The United States and Europe: From Neutrality to War, 1921-1941

advertisement

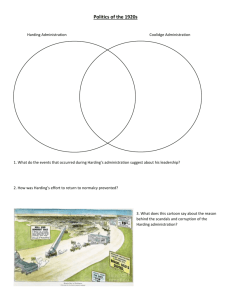

The United States and Europe: From Neutrality to War, 1921-1941 Lesson Plan #1: The Triumph of Pacifism I. Introduction Having experienced the horrors of modern war during one world war, Americans in the 1920s quickly concluded that there must not be another. A number of antiwar organizations had existed even before the war, but during the interwar period pacifism became the fastest-growing movement in America. The United States may have refused to join the League of Nations, but this did not prevent numerous American politicians, businessmen, journalists, and activists from making proposals for multilateral agreements on arms control and collective security. Through an examination of memoirs, photographs, and other primary source documents, this lesson will examine the rise of antiwar sentiment in the United States, as well as some of the concrete measures taken during the 1920s to prevent the outbreak of future wars. II. Guiding Question How was the rise of pacifism reflected in American diplomacy during the 1920s? III. Learning Objectives After completing this lesson, students should be able to: List the main reasons for the growth of antiwar sentiment after World War I Identify the U.S. foreign policy initiatives of the 1920s that aimed toward the prevention of war, and assess their strengths and weaknesses IV. Background Information for the Teacher It is arguable that at no time during the period of U.S. involvement in World War I (April 1917 – November 1918) was the war truly popular at home. In any case, it was not long after the war that Americans started wondering whether their country’s involvement had not been a serious mistake. To many liberals, the Treaty of Versailles, which the Allies forced Germany to sign in June 1919, made a mockery of President Wilson’s idealistic war aims. Instead of concluding a just settlement that would reform the international system and make future wars unlikely, the Allies, they concluded, had simply expanded their empires at the expense of their defeated foe. They began to question whether the loss of more than 120,000 dead, and nearly a quarter million wounded (not to mention the more than half a million Americans who died in 1918-1919 of Spanish Flu, which soldiers returning from Europe brought with them), was justified by this apparent return to “business as usual”? It was once common for historians to refer to the 1920s as a period of “isolationism,” thanks to the refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify the Versailles Treaty—and the subsequent failure of the United States to join the League of Nations. However, recent scholarship has focused on the ways in which, at both the public and private level, Americans remained committed to international efforts to prevent the outbreak of another war. U.S. bankers and businessmen, for example, with the active encouragement of the Harding and Coolidge administrations, concluded trade agreements with foreign firms, and extended loans on favorable terms to Germany in the belief that economic recovery was vital to the return of stability and the maintenance of peace. But while the efforts of American businessmen to promote economic stability in Europe were no doubt important, the activities of various antiwar organizations were far more visible. In the wake of the horror produced by World War I, pacifism was the country’s (indeed, the world’s) fastest-growing political movement. In the 1930s these groups would press for legislation that would keep the United States out of foreign wars; in the 1920s, however, the focus was still on international efforts to keep the peace—although without the sort of military commitments implied by the League of Nations. Because most pacifists believed that the sheer size of the armed forces in the years leading up to World War I had been an important cause of the war’s outbreak, one of the most consistent aims of the antiwar forces in the United States was the conclusion of arms control agreements. In this they were often able to make common cause with conservative Republicans who sought to decrease government spending of all types. It was this very alliance that resulted in the Washington Naval Conference of 1921-22, called to head off a naval arms race that seemed to be brewing among Great Britain, the United States, and Japan in the wake of World War I. In the resulting Five-Power Treaty the British, U.S., Japanese, French, and Italian delegations agreed to scrap—or at least to cancel construction of—significant numbers of capital ships (battleships, battlecruisers, and aircraft carriers), and to limit the overall tonnage of such ships in their navies to a ratio of 5:5:3:1.75:1.75. The U.S. Navy and its supporters were outraged, claiming that the country had lost its best opportunity to become the world’s preeminent naval power, but such views were given scant regard in the face of the overwhelming demand for peace and economy in government. Another important