police power regulation of intangible commercial property

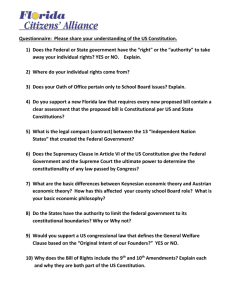

advertisement