Running Out of Planet to Exploit

advertisement

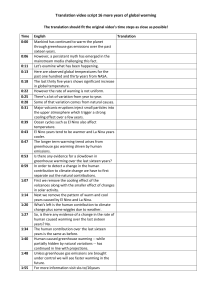

Running Out of Planet to Exploit By PAUL KRUGMAN Published: April 21, 2008 Nine years ago The Economist ran a big story on oil, which was then selling for $10 a barrel. The magazine warned that this might not last. Instead, it suggested, oil might well drop to $5 a barrel. In any case, The Economist asserted, the world faced “the prospect of cheap, plentiful oil for the foreseeable future.” Last week, oil hit $117. It’s not just oil that has defied the complacency of a few years back. Food prices have also soared, as have the prices of basic metals. And the global surge in commodity prices is reviving a question we haven’t heard much since the 1970s: Will limited supplies of natural resources pose an obstacle to future world economic growth? How you answer this question depends largely on what you believe is driving the rise in resource prices. Broadly speaking, there are three competing views. The first is that it’s mainly speculation — that investors, looking for high returns at a time of low interest rates, have piled into commodity futures, driving up prices. On this view, someday soon the bubble will burst and high resource prices will go the way of Pets.com. The second view is that soaring resource prices do, in fact, have a basis in fundamentals — especially rapidly growing demand from newly meat-eating, car-driving Chinese — but that given time we’ll drill more wells, plant more acres, and increased supply will push prices right back down again. The third view is that the era of cheap resources is over for good — that we’re running out of oil, running out of land to expand food production and generally running out of planet to exploit. I find myself somewhere between the second and third views. There are some very smart people — not least, George Soros — who believe that we’re in a commodities bubble (although Mr. Soros says that the bubble is still in its “growth phase”). My problem with this view, however, is this: Where are the inventories? Normally, speculation drives up commodity prices by promoting hoarding. Yet there’s no sign of resource hoarding in the data: inventories of food and metals are at or near historic lows, while oil inventories are only normal. The best argument for the second view, that the resource crunch is real but temporary, is the strong resemblance between what we’re seeing now and the resource crisis of the 1970s. What Americans mostly remember about the 1970s are soaring oil prices and lines at gas stations. But there was also a severe global food crisis, which caused a lot of pain at the supermarket checkout line — I remember 1974 as the year of Hamburger Helper — and, much more important, helped cause devastating famines in poorer countries. In retrospect, the commodity boom of 1972-75 was probably the result of rapid world economic growth that outpaced supplies, combined with the effects of bad weather and Middle Eastern conflict. Eventually, the bad luck came to an end, new land was placed under cultivation, new sources of oil were found in the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea, and resources got cheap again. But this time may be different: concerns about what happens when an ever-growing world economy pushes up against the limits of a finite planet ring truer now than they did in the 1970s. For one thing, I don’t expect growth in China to slow sharply anytime soon. That’s a big contrast with what happened in the 1970s, when growth in Japan and Europe, the emerging economies of the time, downshifted — and thereby took a lot of pressure off the world’s resources. Meanwhile, resources are getting harder to find. Big oil discoveries, in particular, have become few and far between, and in the last few years oil production from new sources has been barely enough to offset declining production from established sources. And the bad weather hitting agricultural production this time is starting to look more fundamental and permanent than El Niño and La Niña, which disrupted crops 35 years ago. Australia, in particular, is now in the 10th year of a drought that looks more and more like a long-term manifestation of climate change. Suppose that we really are running up against global limits. What does it mean? Even if it turns out that we’re really at or near peak world oil production, that doesn’t mean that one day we’ll say, “Oh my God! We just ran out of oil!” and watch civilization collapse into “Mad Max” anarchy. But rich countries will face steady pressure on their economies from rising resource prices, making it harder to raise their standard of living. And some poor countries will find themselves living dangerously close to the edge — or over it. Don’t look now, but the good times may have just stopped rolling Op-Ed Columnist An Affordable Truth By PAUL KRUGMAN Published: December 6, 2009 Maybe I’m naïve, but I’m feeling optimistic about the climate talks starting in Copenhagen on Monday. President Obama now plans to address the conference on its last day, which suggests that the White House expects real progress. It’s also encouraging to see developing countries — including China, the world’s largest emitter of carbon Of course, if things go well in Copenhagen, the usual suspects will go wild. We’ll hear cries that the whole notion of global warming is a hoax perpetrated by a vast scientific conspiracy, as demonstrated by stolen e-mail messages that show — well, actually all they show is that scientists are human, but never mind. We’ll also, however, hear cries that climate-change policies will destroy jobs and growth. The truth, however, is that cutting greenhouse gas emissions is affordable as well as essential. Serious studies say that we can achieve sharp reductions in emissions