objective for the peace movement (both at home and abroad) in the 1920s was to have the waging of war declared a violation of international law. Few outside the community of antiwar organizations took this idea particularly seriously until 1927, when the French foreign minister, Aristide Briand, proposed a bilateral agreement with the United States in which both sides agreed never to go to war with one another. Frank B. Kellogg, the U.S. Secretary of State, suspected—rightly, it turned out—that this was a French attempt to lure the United States into an alliance, but he feared the political consequences of turning down such a seemingly innocuous proposal. He therefore offered to do Briand one better; why not, he suggested, make this a multilateral agreement in which all the world’s countries would be invited to renounce war “as an instrument of national policy”? Thus the Kellogg-Briand Pact was born. Pacifists embraced Kellogg-Briand as enthusiastically as they had welcomed the FivePower Pact, but there was widespread support for the agreement even outside the peace movement. There were some dissenters, however. Some objected that, lacking any means of enforcement, the treaty was useless; others claimed that, because the treaty included exceptions for wars of self-defense, the signatories would simply attempt to argue that any war they decided to wage was being fought in the name of national selfpreservation. In any case, such criticisms were quickly brushed aside, and the Senate ratified the Kellogg-Briand Pact by a vote of 85 to 1. It is difficult to assess the long-term importance of either the Five-Power Treaty or the Kellogg-Briand Pact in contributing to international peace. However, it is clear that certain of the signatories felt free to ignore or even repudiate the agreements whenever they became inconvenient. Japan announced in 1934 that it would no longer abide by the naval disarmament clauses of the Five-Power Treaty. As for Kellogg-Briand, the promise to renounce war did not prevent Japan from invading Manchuria in 1931; nor did it stand in the way of repeated acts of aggression by Japan, Italy, and Germany later in the decade. What is clear is that the agreements demonstrated the enthusiasm of Americans for any measure that promised the prevention of war. Once the agreements fell apart in the 1930s, however, antiwar activists turned their attention away from international cooperation to preserve peace, and toward legislation that would keep the United States out of wars that might break out anywhere else in the world. V. Preparing to Teach this Lesson Review the lesson plan. Locate and bookmark suggested materials and links from EDSITEment-reviewed websites used in this lesson. Download and print out selected documents and duplicate copies as necessary for student viewing. Download the Text Document for this lesson, available here as a PDF file. This file contains excerpted versions of the documents used in the various activities, as well as questions for students to answer. Print out and make an appropriate number of copies of the handouts you plan to use in class. Analyzing primary sources: If your students lack experience in dealing with primary sources, you might use one or more preliminary exercises to help them develop these skills. The Learning Page at the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress (http://memory.loc.gov/learn/start/prim_sources.html#) includes a set of such activities. Another useful resource is the Digital Classroom of the National Archives, which features a set of Document Analysis Worksheets (http://www.archives.gov/digital_classroom/lessons/analysis_worksheets/worksheets.htm l). Finally, History Matters offers helpful pages on “Making Sense of Documentary Photography” (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/Photos/) and “Making Sense of Maps” (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/maps/) which give helpful advice to teachers in getting their students to use such sources effectively. VI. Suggested Activities Activity #1: Why Pacifism? In the first activity students will learn about the pacifist sentiment which prevailed in discussions of foreign affairs during the 1920s. Begin by introducing students to the concept of pacifism, defined as “the belief that disputes between nations can and should be settled peacefully.” Lead a preliminary conversation with the class in which you ask the students whether, according to that definition, they believe themselves to be pacifists. Ask them under what circumstances they believe it is acceptable for the country to go to war. Next hand out Harry Elmer Barnes essay, “Balance Sheet of the First World War” http://www.greatwar.nl/frames/default-barnes.html, which is available at the site “The Heritage of the Great War, 1914-1918” (http://www.greatwar.nl/, linked from the EDSITEment-reviewed resource The World War I Document Archive [http://www.gwpda.org/] and reproduced on pages 1-2 of the Text Document. Ask the students to read Barnes’s essay as homework. Alternatively, if you have a lower achieving