Integrative Model of Rumination

advertisement

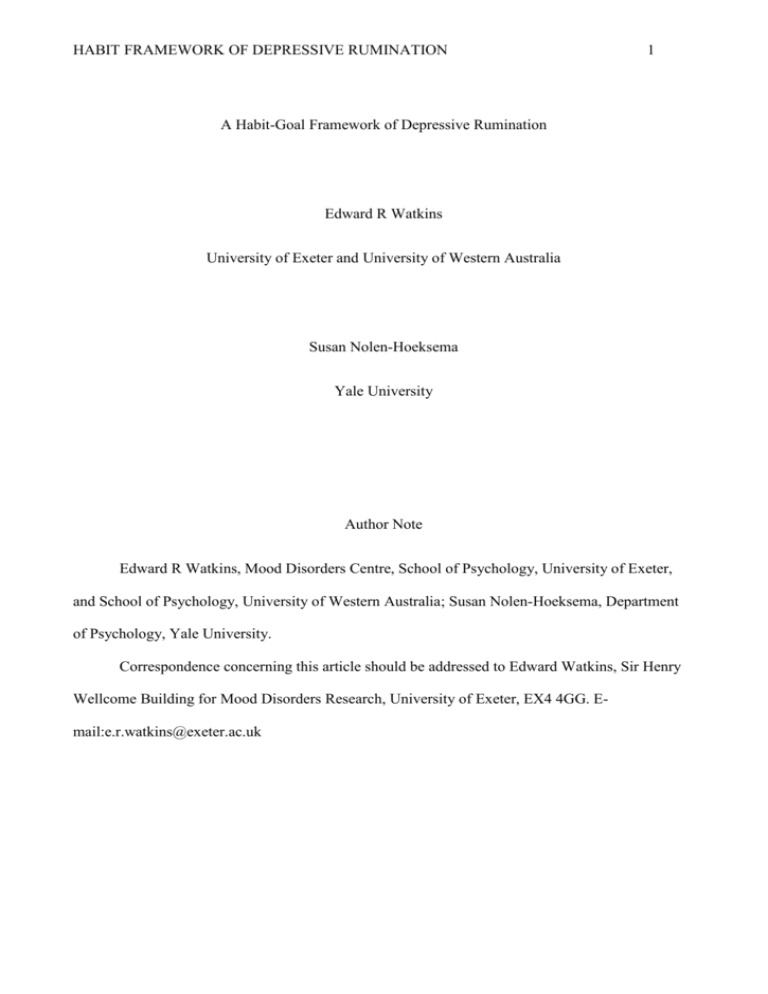

HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 1 A Habit-Goal Framework of Depressive Rumination Edward R Watkins University of Exeter and University of Western Australia Susan Nolen-Hoeksema Yale University Author Note Edward R Watkins, Mood Disorders Centre, School of Psychology, University of Exeter, and School of Psychology, University of Western Australia; Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, Department of Psychology, Yale University. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Edward Watkins, Sir Henry Wellcome Building for Mood Disorders Research, University of Exeter, EX4 4GG. Email:e.r.watkins@exeter.ac.uk HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 2 Abstract Rumination has been robustly implicated in the onset and maintenance of depression. However, despite empirically well-supported theories of the consequences of trait rumination (Response Styles Theory; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) and of the processes underlying state episodes of goal-oriented repetitive thought (Control Theory; Martin & Tesser, 1989, 1996), the relationship between these theories remains unresolved. Further, less theoretical and clinical attention has been paid to the maintenance and treatment of trait depressive rumination. We propose that conceptualizing rumination as a mental habit (Hertel, 2004) helps to address these issues. Elaborating on this account, we propose a framework linking the Response Styles and Control Theories via a theoretical approach to the relationship between habits and goals (Wood & Neal, 2007). In this model, with repetition in the same context, episodes of self-focused repetitive thought triggered by goal discrepancies can become habitual, through a process of automatic association between the behavioral response (i.e., repetitive thinking) and any context that occurs repeatedly with performance of the behavior (e.g., physical location, mood), and where the repetitive thought is contingent on the stimulus context. When the contingent response involves a passive focus on negative content and abstract construal, the habit of depressive rumination is acquired. Such habitual rumination is cued by context independent of goals, and resistant to change. This habit framework has clear treatment implications and generates novel testable predictions. Keywords: rumination, control theory, response styles, goal, habit, abstract HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 3 A Habit-Goal Framework of Depressive Rumination Depressive rumination is the tendency to repetitively analyze oneself and one’s problems, concerns, and feelings of distress and depressed mood (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Watkins, 2008). Prospective longitudinal and experimental studies have implicated depressive rumination in the onset and maintenance of symptoms and diagnosis of major depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008; Watkins, 2008), as well as anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and substance/alcohol abuse, leading to the hypothesis that it is a transdiagnostic pathological process (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004; Ehring & Watkins, 2008; NolenHoeksema & Watkins, 2011). The principal theory concerning depressive rumination is the Responses Styles Theory (RST; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), which hypothesizes that depressive rumination is a stable, enduring, and habitual trait-like tendency to engage in repetitive self-focus in response to depressed mood (see Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). RST argues that depressive rumination leads to depression by enhancing negative mood-congruent thinking, impairing problem-solving, and interfering with instrumental behavior, with these mechanisms confirmed in experimental studies (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). A distinct alternative view of rumination is provided by Control Theory accounts, which define it as “a class of conscious thoughts that revolve around a common instrumental theme and that recur in the absence of immediate environmental demands requiring the thoughts” (Martin & Tesser, 1996, p.7). This account explains the conditions leading to state episodes of ruminative thought. It hypothesizes that state rumination is initiated by and focused on a perceived discrepancy between one’s goals and one’s current state and continues until the goal is either attained or abandoned (Martin & Tesser, 1989, 1996). Unlike RST, this account encompasses both normal and constructive versus abnormal and unconstructive forms of repetitive thought: goal-oriented rumination can be helpful if focus on the unresolved goal facilitates progress, but unhelpful if it HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 4 only serves to increase salience of the discrepancy. Consistent findings confirm that unattained personally important goals predict repetitive thought in real-world studies (see Watkins, 2008). Watkins (2008) examined what processes determine whether repetitive thought has unconstructive versus constructive consequences. During rumination, negative thought content, negative context (e.g., negative mood), and abstract-evaluative thinking focused on the meaning and implications of negative events (e.g., asking “Why?”) relative to concrete thinking focused on the details, process, and context of negative events (e.g., asking “How?”), contribute to unconstructive outcomes. In Control Theory, goals, events, and actions can be represented at different levels of abstraction within a hierarchy ranging from abstract representations capturing their decontextualized gist and characterizing why they occurred or are performed, down to concrete representations of their contextual and situational details characterizing how they occurred or are to be performed. Effective self-regulation requires flexible movement through the hierarchy to match circumstances. Overly abstract processing of negative information was hypothesized and found to be unhelpful because it increases the personal importance of events and exacerbates emotional reactivity (Watkins, Moberly & Moulds, 2008) and impairs problem-solving by limiting the availability of detailed alternative plans (Watkins & Moulds, 2005). This elaborated Control Theory account (Watkins, 2008) provides a partial reconciliation between RST and Control Theory because it identifies abstract-evaluative thinking focused on negative content as pathological, consistent with the RST characterisation of depressive rumination as focusing on the causes and implications of depressive mood. Despite the successes of these theories, key questions such as “What are the developmental antecedents of individual differences in rumination?” and “What makes it so difficult to break free of rumination once it has begun?” remain unanswered (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008, p. 418). Moreover, the relationship between state episodes of goal-oriented repetitive thought and the trait tendency towards depressive rumination is unresolved. Are they separate and distinct processes? Or HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 5 do some individuals transition from state episodes of goal-oriented rumination into more habitual depressive rumination? A major but relatively unelaborated implication within RST is that depressive rumination is a habitual cognitive response to negative mood (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). We propose that more explicitly considering rumination as a mental habit (see Hertel, 2004) has value in generating potential insights and testable hypotheses relevant to these issues. Habits are behaviors that are performed frequently in stable contexts (Ji & Wood, 2007). In classical conditioning and learning theory (e.g., Hull, 1943), habits are learned behavioral responses to situational cues that have become established through a history of systematic repetition and reinforcement. A stimulusresponse (S-R) habit is learnt when a particular behavioral response is contingent on the stimulus (Dickinson, 1985; Mackintosh, 1983; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972). For example, with overtraining or training with interval schedules of reward contingency, animals learn to perform a response habitually to set cues, even when the reward is devalued, for example, by making animals mildly ill with a lithium chloride injection after consuming sucrose pellets (Dickinson, 1985). Wood and Neal (2007, p. 843) defined habits as “learned dispositions to repeat past responses. They are triggered by features of the context that have covaried frequently with past performance, including performance locations, preceding actions in a sequence, and particular people.” Habitual behavior typically involves some automaticity (Verplanken, 2006; Verplanken & Orbell, 2003; Wood, Tam, & Guerrero Witt, 2005). A behavior can be conceptualized as automatic on several distinct dimensions: lack of conscious awareness, not requiring extensive resources to be performed (e.g., performed equally well under cognitive load versus not under load), lack of control, and lack of conscious intent (Bargh, 1994). Verplanken, Friborg, Wang, Trafimov, and Woolf (2007, p. 526) proposed that a habit is “a behavior that has a history of repetition, is characterized by a lack of awareness and conscious intent, is mentally efficient, and is sometimes difficult to control.” HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 