with only a small impact on the economy’s growth. And the depressed economy is no reason to wait — on the contrary, an agreement in Copenhagen would probably help the economy recover. Why should you believe that cutting emissions is affordable? First, because financial incentives work. Action on climate, if it happens, will take the form of “cap and trade”: businesses won’t be told what to produce or how, but they will have to buy permits to cover their emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. So they’ll be able to increase their profits if they can burn less carbon — and there’s every reason to believe that they’ll be clever and creative about finding ways to do just that. As a recent study by McKinsey & Company showed, there are many ways to reduce emissions at relatively low cost: improved insulation; more efficient appliances; more fuel-efficient cars and trucks; greater use of solar, wind and nuclear power; and much, much more. And you can be sure that given the right incentives, people would find many tricks the study missed. The truth is that conservatives who predict economic doom if we try to fight climate change are betraying their own principles. They claim to believe that capitalism is infinitely adaptable, that the magic of the marketplace can deal with any problem. But for some reason they insist that cap and trade — a system specifically designed to bring the power of market incentives to bear on environmental problems — can’t work. Well, they’re wrong — again. For we’ve been here before. The acid rain controversy of the 1980s was in many respects a dress rehearsal for today’s fight over climate change. Then as now, right-wing ideologues denied the science. Then as now, industry groups claimed that any attempt to limit emissions would inflict grievous economic harm. But in 1990 the United States went ahead anyway with a cap-and-trade system for sulfur dioxide. And guess what. It worked, delivering a sharp reduction in pollution at lowerthan-predicted cost. Curbing greenhouse gases will be a much bigger and more complex task — but we’re likely to be surprised at how easy it is once we get started. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that by 2050 the emissions limits in recent proposed legislation would reduce real G.D.P. by between 1 percent and 3.5 percent from what it would otherwise have been. If we split the difference, that says that emissions limits would slow the economy’s annual growth over the next 40 years by around one-twentieth of a percentage point — from 2.37 percent to 2.32 percent. That’s not much. Yet if the acid rain experience is any guide, the true cost is likely to be even lower. Still, should we be starting a project like this when the economy is depressed? Yes, we should — in fact, this is an especially good time to act, because the prospect of climatechange legislation could spur more investment spending. Consider, for example, the case of investment in office buildings. Right now, with vacancy rates soaring and rents plunging, there’s not much reason to start new buildings. But suppose that a corporation that already owns buildings learns that over the next few years there will be growing incentives to make those buildings more energy-efficient. Then it might well decide to start the retrofitting now, when construction workers are easy to find and material prices are low. The same logic would apply to many parts of the economy, so that climate change legislation would probably mean more investment over all. And more investment spending is exactly what the economy needs. So let’s hope my optimism about Copenhagen is justified. A deal there would save the planet at a price we can easily afford — and it would actually help us in our current economic predicament. December 7, 2009 In Face of Skeptics, Experts Affirm Climate Peril By ANDREW C. REVKIN and JOHN M. BRODER Published: December 6, 2009 Just two years ago, a United Nations panel that synthesizes the work of hundreds of climatologists around the world called the evidence for global warming “unequivocal.” Evidence of a Warming Planet Climate Change Conversations Graphic Who’s at the Climate Talks, and What Do They Seek? Interactive Graphic Copenhagen: Emissions, Treaties and Impacts Interactive Feature Science and Politics of Climate Change Related Copenhagen Talks Tough on Climate Protest Plans (December 7, 2009) Special Report: Business of Green: U.K. Weighs a Fast Track to a Low Carbon Future (December 7, 2009) Seeking to Set an Example on the Climate Express (December 7, 2009) Times Topics: Copenhagen Climate Talks (UNFCCC) Dot Earth Blog: More on the Climate Files Enlarge This Image Johan Spanner for The New York Times Negotiations by high-ranking government officials prepared the way for the United Nations conference in Copenhagen. But as representatives of about 200 nations converge in Copenhagen on Monday to begin talks on a new international climate accord, they do so against a background of renewed attacks on the basic science of climate change. The debate, set off by the circulation of several thousand files and e-mail messages stolen from one of the world’s foremost climate research institutes, has led some who oppose limits on greenhouse gas emissions, and at least one influential country, Saudi Arabia, to question the scientific basis for the Copenhagen talks. The uproar has threatened to complicate a multiyear diplomatic effort already ensnared in difficult political, technical and financial disputes that have caused leaders to abandon hopes of hammering out a binding international climate treaty this year. In recent days, an array of scientists and policy makers have said that nothing so far disclosed — the correspondence and documents include references by prominent climate scientists to