- D

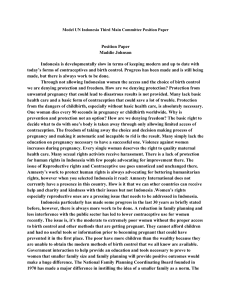

advertisement