BLADDER CANCER

advertisement

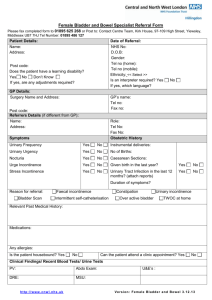

BLADDER CANCER Urothelial cancer is common. The majority are transitional cell carcinomas that arise from the specialised waterproof epithelium that lines the urinary tract. In men, this extends from the tips of the renal papillae to the navicular fossa; in women, to halfway along the urethra. Tumours can arise at any site in this epithelium and are often multifocal. The bladder is the most common site. Seventy percent of urothelial tumours are superficial at presentation; two-thirds will subsequently recur locally or elsewhere in urinary tract, and in 10-15%, the recurrence will be invasive. This potential instability of the urothelium is often described in terms of a "field change". Urothelial cancer: is uncommon before 50 years of age is most frequent in incidence at 65 years of age is more common in males by a factor of 3:1 in adults aged 15+ years in England and Wales in 1992 - there were 12,008 cases and the number per annum per 2000 population was 0.47 (1) 95% affect the bladder; 5% affect the upper tracts in 90% of cases, presentation is with macroscopic haematuria (1) 5-10% of patients present with microscopic haematuria is four times as common as renal adenocarcinoma has a 20 times more common incidence in paraplegics is common in industrialised countries is uncommon in the developing world except in bilharzial areas Note that both microscopic and macroscopic haematuria, when caused by a urothelial cancer are intermittent. Therefore repeat urine testing can be negative for haematuria in the presence of a tumour (1). Aetiology: No single causative factor is identifiable in the majority of cases. In others, there may be an association with: cigarette smoking - by itself, is associated with a 2-fold increased risk. Thought to be due to urinary excretion of inhaled carcinogens. Smoking may act synergistically with other risk factors. occupational exposure to carcinogens widely used in the rubber, cable, textile and printing industries. For example,beta naphthylamine, benzidine, 4-diphenylalinine, and auramine and magenta dyes. Such exposure can be proven in only a small proportion of patients. There may be a latent period of 15-20 years. The bladder is particularly vulnerable as it exposed to urine for longer than other parts of the urinary tract. drugs - e.g. phenacetin, aspirin, cyclophosphamide. fungal toxins in Balkan nephropathy endogenous carcinogens - e.g. nitrosamines, tryptophane metabolites (aminophenols) squamous cell carcinoma is associated with chronic irritation and squamous metaplasia due to bladder stones or schistosomiasis. The latter is the main cause of bladder cancer worldwide. adenocarcinoma may develop in peristent urachal remnants adenocarcinoma or squamous carcinoma may be associated with bladder exstrophy Pathology: Classification: transitional cell carcinoma - 90% squamous carcinoma - 5-8% adenocarcinoma - 1-2% sarcoma - rare Distribution: calyces and renal pelvis - 9% ureter - 1% bladder - 90%: o posterior and lateral walls - 70% o trigone and bladder neck - 20% o vault - 10% o diverticulum - 1-5% urethra - less than 1% Carcinoma in situ is a potentially aggressive tumour that may occur anywhere in the urinary tract. Malignant change is confined to the bladder mucosa. Tumours in the upper urinary tract often present late. Spread: The spread of urothelial cancer is via the following routes: direct invasion - through the bladder wall and perivesical fat, and into adjacent structures such as the prostate and uterus lymphatics - there are few lymphatics immediately under the bladder mucosa but they are abundant in its muscle wall. Bladder cancer that penetrates the muscle quickly reaches pelvic lymph nodes. haematogenous distant spread - to liver, lungs, bone, and brain Features: Features of the primary urothelial tumour may include: painless total haematuria - the classic presentation of bladder cancer, occurring in 7090% of cases; 20% of patients with haematuria are found later to have a urinary tract tumour. In 10% of patients over 45 years with microscopic haematuria, tumour is responsible. ureteric colic - may occur due to clots from an upper tract lesion. Long, stringy clots may be seen in the urine. Heavy bleeding may cause obstruction. sterile pyuria, i.e. pus cells without urinary infection. May also occur with calculi, tuberculosis, partially treated infection. malignant cystitis - frequency, dysuria and urgency. A common presentation of