deleting potentially embarrassing e-mail messages, keeping papers by competing scientists from publication and making adjustments in research data — undercuts decades of peer-reviewed science. Yet the intensity of the response highlights that skepticism about global warming persists, even as many scientists thought the battle over the reality of human-driven climate change was finally behind them. On dozens of Web sites and blogs, skeptics and foes of greenhouse gas restrictions take daily aim at the scientific arguments for human-driven climate change. The stolen material was quickly seized upon for the questions it raised about the accessibility of raw data to outsiders and whether some data had been manipulated. An investigation into the stolen files is being conducted by the University of East Anglia, in England, where the computer breach occurred. Rajendra K. Pachauri, chairman of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, has also said he will look into the matter. At the same time, polls in the United States and Britain suggest that the number of people who doubt that global warming is dangerous or caused by humans has grown in recent years. Politics, ideology and economic interests interlace the debate, and the stakes on both sides are high. If scientific predictions about global warming’s effects are correct, inaction will lead at best to rising social, economic and environmental disruption, at worst to a calamity far more severe. If the forecasts are wrong, nations could divert hundreds of billions of dollars to curb greenhouse gas emissions at a time when they are struggling to recover from a global recession. Yet the case for human-driven warming, many scientists say, is far clearer now than a decade ago, when the skeptics included many people who now are convinced that climate change is a real and serious threat. Even some who remain skeptical about the extent or pace of global warming say that the premise underlying the Copenhagen talks is solid: that warming is to some extent driven by greenhouse gases spewing into the atmosphere from human activities like the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation. Roger A. Pielke Sr., for example, a climate scientist at the University of Colorado who has been highly critical of the United Nations climate panel and who once branded many of the scientists now embroiled in the e-mail controversy part of a climate “oligarchy,” said that so many independent measures existed to show unusual warming taking place that there was no real dispute about it. Moreover, he said, “The role of added carbon dioxide as a major contributor in climate change has been firmly established.” The Copenhagen conference itself reflects increasing acceptance of the scientific arguments: the negotiations leading to the talks were conducted by high-ranking officials of the world’s governments rather than the scientists and environment ministers who largely shaped the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Late last week, President Obama changed the date of his visit to Copenhagen to Dec. 18, the last day of the talks. For many, a 2007 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was a marker of a shift in the global warming debate. In it, the panel -- a volunteer network of hundreds of scientists from many disciplines who meet periodically to review climate studies and translate the results into language useful to policy makers -- concluded that no doubt remained that the earth was warming. Recent warming was "very likely" driven by human actions, the report said, and if unabated, posed rising risks to people and ecosystems. Over the last several decades, other reviews, by the National Academy of Sciences and other institutions, have largely echoed the panel’s findings and said the remaining uncertainties should not be an excuse for inaction. The panel’s report was built on two decades of intensive scientific study of climate patterns. Greenhouse gases warm the planet by letting in sunlight and blocking the escape of some of the resulting heat. “The physics of the greenhouse effect is so basic that instead of asking whether it would happen, it makes more sense to ask what on earth could make it not happen,” said Spencer Weart, a physicist and historian. “So far, nobody has been able to come up with anything plausible in that line.” The atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases released by humans has risen rapidly in the last century, along with industrialization and electricity use. Carbon dioxide from burning of coal, oil and natural gas is the most potent of the greenhouse gases because it can persist in the atmosphere for a century or more. Methane — from landfills, livestock and leaking pipes, tanks and wells — has recently been found to be a close second. And these gases not only have a heating effect, but also cause evaporation of water from sea and soil, producing water vapor, another powerful heat-trapping gas. In reaching its conclusion, the climate panel relied only partly on temperature data like that collected by the scientists at the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia, whose circulated e-mail correspondence set off the current uproar. It also considered a wide range of data from other sources, including measurements showing the retreat of glaciers in mountain ranges around the world, changes in the length and character of the seasons, heating of the oceans and marked retreats of sea ice in the Arctic. Since 1979, satellites have provided another check on surface temperature measurements. Strong disagreements about how to interpret the satellite data were largely resolved after the Bush administration began a review in which competing research groups worked out some of their differences. Science is about probability, not