Brochure Text - Kansas Humanities Council

advertisement

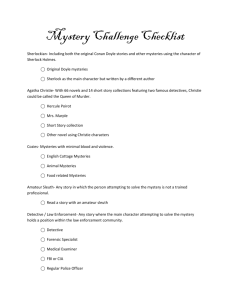

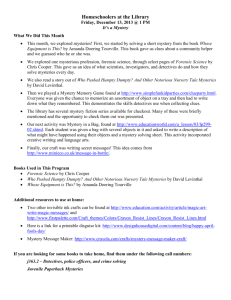

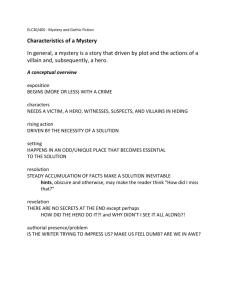

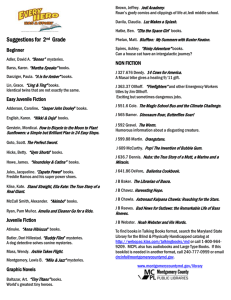

Talk About Literature in Kansas is a program for every Kansan who loves to read and discuss good books. For more information about TALK and other programs for libraries, museums, and non-profit groups, contact the Kansas Humanities Council 11112 SW 6th Ave., Suite 210 Topeka KS 66603-3895 785/357-0359 info@kansashumanities.org • www.kansashumanities.org Today’s Mysteries Since Sherlock Holmes was “born” more than a hundred years ago, mystery stories have become one of America’s most popular forms of fiction. Holmes’s creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, first put it all together by writing stories in which appealing and eccentric characters encounter and solve puzzles, thereby restoring order and justice. In mystery fiction’s inter-war Golden Age, writers such as Agatha Christie, Rex Stout, and Dorothy Sayers deepened but also continued Doyle’s original great formula. Thanks to them, such mysteries today give us not only plots to debate, writing to analyze, characterizations and motives to discuss, but also memorable pictures of a certain time and society. However, these pictures are almost always of a quite narrow, privileged, slice of society. Only at the end of the era did “mean streets” writers such as Raymond Chandler write about other kinds of lives, and about the flaws within the dominant order. Today, mysteries have exploded far beyond their Golden Age beginnings, and so give us a much broader view of the world and the many kinds of people and problems within it. Beyond the traditional “cozies” that continue Golden Age styles, mysteries now include spy thrillers, police procedurals, and psychological cliff-hangers. There are female as well as male private investigators out on the “mean streets.” Readers are now introduced to almost every possible culture and historic era. Although often called “Who-Dun-Its,” today’s mysteries are quite often instead “Why-Dun-Its,” exploring psychological motivation and the problems of modern society. But there are also strong continuities to the best features of past mysteries. The best mysteries now as then are compellingly written and strongly plotted, feature fascinating characters, and still raise crucial questions of justice, societal problems, and human motivation. These characteristics, both new and old, make for stimulating and meaningful humanities discussions. 2 Bootlegger’s Daughter by Margaret Maron (date unavailable) Margaret Maron has been writing quite successful mystery novels since 1981, when she published her first Sigrid Harald New York City police procedural. But, in the opinion of most critics, she really “found her voice” with the 1992 publication of her multiple-award-winning Bootlegger’s Daughter. In it Maron introduces Deborah Knott, North Carolina lawyer, candidate for judge, and bootlegger’s daughter. Talked into investigating an unsolved eighteen-year murder, Deborah delves into the messy past, campaigns at countless local political events, and fends off her huge family. Maron, herself a returned North Carolina native, brings alive all the complexities, richness, and humor of the modern woman’s New South. Maron’s Deborah Knott series has won her fans from all lovers of mysteries about strong women; her humorous, mainstream detective avoids the extremes of “mean streets” private detectives, but still confronts the many realities faced by independent women today. 261 pp. Reflex by Dick Francis (1920- ) Francis was champion jockey to England’s Queen Mother until advancing age and injuries brought his retirement in the late 1950s. He then turned to writing and in 1962 published his first mystery, Dead Cert. More than thirty books later, Francis is still going strong with his first-person tales of intrepid young men’s adventures. All of his heroes are connected in some way with racing; many are jockeys. In Reflex, jockey Philip Nore begins to suspect that a track photographer’s fatal accident was really murder, now will he become the next victim? It is vintage Francis, with a compelling plot, tight and effective writing, a likable main character and a fascinating setting. Fans call his books “cracking good reads.” 