abstract in word format

advertisement

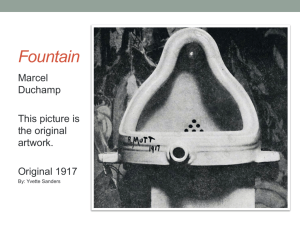

Gaffney 1 Peter Gaffney Dissertation Abstract Demiurgic Machines The Mechanics of the Dada Text In “Demiurgic Machines: The Mechanics of the Dada Text,” I explore the genealogy of modernity as a set of aesthetic and cultural practices heavily invested in the metaphorical system of the machine. Beginning with an overview of machine art during the early part of the 20th century, I proceed to analyze an intercontinental Dada movement that emerged in the period 1912–1922. Linking this movement to the writers and texts that inspired it (Raymond Roussel and Alfred Jarry, but also Max Stirner, Freud, and the Marquis de Sade), I consider how machines provide a working model for theories of production, suggesting a “demiurgic” reorganization of human thought and agency at the level of representation. What is unique about Dada is a strange amalgamation of word and image that suggests a radically new kind of representation: one that replaces the discourse of authenticity with a process of inscription that continuously reinvents the parameters for science, language and the work of art. The new subjectivity, I conclude, is characterized by hybridity, automatism, multiplicity and a troubling ambiguity between the self and its technological other. One example of this shift in artistic production can be found in the works of Raymond Roussel, a (reluctant) figure of the avant-garde and a key figure for New York Dada. In his poem Mon Ame, Roussel describes his soul as une étrange usine, identifying an inexhaustible potential for literary production in the alienated form of Man's technological other. Roussel's invention of le procédé anticipates Surrealist techniques of écriture automatique, as well as Freud's schematic for the ego as the enclosing 'surface' of an autonomous agency in the form of the unconscious. It is best known, however, as the primary inspiration behind Duchamp's machine art. It was through Roussel (and JeanPierre Brisset before him) that Duchamp arrived at his formula for the Large Glass (La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même), a production of images based entirely on a three-way correspondence between optics, kinetics, and the mechanics of language. By “reading” the Glass through Duchamp's notes (collected and published as La Boîte verte), we find a continuation of the artist's earlier experiments with movement on the pictorial surface, this time as a series of phantasmic events activated by the involuntary play of Gaffney 2 signifiers on the surface of language. Throughout Demiurgic Machines, I read the Dada text as an attempt to situate artistic production on this surface, outside the boundaries of human subjectivity, yet closely related to the interplay of words and images that constitutes the thinking subject. Other topics include: Brisset and les fous littéraires; Breton and automatism; intersubjective relations in Surrealism and de Sade; Dadaism and the technology of cinema; scientific discourse in Duchamp’s Boîte verte; Jarry’s cyborg, and other dreams of a mechanomorphic body; and Deleuze's conception of an impersonal and nonindividual transcendental field, exemplified by the “agency” of machines. Chapter 1: The Demiurge of New York Dada Here, I present the field of the dissertation: New York Dada, and other artists involved in this movement during the years 1912-1922 (principal years of Picabia’s and Duchamp’s machine art). I try to show how the sudden interest in machines and blueprints intersects with notions of the demiurge, mythological figure with the power to create—or destroy—the divine order of the universe. I also develop a criticism of Pierre Arnauld, who describes Picabia as an artist who has lost faith in the demiurgic powers of the artist (“comment ne pas voir que, dans le passage de l'âme orphique et de la subjectivité créatrice à l'âme-machine du monde moderne, une perte rédhibitoire s'est produite, que cette âme réifiée, sclérosée en mécanique répétitive, n'est plus que le fantôme de l'âme infiniment déliée de l'artiste démiurge...”)1. My argument involves a close reading of Benjamin’s essay on mechanical reproduction, analyzing the political implications of his expression “the decay of the aura.” Chapter 2: Blueprints For a Dada Machine In this chapter, I develop the argument that New York Dada’s machine art involved a production on the order of symbols and schemata, rather than an interest in the material conditions of real human (and machinic) productive forces. By looking at the transition in Duchamp and Picabia from their association with the Puteaux Cubists to their earliest experiments in machine art, I demonstate how these artists discovered the medium of the blueprint—a bridge between the world and its “mental and metaphysical expression,” to use Picabia’s expression. It is the blueprint, I argue, and not machines properly speaking, that inspired these artists, and gave them a key to understanding the demiurge, not as a craftsman of the physical universe, but as a figure of multilplicity at the center of scientific order. Chapter 3: Duchamp’s Mechanics of Surface In a close reading of Duchamp’s work during the period 1912-1923, together with related works and notes, I develop the argument that the Large Glass is itself a kind of blueprint. Yet it is one where the artist has found and inscribed certain mechanisms for a demiurge Gaffney 3 constantly in motion, constantly reinventing the order of the cosmos. After discussing Deleuze’s interpretation of Hume, I relate Duchamp’s notion of “a reality which would be possible” to other inventions of possible worlds, including Descartes’ treatise The World, and Jarryian Pataphysics (“the science of exceptions and imaginary solutions”). Chapter 4: How the Machine Speaks (!) In this chapter, I explore the mechanisms by which language produces—and reproduces— itself on un champ transcendantal impersonnel et pré-individuel (Deleuze), and the way Dada depicts these mechanisms through its literary and artistic creations. I also try to understand the precarious position in which the subject finds itself when faced with a production not of symbols, but of real material things: an idea of generation that links Lacan's analysis of Judge Schreber to Guattari's notion of an inconscient machinique, via Picabia's Fille née sans mère. In conclusion, I compare Villiers' automaton (L'Ève future)—particularly in its demonstration of an intersubjective mechanism for desire and language—to similar themes in Dada art. Chapter 5: Machinic Vision and the Cinematic Eye In the fifth and final chapter, I bring my findings to bear on the techniques of photography and cinema, with the questions: Is photography a way of seeing? Is the moving image a kind of consciousness? If Dada discovered an impersonal and non-individual transcendental field via the mechanics of surface, how did the pioneers of cinematography understand their production of images on the silver screen? Beginning with a discussion of a 'cinematic development' in the Large Glass, together with Benjamin's notion that Dada art was a precursor to cinema, I explore such early filmmakers as Germaine Dulac (La Roue, Disque 927, Thèmes et variations), René Clair (Entr'Acte), Buñuel (L'Âge d'Or, Chien andalou), and Duchamp himself (Anémic cinéma), as well as Paul Virilio's theories on cinema in relation to the technology of war (War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception). 1 Arnauld Pierre, Francis Picabia: La Peinture sans aura. Paris: Gallimard, 2002. p.126.