6 As a response that occurs frequently, unintentionally, and repetitively to the same emotional context (depressed mood), depressive rumination fulfils all of these conceptualizations of habit. Its gold standard measure, the Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), assesses the frequency of repeated ruminative behaviors in response to the stable internal context of feeling sad, down, or depressed. Depressive ruminators report that rumination occurs without conscious intent, and that they are unable to control it (Watkins & Baracaia, 2001). A self-reported index of habitual negative thinking capturing frequency, lack of conscious awareness, lack of conscious intent, mental efficiency, and difficulty in control, was positively correlated with both trait and state rumination (Verplanken et al., 2007). More explicitly, Hertel (2004) hypothesizes that rumination is a habit of thought, noting that the initiation of an episode of rumination often occurs automatically, without conscious awareness or effort. Hertel argues that impairments in cognitive control may enable the emergence of such mental habits. Situations in which stimulus and task dimensions do not inherently constrain and guide attention (e.g., tasks with lax external control) afford habitual rumination in patients with depression (Hertel, 1998) whereas situations constrained to force participants to sustain attention on particular task stimuli do not (Hertel & Rude, 1991). Outlining an argument further developed here, Hertel (2004, p. 208) proposes that “the best antidote to maladaptive habits is a new set of habits” formed through repeated practice at more controlled responses. In this paper, we focus on analysing depressive rumination as a habit, consistent with Hertel (2004), whilst adding Wood and Neal’s (2007) empirically-supported theoretical framework. We propose that applying this habit-goal framework provides a means to understand the relationship between trait depressive rumination (RST) and goal-oriented state repetitive thought (Control Theory), helps to explain why rumination may be hard to change, and suggests novel therapeutic implications and testable predictions. A Habit-Goal Framework of Depressive Rumination HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 7 Wood and Neal (2007) argue that repeated performance of a behavior in a consistent context can lead to the development of habitual responding via (1) associative learning and (2) instrumental learning. They identify three interrelated principles that summarize the development and performance of habits: (1) habits are cued by context; (2) habit context-response associations are not mediated by goals; (3) since habits are acquired slowly with experience, they are inherently conservative and tend to persist even in the face of antagonistic current goals or intentional behavior. These principles reflect properties within conditioning models (Mackintosh, 1983; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972), in which (1) habits are acquired when responses are contingent on stimulus contexts; (2) S-R habit strength is not mediated by goals; (3) Because habits are acquired slowly, they extinguish or counter-condition slowly. We propose that these principles provide a useful framework to consider how the consequences of habits may play out in depressive rumination, with implications for understanding and treating depressive rumination. First Principle: Habits are Directly Cued by Context as a Result of Frequent Covariation of the Behaviour with the Cueing Context. Wood and Neal (2007, p. 844) propose that “habits typically are the residue of past goal pursuit: they arise when people repeatedly use a particular behavioral means in particular contexts to pursue their goals”. Such context cues become automatic triggers for the behavioral response, such that the behavior is controlled by the presence or absence of the cue, rather than mediated by an implicit or explicit goal. Thus, a goal-based response that occurs frequently and contingently to a particular context could result in the development of a habitual response to that context, consistent with classic stimulus-response (S-R) theories of learning (Mackintosh, 1983). Context includes physical setting (e.g., bedroom), time of day, the people (e.g., alone), behaviors performed prior to, and internal state (e.g., mood, fatigue, Ji & Wood, 2007), and any combination thereof, in which the behavior typically occurs. The formation of associative links between the habitual response and a potential cueing context requires the repeated co-activation of the mental representations of both response and HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 8 context, as a consequence of contingent pairings between the response and the cueing context across multiple episodes in the environment. The learning of a habit (S-R association) requires the context and the response to occur close together in time (temporal contiguity), and for the potential habitual response (e.g., rumination) to be contingent on the stimulus context. With repetition across multiple episodes, incremental changes are hypothesized to occur in procedural memory, such that the common features of response and context become learnt and encoded (Gupta & Cohen, 2002). Importantly, multiple different behaviors occurring to a particular context will weaken any reliable co-variation and contingency between any one particular habitual behavior and the contextual cue: “the greater the numbers of behaviors linked to a given context, the lesser the capacity for the context to cue any one behavior directly” (Wood & Neal, 2007, p.858). Implications for Depressive Rumination This habit-goal framework suggests that depressive rumination will become a habitual trait if state episodes of ruminative thought are contingent on the context of negative mood, such that the negative mood state becomes an automatic cue for ruminative thought. This account provides a mechanism by which state episodes of repetitive thought initiated by goal-discrepancy (consistent with Control Theory) can become habitual if such thinking is contingent on a co-occurring context (negative affect) (consistent with RST). With respect to goal-discrepancy accounts of rumination (Martin & Tesser, 1989, 1996; Watkins, 2008), the identification of an unresolved goal (or of insufficient goal progress) can directly generate repetitive thought as a function of increased priming and accessibility of goal-relevant information, and the perseverance of goal-related thoughts (Brunstein & Gollwitzer, 1996; Goschke & Kuhl, 1993; Martin & Tesser, 1989; Zeigarnik, 1938). Control theory accounts (Carver & Scheier, 1982) and goal models of emotion (Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987) also predict that insufficient goal progress can generate negative affect (e.g., perceived loss of valued goal produces sadness). These dual effects of unresolved goals afford the opportunity for sad mood (or other mood states) to co-occur with repetitive thought, making it a HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 9 potential mechanism for developing habitual repetitive thought. Building on Wood and Neal (2007), this goal-habit framework suggests that habitual rumination can emerge as an unintended residue of goal-oriented repetitive thought. However, the repetitive thought produced by unresolved goals is not necessarily pathological: as noted earlier, goal-oriented repetitive thought can be constructive (Watkins, 2008). Thus, the habit of pathological depressive rumination would only develop under conditions where the form of state repetitive thought contingent on a stable context (e.g., depressed mood) was predominantly passive, negative, and abstract. If over time, an individual used a range of different behaviors (e.g., distraction, abstract thought) in response to unresolved goals and associated negative mood, there may be no distinct contingency between context and response, and no particular habit would develop. Conversely, the repeated use of concrete action-oriented thinking in the face of goal-discrepancy might buffer against the development of unhelpful rumination-as-ahabit (Watkins, 2008), instead forming a helpful habit of problem-solving to sad mood. Thus, the co-occurrence of episodes of goal-discrepancy rumination and negative mood is insufficient to result in trait depressive rumination, explaining why many people can experience occasional episodes of negative rumination without necessarily developing depressive-rumination-as-a-habit. This habit-goal framework suggests hypotheses about the developmental antecedents of individual differences in depressive rumination. The formation of habitual depressive rumination is hypothesized to involve two background conditions: (1) Environments and situations that generate repeated and frequent episodes of goal-discrepancy repetitive thought contiguous and contingent with negative mood (and other contextual cues, e.g., behavior of others; locations), such as the experience of having hard-to-abandon personally important goals chronically thwarted (e.g., chronic stress, abuse, or trauma); (2) A restricted repertoire of coping behaviors and/or reduced flexibility in selecting behaviors within this repertoire, constraining individuals towards passive and abstract responses, which increases the likelihood of unhelpful episodes of repetitive thought becoming contingent to negative mood. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 10 To date, these background conditions have tended to be studied in isolation. A novel prediction from this framework is that the effect of one background condition on the formation of rumination-as-a-habit will be moderated by the presence or absence of the other condition. Being in an ongoing difficult situation will not necessarily lead to habitual depressive rumination: Ongoing difficulties may lead to episodes of state rumination as a normal and often adaptive response to unresolved goals but this will not result in habitual depressive rumination unless unhelpful episodes of repetitive thought are contingent on the associated context (e.g., sad mood), which will be facilitated by a reduced range of coping options. Conversely, having a tendency towards abstract processing or passive responses will not necessarily lead to habitual depressive rumination, unless there are ongoing unresolved goals that afford the opportunity for repeated episodes of repetitive thought in a co-occurring context, leading to repetitive thought being contingent on negative mood. Of course, some circumstances may simultaneously produce both conditions (e.g., neglect, abuse), and are thus significant risk factors for habitual rumination. Consistent with exposure to chronically unresolved goals acting as a setting condition, trait depressive rumination is associated with history of sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and assault, which reflect situations in which major personal goals of safety, affiliation, and sense-making tend to be chronically unresolved (e.g., Conway, Mendelson, Giannopoulos, Csank, & Holm, 2004; Spasojevic & Alloy, 2002). Further, ongoing chronic stress and reduced sense of mastery in women predicted increases in trait rumination over time (Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999). This account hypothesizes that developmental circumstances and socialization processes that encourage limited and passive responding increase the likelihood of developing habitual rumination. Such circumstances include overcontrolling parenting, reduced positive reinforcement, and socialization into the stereotypically feminine gender role identity. Operant conditioning approaches hypothesize that when active responses repeatedly fail to receive sufficient positive reinforcement, the contingency learnt is that there is no value in being active, leading to a reduced behavioral repertoire and increased passive responding (Ferster, 1973). HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 11 Thus, any environment characterized by reduced positive reinforcement is hypothesized to engender the development of passive responding. Mothers who did not explicitly encourage their 5-7 year old children to try different approaches and who told the child what to do, had children who become more helpless, passive, and poorer at active problem-solving when faced with an upsetting and frustrating situation (Nolen-Hoeksema, Mumme, Wolfson, & Guskin, 1995). Consistent with such parenting being associated with habitual rumination, in a retrospective design Spasojević and Alloy (2002) found that undergraduates who reported over-controlling parenting during their childhood reported increased trait rumination, after controlling for levels of psychopathology. Further, in a multi-wave prospective study, Gaté et al. (2012) found that laboratory observation of reduced positive maternal behavior (indexed by frequency of happy, pleasant, or caring affect, and approving, validating, affectionate, or humorous statements) when discussing and planning a pleasant event with the child at age 12 prospectively predicted trait depressive rumination in the child at age 15, but only in girls. Thus, fewer validating and caring responses from mothers to daughters when jointly planning a pleasant event predicted later rumination. This gender effect is consistent with the commonly found gender difference in the expression of rumination, with rumination more frequent in girls and women than boys and men (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999), with this gender difference emerging in early adolescence (ages 12-13; Jose & Brown, 2008). This gender difference in rumination may partially reflect developmental differences in the socialization into gender role identities. The stereotypically feminine gender role identity emphasises greater focus on emotions and passivity. Therefore, socialization into this gender role is hypothesized to increase the likelihood of developing rumination-as-a-habit. Consistent with this, in a prospective longitudinal study, Broderick and Korteland (2004) found that 9-12 year old school children strongly identifying with the feminine role identity reported significantly more trait rumination at follow-up, regardless of gender. Cox, Mezulis and Hyde (2010) found that greater feminine gender role identity amongst children at age 11 and maternal encouragement of emotion expression in response to the child completing a difficult math task each separately mediated the HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 12 relationship between child gender and the development of trait depressive rumination at age 15, after controlling for trait rumination at age 11. An abstract style of responding to difficulties is also implicated in impaired problem-solving and reduced action orientation (Watkins, 2008). In healthy individuals, there appears to be flexibility and contextual variability in the use of abstract versus concrete processing, with individuals adopting abstract processing as a default mode, particularly when in positive mood, but switching towards concrete processing in response to difficulties and sad mood (Beukeboom & Semin, 2005; Watkins, 2011). This flexibility in regulating processing mode to different contexts is hypothesized to be functional, with concrete processing aiding problem-solving, and thus adaptive for difficult situations, whereas abstract processing aids longer-term planning, generalization, and consistency and stability of behavior towards long-term goals across time and situations, and is thus adaptive when things are going well. There are individual differences in the tendency and/or ability to regulate processing mode to context, with depressed patients impaired at becoming more concrete in response to sad mood relative to healthy controls (Watkins, 2011; Watkins, Moberly, & Moulds, 2011). We hypothesize that these individual differences influence the formation of habitual depressive rumination: Impaired regulation of processing mode reduces flexibility in responding and increases the likelihood of episodes of repetitive thought being unhelpful, providing circumstances for such thinking to become contingent on low mood. Such dysregulation of processing mode could reflect deficits in cognitive control: Individuals with deficits in executive/inhibitory control, either because of greater cognitive load or reduced cognitive resources, may be impaired at effectively regulating processing in response to situational demands (Watkins, 2011). Dysregulation of processing mode could also be the consequence of past developmental learning and parenting style. Praising or criticising a child generically (i.e., as a person, “You are a good boy”), rather than giving feedback on the specific process and concrete behaviour (e.g., “You came up with a good solution”) can lead children to HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 13 think in abstract trait terms (for both positive and negative events), leading to helplessness in response to later mistakes (Cimpian, Arce, Markman, & Dweck, 2007; Kamins & Dweak, 1999). The hypothesized relationship between habitual depressive rumination and a restricted coping repertoire is probably bi-directional. As well as a reduced range of coping strategies increasing the chance of episodes of unhelpful repetitive thought becoming contingent on negative mood, habitual rumination may also reduce flexibility in selecting coping strategies. Rumination mediates the relationship between induced negative affect and working memory capacity (Curci, Lanciano, Soleti, & Rimé, 2013) and causally reduces central executive functioning (Watkins & Brown, 2002), which are implicated in flexible responding. Second Principle: Habit Context-response Associations are not Mediated by Goals. Wood and Neal (2007) suggest that the habitual response is then activated by the perception of the cues in the context where the behavior has been repeatedly performed, such that the habit is performed without mediation by a goal. Supporting this account, contexts but not goals automatically trigger overt habit performance (Ji & Wood, 2007; Neal, Wood, Labrecque, & Lally, 2012). For strong habits, attitudes and intentions have limited predictive power on behavior, whereas one index of habit strength (operationalized by combining frequency and stability of behavior to the same context) predicts how much people repeat behaviour, even in the absence of an explicit supporting goal (Ji & Wood, 2007; Neal et al., 2012; Ouellette & Wood, 1998). Implications for Depressive Rumination The goal-habit framework suggests that depressive rumination would be triggered by the relevant cueing context (e.g. negative mood) in the absence of a personally important unresolved goal or of an intention to think about the related concern. The habit being directly cued by context means that depressive rumination can occur without direct intention and without effort. Once the habit is formed, rumination can still occur even if the unresolved goals that originally triggered episodes of state repetitive thought have been attained or abandoned. Moreover, negative mood states induced by