Innovations to address postpartum haemorrhage in low

advertisement

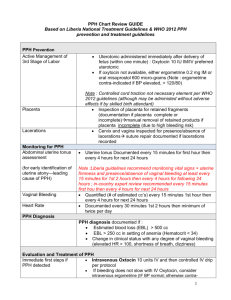

Innovative interventions to address postpartum haemorrhage in low-income countries Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a common obstetric complication defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as blood loss of 500 ml or more 1. WHO states that the loss of 500 ml of blood should be considered an alert, after which the health of the woman may be endangered1. Haemorrhage, including PPH, is a leading cause of death in developing countries, accounting for approximately one-third of all direct obstetric deaths in Africa (33.9%) and Asia (30.8%)2. The Millennium Development Goal 5 of reducing the maternal mortality ratio by 75% by 2015 will not be achieved unless the prevention and treatment of PPH in low-resource areas is prioritised 3. This table provides a summary of some of the innovative interventions used to manage PPH in low-income countries. It highlights the advantages and disadvantages of each intervention and critically assesses the evidence base available. These interventions include oral misoprostol, a non-pneumatic anti-shock garment, oxytocin in prefilled Uniject™ injection devices, and a hydrostatic intrauterine balloon tamponade. These innovations add to the range of interventions available to help prevent, manage and/or treat PPH and improve health outcomes. These include the administration of uteronics (e.g. oxytocin) or delayed cord clamping (for PPH prevention), and intravenous uterine artery embolization or intravenous oxytocin or ergometrine (for treatment of PPH)4. Three key messages need to be considered in order to maximize the effectiveness of interventions to address PPH. Firstly, preventing and treating PPH should take place within a comprehensive package of interventions from the “household to hospital continuum of care”4(p1). Secondly, even the most sophisticated PPH interventions can only prevent maternal deaths if they are delivered within a functional health system. Finally, blood transfusion is one of the most reliable strategies to respond to severe bleeding as a result of PPH, particularly in the absence of other interventions. Blood transfusions are an essential part of a comprehensive package of life saving interventions used to manage obstetric complications5. An estimated 15% of all births are expected to result in direct obstetric complications5, thus making it even more important to ensure that safe blood transfusions are available. 1 Innovation Oral Misoprostol [6] Use Prevent and treat PPH Advantage For PPH prevention, the WHO recommends to use oral misoprostol (600 µg) in settings where oxytocin is not available. Alternative to oxytocin in settings where this is unavailable. For treatment of PPH, the WHO recommends using oral misoprostol (800 µg) as a second line treatment if oxytocin is not effective. Non-pneumatic anti-shock garment (NASG) [7-19] Management of PPH and Shock The NASG reverses shock by compressing the lower-body vessels, decreasing the container size of the body, so circulating blood is directed mainly to the core organs. It also compresses the diameter of pelvic blood vessels, thus Disadvantage Simple technology that can be learned easily. Does not take much shelf space, is easy to clean, and is reusable. Device to stabilise women with shock until definitive treatments can be given – very good for referrals. Evidence There are concerns regarding the community-level distribution of misoprostol and the potential for serious consequences if administered before birth. It is therefore advised to train persons administering misoprostol and monitor community distribution interventions with scientifically sound methods and appropriate indicators. Some members of the Guideline Development Group (GDG) felt that there might be a risk of hyperpyrexia associated to the dosage of 800 μg dose of misoprostol for the treatment of PPH. Unlikely to cause harm. Needs financial input. Moderate quality evidence for prevention according to the GDG. Low-quality evidence for treatment according to the GDG. A definitive trial of the NASG for use prior to transport from lower-level facilities to tertiary facilities is currently underway in Zambia and Zimbabwe. This trial will address the question of whether early application of the NASG at the satellite health facility level before transport to a referral hospital will decrease maternal mortality and morbidity. 