Targeting the Achilles Heel of Podiatric Medical NegligenceBY

advertisement

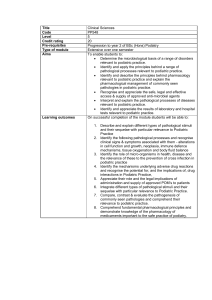

Targeting the Achilles Heel of Podiatric Medical NegligenceBY: Charles F. Fenton III, DPM, JD Foot Law memberTRIAL magazine, June 1996, page 40:Reprinted with permission of TRIAL (June 1996) Copyright the Association of Trial lawyers of America. Podiatrists are a small group--there are only about 14,000 in the United States (1). And while most people have, some inkling of what podiatrists do, their contributions to the medical profession are often misinterpreted or misunderstood. The confusion surrounding podiatric medicine exists partly because podiatrists are held to different standards than medical doctors. For example, there is no consistent board certification or state law to regulate the scope of podiatric practice.Small wonder, then, that podiatric negligence insurance companies often use and reuse the same law firms to defend their clients. These firms rely on acoterie of podiatric expert witnesses, who are able to fine-tune their testimony in each subsequent case. Plaintiffs' lawyers handling these cases for the first time must understand that they will be at a distinct tactical disadvantage--even if they are experienced in medical negligence cases.This article addresses the inconsistencies and vagaries of podiatric practice that may not be apparent to lawyers who are newcomers to this area. It will also show how plaintiffs' attorneys can use these inconsistencies effectively against the defense team at trial.To understand podiatric medicine, attorneys must first understand what it treats: the foot. And in some states, the ankle and leg as well. Within the foot are many structures, including nerves, arteries, bones, joints, ligaments, tendons, muscles, and skin. Many systemic diseases, including diabetes, gout, arthritis, and nerve and circulatory conditions, can affect the foot.The practice of podiatry, then, overlaps with other specialty fields of medicine. In fact, podiatrists provide only about 39 percent of the foot care tendered in the United States. Orthopedic surgeons provide about 13 percent, other physicians provide about 37 percent, and physical therapists and others provide about 11 percent (2).Many podiatrists practice general podiatry. They treat a wide range of conditions, from nail fungus to structural deformities. They also perform advanced surgery using techniques involving lasers and endoscopes--instruments used to examine the interiors of organs and vessels. As general practitioners, many podiatrists lack adequate training in specialized techniques. TRAINING Podiatrists must graduate from one of seven accredited schools of podiatric medicine in the United States (3). These schools offer four-year programs similar to those of medical schools. Unlike medical doctors, however, podiatrists in many states are not required to serve an internship or residency once they graduate from podiatry school. Some podiatrists, however, do serve in these programs (4).An obvious concern, then, is how podiatrists who have not served a surgical residency learn to perform surgery. As medieval as it seems, many simply practice on their own patients and learn from their own mistakes. Some also complete what is called a preceptorship.A preceptorship is much like an unofficial apprenticeship, allowing a new graduate to work side by side with an experienced podiatric surgeon. Serving a preceptorship after completing an accredited residency program is a bona fide way for new practitioners to hone their skills and to acquire clinical knowledge, but by itself, it is no way to learn surgery. The problem of inconsistent training is not limited to older practitioners. New graduates are also inconsistently trained. Ironically, the Council on Podiatric Medical Education (CPME) has identified a 200-position shortage in residency positions for 1996 (5). CPME is part of the American Podiatric Medical Association! which accredits the schools of podiatry, as well as the residency and continuing education programs. CPME also oversees the certification boards approved by the association. Even the training of podiatrists who complete a residency is inconsistent. Some residency programs focus on medical concerns, such as the RPR program, a 12-month Rotating Podiatric Residency program. Others focus on nonsurgical orthopedic concerns, such as the FOR program, a 12-month Podiatric Orthopedic Residency program. Still others focus on surgery. Time spent in residency also varies. Some podiatrists serve only a years others, up to three. Only about 32 percent of the approved podiatric residency programs are two-year programs. Residency