processes other than a perceived goal discrepancy, such as direct HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 14 physical/biological effects (e.g., effect of weather, pharmacological agent) or direct responses to stimuli (e.g., empathic response to another’s distress, watching a sad movie) could then trigger rumination, extending the range of situations cueing this response. This principle could be tested by adapting the methodologies used by Ouellette and Wood (1998) and Neal et al., (2012) in which habit strength, context, explicit goals, self-efficacy, attitudes and beliefs are examined as prospective predictors of the repeated behavior (episodes of depressive rumination). Habit strength is hypothesized to predict subsequent ruminative behavior, as assessed by diary or experience sampling methods, over and above motivational and belief variables. Motivated Cueing and Instrumental Learning In addition to associative learning, Wood and Neal (2007, p. 846) propose that “habit associations may also arise through a process in which the reward value of response outcomes (e.g., positive affect from eating popcorn) is conditioned onto context cues (e.g., movie theater) that have historically accompanied the receipt of those rewards. This analysis builds on instrumental learning theories in which habits develop as organisms learn context-response associations in order to obtain rewarding events.” In this process of motivated cueing, given sufficient repetitions, the reward associated with a response is conditioned on the contextual cue, such that the cue then motivates the response by activating a desire or urge towards the response as an opportunity to acquire the associated reward. Because depressive rumination has such clear negative consequences, it is not obvious what potential reward value or instrumental function it may have. Nonetheless, motivated cueing could potentially cement the strength of the habit if robust reinforcing functions for rumination exist. Rumination has been hypothesized to act as avoidance that is negatively reinforced by reducing distress. Martell, Addis, and Jacobson (2001, p.121) proposed that “although rumination may be experienced as aversive to the individual, it is possible that it is maintained by the avoidance of even more aversive conditions.” Rumination may put off overt action and avoid the risk of actual failure and humiliation, or serve to avoid unwanted personal characteristics (e.g., becoming selfish) HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 15 through constant vigilance and criticism of one’s performance. Nolen-Hoeksema et al., (2008) hypothesized that rumination is reinforced by the reductions in distress that come from withdrawing from aversive situations and from being relieved of responsibility for outcomes. Although trait rumination is correlated with avoidance (e.g., Giorgio et al., 2010), this is not direct evidence that rumination has an avoidant function. Rumination may also have perceived positive reward value as a means to increase understanding and insight into self, feelings, and problems and to make sense of difficulties (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1993; Watkins & Baracaia, 2001). Believing that rumination increases understanding predicts the maintenance of trait rumination over 8 weeks prospectively (Kingston, Watkins, & O’Mahen, in prep), whilst experimentally manipulating appraisals that rumination is helpful versus unhelpful for understanding problems causally influenced state rumination occurring to a subsequent failure task (Kingston, Watkins, & Nolen-Hoeksema, in prep). However, there is no direct experimental evidence of whether depressive rumination has any reinforcing qualities and whether they consolidate it as a habit. Testing this functional hypothesis is challenging: Each individual may have his or her own idiosyncratic function(s) for rumination, making it hard to detect the effects of manipulating rumination on functional outcomes within standardised experimental conditions. Experimental studies also need to ensure that the functionunder-test is of value to the participant. For example, there is no point in testing for an avoidant function unless the study design exposes the participant to a sufficiently negative experience that it is meaningful and motivating for the participant to avoid. Kingston, Watkins and Nolen-Hoeksema (submitted) exposed undergraduates to the challenging situation of believing they had to be assertive to a friend or family member about a difficult issue, before randomising them to ruminating about this situation versus thinking over the situation in a non-ruminative way, and assessed various indices of avoidance as dependent variables. Consistent with Nolen-Hoeksema et al., (2008) hypothesis, rumination increased justification for avoidance by reducing sense of HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 16 responsibility and increasing certainty that efforts would be fruitless, relative to the control condition. This design only tested whether manipulating rumination influences outcomes that enable inference about function. A necessary further stage to test the functional hypothesis is to examine whether such inferred functions increase the use of rumination. One potential next step is to test whether individual differences in the effect of manipulated rumination on justification for avoidance prospectively predicts trait rumination. Third Principle: Because Habits are Acquired Slowly with Experience, They are Conservative and Do Not Alter in Response to Current Goals or Infrequent Counter-Habitual Responses. Wood and Neal (2007, p.844) argue that “habits arise from context-response learning that is acquired slowly with experience. As a result, habit dispositions do not alter in response to people’s current goals or occasional counter-habitual responses. Thus, habits possess conservative features that constrain their relation with goals.” Hertel (2004, p.208) noted that “habits of thought are difficult to oppose.” Habits are insensitive and resistant to changes in goals, outcomes, and intentions, including the devaluing of outcomes (Dickinson, 1985). Because control of a habitual behavior is outsourced directly to those contextual cues that have been reliably paired with past enactment of the behavior, habits are enacted and performed without reference to goals or outcomes. Because a habitual behavior is not especially sensitive to either outcomes or goals, it continues to be performed even if it has unhelpful outcomes. Further, because automatic cueing of behavior in response to contextual cues is likely to be more immediately available and require less executive capacity than more deliberate and thoughtful actions, it will tend to take precedence over intentional behaviors. Thus, when in conflict with habits, goals have little impact on actual behaviour. Similarly, when goals are in concert with habits and both dictate the same response, goals effectively become epiphenomena. Implications for Depressive Rumination HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 17 This analysis suggests that once rumination becomes a habit, it will be hard to stop even if new behavioral goals are adopted, even if it has negative consequences, or even if the rumination is at odds with an individual’s attitudes and intentions. This is consistent with the phenomenological quality reported by patients of “not being able to help” ruminating (Watkins & Baracaia, 2001). Intentions to stop ruminating alone are unlikely to be successful and habitual rumination will be resistant to change. The goal-habit framework thus provides a partial explanation of why patients find it so difficult to break free of rumination once it has begun, even when they recognise it has negative consequences. Implications for the Treatment of Depressive Rumination This framework offers a fresh approach to considering interventions for depressive rumination when allied with the literature on successful habit change. It suggests, for the reasons noted above, that interventions focused on changing individual’s beliefs, attitudes, and intentions and providing new information are unlikely to be effective at changing habitual behaviors, as empirically confirmed by Verplanken and Wood (2006) and Webb and Sheeran (2006). Changing goals, persuasion, cognitive restructuring, or psycho-education is thus hypothesized to be less effective at changing depressive rumination. Although trait rumination has not been frequently examined in randomized controlled trials of psychological interventions, the few extant studies suggest that rumination does not change significantly in response to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (Schmaling, Dimidjian, Katon, & Sullivan, 2006) or that elevated rumination predicts worse outcomes to CBT (Jones, Siegle, & Thase, 2007). We hypothesize that the more rumination is a strong (versus weak) habit, the harder it will be for patients to stop, and the less successful information-based interventions will be (Webb & Sheeran, 2006). Instead, Wood and Neal (2007, p.860) propose that “interventions to maximize habit change provide people with concrete tools for controlling habit cueing”. The current framework suggests that habits can be broken by altering or avoiding exposure to the cues that trigger habit performance (Verplanken & Wood, 2006). Removing contextual cues could occur as a consequence of deliberate HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 18 attempts to control cue exposure, which may require ongoing and sustained effortful control to