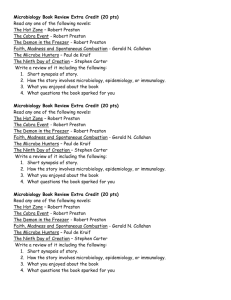

The economy of shorter hours: letter from Gardner`s of Preston, to

advertisement

The economy of shorter hours: letter from Gardner's of Preston, to the chairman of meeting in Corn Exchange, Manchester, 22 April 1845 (Parliamentary.Papers, 1845, XXV, pp. 456-457; in G. M. Young and W. D. Hancock, eds., English Historical Documents, XII(1), 1833-1874 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956), pp. 980-81. As factory legislation gradually created a set of regulations enforced by inspectors, more radical voices called for the shortening of the working days to ten hours. While most factory owners bitterly opposed such government regulation, some, such as this mill owner from Preston, argued that shorter hours increased productivity.) SIR, -It was my intention to have been with you this evening, but a severe cold makes it quite unsafe for me to venture out. As I believe some opinion or expression of feeling will be expected from me, as to the conclusions I may have come to from the working of my Preston mill, for the past 12 months, 11 instead of 12 hours each day, as previously, I therefore avail myself of the present opportunity of stating that I am quite satisfied that both as much yarn and power-loom cloth may be produced at quite as low a cost in 11 as in 12 hours per day; at least, that it has been so the last 12, months, in my mills at Preston. So fully satisfied am I on this point, that if it should please God to spare my life to the season of the present year when we light up again, it is my present intention to make a further reduction of time to 10 1/2 hours, without the slightest fear of suffering loss by it. I find the hands work with greater energy and spirit; they are more cheerful, and apparently more happy. All the arguments I have heard in favour of long time appear based on an arithmetical question, -if 11 produce so much, what will 12, 13, or even 15 hours produce? This is correct, as far as the steam-engine is concerned; whatever it will produce in 11 hours, it will produce double the quantity in 22. But try this on the animal horse, and you will soon find he cannot compete with the engine, as he requires both time to rest and feed. My much respected manager and friend, Mr. Heaton, tells me he has passed all the grades of a mill, and has worked 11, 12, 13, and even 14 hours per day, and was daily exhausted; but he says they knew their hours, and worked accordingly-that he would have done more and better work in less time. It is, I believe, a fact not questioned, that there is more bad work made the last one or two hours of the day than the whole of the first nine or ten hours. There can be no doubt but 11 hours are quite sufficient for any one to exhaust the whole of his or her strength in any one occupation, situation, or atmosphere, although the work is not laborious. It can be no small gratification to any employer of a large number of hands to see them healthy and happy, with an opportunity of improving their minds. I am satisfied those mills that work short hours will have a choice of hands, and then individual interest will accomplish what is necessary, without the intervention of the Legislature. I beg to state that, about 20 years ago, we had many orders for a style of goods much wanted. At the time we had about 30 Young women, none under 20 or over 40 years of age, winding coloured yarn in our Manchester warehouse; the principal part was at Bolton and Preston. To increase the quantity of the work, I requested they would work (instead of 11) 12, hours. At the end of the week, I found they had got a mere trifle more work done; but, supposing there was some incidental cause for this, I requested they would work 13 hours the following week, at the end of which they had produced less instead of more work. The overlooker told me the hours were too long, and invited me to be in the room with them the last hour of the day. I saw they were exhausted, drowsy, and making bad work and little of it; I therefore reduced their time two hours, as before. Since that time I have been an advocate for shorter hours of labour. - ROBERT GARDNER - April 22nd, 1845