class, you may wish to read it aloud. After students have read the document, ask them what it tells them about how Americans felt about their country’s involvement in World War I. With their input, create a list on the board of the reasons why Barnes thought this involvement had been bad for the United States. Next, direct students to the following documents. All of these are available via the EDSITEment-reviewed resource World War I Document Archive [http://www.gwpda.org/]), but excerpts may be found on pages 3-5 of the Text Document. o Americans burying their dead, Bois de Consenvoye, France, 8 Nov 1918: http://www.gwpda.org/photos/bin08/imag0754.jpg o Dead French soldiers in the Argonne: http://www.gwpda.org/photos/bin03/imag0267.jpg o Ruined Church of Ablaire St-Nazaire in Artois: http://www.gwpda.org/photos/bin14/imag1335.jpg o Donald Hankey, A Student in Arms: http://www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/memoir/Student/Hankey4.html o The World War I diary of A.W. Miller: http://udel.edu/~mm/wwi/ o A Few of my Experiences whilst "On Active Service", by Charles Rooke: http://www.duffin.demon.co.uk/family/rooke.htm Ask students to imagine that they are members of the National Council for the Prevention of War, one of the country’s leading pacifist organizations during the 1920s. Students are to use the document excerpts above to create a political cartoon, either as homework or during class time, that will encourage people to embrace pacifism. If students need assistance on understanding political cartoons, direct them to the site “Analyzing a Thomas Nast Cartoon” (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/sia/cartoon.htm), part of the EDSITEment-reviewed resource History Matters (www.historymatters.gmu.edu). Activity #2: Arms Control and the Outlawry of War A determination to prevent the outbreak of future wars led pacifists to embrace international treaties for the limitation of armaments and for the outlawry of war. In this activity students will consider the Five-Power Treaty of 1922 and the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, both of which were applauded by pacifist organizations. Break the students into two groups. Assign the first half of the class the following set of documents relating to the Five-Power Treaty signed at the Washington Naval Conference. The first is available in its entirety at WWII Resources (http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/index.html, linked via the EDSITEment-reviewed resource Digital History [http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/]), while the other two may be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed resource Teaching American History (http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org). Excerpts are available on pages 6-9 of the Text Document. o Conference on the Limitation of Armament, 1922: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/pre-war/1922/nav_lim.html o William E. Borah, “Disarmament,” September 1922: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1496 o A Naval View of the Washington Treaties, April 1922, William Howard Gardiner: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1498 Assign the other half of the class the following set of documents concerning the KelloggBriand Pact, available in their entirety at the EDSITEment-reviewed resources The Avalon Project (http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon) and Teaching American History (http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org). Excerpts may be found on pages 11-15 of the text document. o Robert Lansing, “The Fallacy of ‘Outlaw War’,” August 16, 1924: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1499 o William E. Borah, “Public Opinion Outlaws War,” September 13, 1924: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1500 o Kellogg-Briand Pact, 1928: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/imt/kbpact.htm o Address by Edwin Borchard, “Renunciation of War,” August 22, 1928: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/kbpact/kbbor.htm Students are to pretend that they are presidential advisors who have been selected to review one these treaties to determine its effectiveness. Students are to individually read their documents, for homework or during class if time is available, and write a briefing to the president detailing their findings. A form has been provided for this briefing, on pages 10 and 16 of the Text Document. Once students have completed their briefing papers, which might be used as a graded assignment, reassemble students into their groups to discuss their conclusions. Students should come up with a list of positive and negatives from their documents. To conclude, have a class discussion in which a master list of these positives and negatives is created. How effective do students think these measures would be in preventing the outbreak of future wars? VII. Assessment Teachers might wish to grade students on the political cartoons that they created for the first activity, and/or the briefing paper they completed for the