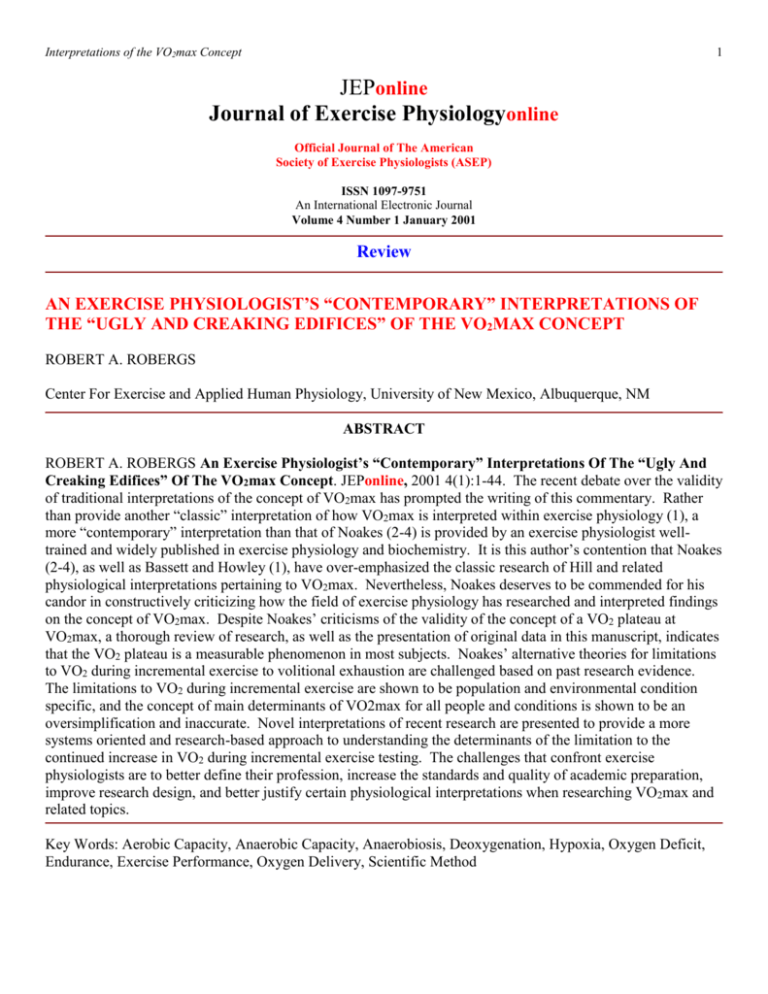

An Exercise Physiologist`s "Contemporary" Interpretations Of The

advertisement