programs lasting longer than two years are uncommon (6). Even though training is inconsistent, most podiatrists consider themselves surgeons, and most perform foot and ankle surgery.A main goal of discovery in a podiatric medical negligence case is determining the extent of the training and experience of both the defendant podiatrist and the defense podiatric expert witness. It is vital to establish whether they served a residency, the type of residency, its length, and the type of surgical cases they were exposed to during the residency. It is also wise to request a copy of the podiatrist's resident surgical log as well as his or her surgical log for the past two years.Podiatrists who serve on hospital staffs often have procedural restrictions placed on them based on their training and experience. For example, a podiatrist may have hospital surgical privileges limited to performing surgery only on the forefoot or to only performing soft tissue procedures. Additionally, a podiatrist's privileges may be limited to exclude advanced procedures such as the use of a laser, an arthroscope, or an endoscope. However, podiatrists in private practice who perform surgery in their offices are not under any such restrictions. Attorneys should get a copy of the defendant podiatrist's delineation of privileges at all hospitals where he or she is on staff. Thes@ records may prove useful in determining whether a podiatrist has exceeded his or her privileges (7). STATE LAWS The scope of podiatry practice varies widely in all 50 states. While a medical doctor is licensed in most states to perform "diagnosis or treatment . . . of human beings," (8) a podiatrist is considered a limited-license practitioner whose scope of practice is regulated by state laws. Some states, like Georgia, allow podiatrists to practice medicine and perform surgery on the foot and leg (9). Florida limits podiatry to the foot and leg, below the tibial tubercle (10). Other states--including Alabama, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, and Texas--restrict podiatric practice to the feet (11).It becomes problematic, then, when podiatrists receive post-graduate training in a state with restrictive laws and then move to a state with liberal laws. These podiatrists are inadequately trained to practice within the full scope of their licenses. Nonetheless, they often practice up to the limit that a state law allows.Attorneys should research the limits of the podiatry act in the defendant's home state and compare it to the act in the state where the podiatrist was trained. This investigation may reveal the podiatrist was inadequately trained to perform the procedure in question. It is also important to research any recent changes to the act in the home state.For example, in Georgia, the General Assembly recently expanded its podiatry act to allow podiatrists to perform certain amputations (12). Now many established practitioners who lack the necessary training and experience are licensed to perform this procedure. Also, even if an established practitioner was schooled in amputations as a podiatric resident, it is likely that the training occurred many years ago and may be outdated. CERTIFYING BOARDS The American Podiatric Medical Association (APMA) allows several boards to certify podiatrists (13). However, APMA recognizes only one board--the American Board of Podiatric Surgery (ABPS)--for certifying competency in performing ankle and foot surgery. This certification is not all that common. Only about 3,700 podiatrists are certified by this board, and only about 2,500 of those are certified in both ankle and foot surgery (14).Unrecognized boards have been established by podiatrists who are dissatisfied with the ABPS certifying procedures. Some podiatrists refer to ABPS boardcertified status as elitist. In reality, the ABPS exam is tough but fair. It is inconsistent training and inconsistent state laws that make it difficult for many podiatrists to qualify for and pass the exam, and this frustrates them. During discovery, it is important to uncover whether the podiatrist is board-certified. An attorney can use this information by discovering which board has certified the podiatrist in surgery. If the podiatrist is not certified by ABPS, the attorney should ascertain whether the podiatrist has failed the ABPS certification exam or whether the podiatrist does not meet the criteria for certification by ABPS. If the podiatrist is certified by another board and if the attorney can demonstrate that that board is not approved by APMA, the attorney may be able to discredit the podiatrist's board-certified status. This is especially true if the attorney can show that the