second. Alternatively, students might be asked to write a 5-7 paragraph essay that directly addresses the lesson’s guiding question: “How was the rise of pacifism reflected in American diplomacy during the 1920s?” Finally, students might be asked to identify and explain the significance of the following: Pacifism William E. Borah Five-Power Treaty Kellogg-Briand Pact VIII. Extending the Lesson The EDSITEment-reviewed site History Matters has a set of synopses of antiwar plays written during the 1930s (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5164). Teachers may wish to have groups of students write dialogue for some of these plays, and perform them in front of the class. The EDSITEment lesson plan “Poetry of The Great War: 'From Darkness to Light'?” (http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=602) invites students to consider how the war was remembered through poetry. In particular, teachers might wish to have students read Wilfred Owen’s powerful poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” (http://www.hcu.ox.ac.uk/jtap/warpoems.htm#12) and discuss what impact it might have had on the interwar peace movement. IX. EDSITEment-reviewed Web Resources Used in this Lesson The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/avalon.htm Kellogg-Briand Pact, 1928: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/kbpact/kbpact.htm Edwin Borchard, “Renunciation of War,” August 22, 1928: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/kbpact/kbbor.htm Digital History: http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/ WWII Resources: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/index.html Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington, November 12, 1921 – February 6, 1922: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/prewar/1922/nav_lim.html History Matters: http://historymatters.gmu.edu Analyzing a Thomas Nast Cartoon: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/sia/cartoon.htm Didactic Dramas: Antiwar Plays of the 1930s: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5164 Teaching American History: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org William E. Borah, “Disarmament,” September 1922: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=149 6 William Howard Gardiner, “A Naval View of the Conference,” April 1922: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=149 8 Robert Lansing, “The Fallacy of ‘Outlaw War’,” August 16, 1924: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=149 9 William E. Borah, “Public Opinion Outlaws War,” September 13, 1924: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=150 0 The World War I Document Archive: http://www.lib.byu.edu/%7Erdh/wwi/ World War One Image Archive: http://www.gwpda.org/imagarch.html Americans burying their dead, Bois de Consenvoye, France, 8 Nov 1918: http://www.gwpda.org/photos/bin08/imag0754.jpg Dead French soldiers in the Argonne: http://www.gwpda.org/photos/bin03/imag0267.jpg Ruined Church of Ablaire St-Nazaire in Artois: http://www.gwpda.org/photos/bin14/imag1335.jpg World War I, Memoirs, Memorials, Reminiscences: http://www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/memoir.html Donald Hankey, A Student in Arms: http://www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/memoir/Student/Hankey4.html The World War I diary of A.W. Miller: http://udel.edu/~mm/wwi/ A Few of my Experiences whilst "On Active Service", by Charles Rooke: http://www.duffin.demon.co.uk/family/rooke.htm The Heritage of the Great War, 1914-1918: http://www.greatwar.nl/ Harry Elmer Barnes, “The Disaster of America’s Entry in the Great War”: http://www.greatwar.nl/frames/default-barnes.html X. Additional Information Grade levels: 10-12 Subject Areas: U.S. History Time Required: 2-3 class periods Skills: o Analyzing and comparing first hand accounts o Debating key issues and topics o Interpreting written information o Information gathering o Making inferences and drawing conclusions o Observing and describing o Representing ideas and information orally, graphically and in writing. o Utilizing the writing process o Utilizing technology for research and study of primary source documents o Vocabulary development o Working collaboratively Standards Alignment: www.ncss.org/standards/strands/ o NCSS-2—Time, Continuity, and Change: The study of the ways human beings view themselves in and over time. o NCSS-3—People, Places and Environment: The study of people, places, and environments o NCSS-5—Individuals, Groups, and Institutions: The study of interactions among individuals, groups, and institutions. o NCSS-6—Power, Authority, and Governance: How people create and change structures of power, authority, and governance. Lesson Writers: o John Moser, Ashland University, Ashland, OH o Lori Hahn, West Branch High School, Morrisdale, PA Teacher/Student Resources: o Text Document Related EDSITEment Lesson Plans: o The Debate in the United States over the League of Nations o Poetry of the Great War: “From Darkness to Light”? o The Great War, Evaluating the Treaty of Versailles