certainty. And the persisting uncertainties in climate science leave room for argument. What is a realistic estimate of how much temperatures will rise? How severe will the effects be? Are there tipping points beyond which the changes are uncontrollable? Even climate scientists disagree on many of these questions. But skeptics have been critical of the data assembled to show that warming is occurring and the analytic methods that climate scientists use, including mathematical models used to demonstrate a human cause for warming and project future trends. Both sides also have at times been criticized for overstatement in characterizing the scientific evidence. The contents of the stolen e-mail messages and documents have given fresh ammunition to the skeptics’ camp. The Climatic Research Unit’s role as a central aggregator of temperature and other climate data has also made it a target. One widely discussed file extracted from the unit’s computers, presumed to be the log of a researcher named Ian Harris, recorded his years of frustration in trying to make sense of disparate data and described procedures — or “fudge factors,” as he called them — used by scientists to eliminate known sources of error. The research in question concerned attempts to chart past temperature changes by studying direct measurements of temperature. An influential study that drew in part on the British data was challenged in 2003. In 2006, a review by the National Academy of Sciences concluded, with some reservations, that “an array of evidence” supported the broad thrust of the research. To skeptics, the purloined files suggest a conspiracy to foist an expensive policy agenda on the nations of the world and to keep inconsistent data from the public. “If we were arguing about archaeology then people could hoard their data,” said Stephen McIntyre, a blogger and retired Canadian mining consultant who since 2003 has investigated climate data, sometimes finding errors. “But I don’t think the public has any time for that” in the climate debate. Many scientists, however, deny that any important data was held back and say that the email messages and documents will in the end prove merely another manufactured controversy. “There will remain after the dust settles in this controversy a very strong scientific consensus on key characteristics of the problem,” John Holdren, President Obama’s science adviser, told a Congressional hearing last week. “Global climate is changing in highly unusual ways compared to long experienced and expected natural variations.” Whichever view prevails, the questions will undoubtedly linger well after the negotiators who are trying to work out the complex issues that still stand in the way of an international climate treaty leave Copenhagen. Andrew C. Revkin reported from New York, and John M. Broder from Washington. Op-Ed Columnist Cassandras of Climate By PAUL KRUGMAN Published: September 27, 2009 Every once in a while I feel despair over the fate of the planet. If you’ve been following climate science, you know what I mean: the sense that we’re hurtling toward catastrophe but nobody wants to hear about it or do anything to avert it. And here’s the thing: I’m not engaging in hyperbole. These days, dire warnings aren’t the delusional raving of cranks. They’re what come out of the most widely respected climate models, devised by the leading researchers. The prognosis for the planet has gotten much, much worse in just the last few years. What’s driving this new pessimism? Partly it’s the fact that some predicted changes, like a decline in Arctic Sea ice, are happening much faster than expected. Partly it’s growing evidence that feedback loops amplifying the effects of man-made greenhouse gas emissions are stronger than previously realized. For example, it has long been understood that global warming will cause the tundra to thaw, releasing carbon dioxide, which will cause even more warming, but new research shows far more carbon locked in the permafrost than previously thought, which means a much bigger feedback effect. The result of all this is that climate scientists have, en masse, become Cassandras — gifted with the ability to prophesy future disasters, but cursed with the inability to get anyone to believe them. And we’re not just talking about disasters in the distant future, either. The really big rise in global temperature probably won’t take place until the second half of this century, but there will be plenty of damage long before then. For example, one 2007 paper in the journal Science is titled “Model Projections of an Imminent Transition to a More Arid Climate in Southwestern North America” — yes, “imminent” — and reports “a broad consensus among climate models” that a permanent drought, bringing Dust Bowl-type conditions, “will become the new climatology of the American Southwest within a time frame of years to decades.” So if you live in, say, Los Angeles, and liked those pictures of red skies and choking dust in Sydney, Australia, last week, no need to travel. They’ll be coming your way in the nottoo-distant future. Now, at this point I have to make the obligatory disclaimer that no individual weather event can be attributed to global warming. The point, however, is that climate change will make events like that Australian dust storm much more common. In a rational world, then, the looming climate disaster would be our dominant political and policy concern. But it manifestly isn’t. Why not? Part of the answer is that it’s hard to keep peoples’ attention focused. Weather fluctuates — New Yorkers may recall the heat wave that pushed the thermometer above 90 in April — and even at a global level, this is enough to cause substantial year-to-year wobbles in average temperature. As a result, any year with record heat is