What is really going on in the analytic session

advertisement

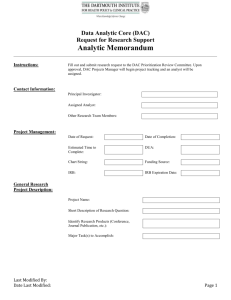

What Is Really Going on in the Analytical Session ? Eike Hinze I chose the title of my paper rather associatively and intuitively. It might invite the reader to associate freely I thought. You can think of “Finally I will know what is really going on in my parents’ bedroom.” or of Woody Allen’s movie “Everything you always wanted to know about sex but were afraid to ask.” It is a bit provocative and leaves enough space to elaborate my thoughts about the subject, I thought. But with the Summer Seminar approaching and having to write my manuscript I became more and more afraid that my choice had too much of a primary process thinking. Is it not pure megalomania to promise solving an issue like this one? And besides this there is no one-dimensional “What is really going on” in psychoanalysis because we know that every phenomenon is overdetermined and there are many ways to understand it. Let us stop here for some moments and think about how we are learning in our training what is going on in the analytic session. Every candidate has the experience of his own analysis. Then he will read Freud’s papers on psychoanalytic technique and will have seminars dealing with other authors writing about this issue. (For reasons of simplicity I always use “he” in a nongender-specific way.) He may become a bit confused and may wonder whether analysts of different theoretical orientation, belonging to different schools, conduct the same analyses. Is for example what is going on in a Kleinian analysis the same as in an analysis of the French type? He starts fantasizing about the theoretical approach of his personal analyst or wonders whether he has one at all. He starts listening to case presentations of other candidates or more experienced analysts and is amazed at the great variations in technical approach. When I remember my own training I have to admit it took me some time to make sense of these case presentations and to develop a really understanding access to the inherent process of the presented analytic material. And then one day in your training you are authorized to start your first own analysis. It is like throwing somebody into deep water who has had only a few elementary lessons in swimming. Learning by doing is the motto. You have the support of your supervisor, it is true. But again, starting your second case, you may be confronted with a surprising diversity of technical approach. Everyone may ask himself, how much space there was in his training for asking and discussing explicitly my title’s question. In my training at least the tacit assumption seemed to reign that any gifted candidate did not need to discuss this question. If he did not find the right way of analyzing this was his personal problem. Most likely his personal analysis had not yet been deep enough. I assume this was (or still is?) a widespread fantasy of candidates preventing them from asking certain questions. And there I am back at Woody Allen’s film. The diversity in technique is poignantly described by Paul Denis’ commentary to Peter Fonagy’s detailed report of an analytic session in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis (2004). He starts his commentary with: “The psychoanalytic culture to which Miss A’s analyst belongs is undoubtedly very different from that of the majority of analysts trained in France: the style of the interventions and their frequency are a long way removed from ‘the French way of analyzing’. In the majority of cases, the French analysts who are members of the IPA have adopted a technical approach that seeks to avoid a large number of lengthy and explanatory interpretations. In writing this commentary, I even found myself feeling envious of a patient who received 16 interpretations in one session – that is to say, more than I received myself in over 10 years of personal analysis.” One may object that in a single institute the variations are not so marked. But on the one hand this is presently no more granted. And on the other hand this theoretical and technical plurality is one of the greatest challenges for the scientific foundation of psychoanalysis. Moreover as PIEE-candidates you have a unique advantage –or burden- of being trained by teachers, analysts and supervisors of a larger variety as a candidate usually is confronted with. After delineating so many difficulties is there any light at the end of the tunnel? Is there any realistic chance of finding a deeper access to my topic? Following the good analytic tradition I will start with a case. CONFIDENTIAL CLINICAL MATERIAL Why did I choose this example? One reason is that I hope some of my thoughts can be demonstrated in this material. Another reason is that I recently presented this case in a group with a Kleinian supervisor. This supervision widened my view on the dynamics in this session. The patient started the session by describing an accident he had been witnessing immediately before. Two basic views on this material are possible. The patient described something that had happened outside the consulting room. It might be possible to understand how this had affected him, and perhaps one can finally connect this material with some transference manifestations and say for example: “You are afraid of developing a more personal relationship with me because then a conflict with me about your wish to be attached to me and your wish to be independent may explode and cause a clash between us like that you observed before the session.” In this view the patient tells or associates something that has happened outside, and the analyst tries to link it to other elements of his internal life. A second