timeline From Jolley (2009a); Howse, Gentle, Stobbs and Reynolds (2010); Round Table on Information Access for people with print disabilities (2010a; 2010b) 1984: Having previously used British Braille, Australia adopt the use of capital indicators and use a hybrid system of British and CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 25 © RNIB 2011 US codes. This proves difficult to keep up-to-date and costly to provide training materials 1995: The Australian Braille Authority (ABA) receive government funding to run UEB workshops. This gives Australian braille readers an early introduction to UEB, allowing them opportunity to input into development 1998: Australian braille readers take part in the ICEB evaluation of UEB 2000: The Australian braille community are ready for a change with their options being to adopt either UK codes, US code or UEB, or to continue with a hybrid approach either with or without the Australian variations April 2004: ICEB decide that UEB is sufficiently complete to be considered for adoption May 2004: ABA decide they will adopt UEB the following year. In the meantime, they produce sample documents in UEB to both familiarise stakeholders with the code and to request feedback. An action plan is developed to take account of the needs of key groups affected by transition, such as students May 2005: UEB adopted as the national standard for braille in Australia. Members of the ABA are encouraged to implement UEB within five years. Five year transition period agreed to enable people to learn the new code. 2006: State based government education agencies begin production of UEB for educational materials May 2006: Unified English Braille Primer: Australian Edition is published, the first UEB reference/training document July 2006: Vision Australia start full scale production of UEB for all types of braille material (though other codes are still produced on a case by case basis) June 2010: UEB Rulebook published by the Round Table on Information Access for People with Print Disabilities: 'The Rules of Unified English Braille'. 2010: Successful transition to UEB complete. Implementation process Education: For new braille learners (kindergarten to year 2) all new and existing materials were produced in UEB to avoid any confusion in exposure to old coding. New literary materials for kindergarten to year 11 were produced in UEB as well as new and existing mathematics for kindergarten to year 6. Final year students were not switched to UEB to avoid disruption to their CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 26 © RNIB 2011 examinations (Howse et al, 2010). It was left to teachers' discretion as to when students should move to UEB, with some pupils in higher grades being given UEB materials with a key to the code. Many students chose to make the move to UEB having had a few texts using the code (Nobel and MacCuspie, 2009) Adult braille readers: Community workshops and information sessions were held in public libraries to inform people about UEB and give them opportunity to learn the code. From 2006, the national braille library started to produce all new materials in UEB (although stock in previous codes was still available to borrow) (Nobel and MacCuspie, 2009). Library books were provided with a list of UEB symbols in the font for reference (Shanaghan, 2009). An email discussion list was set up to give people the opportunity to ask questions and discuss issues around UEB (Round Table on Information Access for people with print disabilities, 2010c) Transcribers: Formal training was given to transcribers using the Australian UEB primer (Nobel and MacCuspie, 2009). Most transcribers picked up the changes quickly, needing only one day of training (Lee, 2009). Transcribers could also contribute to the 'ozbrl' email list (Round Table on Information Access for people with print disabilities, 2010c). Transition to UEB production has gone well, due to good support/training and developments in translation software (Duxbury Braille Translator) (Howse et al, 2010). Consultation From Jolley (2009a) Australian braille users were introduced to UEB early in its development through workshops run as early as 1995. This meant users were well informed and had opportunity to input in the development process Overall, the views of different groups varied, with educators strongly in favour of UEB, transcribers generally supportive, and users somewhat supportive, although with some concerns. Whilst users has opportunity to comment on UEB, ultimately it was member organisations of the ABA who voted on implementation. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 27 © RNIB 2011 Outcomes Ability to share materials with New Zealand which wasn't previously possible (Jolley, 2009a) Worked with Braille Authority of New Zealand Aotearoa Trust (BANZAT) to produce Trans-Tasman proficiency certificate in UEB (Jolley, 2009a; 2009b) Ability to share resources and offer more co-ordinated support to the Pacific Disability Forum (Jolley, 2009b) Increased awareness of braille and it's importance (Howse et al, 2010) Anecdotally, increase in braille users, among children in particular (Reported at ICEB Executive meeting, 15-17 July 2010). 