defendant is not qualified to take the exam offered by the APMArecognized board.It is also important to find out whether the podiatrist is board-certified in surgery or in primary podiatric medicine. If the podiatrist is board-certified in primary podiatric medicine and the claim involves a nonsurgical office procedure, the podiatrist may be adequately board-certified. However, if the podiatrist is board-certified in primary podiatric medicine and not in surgery and the claim involves bone surgery of the foot, the podiatrist would not be adequately board-certified.Was the podiatrist certified by examination or by grandfathering? Was the podiatrist board-certified in foot and ankle surgery or only in forefoot surgery? If the podiatrist is board-certified only in forefoot surgery, was the surgery at issue rear-foot surgery? OFFICE SURGERY Podiatry offices are not hospitals, and most are not certified ambulatory care centers. Nonetheless, many podiatrists perform bone surgeries in their offices, often in an examining room, where there is an increased risk of infection and a risk of delayed definitive treatment if a medical emergency occurs.For example, most podiatry offices are not equipped with defibrillatory. If a patient developed a heart attack during office surgery, then initial first aid and CPR would be the only treatment rendered until the patient was transported to a hospital. However, if such an emergency occurred in a hospital operating room, treatment and defibrillation would occur in seconds.Many offices do not implement adequate policies and procedures to properly perform in-office bone surgery. These guidelines are important to prevent complications, most notably, postoperative infections. Prevention of these infections includes proper cleaning of the office surgical site, proper air flow and filtration of particles, and proper construction of the surgical site to limit areas that could accumulate dust. If the client had bone surgery in an office, discovery should be used to determine whether the podiatrist followed adequate policies and procedures for surgery (15). The attorney should also determine whether proper preoperative blood tests were performed. What were the results? Was the patient's primary-care physician consulted before the surgery? Was the patient advised of the increased risks of performing surgery in an office, and is this consent documented?Proper preoperative preparation should also be established. For example, the sterilizer's maintenance records should be obtained. Was the sterilizer routinely tested by the spore method? Spore testing involves placing a packet of bacterial spores inside a surgical pack and then sterilizing it. After sterilization, the packet is removed and the spores are placed onto a culture medium that is placed in an incubator. If the spores germinate, the sterilizer is functioning improperly. Many podiatry offices are lax in this respect. The podiatrists either do not perform spore testing or do it inconsistently.In some cases, it may be appropriate to inspect and photograph the place where surgery was performed. This may reveal that the room was inadequate for bone surgery. For example, was the surgery performed in a treatment room obviously set up only to debride fungus from infected toenails? ORTHOPEDIC SURGEONS Some podiatrists fear that a patient with postoperative complication will seek treatment from an orthopedic surgeon--whose surgical training far exceeds their own. Many patients with complications give greater credence to the opinion of an orthopedic surgeonEven some defense attorneys fear orthopedic surgeons. They make the defense attorney's job more difficult. The practices of an orthopedic surgeon and a podiatrist overlap. Although the former's training far exceeds the latter's, a well-trained podiatrist may have a lot more experience in foot surgery than a generally trained orthopedic surgeon. When the orthopedic surgeon testifies, the defense attorney faces an uphill battle making this distinction.In some states--such as New York and Ohio--orthopedic surgeons can testify as expert witnesses against a podiatrist, (16) but in other states--such as Colorado and Utah--they are not qualified to do so (17). When an orthopedic surgeon may testify, often he performed. An infectious disease specialist should be consulted to manage the intravenous antibiotic therapy. Finally, it is important to ascertain whether the podiatrist ensured continued treatment once the patient left the hospital.Patients with diabetes or peripheral vascular disease are considered high-risk. They are often advised to seek periodic professional care for their feet because if they cut themselves