different view (and here I am citing David Tucked to whom I am indebted for many of my thoughts) is that the patient experiences the accident as taking place in the session. “From this perspective when associations come to the patient’s mind they can be thought of as ‘made in the room’. They are representations of experienced anxieties, impulses and sensations stimulated by lying there. They are transformed there and then into ideas, wishes and thoughts. In this model although the patient does indeed talk about incidents and happenings which have usually ‘really’ happened, they are not news items brought in from outside. They take the apparent form of news simply because what is selected works for the patient as a means to express conscious and unconscious experience in the room here and now.” (Tuckett, 2009) Analysts differ in regard to these two modalities. Looking at this session I am inclined to favor the second view. In hindsight I think that the patient talked about a clash between us which had already happened and had materialized in cancelled sessions. Not adopting this view helped me to deny the more aggressive aspects in the patient’ associations. Here a second aspect of the session becomes apparent I want to dwell on. Both, the patient and me, were engaged in a kind of enactment. The patient acted as a son striving for being seen and acknowledged by his father while at the same time defiantly fighting for independence, whereas I enacted a father who appreciated his son’s development but who tried not to experience his son’s aggressiveness in full strength. But then my final intervention contained a sadistic counter-attack. What I said can be understood as: “You may try to go away but then you will break your legs!” I am stressing here the counter-transferential aspects of this enactment because they are simply part of this session, but also because we are very often engaged in collusive enactments that we can only understand afterwards, if at all. Being engaged in enactments of various kinds is an intrinsic and essential part of our daily work as analysts. It enables us, by exploring our counter-transference, to understand better the vicissitudes of the transference and the analytic process. But we should 2 not fall into the trap of believing that we always understand our countertransference and can master it. Sometimes it needs more time than we would like to, and sometimes we need supervision. There are many analogies or metaphors describing the couple analyst/analysand. One is the interplay between mother and infant. Like all analogies it has its merits and its limitations. Another analogy I appreciate very much is that of a ballroom-dancing couple. Lichtenberg states: “from the standpoint of the observer, each (analyst and patient. E.H.) is a necessary partner in the interpersonal dance – it takes two to tango” (1989, p 297). Usually you do not see or feel your own mistakes but experience them mirrored and enlarged in your partner’s dancing. The trainer is then as indispensable as a supervisor for the analytic couple. The parallel seems striking. Very often you only get aware of your counter-transference by observing the patient’s reactions to your interventions. This is the essence of the often cited “listen to the listening” (of the patient). Picture 1 The view that an analysis consists of a chain of enactments with the analyst playing an active role in them and that every part of an analysis is happening in the consulting room is more or less shared by a great number of analysts today. In this perspective the patient’s past is coming to life in the consulting room again. But this is not the only approach to psychoanalytic technique and to “what is going on in the analytic session”. There is no authoritarian manual prescribing what really good analysis is and what not. But the analytic community has begun to study analytic processes in analyses of different analysts more deeply and across the lines drawn by so-called schools. One initiative to understand better what is going on in analyses of different analysts is the EPF Working Party on Comparative Methods (WPCCM). Groups of experienced analysts from different 3 European societies discuss case material presented by a colleague and try to find out the often implicit working models and concepts the presenter is using in his clinical work. These groups are not intended to learn more about the dynamic unconscious of analysts. This would have to be done in a different setting. But they shall –and can- explore the concepts and models we are applying in our analytic work. These models are often implicit or preconscious, and often the analyst himself is not aware of them. The way these groups are discussing is rather unusual. We are used to discuss case presentations in a supervisory mode. The group members propose a different, better or deeper understanding of the case, often transforming into a group that always knows everything better than the presenting analyst. From your training you know this type of discussion. I included the session in my paper mainly in order to discuss the way I am working. But you will certainly experience the urge to discuss it in a supervisory mode. In the CCM groups it proved to be very useful to start a discussion by trying to classify the type of the different interventions in the session (picture 1). At first sight this kind of categorizing looks a bit strange and not appropriate for a psychoanalytic approach. But discussing for some interventions the right category may sharpen the view on how this analyst is working in the session. The second step seems more interesting (picture 2) Picture 2 Working on many case presentations in the CCM groups showed that the