carcinoma in situ. Haematuria may be absent. urinary tract infection in a man, or recurrent UTI in a woman palpable suprapubic mass Secondary features may include: bladder outflow obstruction - involvement of bladder neck ureteric obstruction - involvement of ureteric orifices. Causes renal pain and hydronephrosis. Uraemia may occur in bilateral occlusion, but is rare. perineal and sacral pain - extension of tumour outside the bladder enlarged pelvic lymph nodes - lymphatic spread hepatomegaly - liver metastases bone pain - bony metastases General effects of malignancy: weight loss, anaemia, pyrexia of unknown origin Investigations: The investigations of choice in any patient with haematuria are: urinalysis - culture for bacteria, microscopy to confirm presence of red blood cells, and cytology for malignant cells. Urine cytology enables diagnosis and grading of the tumour in 60% of cases. intravenous urography - upper urinary tract tumours usually appear as filling defects in the renal pelvis or ureters. Rarely, the renal outline may be distorted. A bladder tumour may cause ureteric obstruction. An IVU will usually demonstrate a renal adenocarcinoma causing haematuria. ultrasound cystoscopy and bimanual examination under anaesthesia - critical for staging and subsequent management Other useful investigations are: full blood count, urea and electrolytes, creatinine chest x-ray abdominal CT - especially if radical surgery contemplated Staging: Grading and staging is made at cystoscopy. Any visible tumour is resected. This is sent for histology to grade the tumour. The bladder is then washed out. A bimanual examination is performed to determine the clinical stage. A further deep biopsy is taken. This is sent for histology to determine the pathological stage. Grading is either: G1 - well differentiated G2 - moderately differentiated G3 - poorly differentiated Staging is by the TNM system. A T prefix denotes the stage as assessed clinically. A p prefix is added when the clinical findings are supported by pathological analysis. Pathological stages pT3 and pT4 can only be made on bladder specimens after total or partial cystectomy. Upper urinary tract tumours can only be staged from surgically excised specimens. Nodal and metastatic spread is assessed only when radiotherapy or radical surgery is contemplated. Treatment: Superficial: Superficial tumours of the bladder, i.e. pTa and pT1, are mainly treated by transurethral resection. Intravesical cytotoxic chemotherapy using agents such as thiotepa, mitomycin, doxorubicin, and epirubicin, may be given as adjuvant therapy, as they reduce the multiplicity and frequency of recurrence. If the superficial lesions are too numerous to be resected, alternative methods include: intravesical cytotoxic chemotherapy alone Helmstein balloon inflation - causes pressure necrosis of tumour Intravesical BCG immunotherapy may be required for carcinoma in situ and pT1G3 cancer. In all cases, regular endoscopic follow up is essential. T2 disease: T2 tumours account for about 15% of bladder tumours. When there is no palpable mass in the bladder wall after staging, it may be assumed that all viable tumour has been removed. Follow-up as for superficial disease is indicated. When thickening is palpable after staging, treatment is by external radiotherapy or less commonly in the UK, by cystectomy. Life-long endoscopic follow-up is indicated. If tumour is present in the bladder 6 months after radiotherapy, or recurs, treatment by total cystectomy with urinary diversion is indicated. T3 disease: External radiotherapy is the treatment of choice for T3 bladder cancer as complete resection carries the risk of bladder perforation. Recurrence after radiotherapy, or radiotherapy complicated by bleeding, contraction, incontinence or fistulae, is an indication for salvage cystectomy, i.e. total cystectomy removal of lower ureters, bladder, urethra, and either prostate or gynaecological organs - with urinary diversion. T4 disease: Palliative radiotherapy only can be offered to control pain and haematuria with T4 staged bladder cancer. Prognosis: 5-year survival carcinoma in situ 30-40% pTa 90-95% pT1 40-75% pT2 55% pT3 25% pT4 5-10% Follow up: Life-long follow-up is indicated for all bladder cancers other than stage T4, and for all upper tract lesions. Check cystoscopy should be performed every three months, and then, if the patient remains tumour free, annually. After several years tumour free, cystoscopy may be replaced by annual urine cytology