Zero Hours Contracts Zero hours worker contracts have been the

advertisement

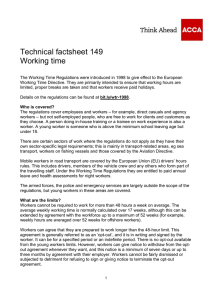

Zero Hours Contracts Zero hours worker contracts have been the subject of a huge amount of media and political comment over the course of the last six months or so. As you might expect, the trade unions have made their views clear with the General Secretary of Unison commenting that "the vast majority of workers are only on these contracts because they have no choice. They may give flexibility to a few, but the balance of power favours the employers and makes it hard for workers to complain". In response, Vince Cable, the Business Secretary, has said that "I think that at one end of the market there is exploitation taking place" and in December 2013 the Government launched a consultation to look into their use. A number of sports governing bodies and sports clubs legitimately use zero hours contracts, whether it is to staff specific events, to cover absences or to cover busy periods. In light of this, I have sought to highlight in this article some of the common issues concerning the use of zero hours contracts and have also provided a view on what the outcome of the Government's consultation might be. Common Issues There is no statutory definition of a zero hours contract. However, the term is generally used for contracts under which the relevant "employer" is not obliged to offer a minimum number of hours of work and the relevant worker is not obliged to accept any hours that are offered to them. Instead, the "employer", usually on a weekly or monthly basis, will indicate to the worker what hours are available and the worker then confirms which of those hours they can work, with the contract then setting out the terms that will apply where hours have been offered, accepted and are then worked. Zero hours contracts provide far greater flexibility (albeit also far less certainty) than a standard employment contract containing fixed hours and allow "employers" to increase their staffing arrangements during busy periods without having to make any commitments in relation to quieter periods. They are, however, also popular with "employers" as zero hours workers will not usually acquire the same employment rights as permanent (or even longerterm fixed-term) employees. This is because there will generally be no "mutuality of obligation" between the parties between assignments (i.e. during periods of no work, the "employer" is not obliged to offer work and the worker is not obliged to work). Mutuality of obligation is a fundamental requirement of any employment relationship and, as a result, if there is no mutuality of obligation during periods of no work, the worker will not be able to claim that their employment continued during the breaks between assignments. This, in turn, means they will not be able to amass sufficient continuous employment to benefit from the more important employee rights (for example, employees need two years' service to be entitled to a statutory redundancy payment if made redundant and new employees now need two years' service before they assume unfair dismissal rights). Despite the above, there are some cases where workers have been able to claim continuity of employment between assignments, for example, by claiming that a well-founded expectation of continuing work had refined itself into an enforceable "umbrella contract" spanning periods of work and periods of no work or that a break between assignments was a "temporary cessation in work" (a statutory term which again does not break continuity of employment). However, if the zero hours contract is well drafted, if offers of work have not become automatic and if the breaks between work are generally greater than the periods worked, it is likely to be very difficult for workers to claim continuity across assignments. Whilst, as set out, zero hours workers are likely to struggle to claim continuity of employment and therefore, for example, unfair dismissal rights, it is important to remember that they will, even if they only have "worker" status, be entitled to paid holiday and, if the relevant earnings thresholds are met, to be automatically enrolled in a qualifying pension scheme. In relation to holiday, it is generally accepted that zero hours workers will accrue hours of leave at a rate of 12.07% of the hours actually worked and any holiday pay should be based on their average pay (including overtime and any relevant bonuses) in the twelve working weeks prior to their period of leave. What next? The political and media controversy partly links to the fact that zero hours contracts can result in workers not attaining employee rights. In addition, there have been examples of "employers" not, for example, paying workers their holiday pay entitlement (indeed, it has been alleged in the press that Sports Direct, which is said to have around 20,000 zero hours workers, is currently facing claims from a number of workers for unpaid holiday pay). However, there is also controversy in a number of other more specific areas: (i) in some sectors (albeit, not as far as I am aware, amongst governing bodies or sports clubs) contracts have included exclusivity clauses preventing the worker from working for third parties, even though they have no guarantee of hours under that contract; (ii) some contracts used have lacked transparency and do not make it clear in plain English that no minimum hours are guaranteed; (iii) the use of the contracts are said to have pushed the balance of power even further towards the "employer" as workers will be reluctant to complain if they think it will result in their hours being cut or in no hours being offered at all; and (iv) by definition, the contracts provide workers with uncertain levels of earnings. The Government consultation is seeking views in all of these areas and closes on 13 March 2014. In terms of next steps, I cannot see any prospect of the contracts being banned (which is what some of the unions have been pushing for) given they fulfil a legitimate need and given, in many cases, the worker will also benefit from the flexibility they provide. Any changes that do result from the consultation are therefore likely to be around the fringes. For example, I can see that exclusivity clauses might be banned, save in exceptional cases, where the worker will have access to confidential information, and I can also see greater emphasis being placed on the need for clear wording in the contract explaining that no minimum level of hours are guaranteed. However, I would be very surprised if many more legislative changes were made. In summary, zero hours contracts, when used correctly, do serve a valuable purpose and certainly sports governing bodies and clubs (as opposed to other sectors, such as the retail sector) are not the focus of the current review. Given that the CIPD estimates that only 4% of the workforce are on zero hours contracts, the recent media and political comment on their use is also likely to prove to be something of a storm in the teacup. David Hunt Farrer & Co david.hunt@farrer.co.uk