normally followed by a number of cooler years: According to Britain’s Met Office, 1998 was the hottest year so far, although NASA — which arguably has better data — says it was 2005. And it’s all too easy to reach the false conclusion that the danger is past. But the larger reason we’re ignoring climate change is that Al Gore was right: This truth is just too inconvenient. Responding to climate change with the vigor that the threat deserves would not, contrary to legend, be devastating for the economy as a whole. But it would shuffle the economic deck, hurting some powerful vested interests even as it created new economic opportunities. And the industries of the past have armies of lobbyists in place right now; the industries of the future don’t. Nor is it just a matter of vested interests. It’s also a matter of vested ideas. For three decades the dominant political ideology in America has extolled private enterprise and denigrated government, but climate change is a problem that can only be addressed through government action. And rather than concede the limits of their philosophy, many on the right have chosen to deny that the problem exists. So here we are, with the greatest challenge facing mankind on the back burner, at best, as a policy issue. I’m not, by the way, saying that the Obama administration was wrong to push health care first. It was necessary to show voters a tangible achievement before next November. But climate change legislation had better be next. And as I pointed out in my last column, we can afford to do this. Even as climate modelers have been reaching consensus on the view that the threat is worse than we realized, economic modelers have been reaching consensus on the view that the costs of emission control are lower than many feared. So the time for action is now. O.K., strictly speaking it’s long past. But better late than never. Sign in to Recommend More Articles in Opinion » A version of this article appeared in print on September 28, 2009, on page A23 of the New York edition. Op-Ed Columnist It’s Easy Being Green By PAUL KRUGMAN Published: September 24, 2009 So, have you enjoyed the debate over health care reform? Have you been impressed by the civility of the discussion and the intellectual honesty of reform opponents? If so, you’ll love the next big debate: the fight over climate change. The House has already passed a fairly strong cap-and-trade climate bill, the WaxmanMarkey act, which if it becomes law would eventually lead to sharp reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. But on climate change, as on health care, the sticking point will be the Senate. And the usual suspects are doing their best to prevent action. Some of them still claim that there’s no such thing as global warming, or at least that the evidence isn’t yet conclusive. But that argument is wearing thin — as thin as the Arctic pack ice, which has now diminished to the point that shipping companies are opening up new routes through the formerly impassable seas north of Siberia. Even corporations are losing patience with the deniers: earlier this week Pacific Gas and Electric canceled its membership in the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in protest over the chamber’s “disingenuous attempts to diminish or distort the reality” of climate change. So the main argument against climate action probably won’t be the claim that global warming is a myth. It will, instead, be the argument that doing anything to limit global warming would destroy the economy. As the blog Climate Progress puts it, opponents of climate change legislation “keep raising their estimated cost of the clean energy and global warming pollution reduction programs like some out of control auctioneer.” It’s important, then, to understand that claims of immense economic damage from climate legislation are as bogus, in their own way, as climate-change denial. Saving the planet won’t come free (although the early stages of conservation actually might). But it won’t cost all that much either. How do we know this? First, the evidence suggests that we’re wasting a lot of energy right now. That is, we’re burning large amounts of coal, oil and gas in ways that don’t actually enhance our standard of living — a phenomenon known in the research literature as the “energy-efficiency gap.” The existence of this gap suggests that policies promoting energy conservation could, up to a point, actually make consumers richer. Second, the best available economic analyses suggest that even deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions would impose only modest costs on the average family. Earlier this month, the Congressional Budget Office released an analysis of the effects of Waxman-Markey, concluding that in 2020 the bill would cost the average family only $160 a year, or 0.2 percent of income. That’s roughly the cost of a postage stamp a day. By 2050, when the emissions limit would be much tighter, the burden would rise to 1.2 percent of income. But the budget office also predicts that real G.D.P. will be about twoand-a-half times larger in 2050 than it is today, so that G.D.P. per person will rise by about 80 percent. The cost of climate protection would barely make a dent in that growth. And all of this, of course, ignores the benefits of limiting global warming. So where do the apocalyptic warnings about the cost of climate-change policy come from? Are the opponents of cap-and-trade relying on different studies that reach fundamentally different conclusions? No, not really. It’s true that last spring the Heritage Foundation put out a report claiming that Waxman-Markey would lead to huge job losses, but the study seems to have been so obviously absurd that I’ve hardly seen anyone cite it. Instead, the campaign against saving the planet rests mainly