WORD - The University of Sydney

advertisement

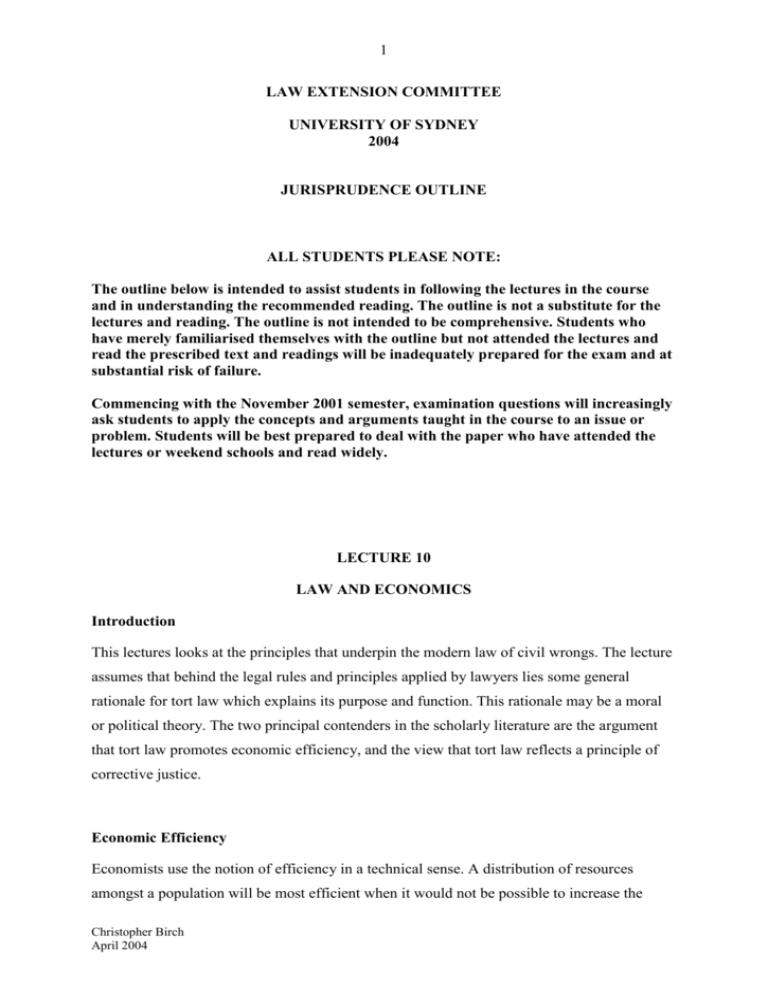

1 LAW EXTENSION COMMITTEE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY 2004 JURISPRUDENCE OUTLINE ALL STUDENTS PLEASE NOTE: The outline below is intended to assist students in following the lectures in the course and in understanding the recommended reading. The outline is not a substitute for the lectures and reading. The outline is not intended to be comprehensive. Students who have merely familiarised themselves with the outline but not attended the lectures and read the prescribed text and readings will be inadequately prepared for the exam and at substantial risk of failure. Commencing with the November 2001 semester, examination questions will increasingly ask students to apply the concepts and arguments taught in the course to an issue or problem. Students will be best prepared to deal with the paper who have attended the lectures or weekend schools and read widely. LECTURE 10 LAW AND ECONOMICS Introduction This lectures looks at the principles that underpin the modern law of civil wrongs. The lecture assumes that behind the legal rules and principles applied by lawyers lies some general rationale for tort law which explains its purpose and function. This rationale may be a moral or political theory. The two principal contenders in the scholarly literature are the argument that tort law promotes economic efficiency, and the view that tort law reflects a principle of corrective justice. Economic Efficiency Economists use the notion of efficiency in a technical sense. A distribution of resources amongst a population will be most efficient when it would not be possible to increase the Christopher Birch April 2004 2 satisfied preferences of any member of the population without decreasing the level of satisfied preference of others (a so-call Pareto equilibrium, named after the economist Vilfedo Pareto). This notion of efficiency depends upon the following assumptions:1. That members of the population are rational maximisers of their own self interest; 2. That there exists free exchange in accordance with the principles of a perfect market amongst each member of the population; and 3. There has been an allocation of goods to individuals to hold privately in which they may trade. The concept of a perfect market depends upon the following assumptions: 1. A private stable allocation of resources; 2. The absence of force or fraud in regard to all transactions within the market; 3. That no one person can influence prices; 4. That each person acts in accordance with their own rational self interest; 5. That transactions are costless; It is sometimes also specified that each participant should have full appropriate knowledge regarding any transactions they enter into. If they lack such knowledge transactions will not be costless as they will need to expend effort in obtaining knowledge necessary to know whether the transaction will be more beneficial than not. The Market Principle and Political Economy The notion of rational maximisation of the satisfaction of preferences is at least conceptually related to the utilitarian doctrine of the maximisation of the happiness of the greatest number. The advantage of market theory is that it avoids the problem of judging inter-subjective preferences. Rather than someone making a decision about what is to be considered in the best interests of all, a market allows each person to determine what exchanges they wish to make. Fredrick Hayek, the Austrian economist, considered that markets were an efficient means of distributing resources because they were better at exchanging information about individual preferences than central government planners (See his principles of Taxis and Cosmos) Christopher Birch April 2004 3 It must however be recognised that while a market may be efficient in the Pareto sense it need not be just. The Pareto equilibrium will be different in every case for each different original allocation of resources. If the original allocation of resources was unjust, the Pareto equilibrium may also be unjust. Further, Coase demonstrated by way of a careful thought experiment that in a perfect market given any initial distribution, and the marginal profitability of activities, people will agree to produce in accordance with the highest marginal profitability whatever be the legal liabilities imposed upon those various activities (Coase’s theorem). Market Failure Some economists argued that even a perfect market ignored certain costs because they were not costs to the parties to the transactions. They referred to these costs as externalities. (A typical example is the pollution cost of buying a motor vehicle borne by the community at large rather than the parties to the transaction). It was argued that legal intervention was required to impose external costs upon the parties to ensure that society did not otherwise over invest in such activities. Coase’s theorem casts doubt upon some of these arguments regarding externalities. Coase’s theorem shifted the emphasis from the notion of externality to the problem of transaction cost. Efficient outcomes will only be arrived at in a perfect market, which is one in which transactions are costless, and the parties have complete knowledge. Legal intervention will therefore be necessary to seek to produce the efficient outcome a market could have produced if transactions were possible but where they have been prevented by transaction costs. The Prisoners Dilemma Another famous example of market failure is generated wherever the participants in a market have a conflict between