identify and avoid relevant cues, or from unplanned changes that occur naturally as a consequence of life events, such as moving house or changing job. Wood, Tam, and Guerrero Witt (2005) found that when the location or environment associated with a habitual behavior (e.g., TV watching) changed when students transferred to a new university, the behavior became less habitual. Hence, this framework suggests that one way to reduce depressive rumination is to alter or reduce exposure to its triggering context. Where the cueing context for rumination involves a particular location (e.g., bedroom), person, preceding behavior (e.g., sitting down for a coffee after work) or environmental feature (e.g., sad music), environmental modification to remove or avoid the triggering context is hypothesized to interrupt depressive rumination. One context identified by Hertel (1998; 2004) is situations that lack external control over attention and that therefore afford mind-wandering. Habitual rumination is more likely to occur when the current activity or task does not externally constrain attentional focus. Habitual rumination will be triggered during tasks that are open-ended, unstructured, and rely on self-control, and when an individual has an “empty” unplanned period of time, such as lying in bed doing nothing. Introducing more structure and constraints into activities may change the context to reduce the triggering of habitual rumination. A long-term reduction in rumination is possible if contextual cues can be permanently removed or consistently avoided. However, this strategy is dependent on individuals being able to accurately identify cues for habits, requiring a detailed functional and contextual analysis to determine the triggering cues for rumination, although this may not always be successful. Consistent with this hypothesis, an intervention incorporating functional analysis and stimulus control (Rumination-focused CBT; Watkins et al., 2007, utilising behavioral activation principles, Martell et al., 2001) successfully reduced depression and rumination (Watkins et al., 2011) in a randomised controlled trial. However, this treatment had multiple components and the effectiveness of stimulus control has not been tested as a separate intervention. This framework predicts that HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 19 stimulus control alone will reduce trait depressive rumination when there are identifiable environmental cues tractable to modification. However, when the cueing context is an internal state, such as a negative mood, as typical for depressive rumination, it is less straightforward to permanently alter or avoid the context. This framework predicts that reducing the negative mood would, at least temporarily, reduce the enactment of the depressive rumination habit. This framework predicts that any intervention that reduces negative mood, whether antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, distraction, or change in circumstances, would reduce the expression of habitual rumination by removing one cue that triggers the ruminative habit. Consistent with this, self-reported trait rumination reduces as acute symptoms of depression diminish (Roberts, Gilboa & Gotlib, 1998). However, a key implication of this framework is that removing the context does not change the context-response association underlying the habit but only limits its expression. On any subsequent return of the triggering context, such as another period of sad or depressed mood, the ruminative habit would reoccur. This analysis therefore predicts that any interventions that improve mood state will temporarily disrupt depressive rumination, but only interventions that directly modify the context-response association will lead to long-standing reductions in depressive rumination and associated depressive vulnerability. In sum, improvements in mood can temporarily reduce rumination by removing a potential cue for the habit. However, because of their conservative nature, habits are easily reactivated and do not change unless the S-R association itself is counterconditioned. This account can partially explain the high rates of relapse and recurrence (50-80%) and the limited sustained recovery (less than 1/3 at 1 year) obtained for even our best interventions for depression (Hollon et al., 2002). We hypothesize that many interventions for depression improve symptoms in the short-term through positive expectancy, remoralization, increased activation, and therapist support, but because they do not directly target depressogenic habits like rumination, they leave patients vulnerable to relapse. A novel testable prediction is that post-treatment measures HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 20 indexing habit strength for rumination (and alternative coping strategies) will better prospectively predict sustained recovery for depression than post-treatment beliefs, expectancies, and symptoms. One such measure is the Self-Report Habit Index, which measures the frequency and automaticity of behaviour, has good reliability and validity predicting actual habitual behavior (Orbell & Verplanken, 2010; Verplanken & Orbell, 2003; Verplanken et al., 2007), and is adaptable for different behaviors. This key implication suggests that directly targeting the automatic context-response association will improve the efficacy and durability of interventions for rumination and depression. Marteau, Holland, and Fletcher (2012) noted that most interventions aimed at changing healthrelated behaviors target reflective processes rather than automatic habits, and that this may explain the relative inefficacy of these interventions. We propose that this analysis is equally pertinent to improving mental health, because automatic mental habits (e.g. rumination) are a central process within psychopathology. To be effective at modifying the context-response association and, thereby, reducing habitual rumination, the unhelpful ruminative response to the cueing context needs to be replaced with a more helpful response, with the patient in effect learning a new more adaptive habit. This echoes Hertel (2004, p.209) recommendation towards “the training of new habits through practice in control.” Changing these habits requires “counterconditioning or training to associate the triggering cue with a response that is incompatible and thereby conflicts with the unwanted habit” (Wood & Neal, 2007, p.859). Such an intervention involves repeated practice at utilizing an alternative incompatible coping strategy (e.g., concrete thinking, relaxation) in response to the identified triggering contextual cue (e.g., sad mood) to develop the new context-response association. Critically, this habit analysis predicts that systematically counter-conditioning alternative functional responses to the cueing context for rumination will improve prevention of relapse and recurrence, whether as a distinct acute treatment or following successful acute treatment of depression. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 21 This analysis suggests that traditional CBT approaches such as thought challenging will not necessarily be effective at changing habitual rumination. Successfully challenging a thought or belief would not change the underlying S-R habit. However, thought challenging could potentially be an effective intervention for rumination if repetitively trained as an alternative coping skill in response to cues for rumination. By the same logic, cognitive bias modification (CBM) approaches used to change negative biases (Hertel & Mathews, 2011) are likely to have value in reducing habitual rumination. CBM typically involves the repeated training of desired responses, incorporates programmed contingencies between stimuli, responses, and desirable outcomes (e.g., faster task performance), and is assumed to involve the same associative and instrumental learning processes as habit formation and to work on processes that are often outside conscious awareness. Thus, Hertel and Mathews (2011, p.528) argued that “in interpretation retraining, contingencies between ambiguous situations and their pre-experimental resolutions are, in effect, counter-conditioned.” There is now initial evidence supporting the assumption that CBM influences mental habits: Hertel, Holmes, and Benbow (in press) used a variant of Jacoby’s (1996) process dissociation approach to confirm that interpretation bias training changed automatic, habitual processes rather than controlled recollection. Further, there is growing evidence that rumination is associated with biases in disengaging attention from negative information (Koster, De Lissnyder, Derakshan, & De Raedt, 2010), abstract construal (Watkins, 2008) and negative interpretative bias (Mor, Hertel, Ngo, Shachar, & Redak, in press). CBM approaches therefore seem particularly pertinent to changing mental habits. The effects of CBM may perhaps be enhanced by training adaptive biases in response to contextual cues for unwanted habits, with Hertel and Mathews (2011, p.529) arguing that “training should incorporate situational cues that typically provoke the deployment of negative biases in real life”. Practice may need to be more extensive than typically employed in current psychological interventions. Lally, Van Jaarsveld, Potts and Wardle (2010) examined the development of habits HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 22 for volunteers practising an eating, drinking, or exercise behavior daily in the same context. Selfreported automaticity of the trained response increased with repetition in the consistent context but