Report of the Conference

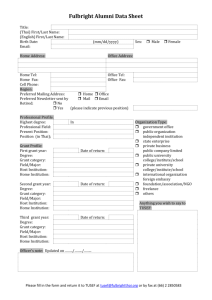

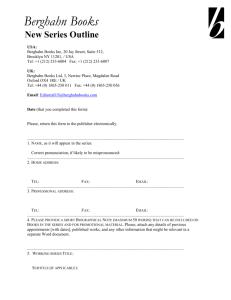

advertisement