Running head: Probability Learning

advertisement

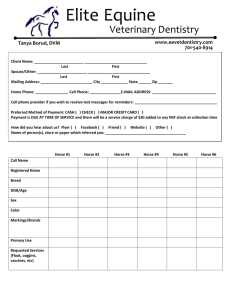

Effect of Instruction 11/13/01 Effects of Advice on Performance in a Browser-Based Probability Learning Task Michael H. Birnbaum and Sandra V. Wakcher1 California State University, Fullerton and Decision Research Center, Fullerton Mailing Address: Prof. Michael H. Birnbaum Department of Psychology California State University, Fullerton H-830M P.O. Box 6846 Fullerton, CA 92834-6846 Email address: mbirnbaum@fullerton.edu Phone: 714-278-7653 Acknowledgements: This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation to California State University, Fullerton, SBR-9410572 and SES 99-86436. 1 Effect of Instruction 2 Abstract The present study extended Birnbaum’s (in press) browser-based probability learning experiment in order to test the effects of advice on performance. Birnbaum reported that people in both Web and lab studies tend to match the probability of their predictions to the probability of each event, consistent with findings of previous studies. The optimal strategy is to consistently choose the more frequent event; probability matching produces sub-optimal performance. We investigated manipulations that we thought would improve performance. The present study compared Birnbaum’s abstract scenario against a horse race scenario in which participants predicted the winner in each of a series of races between two horses. Two groups of learners (one in each scenario) also received extra advice including explicit instructions to maximize probability correct, information concerning the more probable event, and the recommendation that the best strategy is to consistently choose the more probable event. Results showed minimal effects of horse versus abstract task; however, extra advice significantly improved both percent correct in the task and the number of learners who employed a nearly optimal strategy. Effect of Instruction 3 Birnbaum (in press) compared performance in the classical probability learning paradigm in the lab and on the Web. Consistent with other lab versus Web comparisons (Birnbaum, 1999; 2001; Krantz & Dalal, 2000), these two ways of conducting the research give quite similar results, once the demographics of the samples are taken into consideration. Birnbaum’s materials (HTML and JavaScript code) are contained in a single file, and are available from the following URL: http://psych.fullerton.edu/mbirnbaum/psych466/chap_18/ProbLearn.htm In the binary probability learning task, the learner’s task is to push one of two buttons in order to predict which of two events will occur on the next trial. After each prediction, the learner is given the correct event. If the sequence of events is truly random and if learners do not possess paranormal abilities, then the optimal strategy is to figure out which event is more likely, and to consistently predict that event on every trial. However, the typical finding in these studies is that people tend to match the proportions of their predictions of the events to the probabilities of the events (give a list here of about 8 refs of such studies). Such behavior is called “probability matching,” and it leads to sub-optimal performance in the task (Tversky & Edwards, 1966 and other refs here on probability matching as sub-optimal). Consistent with previous tests of probability learning Birnbaum (in press) also found evidence for probability matching. (in both laboratory and Web-based studies). In a browserbased study, learners predicted which of two abstract events (R1 or R2) would happen next by clicking buttons and were given feedback as to whether they were right or wrong on each trial. Birnbaum found that judges did not consistently choose the more likely event. Instead, they matched their probability of clicking R2 to the probability that the R2 event actually occurred. To see why probability matching is sub-optimal, consider predicting the color of the next marble drawn at random from an urn, with marbles replaced and re-mixed before each draw. If Effect of Instruction 4 there are 70% red marbles and 30% blue marbles, a person should always predict that the next marble is “red,” which will result in 70% correct. However, if a person matches probabilities, guessing “red” on 70% of trials and guessing “blue” 30% of the time, the person will end up with only 58% correct. This sum is the result of guessing “red” when red occurs (.7 X .7 = .49) plus guessing “blue” when blue occurs (.3 X .3 = .09); the probability of being correct is therefore only .58. In general, if p is the proportion of the more frequent outcome of a Bernoulli trial, the percentage correct for the optimal strategy (always guess the more frequent event) is p and the 2 2 probability correct for the probability matching strategy is only p (1 p) . In early research, probability matching was seen as the consequence of a probabilistic reinforcement model that described how people and other animals learned (Estes, 1950; 1994; Bowers, 1994). Probability matching, however, could also result from attempts to learn patterns or sequences that have been experienced by the learner (Gal & Baron, 1996; list other refs here on pattern or strategies). Perhaps if people understood that the events are truly random, rather than coming in some pattern, they would not try to use strategies that result in poorer performance. (references here to strategy and instruction studies). Nies (1962) manipulated instructions that presented to learners to determine if people could profit by instruction. Participants were divided into three groups and were instructed to predict whether a marble rolling out of a box would be red or blue with the goal of getting as many correct predictions as possible. Two of the three groups were given additional instructions: one group was told