2 decreasing blood flow to the uterus. Oxytocin in prefilled Uniject™ injection devices [20-26] Used to prevent PPH Uniject™ injection device is an auto-disable, “all-in-one” injection system prefilled with a single dose of oxytocin 10 IU. Hydrostatic intrauterine balloon tamponade Management of PPH A hydrostatic intrauterine balloon tamponade is a ‘balloon’ usually made of The injection ready format reduces wastage, simplifies logistics. Allows use both by lay health personnel who do not normally administer injections and in areas with limited health infrastructure The time temperature indicator ensures that even lay users are able to easily assess if a specific dose is still potent. Oxytocin in Uniject TM has been found to be well tolerated and easy to use and has a high level of acceptability among providers. Low cost and ready availability. Very effective to arrest bleeding. Also used to test if the bleeding is uterine or from another Would replace the current use of syringe and needle, which is not very different to the innovation. The available evidence indicates that the NASG substantially decreases blood loss, but there is no evidence that its application will reduce extreme adverse outcomes. It is also not known if possible side effects associated with NASG use might outweigh potential benefits. No evidence that NASG contributes to maternal mortality reduction. The main limitation of the findings is that none of the evidence derives from either randomised control trials or even a study with a control group. Such a design cannot exclude the possibility that secular trends or the effect of other simultaneous interventions could be alternative explanations of the findings. Furthermore, the small sample size of studies means that chance cannot be excluded as a likely explanation. No evidence that Uniject™ contributes to maternal mortality reduction. More research is needed. Complication rates are reported to be low. More research is needed to verify this. No randomised controlled studies of hydrostatic intrauterine balloon tamponade have been conducted leaving doubt on the effectiveness of these devices. Additionally, there is no 3 [27-37] synthetic rubber balloon catheters that is inserted into the uterus, at onset of a PPH. This device is attached to a syringe and filled with sufficient saline solution, to exert enough counterpressure to stop bleeding. source way to be certain whether a woman who had a uterine balloon placed would have had a different outcome had the balloon not been placed. Despite the many open questions, current research does suggest that the balloon tamponade is effective and FIGO recommends that it should become well integrated in the treatment of PPH at all levels of the health system. No evidence that balloon tamponades contribute to maternal mortality reduction. 4 References: 1. WHO. WHO guidelines for the management of postpartum haemorrhage and retained placenta. Geneva: WHO, 2009. 2. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006 Apr 1;367(9516):1066-74. PubMed PMID: 16581405. Epub 2006/04/04. eng. 3. UN. Millennium Development Goals 2012. Available from: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/. 4. WHO. WHO recommendations on prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: Highlights and Key Messages from New 2012 Global Recommendations. Geneva: WHO, 2012. http://www.mchip.net/sites/default/files/PPH%20Briefer%20(General).pdf. 5.WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF and AMDD. A handbook on monitoring emergency obstetric care. Geneva: WHO, 2009 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241547734_eng.pdf 6. WHO. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. WHO: Geneva, 2012. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/9789241548502/en/index.html 7. Lester F, Stenson A, Meyer C, Morris J, Vargas J, Miller S. Impact of the Non-pneumatic Antishock Garment on pelvic blood flow in healthy postpartum women. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2011 May;204(5):409 e1-5. PubMed PMID: 21439543. 8. Kausar F, Morris JL, Fathalla M, Ojengbede O, Fabamwo A, Mourad-Youssif M, et al. Nurses in low resource settings save mothers' lives with non-pneumatic anti-shock garment. MCN The American journal of maternal child nursing. 2012 Sep;37(5):308-16. PubMed PMID: 22895203. 9. Miller S, Turan JM, Dau K, Fathalla M, Mourad M, Sutherland T, et al. Use of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment (NASG) to reduce blood loss and time to recovery from shock for women with obstetric haemorrhage in Egypt. Global public health. 2007;2(2):110-24. PubMed PMID: 19280394. 10. Hensleigh PA. Anti-shock garment provides resuscitation and haemostasis for obstetric haemorrhage. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2002 Dec;109(12):1377-84. PubMed PMID: 12504974. 11. Brees C, Hensleigh PA, Miller S, Pelligra R. A non-inflatable anti-shock garment for obstetric hemorrhage. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2004 Nov;87(2):119-24. PubMed PMID: 15491555. 12. Miller S, Hamza S, Bray EH, Lester F, Nada K, Gibson R, et al. First aid for obstetric haemorrhage: the pilot study of the non-pneumatic antishock garment in Egypt. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2006 Apr;113(4):424-9. PubMed PMID: 16553654. 13. Miller S, Ojengbede O, Turan JM, Morhason-Bello IO, Martin HB, Nsima D. A comparative study of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment for the treatment of obstetric hemorrhage in Nigeria. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2009 Nov;107(2):121-5. PubMed PMID: 19628207. 5 14. Mourad-Youssif M, Ojengbede OA, Meyer CD, Fathalla M, Morhason-Bello IO, Galadanci H, et al. Can the Non-pneumatic Anti-Shock Garment (NASG) reduce adverse maternal outcomes from postpartum hemorrhage? Evidence from Egypt and Nigeria. Reproductive health. 