the maximisation of their individual preferences and the collective Christopher Birch April 2004 4 good. PRISONERS DILEMMA You Confess Remain Silent Each gets 10 years 1 go free You get 12 years 1 get 2 years You go free Each gets 2 years Confess I Remain Silent For further discussion of the prisoner’s dilemma, see: Parfitt; D Reasons and Persons, Oxford Up, Oxford, 1984, Chapter 2 Nozick; R Rationality, Princeton UP, Princeton, 1993, p.50-59. Moser; PK Rationality in Action, Cambridge UP, Cambridge, 1990, p.280-282 Tort Law as Reflecting a Utilitarian or Economic Principle In United States v Carol Towing 150 Fdd 169 at 173 Learned Hand J based his judgment on the following formula:If P = Probability of injury L = Injury – cost of injury B = Burden of injury (being the cost of precautions) Then where B > than P x L no liability will be imposed. Where B < rather than P x L liability will be imposed. On cost benefit analysis of safety precautions see also Flemings “Law of Tort”, 9th Edition, p.131-132. Posner’s Theory Richard Posner has sought to analyse all bodies of law from the point of view of economic Christopher Birch April 2004 5 efficiency, arguing that this is the underlying principle of all legal doctrine. In explaining tort law, Posner argues that compensatory damages are paid to a victim to give the victim an incentive to sue. This is essential to the maintenance of the tort system as an effective credible deterrent to negligence. The economic function of compensation in tort, according to Posner, is the deterrence of inefficient accidents. Posner argues that the legal principles aim to achieve an outcome comparable to that which would represent the most economically efficient outcome if the matter was capable of being handled by a market. The reason the law intervenes is because the conduct with which law is concerned is usually one in which a market is inappropriate because of the cost of the transactions or some other cause of market failure. Criticisms of Posner’s Theory One peculiarity of Posner’s theory is that it argues that law generally, and tort law in particular, seeks through its principles of negligence and the like, to emulate market efficiency, and yet, few judgments refer to economic efficiency as a reason or explanation of the legal principles applied. Posner suggests that legal principles that promote economic efficiency will be more likely to be promoted and applied than ones that do not, rather like survival of the fittest. A further difficulty with Posner’s theory is that it is hard to know whether the outcomes produced by law truly reflect how a society would organise itself if market principles could be applied. Corrective Justice In the last 20 years a number of jurists have suggested that the principles underpinning tort law are not the promotion of economic efficiency but rather those of corrective justice. The concept can be traced to Aristotle’s Nicomachean ethics. As explained by Aristotle, the concept of corrective justice involved depriving a wrongdoer of the gain and providing compensation to the sufferer. Christopher Birch April 2004 6 The aim is to ensure that each party is returned to the position that he or she was in before the wrong was committed. The notion of corrective justice is related to and dependent upon the concept of distributive justice. Distributive justice concerns those principles that govern the overall distribution of goods (using that term in the widest possible sense). If we assume that the pre-accident distribution was just, then the effect of a wrong is to disturb that just distribution. Corrective justice demands that the original just distribution be restored. Justice and Proportionality There are many obstacles to explaining modern tort law as an application of corrective justice. It troubles many commentators that a wrongdoer could be liable for damages out of all proportion to the level of wrongdoing committed. Judith Thompson has argued that we should have an “at- fault” pool to compensate victims. Everyone contributes to the pool a sum for any wrongdoing proportionate to their level of wrongdoing, and those injured are compensated from the pool in an amount necessary to put them back in their pre-accident position to the extent money can. This seeks to neutralise the effect of luck. Joel Feinberg has argued that we can explain the tort principle on the “fault forfeits first” principle. Once someone has been injured the loss must be borne. It is better that it be borne by the party at fault then by the innocent party. Jeremy Waldron has argued that the modern law of tort cannot satisfy principles of corrective justice as the liabilities of the defendant cannot be shown to correlate with culpability or moral dessert. Ironically, despite the difficulty of jurists in coming up with a consistent theory of corrective justice that explains modern tort law, judgments in tort are usually expressed in the language of blame and wrongdoing rather then economic efficiency. Further, modern tort law is to a substantial degree underpinned by insurance and the consequent spreading of risks, although this is rarely adverted to in judgments. Should this Christopher Birch April 2004 7 matter to judicial decision makers? Conclusion It may well be that modern tort law is built upon a mix of inconsistent principles and justifications. The difficulty presently experienced by superior appellate courts in defining the circumstances in which recovery of pure economic loss will be permitted may be a reflection of this deeper conceptual confusion. See Perre v Apand (1999) 198 CLR 180. Christopher Birch April 2004