during foot care! they are at an increased risk of infection. A professional, such as a podiatrist, is less likely to cut a patient during foot care, and if there is a cut, will likely know how to reduce the risk of infection. Podiatrists may be found liable if they cut a diabetic patient and fail to provide adequate medication or treatment (20).Because podiatrists often treat high-risk patients, it is important that the patient be properly evaluated before surgery. For example, if a diabetic's blood sugar is extremely elevated, this may slow healing, increasing the risk of postoperative infection.After a minor injury or surgery, some patients can develop what is called reflex sympathetic dystrophy. If this condition goes untreated--or if treatment is delayed==the results can be devastating. Limbs can become sore and shrivel from atrophy. In some cases, the pain is so debilitating that the patient elects amputation.A patient who does not respond to treatment after a minor injury or surgery and suffers a disproportionate amount of pain should be referred for definitive treatment. When the disease is treated early, complications can be significantly reduced. But since podiatrists of ten delay making a proper referral, complications are common.Pain caused by heel spurs is a condition podiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, and other physicians have treated for years with varying degrees of success. Recently, podiatrists have been using endoscopy to sever the ligament that attaches to the heel spur. The procedure is the endoscopic planter fasciotomy discussed above.Podiatrists have been debating the efficacy and overuse of this procedure, primarily because of significant postoperative complications. Some of these complications include continued heel pain, increased heel pain, painful nerve entrapment, and midtarsal syndrome. Midtarsal syndrome involves pain, often self-limiting, on the outside-middle part of the foot that can be as severe as the initial heel pain. The use of endoscopy is also debated because not all heel pain is the result of a tight planter fascia ligament. Excessive weight, nerve entrapment, gout, stress fractures, and various arthritic conditions may also cause heel pain. Endoscopy is inappropriate when heel pain results from these conditions. Additionally, there is debate that some podiatrists are overusing the procedure for financial gain. IMPROPER BILLING Although improper billing does not constitute negligence, attorneys should always check billing records. Some podiatrists bill improperly. Some will use improper coding or upcoding. Upcoding involves submitting an insurance claim that describes a service more involved than the service actually delivered. This results in a higher fee. Other podiatrists will fail to use proper modifiers, unbundle, overbill, or fail to abide by copayment provisions. These are discussed below.The standard for identifying services rendered is the Physicians' Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), published by the American Medical Association (21). The book delineates most procedures performed by physicians. Insurance companies and physicians use the book as a guide for billing and reimbursement. A number is assigned to each procedure.Podiatric surgery often encompasses multiple procedures performed at the same time, such as surgery on four toes. When this surgery is billed, all procedures after the primary procedure are assigned a suffix of -51 (22). This signifies that the procedure is a multiple procedure and billing is often at 50 percent of the primary procedure. A few practitioners omit the modifier and bill 100 percent of their fee for each procedure. They do not expect to receive full payment, but they figure the odds are good that the insurance company will pay more than if they had included the appropriate modifiers.Procedures described in the CPT involve separate tasks that must be completed in order to perform the procedure. Instead of billing for the procedure performed, some practitioners will unbundle the charges, or bill for each component separately. The practical effect of this is overcharging. When a component is considered an integral part of a total service, it should not be billed separately. When it is, the surgeon is essentially stating that he or she performed all the integral parts of the total service plus the separate component. In effect, the surgeon is billing twice for the same procedure. This is unethical in any profession.For example, podiatrists who perform a bunion repair with metatarsal osteotomy procedure are supposed to bill with the descriptive CPT code 28296. Unethical podiatrists, however, would bill with