on lies. Thus, last week Glenn Beck — who seems to be challenging Rush Limbaugh for the role of de facto leader of the G.O.P. — informed his audience of a “buried” Obama administration study showing that Waxman-Markey would actually cost the average family $1,787 per year. Needless to say, no such study exists. But we shouldn’t be too hard on Mr. Beck. Similar — and similarly false — claims about the cost of Waxman-Markey have been circulated by many supposed experts. A year ago I would have been shocked by this behavior. But as we’ve already seen in the health care debate, the polarization of our political discourse has forced self-proclaimed “centrists” to choose sides — and many of them have apparently decided that partisan opposition to President Obama trumps any concerns about intellectual honesty. So here’s the bottom line: The claim that climate legislation will kill the economy deserves the same disdain as the claim that global warming is a hoax. The truth about the economics of climate change is that it’s relatively easy being green. In Areas Fueled by Coal, Climate Bill Sends Chill Dilip Vishwanat for The New York Times LaVerne McCoy weatherized her home near St. Louis in the hope of lowering her electricity bill. By FELICITY BARRINGER Published: April 8, 2009 ST. LOUIS — Chatting with a visitor about energy issues in the back of the Greater Mount Carmel Baptist Church here, a group of women exploded in laughter at the idea that their electric rates were among the lowest in the nation. Dilip Vishwanat for The New York Times One of the 21 coal-fired power plants in Missouri that emit more than 75 million tons of carbon dioxide annually and generate 80 percent of the state’s electricity. “We can barely afford what we have now,” said Renee Daniels-Hanner, 48, an office manager who lives with her husband, a postal employee, and their teenage daughter in a three-bedroom brick home in the city’s Baden neighborhood. The house, built in 1953, has central air-conditioning to ward off the heat and humidity of Mississippi River summers, a double-door refrigerator, a washer and dryer, six televisions, three computers and an iron (“We iron all the time,” Ms. Daniels-Hanner said). The family’s monthly electric bill averages $160 in winter and $250 in summer. From the wheat fields of the north-central region to Kansas City’s necklace of industrial parks to the brick street fronts of St. Louis, Missouri’s reliance on cheap electricity is deeply ingrained. But few pay attention to the origin of their little-noticed savings: 21 coal-fired power plants that emit more than 75 million tons of carbon dioxide annually and generate 80 percent of Missouri’s electricity. Even residents who endorse wind and solar energy have grown accustomed to the benefits of state policies that favor coal by putting a premium on low-cost electricity. So the idea of federal climate legislation that could increase electricity bills by putting a price on emissions of heat-trapping gases like carbon dioxide is unsettling. For Missourians, said Robert Clayton, chairman of the state’s Public Service Commission, “the consequence of using more power hasn’t been great.” Missouri is hardly alone. Nebraska, Indiana and Iowa are also states where coal turns on most of the lights. That is why, even before Representatives Henry A. Waxman of California and Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts, both Democrats, proposed legislation that would put a price on carbon-dioxide emissions, Senate and House Democrats from coal-using states began to push back. They are concerned that the new costs would get passed on to consumers, to Ms. DanielsHanner, to farmers from rural Missouri and to employers like the energy-hungry Noranda aluminum plant in New Madrid in the southeast of the state, which has 1,000 workers. And they worry that in an already wounded economy, increased costs could turn one of the relatively few economic blessings into a blight. Here in Missouri, economic incentives built into the state’s laws, history and habits encourage burning as much coal as possible. Peabody Energy started as a local business a century ago and now promotes itself as the world’s leading coal merchant. Trainloads of Wyoming coal cross Missouri daily. The cars arrive at places like Meramec, a 56-year-old, 850-megawatt power plant in south St. Louis County. The cost of building the sprawling plant has long since been paid off by its owner, AmerenUE, an investor-owned utility. Because Meramec generates electricity from cheap fuel, it produces cheap power. And because Meramec’s operational costs are low and most equipment-replacement costs have been recouped, AmerenUE often underbids competitors in selling excess electricity out of state. These profits give Missouri consumers an extra discount. From 1987 to 2007, AmerenUE and its predecessor, Union Electric, did not raise electric rates, while power production rose about 65 percent. Estimates of the effects of the proposed federal climate legislation on electric rates vary. The central thrust of the Waxman-Markey bill is to make carbon-dioxide emissions expensive by capping them and creating allowances that utilities must acquire to function. In Washington, the measure is seen as a starting point and has little Republican support, which would make the backing of coal-state Democrats like Senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri critical. Jaime Haro, AmerenUE’s director of asset management and trading, said his company paid $30 to produce a megawatt-hour of electricity. The coal burned emits roughly a ton of carbon dioxide. If federal legislation effectively prices emissions at $30 a ton — estimates have varied from $20 to $115 — “my costs could double,” Mr. Haro said. Those costs probably would be passed on to