Assessing the Impact of Structural Adjustment Programs on Women

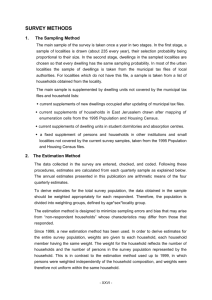

advertisement