the OPT codes 28022 (arthrotomy of metatarsophalangeal joint); 28306 (first metatarsal osteotomy); 28288 (ostectomy, first metatarsal head); 28234 (tenotomy); and other codes they think will not raise questions (23). Most insurance companies require a patient to assume part of the financial liability for services. These requirements take the form of deductibles, co-payments, and co-insurances. The requirement ensures that the patient--having a financial stake in the treatment--will be a prudent buyer of medical services.Some physicians, including some podiatrists, waive these patient payments and accept whatever insurance pays as payment in full. When a physician waives patient payments, patients often feel they are being treated for free. Since the patients are no longer "prudent buyers," the physician often increases the fee and the number of services performed.Improper billing is unethical and sometimes constitutes insurance fraud. And it will always cast the defendant in a bad light in the jury's eyes. SWORD FOR THE ATTORNEY To win a podiatric negligence case, attorneys need to develop an understanding of both podiatric procedures and the underlyinginconsistencies of podiatry training. By understanding how the podiatry community works, plaintiffs' attorneys can turn that knowledge into a sword, striking a fatal blow to the defense's Achilles heel. Notes1. Judith A. Rubenstein, Push On! Better Times Up Ahead, PODIATRY TODAY, Jan. 1996, at 20. 2. AMERICAN PODIATRIC MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, AMERICAN PODIATRIC MED. ASS'N MAPS & GRAPHS: SUMMARY OF INFORMATION ON FOOT AND ANKLE PROBLEMS, FOOT CARE, AND PODIATRIC PHYSICIANS 1 (1995) [hereafter MAPS & GRAPHS]. 3. AMERICAN PODIATRY ASS'N, DESK REFERENCE 1995-96, at 16 (1995)[hereafter DESK REFERENCE]. 4. As of 1990, only 59 percent of practicing podiatrists had completed an approved entrylevel residency program. MAPS & GRAPHS, supra note 2, at 2. 5. Zach Taylor, Unplaced and Anxious: Students Endure Residency Shortfall, APMA NEWS, Mar. 1996, at 42. 6. MAPS & GRAPHS, supra note 2, at 45. As of 1991, only 63 percent of the available podiatric residency programs were considered surgical residencies. Id. at 47. 7. See, e.g., Songer v. Jervis, 763 S.W.2d 132 (Ky. Ct. App. 1988) (discussing whether a podiatrist exceeded his delineation of privileges). 8. GA. CODE ANN. § 43-34-20(3) (1994).9. Id. § 43-35-3(5)(A). 10. FLA. STAT. ANN. ~ 461.003(3) (West 1991). 11. Only 30 states include the ankle in the scope of practice of podiatrists. MAPS ~ GRAPHS, supra note 2, at 64. Seventeen states still allow a podiatrist who has not served ~ residency to receive a license. Id. at 63. ALA. CODE § 34-24-230(2) (1991) (defining the scope of podiatry practice to the foot); ILL. ANN. STAT. ch. 111 pare. 4906 (SmithHurd) (1993) (defining the scope of podiatry practice to the foot); KAN. STAT. ANN. § 65-2001(c) (1992) (defining the scope of podiatry practice to the foot); MASS. GEN. LAWS ANN. ah. 112, § 13 (West 1995) (defining the scope of podiatry practice to the foot) TEX. REV. CIV. STAT. ANN. HEALTH § 4567(a) (West Supp. 1996) (defining the scope of podiatry practice to the foot) 12. See GA. CODE ANN. § 43-35-3(5)(E)-(F)(1994). Compare OKLA. STAT. ANN. tit. 59 § 136(3) (West 1989) (limiting the practice of podiatry to the foot) with OKLA. STAT. ANN. tit. 59 § 142A (West Supp. 1996) (defining the scope of practice of podiatry to include the foot and ankle). 13. The American Podiatric Medical Association currently recognizes the American Board of Podiatric Orthopedics h Primary Podiatric Medicine, the American Board of Podiatric Public Health, and the American Board of Podiatric Surgery. DESK REFERENCE, supra note 3, at 16.14. Membership Statistics Before 1994 Examination, NEWSLETTER (American Board of Podiatric Surgery), July 1995, at 5. Sixty-four percent of active podiatrists are not certified by any recognized board. MAPS & GRAPHS, supra note 2, at 51. 15. See generally CHARLES F. FENTON III & PETER MARSHAL HARVEY, PODIATRY INSURANCE CO. OF AMERICA, OFFICE-BASED SURGERY: A RISK MANAGEMENT MANUAL FOR DOCTORS OF PODIATRIC MEDICINE (1992). 16. Anderson v. Stephen M. Donis, D.P.M.P.C., 541 N.Y.S.2d 25 (App. Div. 1989) (orthopedic surgeon who had performed foot tenotomies qualified to testify as an expert against a podiatrist), King v. LaKamp, 553 N.E.2d 701 (Ohio Ct. App. 1988) (orthopedic surgeon who testified as to the orthopedic standard of care was qualified as an expert against a podiatrist). 17. Melville v. Southward, 791 P.2d 383 (solo. 1990) (orthopedic surgeon unfamiliar with the standard of care in podiatry not qualified to testify as an expert against a podiatrist);