that there were 100 marbles in the box and that 70 were red and 30 were blue, and a second group was told that the marbles roll out in a pattern. The third group received no additional instructions. Nies found that the group that was told the proportion of red and blue marbles achieved a higher percentage correct than the other two groups. However, only 4% of Effect of Instruction 5 the learners used the optimal strategy of always predicting the more likely marble. (4% overall or in which group?) In this study, we attempted to construct a scenario and advice that we thought would produce more optimal behavior than the instructions used by Nies. First, we devised a horse race scenario, based on the notion that people might respond differently with a familiar mechanism underlying the random series. Horse racing, which is a popular gambling scenario, might help people understand as well the goal of maximizing the number of correct predictions, rather than trying to be correct with equal conditional probability on each event (cf. Herrnstein, 1990). Second, we created additional advice that were thought would improve performance. People were told to imagine winning $100 for each correct prediction and losing $100 for each incorrect prediction (cf. Bereby-Meyer and Erev and other refs). We thought that the use of money in the advice would make clearer the goal of maximizing percentage correct. Advice also included the explicit advice that the best strategy is to determine as quickly as possible the more frequent event and then to stick with it. Finally, the extra advice included honest information about the underlying probability of the event. Method Participants performed a probability learning task in which they made binary predictions. The scenario was either a horse race or an abstract event. Learners in the horse race condition were asked to predict the outcome of a series of horse races by clicking on buttons labeled Horse A or Horse B. In the abstract scenario, learners were asked to predict the occurrence of an event by clicking on buttons R1 or R2. Each learner completed one warm-up game and five experimental games of 100 races/trials each. After each game, judges were asked to judge their performance and the probabilities of events. Participants were assigned to one of two groups. Effect of Instruction 6 One group received advice that could improve performance, and the other group served as control. Instructions and Conditions Horse race scenario. Judges in this scenario were instructed to try to predict on each trial which of two horses will win the next race by clicking buttons labeled Horse A or Horse B. Information was varied between groups who either received advice or no advice. Advice consisted of strategy, money, and probability information. Strategy advice was to “find the more likely horse and stick with it.” Judges were also told to “imagine you win or lose $100 for each race you predict right or wrong.” In addition, information from an oddsmaker specified, for example, “Horse A should win 20% and B should win 80%.” Learners were also advised to pay close attention to the oddsmaker’s advice. The oddsmaker information accurately presented the true probabilities of horse A and B winning, which varied randomly from game to game and subject to subject, but was fixed within each game. Abstract scenario. Two conditions used abstract events instead of horses, as in Birnbaum (in press). Judges were instructed to try to predict whether “R1” or “R2” would occur. One of the groups received the corresponding additional advice as in the horse race condition, reworded for the abstract events, and the other group served as the control. Design The between-subjects variables were the Scenario (horse race scenario/abstract scenario) and Advice (advice/no advice) presented to judges. The between-subjects design was a 2 x 2, Scenario by Advice factorial design. Judges were assigned to one of the four conditions according to their birth months. Effect of Instruction 7 The within-subjects variables were probability of events and games. Each judge participated in five games of 100 trials each. For each game, the probability of an event was chosen randomly (and uniformly) from the set 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, or 0.9. Probabilities were independent from game to game and subject to subject. Because the events were randomly sampled, the realized proportions might differ slightly from the actual probabilities. Materials and Procedure To view complete materials, visit the following URL and click on different months to experience the different conditions: http://psych.fullerton.edu/mbirnbaum/psych466/sw/Prob_Learn/ The experiment consisted of a start-up page, warm-up page, and an experimental page. Learners entered the start-up page at the URL listed. The start-up page had a brief description of the study and instructed judges to click on their birth month, which directed them to one of the warm-up pages. The association of birth months to the between-subjects variables was counterbalanced during the course of the study. Each warm-up page was linked to its corresponding experimental page and represented one of the four Advice by Scenario conditions. Each warm-up page contained an experimental panel as shown in Figure 1 and detailed instructions (including advice in those conditions) were displayed above the panel. In addition, an abbreviated version of the instructions and advice appeared in an alert box when the judges pressed the “Start Warmup” button. The abbreviated advice is displayed in Table 1. In the no advice condition, the instruction in the alert was to “Try to predict the next 100 horse races.” After playing a warm-up game of 100 races/trials, the participants responded to three prompt boxes containing the following questions: (a) How many Effect of Instruction 8 times (out of 100) did Horse B win (0 to 100)? (b) How many races (out of 100) did you get right? (c) If you had to predict on one race, which horse do you think would win? The wording was altered appropriately for the abstract scenario. After answering these questions, learners were directed to the experimental page by clicking on a link. Insert Table 1 and Figure 1 about here. The experimental page contained the panel as in Figure 1 but without the “Start Warmup” button. Instead, an alert box automatically appeared as soon as a learner entered this page. The alert box contained the same abbreviated instructions and advice presented in the warm-up trial, with the new probability for the first game. Judges participated in five games of 100 races/trials each. Following each game, judges were presented the same three judgment questions as in the warm-up. After these questions were answered for each game, an alert box with the same instructions and advice and the new oddsmaker information appeared, initiating the new game. Although the strategy and money advice remained the same, the probability of events changed from game to game in the advice conditions. When five games were completed, participants saw a message that the experiment was finished and directed them to answer the items at the end of the page. These items included four demographic questions (age, gender, education, nation of birth) and one question asking about participant’s gambling experience. The last item asked each learner to explain his or her strategy for making predictions during the experiment. Results from experimental pages were sent by the JavaScript program that controlled the experiment to an HTML form and then to the CGI script that saved data on the server. Each person worked at his or her own pace, most completing the task within 15 min. Effect of Instruction 9 Participants Participants were directed to the Web site by “sign-up” sheets at California State University, Fullerton or were recruited through the Web and by the experimenter. Out of 171 participants, approximately half were students who participated as one option for credit toward an assignment in a lower division undergraduate psychology course. Of the 171, 49 served in the horse condition with advice, 47 served in the horse condition without advice, 40 served in the abstract condition with advice, and 35 served in the abstract condition without advice. Results Table 2 shows the mean percentage correct, averaged over five games within each condition. The table also shows what the mean percentage correct would be in each cell if the learners had probability matched and if the learners had followed the optimal strategy of always choosing the more frequent event. The highest percentage correct is observed in the horse condition with advice, the second highest value is observed in the abstract condition with advice, and the horse without advice had the lowest percentage correct. The effect of advice is significant, F(1, 164) = 16.28, but the main effect of scenario and the interaction between advice and scenario were not significant. The best average performance was observed in Game 1, but neither the main effect of Games nor any interactions with Games were statistically significant. Insert Table 2 about here. The reason that the predicted percentage correct are not exactly equal in each cell in Table 2 is that the probability of Horse B (Event R2) was randomly selected for each participant in each game, so there are slight differences among the cells in Table 2. Comparing the predicted against the obtained, one sees that the No Advice conditions had percentage correct approximately equal to that of the probability matching strategy, but the Advice conditions had Effect of Instruction 10 percentage correct significantly higher than probability matching but significantly lower than that of the optimal strategy. Dependent t-tests showed that the difference between observed and predicted by matching were not significant in the two No Advice cells, and that difference between observed and predicted based on matching was significant in both Advice cells. Differences were also tested for each game, and the conclusions were the same for each game, tested separately. Figure 2 shows how percentage of Horse B (event R2) choices varies with the true probability of the events. Filled and unfilled circles show the mean percentage of choices as a function of the underlying probability that Horse B would win (or that event R2 occurred) for advice condition and no advice condition, respectively. Probability matching implies that the means should fall on the identity line (solid line in Figure 2). The optimal strategy is to always choose the more frequent event, shown as the dashed curve in Figure 2. Data for the no advice conditions appear to fit the probability matching pattern, but data in the advice condition appear to fall in between the predictions of probability matching and the optimal strategy. Insert Figures 2 and 3 about here. Figure 3 shows the percentage correct as a function of probability, with unfilled and filled circles for no advice and advice conditions respectively. As in Figure 2, the data for no advice resemble the probability matching predictions and advice condition means fall in between the predictions of probability matching and optimal strategy. If a person had paranormal ability to predict the events, the data might fall above the predictions of the optimal policy. As shown in Figure 3, the data show no evidence of paranormal abilities. Effect of Instruction 11 Figures 4 and 5 show the percentage of participants who chose Horse B or R2 as a function of the probability of those events when asked to make one more prediction at the end of each game. These data resemble more closely