took a median of 66 repetitions to reach a training plateau, with considerable individual variation. Moreover, to ensure the required cueing context (e.g., mood state) is active prior to practising the alternative response, treatment may require active attempts to engineer the cueing context in therapy sessions, such as mood challenges or in imago exposure to cues. Such challenges provide an opportunity to test whether the habitual response to the cue has changed. This framework suggests that assessing the habitual nature of rumination and alternative coping strategies during therapy has clinical value to determine whether a new habit has successfully been trained. Practice and training would optimally continue until the new adaptive habit reaches a self-reported asymptote. To our knowledge, there has only been one explicit attempt to test repeated training of an alternative response to the contextual cues for rumination as an intervention. Building on the evidence that concrete processing is an adaptive alternative to depressive rumination (Watkins, 2008), a proof-of-principle randomized controlled trial found that training dysphoric individuals to be more concrete when faced with difficulties reduced depression, anxiety, and rumination relative to a no-treatment control (Watkins, Baeyens, & Read, 2009). Concreteness training is a form of CBM that involves repeated practice at focusing on the specific details, context, and sequence of difficult events and asking “How the event happened?” During the training, concrete thinking is explicitly used as a response to identified warning signs for rumination, and practiced repeatedly with audio-recorded exercises. In a Phase II randomized controlled trial, concreteness training was found to be superior to treatment-as-usual in reducing rumination, worry, and depression in patients with major depression recruited in primary care (Watkins et al., 2012). A control relaxation training condition, in which patients practised progressive relaxation as an alternative response to cues for rumination, also significantly reduced depression relative to treatment-as-usual and did not significantly differ from HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 23 concreteness training. These results suggest that repeated training in any functional alternative response to rumination may be an effective intervention, consistent with the current habit analysis. Relative to relaxation training, concreteness training significantly reduced trait rumination, suggesting that interposing a cognitive alternative may be more effective at reducing habitual rumination, perhaps because it facilitates adaptive repetitive thought in place of maladaptive repetitive thought as an example of transfer-appropriate processing (see Hertel & Mathews, 2011 for full discussion). Moreover, consistent with the hypothesis that concreteness training works through establishing an alternative habitual response to replace rumination, the benefits of concreteness training were significantly stronger in those patients who reported that the practised self-help response had become habitual (Watkins et al., 2012). This habit analysis has implications for the generalizability and sustainability of clinical improvement. Several theorists (Bouton, 2000; Hertel & Mathews, 2011; Wood & Neal, 2007) have noted that new patterns of associative learning (i.e., new functional S-R associations) intended to replace older patterns of associations are inherently unstable, enabling the original patterns of learning to recur under certain circumstances. These recurrences occur because the original learning that underpins the unwanted habit remains intact following counter-conditioning or extinction, with new learning overlaid on the original learning. In these circumstances, a conditioned cue (e.g., sad mood) is in the position of potentially signalling two available cue-response associations (e.g., rumination versus concrete thinking). Which association is predominant and which behavior it evokes will be determined by the current occasion-setting context. If there are differences between the setting contexts under which the original learning and subsequent counter-conditioning occur, shifts back to the original setting context can renew the original relationship and original contingencies. A key implication of considering rumination-as-habit is that despite conditioning of new responses, the old habitual response can recur under particular circumstances, potentially leading to relapse. Thus, even after successful counter-conditioning of a new habitual response to HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 24 sad mood, there may be a lapse back into rumination when the conditioned cue is encountered in a different setting context. Moreover, because the original unwanted habit typically results from a large number of learning trials in which the triggering cue and the habitual response were paired over many different settings and situations, more setting contexts will be associated with the original unwanted habit than the replacement habit, which may be constrained to fewer contexts (e.g., the therapeutic setting). One way to counter these renewal effects is to promote the retrieval of the new learning (i.e., the new habit) through explicit retrieval cues and reminders throughout and after the training (e.g., flashcards, texts from therapist, Hertel & Mathews, 2011). Another approach is to increase the generalization of the counter-conditioning by conducting the training across different and varied contexts (e.g., using multiple variants of the cueing context; pairing sad mood with new response in different settings: at home, at the office, when alone, with other people; see Hertel & Mathews, 2011 for further detail). In addition, the performance of unwanted habits becomes more likely when individuals are under cognitive load, distracted, preoccupied, or stressed (Botvinick & Blysma, 2005; Schwabe & Wolf, 2011). We hypothesize that the habitual ruminative response is more likely to be triggered under circumstances of stress, pressure, or fatigue. The ruminative response is thus likely to be hardest to stop at those times when individuals most need to stop it. The habit literature suggests a further way to control habitual rumination is by “inhibiting the performance of the habitually cued response once it has been activated” (Wood & Neal, 2007, p. 854). Quinn, Pascoe, Wood, and Neal (2010) provided evidence from episode-sampling studies that vigilant monitoring (thinking “don’t do it”; watching for slipups) was the best strategy at selfcontrol of strong habits in daily life, relative to do nothing, stimulus control, and distraction. However, inhibition of habitual behaviors requires the availability of sufficient levels of effortful self-control: on days when students had a sustained load on self-control, they were more likely to fail at overriding habitual behaviors but not non-habitual behaviors (Neal & Wood, 2007). HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 25 Moreover, self-control is a finite resource that is depleted following effortful attempts to inhibit or control thoughts, feelings, and actions (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). It is likely to be reduced in patients with depression (Joormann, 2010). This raises questions over the long-term sustainability of effortful inhibition of strong habits in daily life. Inhibition of habitual responses may most usefully contribute to long-term change by interrupting a habitual response to enable a new pattern of responding to be counter-conditioned. Focusing on self-control and inhibition in habits is particularly relevant to habitual rumination because difficulties in turning attention away from negative stimuli are characteristic of rumination. It remains unresolved to what extent these difficulties reflect difficulties in disengaging attention from negative material (Koster, De Lissnyder, Derakshan, & De Raedt, 2010) and/or difficulties in inhibiting no-longer-relevant material (Joormann, 2006, 2010). Consistent with the former, habitual rumination is correlated with selective attentional bias towards sad faces (Joormann, 2004; Joormann, Dkane, & Gotlib, 2006) and negative words (Donaldson, Lam, & Mathews, 2007), although the causal direction of this relationship is not yet determined. Consistent with the latter, habitual rumination is correlated with poor performance on inhibition-related tasks including negative affective priming (e.g., Joormann, 2006) and suppression-induced forgetting (Hertel & Gerstle, 2003), and with difficulties in removing now-irrelevant information from working memory (Joormann & Gotlib, 2008; Joormann, Levens & Gotlib, 2011). Interventions that strengthen inhibitory control or effortful self-control may thus have potential to reduce the expression of habitual rumination. There is preliminary evidence that it may be possible to improve working memory capacity through repeated training on cognitive tasks (e.g., Jaeggi, Buschkeuhl, Jonides, & Perrig, 2008), and that repeated practice can strengthen selfregulatory control (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). If robust and replicable, such cognitive training has potential to improve self-control of habitual rumination as part of a treatment intervention, particularly if combined with counter-conditioning of alternative responses. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 26 We note that this habit analysis is not necessarily unique to rumination. Because the theoretical framework is based on generic concepts of conditioning and habit formation, the principles articulated could be applied to other behaviors and emotional regulation strategies. Nevertheless, our focus in this paper was to consider the value of applying this approach to habitual rumination, and to reconcile state episodes of repetitive thought engendered by goal discrepancy with trait habitual tendency towards rumination. We further note that rumination may be harder to break than other habits such as those involving overt behavioural routines. First, rumination tends to be triggered by internal states, which makes it harder to successfully use stimulus/environmental control. Second, changing habits requires a concerted and deliberate attempt at self-control in the form of generating an alternative non-habitual response. However, habitual rumination reduces an individuals’ ability to exert such self-control because of its impact on executive control and working memory (e.g., Curci et al., 2013; Watkins & Brown, 2002). Thus, unlike many habits, by dint of occupying mental resources, rumination may be harder to change, indicating the importance of training ruminators into new habits, for example, by CBM. Conclusion We have articulated a habit-goal framework of depressive rumination that elaborates on conceptualizations of depressive rumination as a mental habit (Hertel, 2004) and recent work considering the relationship between goals and habits (Wood & Neal, 2007). This approach links RST and Control Theory by explicating the mechanisms and conditions by which state episodes of goal-discrepancy repetitive thought could develop into habitual depressive rumination. Further, this habit account generates new insights and testable predictions concerning the developmental antecedents of individual differences in rumination. The habitual nature of depressive rumination provides a partial account of why it can be so difficult to break free of rumination. Understanding the possible conditions and mechanisms that influence habit formation and habit change provides a new perspective on how to optimise psychological interventions for depressive rumination. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 27 This manuscript reflects an ongoing collaboration between the authors, with an original draft complete when Susan Nolen-Hoeksema tragically passed away. It is hoped that in some small part, this final manuscript pays tribute to Susan, her wisdom and thoroughness, her friendship, and her work, by elaborating on her seminal conceptualization of rumination and showing new insights and value. Susan was first in research, first in teaching and first in the hearts of her peers and students; as a collaborator, she made ideas flow in a way that was exciting and exhilarating: she will be greatly missed. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 28 References Bargh, J. A. (1994). The four horsemen of automaticity: Awareness, intention, efficiency, and control in social cognition. In R. S. Wyer & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition (Vol. 1, pp. 1– 40). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Beukeboom, C. J., & Semin, G. R. (2005). Mood and representations of behaviour: The how and why. Cognition and Emotion, 19, 1242-1251. Botvinick, M. M., & Bylsma, L. M. (2005). Distraction and action slips in an everyday task: Evidence for a dynamic representation of task context. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 12, 1011–1017. Bouton, M. E. (2000). A learning theory perspective on lapse, relapse, and the maintenance of behavior change. Health Psychology, 19, 57–63. Broderick, P. C., & Korteland, C. (2004). A prospective study of rumination and depression in early adolescence. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9, 383-394. Brunstein, J. C. & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1996). Effects of failure on subsequent performance: The importance of self-defining goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 395-407. Carver, C. S. & Scheier, M. F. (1982). Control-Theory - A Useful Conceptual-Framework for PersonalitySocial, Clinical, and Health Psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 92, 111-135. Cimpian, A., Arce, H-M.C., Markman, E.M., & Dweck, C.S. (2007). Subtle linguistic cues affect children’s motivation. Psychological Science, 18, 314-316. Conway, M., Mendelson, M., Giannopoulos, C., Csank, P. A. R., & Holm, S. L. (2004). Childhood and adult sexual abuse, rumination on sadness, and dysphoria. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 393-410. Cox, S.J., Mezulis, A.H., & Hyde, J.S. (2010). The influence of child gender role and maternal feedback to child stress on the emergence of the gender difference in pathological rumination in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 46, 842-852. Curci, A., Lanciano, T., Soleti, E., & Rimé, B. (2013). Negative emotional experiences arouse rumination and affect working memory capacity. Emotion. Advance online publication: doi:10.1037/a0032492 HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 29 Dickinson, A. (1985). Actions and Habits: the development of behavioural autonomy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, series B, Biological Sciences, 308, 67-78. Donaldson, C., Lam, D., & Mathews, A. (2007). Rumination and attention in major depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2664-2678. Ehring, T., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1, 192-205. Ferster, C.B. (1973). Functional analysis of depression. American Psychologist, 28, 857-870. Gaté, M.A., Watkins, E.R., Simmons, J.G., Byrne, M.L., Schwartz, O.S., Whittle, S., Sheeber, L., & Allen, N.B. (2013). Maternal parenting behaviors and adolescent depression: The mediating role of rumination. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42, 348-357. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.755927 Giorgio J.M., Sanflippo, J., Kleiman, E., Reilly, D., Bender, R.E., Wagner, C.A., Liu, R.T., & Alloy L.B. (2010). An experiential avoidance conceptualization of pathological rumination: Three tests of the model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 1021-1031. Goschke, T. & Kuhl, J. (1993). Representation of Intentions - Persisting Activation in Memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Learning Memory and Cognition, 19, 1211-1226. Gupta, P., & Cohen, N. J. (2002). Theoretical and computational analysis of skill learning, repetition priming, and procedural memory. Psychological Review, 109, 401–448. Harvey, A. G., Watkins, E., Mansell, W., & Shafran, R. (2004). Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hertel, P. T. (1998). Relation between rumination and impaired memory in dysphoric moods. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 166-172. Hertel, P.T. (2004). Memory for emotional and non-emotional events in depression: a question of habit. In D. Reisberg & P. Hertel (Eds.) Memory and Emotion (pp. 186-216). New York: Oxford University Press. Hertel, P. T., & Gerstle, M. (2003). Depressive deficits in forgetting. Psychological Science, 14, 573-578. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 30 Hertel, P.T., Holmes, M., & Benbow, A. (in press). Interpretative habit is strengthened by cognitive bias modification. Memory. Hertel, P.T., & Mathews, A. (2011). Cognitive Bias Modification: past perspectives, current findings and future applications. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 521-536. Hertel, P. T., & Rude, S. S. (1991). Depressive deficits in memory: Focusing attention improves subsequent recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 120, 301-309. Hollon, S. D., Munoz, R. F., Barlow, D. H., Beardslee, W. R., Bell, C. C., Bernal, G. et al. (2002). Psychosocial intervention development for the prevention and treatment of depression: Promoting innovation and increasing access. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 610-630. Hull. C. L. (1943). Principles of behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., & Perrig, W. J. (2008). Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 6829-6833. Jacoby, L. L. (1996). Dissociating automatic and consciously controlled effects of study/test compatibility. Journal of Memory and Language, 35, 32-52. Ji, M.F., & Wood, W. (2007). Purchase and consumption habits: not necessarily what you intend. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 261-276. Jones, N.P., Siegle, G.J., & Thase, M. E. (2007). Effects of rumination and initial severity on remission to cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 591-604. Joormann, J. (2004). Attentional bias in dysphoria: The role of inhibitory processes. Cognition & Emotion, 18, 125-147. Joormann, J. (2006). The relation of rumination and inhibition: Evidence from a negative priming task. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30, 149-160. Joormann, J. (2010). Cognitive inhibition and emotion regulation in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19 (3), 161-166. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 31 Joormann, J., Dkane, M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2006). Adaptive and maladaptive components of rumination? Diagnostic specificity and relation to depressive biases. Behavior Therapy, 37, 269-281. Joormann, J., Levens, S. M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Sticky thoughts: Depression and rumination are associated with difficulties manipulating emotional material in working memory. Psychological Science, 22 (8), 979-983. Joormann, J., & Gotlib, I. H., (2008). Updating the contents of working memory in depression: Interference from irrelevant negative material. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 182-192. Jose, P., & Brown, I. (2008). When does the association between gender and rumination begin? Gender and age differences in the use of rumination by adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 180–192. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9166-y Kamins, M.L., & Dweck, C.S. (1999). Person versus process praise and criticism: Implications for contingent self-worth and coping. Developmental Psychology, 35, 835–847. Kingston, R. E. F., and Watkins, E. R. (in prep). Believing that rumination is helpful increases rumination in response to stress. Kingston, R. E. F., Watkins, E. R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (under review). Investigating the reinforcing functions of depressive rumination. Kingston, R. E. F., Watkins, E. R., & O’Mahen, H. A. (in prep.). A prospective examination of risk factors for repetitive negative thought. Koster, E.H.W., De Lissnyder, E., Derakshan, N., & De Raedt, R. (2011). Understanding pathological rumination from a cognitive science perspective: The impaired disengagement hypothesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 138-145. Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C.H.M., Potts, H.W.W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998-1009. Mackintosh, N.J. (1983). Conditioning and associative learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Marteau, T.M., Hollands, G.J., & Fletcher, P.C. (2012). Changing human behavior to prevent disease: the importance of targeting automatic processes. Science, 337, 1492-1495. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 32 Martell, C. R., Addis, M. E., & Jacobson, N. S. (2001). Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. New York: Norton. Martin, L. L. & Tesser, A. (1989). Toward a motivational and structural theory of ruminative thought. In J.S.Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought (pp. 306-326). New York: Guilford Press. Martin, L. L. & Tesser, A. (1996). Some ruminative thoughts. In R.S.Wyer (Ed.), Ruminative thoughts. Advances in social cognition Vol 9 (pp. 1-47). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mor, N., Hertel, P.T., Ngo, T.A., Schachar, T., & Redak, S. (in press). Interpretation bias characterizes trait rumination. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R.F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does selfcontrol resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126, 247-259. Neal, D. T., & Wood, W. (2007). Automaticity in situ: Direct context cuing of habits in daily life. In J. A. Bargh, P. Gollwitzer, & E. Morsella (Eds.), Psychology of action (Vol. 2): Mechanisms of human action. London: Oxford University Press. Neal, D.T., Wood, W., Labrecque, J.S., & Lally, P. (2011). How do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual triggers of habits in daily life. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.011 Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to Depression and Their Effects on the Duration of Depressive Episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569-582. Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 504-511. Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Larson, J., & Grayson, C. (1999). Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1061-1072. Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Morrow, J. (1991). A Prospective-Study of Depression and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms After A Natural Disaster - the 1989 Loma-Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 115-121. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 33 Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Mumme, D., Wolfson, A., & Guskin, K. (1995). Helplessness in Children of Depressed and Nondepressed Mothers. Developmental Psychology, 31, 377-387. Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Watkins, E.R., (2011). A Heuristic for Transdiagnostic Models of Psychopathology: Explaining Multifinality and Divergent Trajectories. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 589-609. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419672. Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400-424. Oatley, K. & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1987). Towards a cognitive theory of emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 1, 29-50. Orbell, S. & Verplanken, B. (2010). The automatic component of habit in health behavior: Habit as cuecontingent automaticity. Health Psychology, 29, 374-383. Ouellette, J. A., & Wood, W. (1998). Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 54–74. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.54. Quinn, J.M., Pascoe, A., Wood, W., & Neal, D.T. (2010). Can’t control yourself? Monitor those bad habits. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 499-511. Rescorla, R.A., & Wagner, A.R. (1972). A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory, A.H. Black and W.F. Prokasy (eds), pp. 64-99. New York: AppletonCentury-Crofts. Roberts, J. E., Gilboa, E., & Gotlib, I. H. (1998). Ruminative response style and vulnerability to episodes of dysphoria: Gender, neuroticism, and episode duration. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 401423. Schmaling, J., Dimidjian, S., Katon, W., & Sullivan, M. (2006). Response styles among patients with minor depression and dysthymia in primary care. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 350-356. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 34 Schwabe, L., & Wolf, O.T. (2011). Stress-induced modulation of instrumental behaviour: From goaldirected to habitual control of action. Behavioural Brain Research, 219, 321-328. Spasojevic, J. & Alloy, L. B. (2002). Who becomes a depressive ruminator? Developmental antecedents of ruminative response style. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 16, 405-419. Verplanken, B. (2006). Beyond frequency: Habit as mental construct. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 639–656. Verplanken, B., Friborg, O., Wang, C. E., Trafimow, D., & Woolf, K. (2007). Mental habits: Metacognitive reflection on negative self-thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 526-541. Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2003). Reflections on past behavior: A self-report index of habit strength. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 1313–1330. Verplanken, B., & Wood, W. (2006). Interventions to break and create consumer habits. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25, 90–103. Watkins, E. & Baracaia, S. (2001). Why do people ruminate in dysphoric moods? Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 723-734. Watkins, E. & Brown, R. G. (2002). Rumination and executive function in depression: an experimental study. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 72, 400-402. Watkins, E., Scott, J., Wingrove, J., Rimes, K., Bathurst, N., Steiner, H. et al. (2007). Rumination-focused cognitive-behaviour therapy for residual depression: a case series. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2144-2154. Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 163-206. Watkins, E.R. (2011). Dysregulation in Level of Goal and Action Identification Across Psychological Disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 260-278. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 35 Watkins, E. R., Baeyens, C. B., & Read, R. (2009). Concreteness training reduces dysphoria: Proof-ofprinciple for repeated cognitive bias modification in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 55-64. Watkins, E. R., Moberly, N. J., & Moulds, M. (2008). Processing mode causally influences emotional reactivity: Distinct effects of abstract versus concrete construal on emotional response. Emotion, 8, 364-378. Watkins, E.R., Moberly, N.J., & Moulds, M.L. (2011). When the ends outweigh the means: Mood and level-of-identification in depression. Cognition and Emotion. 25, 1214-1227. Watkins, E. R., & Moulds, M. (2005). Distinct modes of ruminative self-focus: Impact of abstract versus concrete rumination on problem solving in depression. Emotion, 5, 319-328. Watkins, E.R., Mullan, E.G., Wingrove, J., Rimes, K., Steiner, H., Bathurst, N., Eastman, E., & Scott, J. (2011). Rumination-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for residual depression: phase II randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 317- 322. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.090282. Watkins, E.R., Taylor, R.S., Byng, R., Baeyens, C.B., Read, R., Pearson, K., & Watson, L. (2012). Guided self-help concreteness training as an intervention for major depression in primary care: a Phase II randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 42, 1359-1373. doi:10.1017/S0033291711002480. Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behaviour change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 249–268. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249. Wood, W., & Neal, D.T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychological Review, 114, 843-863. Wood, W., Tam, L., & Witt, M. G. (2005). Changing circumstances, disrupting habits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 918–933. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.918. HABIT FRAMEWORK OF DEPRESSIVE RUMINATION 36 Zeigarnik, B. (1938). On finished and unfinished tasks. In W.D.Ellis (Ed.), A source book of gestalt psychology (pp. 300-314). New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, & World.