CAUSAL ANALYSIS FORMAT GUIDELINES:

advertisement

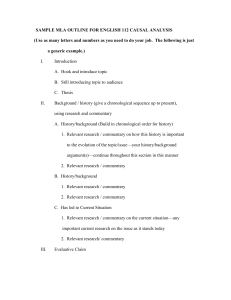

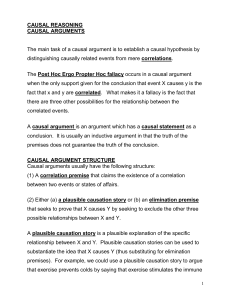

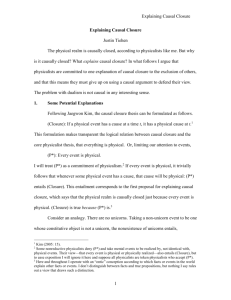

CAUSAL ANALYSIS GUIDELINES: According to John J. Ruskiewicz and Jay T. Dolmage, “We all analyze and explain things daily. Someone asks, ‘Why?’ We reply, ‘Because . . .’ and then offer reasons and rationales” (138). This type of thinking is at the core of the causal analysis. You will write a causal analysis which explores, through carefully examined research and logical analysis, certain causes or factors which contribute to an issue or problematic situation within a professional field which interests you in a serious way. Are you considering a career in criminal justice or law enforcement, education, medicine, human resources, child development, science, business, graphic design, horticulture/agriculture, veterinary medicine, industrial science, etc? This project will allow you to do research and learn more about your chosen or potential career path and the conversations surrounding that career, while allowing you to grow as a writer, critical thinker, and steward of information. Your causal analysis project will be structured and organized using the “classical system,” based on a structure used by Greek and Roman rhetors 2,000 years ago, which is still utilized in arguments and speeches today. You will acknowledge, through breadth and depth, the complexities of causal arguments. Your causal analysis may explore more than one type of cause, such as necessary causes, sufficient causes, precipitating causes, proximate causes, remote causes, reciprocal causes, contributing factors, and chains of causes, as outlined in our course text in the chapter devoted to Causal Analyses. Your project will also reflect significant critical thinking skills. In addition to the actual causal analysis essay, you will be asked to create a formal outline of your essay as well as an annotated bibliography. These process elements will help you organize and focus your ideas and research in a beneficial way. The following is an organizational structure which outlines the chronology and content of your Causal Analysis: I. II. Introduction: In one (or at the most two) paragraph(s) introduce your topic. Give a brief overview of your topic and argument in a few sentences. Remember to include a thesis statement which specifically sets out what you are proving to be true regarding the causes of the negative situation. This is your enthymeme: your evaluative claim and your causal claim. It should be specific, logical, and clear. History/Background to Current Situation: This section should take as much space as needed—a few to several paragraphs. Discuss the significant and relevant history of your topic up to the current situation and how it came to be. Use research as needed to give precise and accurate background for context in making your later causal argument. Comment on your research as well, so that you don’t lose your voice. As you explore other points of view, your own point of view will evolve in significant ways. III. IV. Evaluative Claim: Once you have given a brief history/background of the current situation, evaluate the situation as it is at present. Again, use research as appropriate to support your judgments. While this section of your essay could run anywhere from one to three paragraphs, typically one paragraph is the norm, as you are basically passing judgment on the situation, arguing evaluatively. This is an argument of pathos and logos, predominantly. Causal Argument: This is the longest portion of your essay, the “meat,” the heart of your work. Once you have detailed the history/background to current situation and evaluated the current situation, you are ready to present your causal analysis. Demonstrate a link between the current situation and the causes for its negative condition. Of course, you will use current significant and relevant research to support your causal claim, and you will want to find the most dominant and pervasive logical causes, utilizing research, for the current situation as possible. These will connect forward as well to your proposal. Remember to use specific supporting detail/examples, and to analyze all of your research causally, thoroughly, and with clarity. A NOTE: SECTIONS THREE AND FOUR ABOVE ARE INTERCHANGEABLE. IN OTHER WORDS, IF YOU FEEL YOU CAN PRESENT A BETTER ARGUMENT BY SHOWING CAUSES FIRST AND THEN EVALUATING THE CURRENT SITUATION, THAT CAN WORK JUST AS WELL AS THE ORDER OUTLINED ABOVE. I WILL LEAVE IT UP TO YOU AS THE WRITER TO ESTABLISH WHICH ORDER WORKS MOST EFFECTIVELY. V. VI. Counterargument/Conditions of Rebuttal and Rebuttal: There will be those who disagree with you so you will want to acknowledge their points of view. What are their assumptions about this topic? What questions do they raise for consideration? Acknowledging other points of view gives your essay credibility and shows that you have been fair and broad in your inquiry and presentation. (You will need at least one credible source to represent at least one counterargument.) Then explain how you have considered this counterargument, but still find your own analysis to be more logical and accurate; this is your rebuttal. Conclusion: Summarize the meaningful conclusions you have drawn clearly and precisely, remembering to resummarize your thesis. Give your specific proposal here as well. This will become your transition paragraph between the causal analysis and the proposal, so you must state your proposal precisely to pave the way for the proposal argument in full to come. Keep in mind the critical thinking student learning outcomes: Pursue the best information. Engage in broad and deep inquiry Analyze different points of view Examine and challenge your own underlying assumptions as you undergo this exciting journey in scholarship. Please also ponder these questions as you progress through your research and project work: About yourself: What assumptions did you have about this topic coming into the project? Have some of those assumptions been challenged? Have some been validated? What questions do you still have about your issue? What questions have you been able to answer through your inquiry? About your audience: What questions does your audience have about your topic? What points of view do they represent? What information do you want to provide to help answer those questions? How can you address a diverse audience so that its members will be moved to see your own point of view as significant and worth consideration? How has pursuing the best information in a fair and honest, ethical, and logical manner allowed you to show respect for your audience as well as yourself as a thinker? Good luck, scholars!