the optimal strategy. Insert Figures 4 and 5 about here. To count the number of participants who appeared to follow the (nearly) optimal strategy, we counted the number of people who selected the more frequent event 95% or more of the trials. In Figure 6, the percentage of learners who used (nearly) optimal strategy is plotted against the probability of events, with unfilled and filled circles for no advice and advice conditions, respectively. At each level of probability (except .5, where strategy has no effect), more participants selected the nearly optimal strategy in the advice conditions. In both conditions, there is also a strong effect of probability. One might theorize that perhaps learners in the advice condition have a better understanding of the probabilities of events, where they have to estimate probabilities, compared to the advice group which receives correct information about the probabilities. Figure 7 shows the judged probability of Horse B (Event R2) as a function of probability, with filled and unfilled circles for advice and no advice conditions, respectively. The mean judgments show regression in both groups, compared to the identity line. However, the two groups do not appear to systematically differ in their mean judgments of probability, suggesting that the chief difference is not due to knowledge of probability, but rather to the strategy information of how to use it. SW: What are the correlations between judged and actual probability for advice and no advice conditions? Discussion Effect of Instruction 12 As in Nies’ (1962) research on a two-choice probability learning task, the present study found that telling judges probability of events increased the percentage of correct predictions. In the Nies experiment, the “randomness” of events was made explicit to some judges. Nies speculated that the “randomness” aspect of his probability task (randomly mixed marbles in a box) prevented judges from inferring that marbles would roll out in some kind of pattern. When judges believe that sequence of events have a pattern, they tend to respond in this way, which leads to suboptimal decision-making strategies, including probability matching. Perhaps some judges in the present experiment did not perceive horse races as random events and therefore were inclined to look for patterns. In fact, when judges were asked what strategy was used during the experiment, several wrote they would start each game by looking for a pattern. Some also commented that “the pattern” was hard to find, suggesting that they expected to find a pattern. Gal and Baron (1996) also found that judges do not necessarily choose or endorse the best strategy when the probability of events is given. Participants were asked to choose the best strategy for a binary learning task in which probability of events was known. Most of the participants responded that the “best” strategy is to choose the more likely event on “almost all” trials. Some participants who chose this strategy commented that when an event happens in a “streak”, the other alternative is bound to happen, and one should switch to the other alternative after such a “streak” (i.e., gambler’s fallacy). Gal and Baron also found that when occurrences of events were scattered and not in “streaks”, participants perceived the events as random and would be less likely to switch to the less likely alternative. It appears that simply knowing probability of events does not necessarily lead to the use of the optimal strategy. A problem may be that people do not perceive events in probability Effect of Instruction 13 learning tasks as independent of one another. This misconception could lead to gambler’s fallacy, pattern seeking, and probability matching. Explicitly telling participants that events are independent and random could therefore improve their performance on probability learning tasks. Because people do not always know the best strategy to use, it was predicted that telling participants to always choose the more likely event, in addition to telling them the probability of events, would elevate the number of correct predictions. The data from this experiment did not support this hypothesis. The percentage of correct predictions did not increase significantly when the strategy instruction was presented with the oddsmaker instruction. Therefore, it appears that the misconceptions previously mentioned (gambler’s fallacy, pattern seeking, and probability matching) are not completely abandoned when the optimal strategy is given to judges. The money instruction used in this experiment had a winning and losing component. Previous studies have found that losing money motivated people and led to more optimal decision-making strategies (Erev et al., 1999; Denes-Raj & Epstein, 1994). On the other hand, Arkes et al. (1986) found that judges who were not given incentives for correct judgments performed better than those who were offered incentives. It is theorized that when money (even if hypothetical) is at stake, people are less tolerant of wrong predictions and therefore are more likely to switch responses. Chau et al. (2000) also found that sequence of events was important, especially for the first few trials. People that were told the “best” strategy to use during a game of blackjack were less likely to follow the strategy if they lost on the first few trials. Some judges in the present study also appeared to base their choices on the first few trials. One judge commented that he “stuck to the first winner”, and a couple of people wrote that they based their predictions on the Effect of Instruction 14 first few trials. Therefore, sequence of events, especially for the first few trials, could affect judges’ responses to instructions. Future studies should examine this possibility. Future studies on probability learning should also examine the effect of feedback that judges’ receive. Arkes et al. (1986) found that when judges were not given feedback their performance improved because they were not receiving the negative feedback that often leads to the use of a suboptimal strategy. Assuming that people want to maximize their success, they should use available information to achieve this end. However, the problem appears to be that people do not know how to use the potentially helpful information in a probability learning task. Future studies are needed to further investigate this problem. Effect of Instruction 15 References Arkes, H. R., & Dawes, R. M. (1986). Factors influencing the use of a decision rule in a probabilistic task. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 37, 93-110. Birnbaum, M. H. (in press). Wahrscheinlichkeitslernen (probability learning). In D. Janetzko, H. A. Meyer, & M. Hildebrand (Eds.), Das expraktikum im Labor und WWW Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. An English translation can be obtained from URL: http://psych.fullerton.edu/mbirnbaum/papers/probLearn5.doc Brehmer, B., & Kuylenstierna, J. (1980). Content and consistency in probabilistic inference tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 26, 54-64. Chau, A. W. L., Phillips, J. G., & Von Baggo, K. L. (2000). Departures from sensible play in computer blackjack. The Journal of General Psychology, 127, 426-438. Denes-Raj, V., & Epstein, S. (1994). Conflict between intuitive and rational processing: When people behave against their better judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66 (5), 819-829. Erev, I., Bereby-Meyer, Y., & Roth, A. E., (1999). The effect of adding a constant to all payoffs: Experimental investigation, and implication for reinforcement learning models. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 39, 111-128. Gal, I., & Baron, J. (1996). Understanding repeated simple choices. Thinking and Reasoning, 2 (1), 81-98. Herrnstein, R. J. (1990). Behavior, reinforcement and utility. Psychological Science, 1 (4), 217-224. Nies, R. C. (1962). Effects of probable outcome information on two-choice learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64 (5), 430-433. Tversky, A. & Edwards, W. (1966). Information versus reward in binary choices. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71 (5), 680-683. Effect of Instruction Table 1 Abbreviated Instructions as They Appear in Alert Box. Content Instruction Oddsmakera Money Strategy a Horse scenario Abstract scenario Horse A should win x% and B R1 should occur x% and R2 should win y%. should occur y%. Imagine you win or lose $100 Imagine you win or lose $100 for each race you predict right for each trial you predict right or wrong. or wrong. Find the more likely horse and Find the more likely value and stick to it. stick to it. Probability of events varied from game to game and subject to subject. x = probability of Horse A or R1. y = probability of Horse B or R2. 16 Effect of Instruction Table 2. Mean Cell Percent Correct Mean Percent Correct Responses Optimal Strategy Advice No advice Horse 71.83 70.73 No horse 71.53 72.37 Mean Percent Correct Responses Actual Advice No advice Horse 68.66 63.07 No horse 66.51 62.26 Mean Percent Correct Responses Probability Matching Advice No advice Horse 62.50 61.25 No horse 62.18 63.39 17 Effect of Instruction 18 Effect of Instruction Figure Captions Figure 1. Experimental panel in warm-up page for the horse scenario. Judges made predictions by clicking on buttons, Horse A or Horse B. The box above the correct button displayed the correct event on each trial, and the panel in the center displayed “Right” or “Wrong” for 220 msec. In the abstract scenario, “R1” and “R2” replaced “Horse A” and “Horse B”. 19 Effect of Instruction Figure 2. Mean percentage of predictions as a function of the actual probability of Horse B (or R2), with open and filled circles for the no advice and advice conditions, respectively. Probability matching shown as solid line; optimal strategy shown as dashed curve. Test of Probability Matching Horse B/R2 Predictions 120 100 80 60 40 20 advice no advice optimal pm 0 -20 0 20 40 60 80 Stated Probabilities for Horse B/R2 100 20 Effect of Instruction Figure 3. Prediction of probability matching shown as solid curve; optimal strategy shown as dashed lines. Mean percentage correct for advice conditions shown as filled circles; unfilled circles show means for no advice conditions. Percent of Correct Responses as Function of Stated Probabilities 100 Mean Percent Correct 90 80 70 60 50 40 advice no advice optimal pm 30 20 10 0 0 20 40 60 80 Stated Probabilities for Horse B/R2 100 21 Effect of Instruction Figure 4. Percentage who predicted Horse B for the next trial against probability of Horse B. Prediction of Next Event: Percent of Horse B Predictions 120.00% 100.00% 80.00% 60.00% 40.00% no advice advice 20.00% 0.00% 0 20 40 60 80 Stated Probabilities for Horse B 100 22 Effect of Instruction Figure 5. Percentage of R2 predictions for the next trial against the probability of R2. Prediction of Next Event: Percent of R2 Predictions 120.00% 100.00% 80.00% 60.00% 40.00% no advice advice 20.00% 0.00% 0 20 40 60 80 Stated Probabilities for R2 100 23 Effect of Instruction Figure 6. Percentage who selected the more frequent event more than 94% of the trials. Use of Optimal Strategy as a Function of Stated Probability 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 advice 0.1 no advice 0 0 20 40 60 80 Stated Probabilities for Horse B/R2 100 24 Effect of Instruction Figure 7. Judged probability of events as a function of actual probability of events. Judged Probabilities as a Function of Stated Probabilities 90 Judged Probabilities 80 70 60 50 40 30 advice 20 no advice 10 0 0 20 40 60 80 Stated Probabilities for Horse B/R2 100 25