2. Canada Key organisations Canadian Braille Authority (CBA): Organisation promoting braille throughout Canada Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB): Non-profit organisation providing services to blind and partially sighted Canadians Braille Authority of North America (BANA): Standards body for braille and tactile graphics across North America. Braille usage Not known. Timeline (From D. Bogart Personal Communication, April 2011) 2004: Canadian Braille Authority indicates its intention to move towards UEB 2005: CBA fund research into teacher and student impressions of UEB and the views of technical braille users. CNIB begins to produce titles in UEB for circulation to library readers, requesting feedback 2006: CNIB begins to produce one article in its monthly magazine in UEB, then entire issues of the magazine in UEB 2008: CNIB braille transcriber instructors update to UEB, all internal braille produced by CNIB is in UEB 2009: CBA fund some titles in UEB for users to borrow from the CNIB library, and provide materials for teachers to introduce to CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 28 © RNIB 2011 braille students (Nobel, 2010). CNIB begins to produce texts in UEB for Nigeria. 2010: In April, CBA adopt UEB as the 'preferred code to be implemented in Canada'. Pilots for updates for rehabilitation teachers and braille transcribers are initiated with the intent to put them on the website. Revision of the instruction manual is underway. 2011: CNIB developing UEB implementation plan. Implementation process From Canadian Braille Authority (not dated) Note: Whilst Canada have adopted UEB as a preferred code it has not yet been implemented. Organisation: An implementation committee was established with representatives of readers, educators, adult educators, and braille producers Users/braille teachers/transcribers: Encouraged to have a go learning UEB using the Australian UEB primer. CBA produced answers to the practice exercises to help people to check their work Information: CBA set up a blog giving information about UEB and interviews with people making the transition in Australia. Research: Focus groups were conducted asking teachers/students how they felt about UEB and any concerns they had. Consultation Not known. Outcomes UEB has not yet been implemented in Canada. 3. New Zealand Key organisations Braille Authority of New Zealand Aotearoa Trust (BANZAT) (Note: From August 2010. Formerly Braille Authority of New Zealand/Braille Literacy Panel) National body for standards setting and promotion of Braille, accrediting body of braille proficiency certificate Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind (RNZFB): non-profit organisation, the main provider of vision-related services to CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 29 © RNIB 2011 blind and partially sighted people in New Zealand, New Zealand's biggest braille producer Blind and Low Vision Education Network New Zealand (BLENNZ): network of educational services for blind and low vision children, involved in implementation of UEB in schools. Braille usage (Reported at ICEB Executive meeting, 15-17 July 2010) Around 300 braille users Since implementing UEB in 2008 there has been a resurgence in braille usage. Timeline Mid 1960s: New Zealand takes on English Braille American Edition 1997: Braille Authority of New Zealand oversee UEB workshops which gave New Zealand readers and transcribers of braille an early introduction to UEB 1998: New Zealand participate in the ICEB evaluation of UEB 2005: Further UEB workshops run. In November, New Zealand adopt UEB (Nobel and MacCuspie, 2009). Suggest implementation may take 'up to five years'. (Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 2006) January 2008: Young children start using UEB in education (Nobel and MacCuspie, 2009) July 2008: UEB Manual New Zealand Edition published (based on American training approach). (Braille Authority of New Zealand, 2010). Implementation process BANZ set up a subcommittee in 2006 to develop a UEB implementation plan. This focussed on four areas: curriculum support, teaching of adults, production and library services. The subcommittee involved representatives from all key stakeholder groups (braille users, producers, educators, librarians etc) (Howse et al, 2010). Education: Primary students taught UEB, though secondary students continued to use alternative technical codes (Nobel and MacCuspie, 2009; Howse et al, 2010). As students made the transition between primary/secondary, decisions about transition to UEB technical codes were made on a case by case basis (Howse et al, 2010) CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 30 © RNIB 2011 Reading materials: Books produced in UEB contain a symbols list for reference (Nobel and MacCuspie, 2009). Existing collection of library materials (in old codes) are retained but new material is produced in UEB, and over time the old materials will be phased out (Howse et al, 2010) Training: braille producers were trained early to ensure they could produce materials. Resource Teachers Vision (RTVs) were trained during a national teachers conference and had access to ongoing professional development provided regionally (Howse et al, 2010). Consultation Extensive consultation took place with braille users, teachers, producers and parents during 2005 before votes to adopt UEB. (Howse et al, 2010). All visual resource centres (supporting education) were canvassed by email, with 100% supporting the move to UEB. Some concern was raised around technical codes but overall it was felt that the majority would benefit. (Braille Authority of New Zealand, 2005) Prior to the decision to implement UEB, four issues of RNZFB's quarterly magazine were circulated in UEB to give readers exposure to the code. (M. Schnackenberg, Personal communication, March 2011). Outcomes Transition to UEB has raised the profile of braille. Links have been strengthened between Australia and New Zealand, which has also benefitted other pacific island regions (Howse et al, 2010) Anecdotal report that introduction of UEB has increased braille usage (Reported at ICEB Executive meeting, 15-17 July 2010). 