way an analyst is working can be described in 5 axes. My case may serve as an example. My short remarks about the patient’s biography and my commenting the session demonstrated that I have some ideas on how and why his disturbance came about (What is wrong: Theory of psychopathology). These thoughts inevitably lead to my thoughts about how analysis works, that is to my transformational theory (How analysis works: Theory of psychic change). I think it is a myth that 4 there is a thing like an analysis without a tendency, without an aim. We always have some ideas about the specific psychopathology of a patient and about how change may happen. We want the patient to change and develop. Otherwise we would not start an analysis. Analysts have different ways of listening to the patient (Listening to the unconscious: Theory of the unconscious). The ideal of the evenly suspended attention may be differently realized in different analysts. Take for example the above mentioned difference between listening to the patient’s associations as describing something always originating in the consulting room or as being partly introduced from the outside. Analysts have different styles of intervening (Furthering the process: Theory of clinical technique). And analysts may have different views of the analytic situation, that is how the past comes into the present (Analytic situation: Theory of transference and repetition). The CCM approach does not give a final answer to my central question but it may help to think about it more clearly. One can better understand different styles of analyzing and can often recognize the underlying logic in seemingly purely intuitive interventions. In a way it is demystifying the analytic encounter. But again: what is psychoanalysis, what is really going on in an analytic session? The simplest answer could be: Two persons meet in a room for 50 minutes and talk to each other without any disturbance from the outside. But we share this procedure with many psychotherapists of different orientation. We have to add a specific element: a psychoanalytic theory. Two persons meet under the umbrella of a psychoanalytic theory or contained by the frame of psychoanalytic theory. Picture 3 The 5 Axes and the 3 Frames Conceptual Frame Observer Participant Frame Listening to the unconscious Furthering the process Interventional Frame 5 Picture 3 shows the importance of theory in psychoanalytic practice by visualizing it. It is a condensation of the known Three-Frames-Model and the Five-AxesScheme. I now want to introduce a seemingly simple theoretical tool, which may help to understand the dynamics of a session and which moreover may be useful in one’s daily practice. Again I owe David Tuckett the elaboration of this idea. Picture 4 Anna Freud put forward the idea that the ideal position of an analyst is a point “equidistant from the id, the ego and the superego.” Translated into everyday language this means the analyst should not love or hate the patient and neither teach nor judge him. The picture 4 shows this ideal mental position of the analyst with the black dot in the middle of the triangle. This triangle lends itself to different applications and interpretations. The analyst may think he is in this ideal centre of the triangle whereas in reality he has already moved to one of the corners. Take for example my last intervention in the session. Consciously I thought that my intervention stressed the patient’s developmental progress to a more libidinal relationship and autonomous position. I felt very much in the centre of the triangle. But unconsciously I was expressing my hate. My interpretation came more from the right lower corner. The triangle may describe the mental functioning of the patient or how the analyst views him. But there is also another triangle describing how the patient experiences the analyst. Some days ago I asked a patient to tell me more about an encounter with a difficult neighbor whereupon she became extremely furious at me. Shortly before the end of the session she could tell me that she had interpreted my question as a severe accusation. I thought I spoke from the centre of my triangle while she had put me in the extreme upper corner. The triangles, that of the patient and that of the analyst have a great heuristic value. One should always bear in mind how they interact with each other and how they are experienced from the other side. Thinking in terms of these triangles may help to preserve one’s orientation in the fire of mutual enactments. It may also help not to forget that our task is to speak about the patient and not mixing up our triangle with his. By thinking in terms of the two triangles the role of the patient comes to the foreground and his impact on the analytic encounter. The fact that this encounter is shaped by both participants, the analyst and the analysand, seems so obvious that one almost neglects that all papers about the analytic situation and psychoanalytic technique are written from the analyst’s perspective, viewed through his eyes. But if we want to know more about the analytic situation and about what is going on in analytic sessions we should also ask the patients themselves. How would they answer the question? There are only very few 6 studies or papers written from the patient’s perspective. I will draw on three more recent publications which are relevant in this context: Lora Heims Tessman’s report about interviews with analysts from her Boston Institute how they had experienced their training analyses (2003), Christine Hill’s book about interviews with former analytic patients (2010) and the results of a very thoroughly conducted catamnestic study of the German Psychoanalytic Association (Leuzinger-Bohleber, 2002). What can we learn from these studies that is relevant for our topic? First one has to overcome an objection against this kind of studies. How reliable are the accounts of former patients? Are they not imbued with transference residues, loaded with defences and neurotic distortions? This objection has to be taken seriously. And the first two mentioned books show indeed some instances of this possible bias. But it is not a sufficient reason for dismissing the reports of former patients at all. The catamnestic study showed that after successful analyses memories and general evaluation showed a striking similarity between analyst and former patient. One interesting finding was that the analyst’s theoretical orientation was not decisive for the patient’s satisfaction with the analysis and the outcome. But this does not contradict my previous statement that theory plays such an important role in the analytic session. The catamnestic study showed that a professional attitude – and this includes being able to link theory with clinical practice – was an essential factor in promoting a patient’s satisfaction with his analysis and a favorable outcome. Flexibility and the ability to attune very personally and specifically to the patient were other decisive factors. For the patients’ satisfaction it was of utmost importance that an emotional match between him and the analyst existed and that the latter invited him to participate as an active partner in the analytic process. The emotional match was not simply a question of mutual sympathy but a complex process of emotional attunement. And it was striking that most patients were able to differentiate between an analyst who was only nice and friendly and an analyst whose professional stance was part of a dedicated human attitude. An analyst was seen as contra-productive if he knew everything in advance and behaved as a keeper of the truth. Hinshelwood (1997, p 105) once commented humorously: “If the psychoanalyst’s aim is that the patient should know his/her own mind better than before the analysis, can that be achieved by the analyst knowing better what the patient should think and decide? If the psychoanalyst knows for the patient, does this in the long run contribute to the patient knowing better for him/herself? It becomes a paradox.” What we can learn from all these findings is that in an analysis we are not the experts who know everything about a patient’s unconscious. He needs to be taken seriously in his conscious experience and has to be invited to actively take part in a shared journey to explore the denied and disclaimed parts of his mind. I am slowly coming to the end of my paper. I apologize for not having given you a comprehensive answer to the question what is really going on in the analytic session. But I hope having invited you to think more courageously about this question and not to be stuck in scholastic thinking of whatever kind. In a world, where pluralism is progressively infiltrating many domains of social life, pluralism in psychoanalysis is at the same time an exciting challenge and a danger for our existence. We need you as the next generation of analysts to come to grips with these problems and questions. But I do not want to finish my presentation with such solemn words. At the end I want to tell you a funnier story about my participation in a CCM group as a presenter. In a session I presented an unfamiliar noise could be heard at the beginning. The water flushing of my toilet beside my consulting room was broken and was running for a very long time. My patient asked for the reason of this noise. And I bluntly answered that my water toilet was broken. The group burst into laughter sensing my acting out of a counter-transference reaction. They were 7 right. At that moment I did not realize the unconscious use the patient made of this incident. Later on I started to think about different possible interpretations various analysts might have given in this moment. Giving an interpretation is always an active choice between different options. Analyst A might have interpreted links the patient had made between the noise and unconscious anxieties. Analyst B might have understood the patient’s question as an expression of an unconscious scene he was creating in that very moment. Analyst C might have thought that first he had to validate the realistic observation of the patient before going on to interpret unconscious material. Analyst D might have stayed silent waiting for the patient to unfold his representational world without paying much attention to transference and counter-transference. Analyst E might have reacted like me, but with focusing on attachment theory in the back of his mind. Before reaching analyst Z I will stop here. But a multitude of possible interpretations is appearing. And with this confusing multitude I end my presentation. References Denis, P (2004): Commentary to Miss A (Fonagy). Int J Psychoanal, 85, 814-816. Freud, A (1937): The Ego and the Id. Heims Tessman, L. (2003): The analyst’s analyst within. The Analytic Press, London. Hill, A.S.CH. (2010): What do patients want? Psychoanalytic perspectives from the couch. Karnac, London. Hinshelwood, R.D. (1997): Therapy or Coercion? Does Psychoanalysis differ from brainwashing? Karnac, London. Leuzinger-Bohleber, M (2002): “Forschen und Heilen” in der Psychoanalyse. Ergebnisse und Berichte aus Forschung und Praxis. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. Lichtenberg, J (1989): Psychoanalysis and Motivation. Hillsdale NJ, The Analytic Press. Tuckett, D (2009): Inside and outside the window: Some fundamental elements in the theory of psychoanalytic technique. Paper read in London, not yet published. 8