customers. For now, Missouri ranks among the lowest five states in retail electricity rates — about 6.3 cents per kilowatt hour, compared with a national average of 8.9 cents. Ms. Daniels-Hanner and LaVerne McCoy find that surprising. Ms. McCoy, who works for a community-based group, ADE Consulting Services, has spent $4,000 weatherizing her split-level home in Richmond Heights, just west of St. Louis. Her bills still average $320 monthly. About 130 miles to the northwest, Wendi Wood, a teacher, and her husband, Lee Wood, a fourth-generation farmer, live near the small town of Clarence with their three teenagers. Their six-bedroom house is four years old, and they, too, have many appliances, including seven televisions. Electricity costs them about $280 in winter, $360 in summer. After the fall harvest, they dry grain in a silo; then the bills run $600 a month. “Electricity is a major factor in what we can afford,” Ms. Wood said. She wants Washington to fight climate change, but said, “Don’t hurt the rural farmer and rural America to do it.” The state is taking some steps to reduce its dependence on coal, like legislation pending in the General Assembly to give financial incentives for conservation. In November, voters approved expanding renewable-energy options. State utilities have varied plans. AmerenUE talks of building a companion to its nuclear power plant. Kansas City Power & Light is buying more wind power to offset emissions from a coal plant under construction. Springfield’s municipal utility is experimenting with underground storage of carbon dioxide. Associated Electrical Cooperative Inc. offers energy-saving light bulbs to its 800,000 rural customers and subsidizes home energy audits. “Ultimately, there’s going to have to be a re-evaluation of Missouri’s future,” Mr. Clayton said. Like Ms. Wood, Ms. Daniels-Hanner and Ms. McCoy worry about the effects of climate change. “We want to help our grandchildren,” Ms. McCoy said. “My problem is that the brunt of the improvement is going to be put on the backs of those who can’t afford it.” Op-Ed Columnist Betraying the Planet By PAUL KRUGMAN Published: June 28, 2009 So the House passed the Waxman-Markey climate-change bill. In political terms, it was a remarkable achievement. But 212 representatives voted no. A handful of these no votes came from representatives who considered the bill too weak, but most rejected the bill because they rejected the whole notion that we have to do something about greenhouse gases. And as I watched the deniers make their arguments, I couldn’t help thinking that I was watching a form of treason — treason against the planet. To fully appreciate the irresponsibility and immorality of climate-change denial, you need to know about the grim turn taken by the latest climate research. The fact is that the planet is changing faster than even pessimists expected: ice caps are shrinking, arid zones spreading, at a terrifying rate. And according to a number of recent studies, catastrophe — a rise in temperature so large as to be almost unthinkable — can no longer be considered a mere possibility. It is, instead, the most likely outcome if we continue along our present course. Thus researchers at M.I.T., who were previously predicting a temperature rise of a little more than 4 degrees by the end of this century, are now predicting a rise of more than 9 degrees. Why? Global greenhouse gas emissions are rising faster than expected; some mitigating factors, like absorption of carbon dioxide by the oceans, are turning out to be weaker than hoped; and there’s growing evidence that climate change is self-reinforcing — that, for example, rising temperatures will cause some arctic tundra to defrost, releasing even more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Temperature increases on the scale predicted by the M.I.T. researchers and others would create huge disruptions in our lives and our economy. As a recent authoritative U.S. government report points out, by the end of this century New Hampshire may well have the climate of North Carolina today, Illinois may have the climate of East Texas, and across the country extreme, deadly heat waves — the kind that traditionally occur only once in a generation — may become annual or biannual events. In other words, we’re facing a clear and present danger to our way of life, perhaps even to civilization itself. How can anyone justify failing to act? Well, sometimes even the most authoritative analyses get things wrong. And if dissenting opinion-makers and politicians based their dissent on hard work and hard thinking — if they had carefully studied the issue, consulted with experts and concluded that the overwhelming scientific consensus was misguided — they could at least claim to be acting responsibly. But if you watched the debate on Friday, you didn’t see people who’ve thought hard about a crucial issue, and are trying to do the right thing. What you saw, instead, were people who show no sign of being interested in the truth. They don’t like the political and policy implications of climate change, so they’ve decided not to believe in it — and they’ll grab any argument, no matter how disreputable, that feeds their denial. Indeed, if there was a defining moment in Friday’s debate, it was the declaration by Representative Paul Broun of Georgia that climate change is nothing but a “hoax” that has been “perpetrated out of the scientific community.” I’d call this a crazy conspiracy theory, but doing so would actually be unfair to crazy conspiracy theorists. After all, to believe that global warming is a hoax you have to believe in a vast cabal consisting of thousands of scientists — a cabal so powerful that it has managed to create false records on everything from global temperatures to Arctic sea ice. Yet Mr. Broun’s