346 pp. Shroud for a Nightingale by P. D. James (1920- ) P. D. James is the pen name of Phyllis Dorothy James White, now Baroness James of Holland Park. James worked as a civil servant for many years to support her family after her husband returned mentally incapacitated from World War II. Eventually she began writing and in 1962 published Cover Her Face. By the time Shroud for a Nightingale was published in 1971, James was winning worldwide notice for the literary qualities of her writing, her acutely-observed characterizations and place descriptions, and her ability to convey atmospheres of menace and tension. In Shroud, Adam 3 Dalgliesh must untangle a series of murders within Nightingale House, a hospital nursing school. The resulting solution raises many questions about the nature of evil, personal responsibility, and justice. Fans call James’s books great literature. 287 pp. Talking God by Tony Hillerman (1925-2008) Although not a Navajo himself, Tony Hillerman has taught millions of Americans most of what they know about Navajo lands and culture. It all began with the 1970 publication of The Blessing Way, in which Hillerman introduced Joe Leaphorn of the Navajo Tribal Police. The 1989 Talking God features Leaphorn and Officer Jim Chee, also of the tribal police. Both Leaphorn and Chee tackle different aspects of a case which includes an anonymous corpse discovered on tribal lands and disputes over the Smithsonian Institution’s rights to Indian bones and other artifacts. At the same time, Chee is struggling to find a way to balance his love of ancient Navajo beliefs and ceremonies with modern-day demands. The story is a complex one which also offers readers glimpses of Navajo ceremonials and culture, and of reservation daily life. It should provide fertile grounds for discussing the collision of cultures within the American “melting pot,” as well as of the nature of both personal and institutional choices. Hillerman is an entertaining writer and an education in Navajo ways. 338 pp. Where Echoes Live by Marcia Muller (1944- ) Marcia Muller has been called the “founding mother” of female private-eye writing. While other writers in the genre are currently better known, Marcia Muller started the trend in 1977 with her Edwin of the Iron Shoes. In her 1991 Where Echoes Live, Muller’s main character, investigator Sharon McCone, travels to California’s desert-bound Tufa Lake. She is sent there by her employer, the San Francisco legal co-operative All Souls, to help environmentalists fight plans to develop an abandoned gold mine. Along with complex questions of environmentalism vs. commercial development, McCone confronts her own personal dilemmas with strength and humor. These include questions of how adult daughters relate to their mothers, and what sort of personal relationships a very independent, danger-loving woman wants and can build in her own life. Fans call Muller’s McCone not only the first, but the best and most readable of the “hard boiled” female private eyes. 358 pp. 4 Suggestions for Further Reading Swanson, Jean and Dean James. By a Woman’s Hand: A Guide to Mystery Fiction by Women. Waugh, Hillary. Hillary Waugh’s Guide to Mysteries & Mystery Writing. Winks, Robin W. Detective Fiction: A Collection of Critical Essays . Dick Francis fans will like: Mysteries by John D. MacDonald, Robert Parker, Rex Stout, and Ross Thomas. Tony Hillerman fans will like: Jean Hager (about Cherokees) and Dana Stabenow (native Alaskans). P. D. James fans will like: Elizabeth George, Ruth Rendell, and Dorothy L. Sayers. Margaret Maron fans will like: Sharyn McCrumb, Sarah Shankman, and Julie Smith’s Rebecca Schwartz stories. Marcia Muller fans will like: Janet Dawson, Sue Grafton, Sara Paretsky, and Julie Smith.