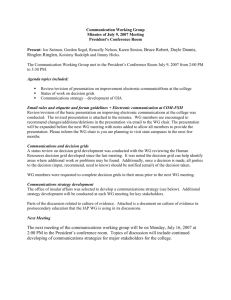

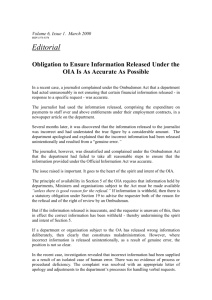

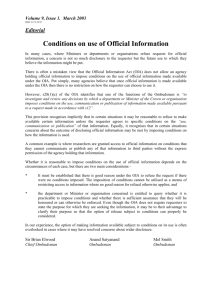

DOC - Office of the Ombudsman

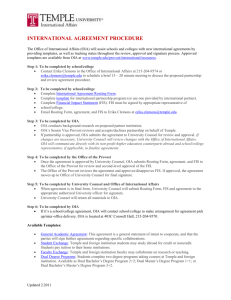

advertisement