declaration was met with applause. Given this contempt for hard science, I’m almost reluctant to mention the deniers’ dishonesty on matters economic. But in addition to rejecting climate science, the opponents of the climate bill made a point of misrepresenting the results of studies of the bill’s economic impact, which all suggest that the cost will be relatively low. Still, is it fair to call climate denial a form of treason? Isn’t it politics as usual? Yes, it is — and that’s why it’s unforgivable. Do you remember the days when Bush administration officials claimed that terrorism posed an “existential threat” to America, a threat in whose face normal rules no longer applied? That was hyperbole — but the existential threat from climate change is all too real. Yet the deniers are choosing, willfully, to ignore that threat, placing future generations of Americans in grave danger, simply because it’s in their political interest to pretend that there’s nothing to worry about. If that’s not betrayal, I don’t know what is. An Affordable Salvation By PAUL KRUGMAN Published: April 30, 2009 The 2008 election ended the reign of junk science in our nation’s capital, and the chances of meaningful action on climate change, probably through a cap-and-trade system on emissions, have risen sharply. But the opponents of action claim that limiting emissions would have devastating effects on the U.S. economy. So it’s important to understand that just as denials that climate change is happening are junk science, predictions of economic disaster if we try to do anything about climate change are junk economics. Yes, limiting emissions would have its costs. As a card-carrying economist, I cringe when “green economy” enthusiasts insist that protecting the environment would be all gain, no pain. But the best available estimates suggest that the costs of an emissions-limitation program would be modest, as long as it’s implemented gradually. And committing ourselves now might actually help the economy recover from its current slump. Let’s talk first about those costs. A cap-and-trade system would raise the price of anything that, directly or indirectly, leads to the burning of fossil fuels. Electricity, in particular, would become more expensive, since so much generation takes place in coal-fired plants. Electric utilities could reduce their need to purchase permits by limiting their emissions of carbon dioxide — and the whole point of cap-and-trade is, of course, to give them an incentive to do just that. But the steps they would take to limit emissions, such as shifting to other energy sources or capturing and sequestering much of the carbon dioxide they emit, would without question raise their costs. If emission permits were auctioned off — as they should be — the revenue thus raised could be used to give consumers rebates or reduce other taxes, partially offsetting the higher prices. But the offset wouldn’t be complete. Consumers would end up poorer than they would have been without a climate-change policy. But how much poorer? Not much, say careful researchers, like those at the Environmental Protection Agency or the Emissions Prediction and Policy Analysis Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Even with stringent limits, says the M.I.T. group, Americans would consume only 2 percent less in 2050 than they would have in the absence of emission limits. That would still leave room for a large rise in the standard of living, shaving only one-twentieth of a percentage point off the average annual growth rate. To be sure, there are many who insist that the costs would be much higher. Strange to say, however, such assertions nearly always come from people who claim to believe that free-market economies are wonderfully flexible and innovative, that they can easily transcend any constraints imposed by the world’s limited resources of crude oil, arable land or fresh water. So why don’t they think the economy can cope with limits on greenhouse gas emissions? Under cap-and-trade, emission rights would just be another scarce resource, no different in economic terms from the supply of arable land. Needless to say, people like Newt Gingrich, who says that cap-and-trade would “punish the American people,” aren’t thinking that way. They’re just thinking “capitalism good, government bad.” But if you really believe in the magic of the marketplace, you should also believe that the economy can handle emission limits just fine. So we can afford a strong climate change policy. And committing ourselves to such a policy might actually help us in our current economic predicament. Right now, the biggest problem facing our economy is plunging business investment. Businesses see no reason to invest, since they’re awash in excess capacity, thanks to the housing bust and weak consumer demand. But suppose that Congress were to mandate gradually tightening emission limits, starting two or three years from now. This would have no immediate effect on prices. It would, however, create major incentives for new investment — investment in low-emission power plants, in energy-efficient factories and more. To put it another way, a commitment to greenhouse gas reduction would, in the short-tomedium run, have the same economic effects as a major technological innovation: It would give businesses a reason to invest in new equipment and facilities even in the face of excess capacity. And given the current state of the economy, that’s just what the doctor ordered. This short-run economic boost isn’t the main reason to move on climate-change policy. The important thing is that the planet is in danger, and the longer we wait the worse it gets. But it is an extra reason to move quickly. So can we afford to save the planet? Yes, we can. And now would be a very good time to get started.