2010;7:24. PubMed PMID: 20809942. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2942803. 15. Ojengbede OA, Morhason-Bello IO, Galadanci H, Meyer C, Nsima D, Camlin C, et al. Assessing the role of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment in reducing mortality from postpartum hemorrhage in Nigeria. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 2011;71(1):66-72. PubMed PMID: 21160197. 16. Miller S, Fathalla MM, Youssif MM, Turan J, Camlin C, Al-Hussaini TK, et al. A comparative study of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment for the treatment of obstetric hemorrhage in Egypt. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2010 Apr;109(1):20-4. PubMed PMID: 20096836. 17. Turan J, Ojengbede O, Fathalla M, Mourad-Youssif M, Morhason-Bello IO, Nsima D, et al. Positive effects of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment on delays in accessing care for postpartum and postabortion hemorrhage in Egypt and Nigeria. Journal of women's health. 2011 Jan;20(1):91-8. PubMed PMID: 21190486. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3052289. 18. Miller S. Non-Pneumatic Anti-Shock Garment for Obstetrical Hemorrhage: Zambia and Zimbabwe (NASG) 2012. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00488462. 19. RTI International. Anti-shock garments to reverse hypovolemic shock and reduce obstetric hemorrhage 2011. Available from: www.mnhtech.org/uploads/Anti-Shock-Garments.pdf 20. PATH. Resources for oxytocin in the Uniject™ injection system 2012. Available from: http://www.path.org/projects/uniject-oxytocinresources.php. 21. WHO. Stability of injectable oxytocics in tropical climates. Geneva: WHO, 1993. 22. Tsu VD, Sutanto A, Vaidya K, Coffey P, Widjaya A. Oxytocin in prefilled Uniject injection devices for managing third-stage labor in Indonesia. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2003 Oct;83(1):103-11. PubMed PMID: 14511884. 23. Strand RT, Da Silva F, Jangsten E, Bergström S. Postpartum hemorrhage: a prospective, comparative study in Angola using a new disposable device for oxytocin administration. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2005;84(3):260-5. 24. Tsu VD, Luu HT, Mai TT. Does a novel prefilled injection device make postpartum oxytocin easier to administer? Results from midwives in Vietnam. Midwifery. 2009 08/;25(4):461-5. 25. Althabe F, Mazzoni A, Cafferata ML, Gibbons L, Karolinski A, Armbruster D, et al. Using Uniject to increase the use of prophylactic oxytocin for management of the third stage of labor in Latin America. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2011 Aug;114(2):184-9. PubMed PMID: 21693378. 6 26. Stanton C, Newton S, Mullany L, Cofie P, Agyemang C, Adiibokah E, et al. Impact on postpartum hemorrhage of prophylactic administration of oxytocin 10IU via UnijectTM by peripheral health care providers at home births: design of a community-based cluster-randomized trial. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2012;12(1):42. PubMed PMID: doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-42. 27. FIGO. PPH Guidelines 2012. Available from: http://www.figo.org/publications/PPH_Guidelines. 28. Manaktala U, Dubey C, Takkar A, Gupta S. Condom catheter balloon in management of massive nontraumatic postpartum haemorrhage during cesarean section. J Gynecol Surg. 2011;27:115-7. 29. Akhter S, Begum MR, Kabir Z, Rashid M, Laila TR, Zabeen F. Use of a condom to control massive postpartum hemorrhage. MedGenMed : Medscape general medicine. 2003 Sep 11;5(3):38. PubMed PMID: 14600674. 30. Ikechebelu JI, Obi RA, Joe-Ikechebelu NN. The control of postpartum haemorrhage with intrauterine Foley catheter. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005 Jan;25(1):70-2. PubMed PMID: 16147704. 31. Sheikh L, Zuberi NF, Riaz R, Rizvi JH. Massive primary postpartum haemorrhage: setting up standards of care. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2006 Jan;56(1):26-31. PubMed PMID: 16454132. 32. Bagga R, Jain V, Sharma S, Suri V. Postpartum hemorrhage in two women with impaired coagulation successfully managed with condom catheter tamponade. Indian journal of medical sciences. 2007 Mar;61(3):157-60. PubMed PMID: 17337818. 33. Airede LR, Nnadi DC. The use of the condom-catheter for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage - the Sokoto experience. Tropical doctor. 2008 Apr;38(2):84-6. PubMed PMID: 18453493. 34. Nahar N, Yusuf N, Ashraf F. Role of intrauterine balloon catheter in controlling massive PPH: experience in Rajshahi Medical College Hospital. The Orion Med J. 2009;2:682-3. 35. Thapa K, Malla B, Pandey S, Amatya S. Intrauterine condom tamponade in management of post partum haemorrhage. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2010 04/;8(1):19-22. 36. Rather SY, Qadir A, Parveen S, Jabeen F. Use of condom to control intractable PPH. JK Science. 2010;12:127-9. 37. Sheikh L, Najmi N, Khalid U, Saleem T. Evaluation of compliance and outcomes of a management protocol for massive postpartum hemorrhage at a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2011;11(1):28. PubMed PMID: doi:10.1186/1471-2393-1128. 7