4. Nigeria Key organisations National Braille Council of Nigeria (NABRACON): braille authority for Nigeria. Braille Usage Not known. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 31 © RNIB 2011 Timeline From NABRACON (2005) February 2005: NABRACON hold a workshop on UEB to inform educators, transcribers, producers and braille users with UEB. The NABRACON AGM follows this workshop at which they vote to adopt UEB in Nigeria. Implementation process Workshop run to familiarise stakeholders with the UEB code Decision taken that UEB would not be taught in schools until teaching materials were finalised and readily available (NABRACON, 2005) Books produced in UEB with a summary of changes in the code (Reported at ICEB Executive meeting, 15-17 July 2010). Consultation From NABRACON (2005) Over 90 participants from around Nigeria attended the UEB workshop in February 2005, representing end users, teachers and transcribers. Outcomes Not known. 5. South Africa Key organisations Blind SA: a non-profit organisation empowering blind people in South Africa South Africa Department of Arts and Culture. Braille usage Approximately 6000 braille readers. This figure is based on readers registered with Braille Services of Blind SA and the South African Library for the Blind, as well as braille learners in schools for the blind. (C. de Klerk, Personal communication, March 2011). Timeline From Braille South Africa (2004) May 2004: Braille South Africa adopt UEB and set out to modify their existing codes 2005: Start printing monthly magazines in UEB CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 32 © RNIB 2011 Early 2007: start implementing UEB in school grade one 2009: implement UEB for all literary materials in schools, technical codes to be phased in. Implementation process From Blind SA braille committee (2010) UEB training sessions run on request at schools and blind societies Producing new materials in UEB Rewriting existing braille materials (tutorials/reference manuals/teaching schemes) in UEB (In English and Afrikaans) A UEB rule book for beginners is being written The Department for Arts and Culture is conducting research into braille production to find ways to rationalise braille production making it quicker and more affordable. Consultation Not known. Outcomes Not known. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 33 © RNIB 2011 Appendix 2 UEB resources that have been developed UEB reference materials The Rules of Unified English Braille. [Australia] UEB symbols list – a list of new symbols in UEB [Australia] UEB in a nutshell – a brief outline of the UEB code and the reasoning behind it [Australia] The Hitchhikers Guide to UEB – quick reference information and examples of changes, aimed at teachers [New Zealand] Guidelines for technical material – information and examples to allow transcribers to produce technical material in UEB [produced by the Maths Focus Group, a subgroup of the ICEB UEB Rules Committee]. UEB teaching materials UEB Primer – based on the British Braille primer [Australia] Answers to exercises from the UEB primer (Australian edition) [Canada] UEB manual New Zealand Edition (based on American training approach) [New Zealand] Primary and secondary mathematics UEB training documents [Australia] Simply Touch and Read (STAR): Adult braille teaching course in UEB [New Zealand]. UEB courses Trans-Tasman Braille Proficiency Examination: Unified English Braille (jointly developed by Australia and New Zealand). Other UEB resources UEB Duxbury instructions – practical advice on using Duxbury braille translation software to produce UEB [Australia]. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 34 © RNIB 2011 Appendix 3 UEB adoption statements 1. South Africa, May 2004 UEB in South Africa South Africa made the decision to adopt UEB in May 2004: "Braille South Africa adopted a unified code for Braille in South Africa based on the UEBC and their existing codes will be modified where necessary. They are identifying a process for implementation in consultation with consumers, relevant national and provincial organizations, standard setting institutions and related organizations." In March 2006, Braille South Africa's President Christo De Klerk reported: "We have adopted the UEBC as the standard for English braille in South Africa and as the basis for the codes of our other ten languages. For about the past year we have been printing two monthly English magazines in the UEBC, one has a circulation of about 1500 readers. We had to do some work on our other languages, especially as far as diacritics are concerned, in preparation for the implementation of unified codes for them and have completed the process. "As soon as funding can be obtained, we can start work on creating Duxbury translation tables for unified codes for our other ten languages. Our braille authority, Braille SA, has decided to implement the UEBC in grade one in schools as from the beginning of 2007. Towards the end of this year we are planning UEBC training sessions for braille teachers and producers. In the meantime, we will work on UEBC awareness." At its meeting in May 2008, Braille SA resolved: To implement UEB for all literary materials in schools in 2009, and to phase in the use for technical materials such as mathematics as the younger children move on to higher grades. 2. Nigeria February 2005 The National Braille Council of Nigeria votes to accept the Unified English Braille Code (UEB) for future implementation in Nigeria. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 35 © RNIB 2011 National Braille Council of Nigeria (NABRACON) At the AGM of the National Braille Council of Nigeria (NABRACON), held in February 2005, a motion was moved to formally accept the UEB code for implementation in Nigeria. An overwhelming majority of delegates voted to adopt the UEB in Nigeria: 49 voted in favour, 1 against and 2 abstained. The motion to adopt the UEB in Nigeria was therefore carried and the logistics for its implementation in the country will be worked out in due course. The AGM followed a workshop on the UEB which was held in February 2005. The workshop was to acquaint educators, transcribers, producers and end-users with the Unified English Braille (UEB) Code. Over 90 participants from all parts of Nigeria, representing endusers, teachers and producers, attended the workshop. Neighbouring countries were invited to send representatives in an effort to introduce them to UEB and to encourage them to establish braille authorities in their respective countries, in line with resolutions passed at the General Assembly of ICEB in Toronto, April 2004. Only one country, Ghana, responded positively to this invitation. Two staff of the Ghana Braille Printing Press participated in the workshop (one visually impaired and the other sighted) and both also observed the AGM on the following day. The Ghanians went back enthusiastic about the UEB code and keen to explore the establishment of a braille authority in Ghana. A communiqué was issued at the end of the workshop which included the following resolutions: Resolutions 1. 2. We acknowledge the efforts of the International Council on English Braille in the formulation of this new code. We expect that they expedite action on finalizing the code as this will make Braille textbooks cheaper, more readily available and reflect even technological advancement. Training Institutions, Braille Production Units or Centres and Individual Transcribers should meet periodically to further acquaint themselves with the new code. CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 36 © RNIB 2011 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. We advise that the Unified English Braille Code should not be taught in schools until the materials for introducing the code to users are finalized and readily available. We enjoin other English-speaking countries to form Braille Authorities so that there will be a formidable African presence on the International Council on English Braille (ICEB). NABRACON observed with dismay, the absence of some States, Institutions and Examination Bodies connected with Braille usage at a workshop of this nature. We advise such bodies to avail themselves of such opportunities in view of the immense benefit accruable. We have observed a few areas needing clarification in the UEB and therefore recommend them to ICEB for further observation and consideration. NABRACON re-iterates the need for greater emphasis on the teaching of Braille in all Tertiary level institutions of Special Education in Nigeria. We adopt the UEB code for future use. A schedule is to be drawn up for implementing the adoption of the code in Nigeria. 3. Australia May 2005 Resolution regarding Unified English Braille passed by the Australian Braille Authority May 2005 Confirming that Unified English Braille (UEB) was accredited as an international standard for Braille by the International Council on English Braille in April 2004; and Recognising that Unified English Braille has substantial advantages over currently used Braille codes; and Acknowledging that some elements of UEB are yet to be finalised, and that reference documentation and training materials for teachers and transcribers are not currently available, This general meeting of the Australian Braille Authority, held on 14 May 2005 in Sydney, resolves: (a) that Unified English Braille is hereby adopted as the national standard for Braille in Australia; and CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 37 © RNIB 2011 (b) that organisations responsible for the teaching, production or promotion of Braille are encouraged to implement Unified English Braille within 5 years: (i) when there are reference and training resources available to enable a smooth and efficient transition; and (ii) at a time when, and in a manner in which, the benefits of the change will be maximised for their Braille readers and any adverse effects will be minimised. 4. New Zealand November 2005 New Zealand resolution unanimously adopted on 29 November 2005 reads: That the Braille Authority of New Zealand adopts the Unified English Braille Code, with the intention that by the end of 2006 an implementation plan, including funding, transition, training and timetable for the production, teaching and learning of braille be developed with all stakeholders involved with braille. 5. Canada April 2010 Resolution of the Canadian Braille Authority Adopted 24 April 2010 Whereas UEB has been adopted as a code for international use by the International Council on English Braille, and Whereas UEB has been adopted and implemented in other English-speaking countries thereby increasing the braille materials available in the same English braille code to people who are blind in the developed and developing world, and Whereas UEB is one code for literary and technical material which encourages a seamless approach to the instruction of technical subjects, and Whereas training materials are available, Therefore be it resolved that the Canadian Braille Authority adopt UEB as the preferred code to be implemented in Canada. To this end, CBA will provide the necessary leadership to bring provincial ministries on side with implementation and will help develop strategies to achieve successful outcomes for all stakeholders. Note: These adoption statements are available online at http://www.e-bility.com/roundtable/aba/ueb.php CAI-RR14 [04-2011] 38